Biomineralization

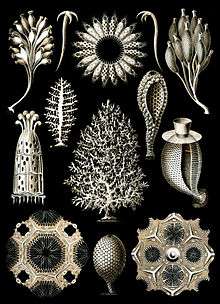

Biomineralization, or biomineralisation is the process by which living organisms produce minerals,[lower-alpha 1] often to harden or stiffen existing tissues. Such tissues are called mineralized tissues. It is an extremely widespread phenomenon; all six taxonomic kingdoms contain members that are able to form minerals, and over 60 different minerals have been identified in organisms.[2][3][4] Examples include silicates in algae and diatoms, carbonates in invertebrates, and calcium phosphates and carbonates in vertebrates. These minerals often form structural features such as sea shells and the bone in mammals and birds. Organisms have been producing mineralised skeletons for the past 550 million years. Ca carbonates and Ca phosphates are usually crystalline, but silica organisms (sponges, diatoms...) are always non crystalline minerals. Other examples include copper, iron and gold deposits involving bacteria. Biologically-formed minerals often have special uses such as magnetic sensors in magnetotactic bacteria (Fe3O4), gravity sensing devices (CaCO3, CaSO4, BaSO4) and iron storage and mobilization (Fe2O3•H2O in the protein ferritin).

In terms of taxonomic distribution, the most common biominerals are the phosphate and carbonate salts of calcium that are used in conjunction with organic polymers such as collagen and chitin to give structural support to bones and shells.[5] The structures of these biocomposite materials are highly controlled from the nanometer to the macroscopic level, resulting in complex architectures that provide multifunctional properties. Because this range of control over mineral growth is desirable for materials engineering applications, there is significant interest in understanding and elucidating the mechanisms of biologically controlled biomineralization.[6][7]

Biological roles

Among metazoans, biominerals composed of calcium carbonate, calcium phosphate or silica perform a variety of roles such as support, defense and feeding.[9] It is less clear what purpose biominerals serve in bacteria. One hypothesis is that cells create them to avoid entombment by their own metabolic byproducts. Iron oxide particles may also enhance their metabolism.[10]

Biology

If present on a super-cellular scale, biominerals are usually deposited by a dedicated organ, which is often defined very early in the embryological development. This organ will contain an organic matrix that facilitates and directs the deposition of crystals.[9] The matrix may be collagen, as in deuterostomes,[9] or based on chitin or other polysaccharides, as in molluscs.[11]

Shell formation in molluscs

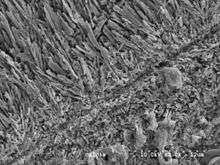

The mollusc shell is a biogenic composite material that has been the subject of much interest in materials science because of its unusual properties and its model character for biomineralization. Molluscan shells consist of 95–99% calcium carbonate by weight, while an organic component makes up the remaining 1–5%. The resulting composite has a fracture toughness ≈3000 times greater than that of the crystals themselves.[12] In the biomineralization of the mollusc shell, specialized proteins are responsible for directing crystal nucleation, phase, morphology, and growths dynamics and ultimately give the shell its remarkable mechanical strength. The application of biomimetic principles elucidated from mollusc shell assembly and structure may help in fabricating new composite materials with enhanced optical, electronic, or structural properties. The most described arrangement in mollusc shells is the nacre - prismatic shells, known in large shells as Pinna or the pearl oyster (Pinctada). Not only the structure of the layers differ, but their mineralogy and chemical composition also differ. Both contain organic components (proteins, sugars and lipids) and the organic components are characteristic of the layer, and of the species.[4] The structures and arrangements of mollusc shells are diverse, but they share some features: the main part of the shell is a crystalline Ca carbonate (aragonite, calcite), despite some amorphous Ca carbonate occurs; and despite they react as crystals, they never show angles and facets.[13] The examination of the inner structure of the prismatic units, nacreous tablets, foliated laths... shows irregular rounded granules.

Mineral production and degradation in fungi

Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that belong to the eukaryotic domain. Studies of their significant roles in geological processes, "geomycology", has shown that fungi are involved with biomineralization, biodegradation, and metal-fungal interactions.[14]

In studying fungi's roles in biomineralization, it has been found that fungi deposit minerals with the help of an organic matrix, such as a protein, that provides a nucleation site for the growth of biominerals.[15] Fungal growth may produce a copper-containing mineral precipitate, such as copper carbonate produced from a mixture of (NH4)2CO3 and CuCl2.[15] The production of the copper carbonate is produced in the presence of proteins made and secreted by the fungi.[15] These fungal proteins that are found extracellularly aid in the size and morphology of the carbonate minerals precipitated by the fungi.[15]

In addition to precipitating carbonate minerals, fungi can also precipitate uranium-containing phosphate biominerals in the presence of organic phosphorus that acts a substrate for the process.[16] The fungi produce a hyphal matrix, also known as mycelium, that localizes and accumulates the uranium minerals that have been precipitated.[16] Although uranium is often deemed as toxic towards living organisms, certain fungi such as Aspergillus niger and Paecilomyces javanicus can tolerate it.

Though minerals can be produced by fungi, they can also be degraded; mainly by oxalic-acid producing strains of fungi.[17] Oxalic acid production is increased in the presence of glucose for three organic acid producing fungi – Aspergillus niger, Serpula himantioides, and Trametes versicolor.[17] These fungi have been found to corrode apatite and galena minerals.[17] Degradation of minerals by fungi is carried out through a process known as neogenesis.[18] The order of most to least oxalic acid secreted by the fungi studied are Aspergillus niger, followed by Serpula himantioides, and finally Trametes versicolor.[17] These capabilities of certain groups of fungi have a major impact on corrosion, a costly problem for many industries and the economy.

Chemistry

The majority of biominerals fall into three distinct mineral classes: carbonates, silicates and phosphates.[19]

Carbonates

The major carbonates are CaCO3. The most common polymorphs in biomineralization are calcite (e.g. foraminifera, coccolithophores) and aragonite (e.g. corals), although metastable vaterite and amorphous calcium carbonate can also be important, either structurally [20][21] or as intermediate phases in biomineralization.[22][23] Some biominerals include a mixture of these phases in distinct, organised structural components (e.g. bivalve shells). Carbonates are particularly prevalent in marine environments, but also present in fresh water and terrestrial organisms.

Silicates

Silicates are particularly common in marine biominerals, where Diatoms and Radiolaria form frustules from hydrated amorphous silica (Opal).

Phosphates

The most common phosphate is hydroxyapatite, a calcium phosphate (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2) which is a primary constituent of bone, teeth, and fish scales.[24]

Other Minerals

Beyond these main three categories, there a number of less common types of biominerals, usually resulting from a need for specific physical properties or the organism inhabiting an unusual environment. For example, teeth that are primarily used for scraping hard substrates may be reinforced with particularly tough minerals, such as the iron minerals Magnetite in Chiton,[25] or Goethite in Limpets.[26] Gastropod molluscs living close to hydrothermal vents reinforce their carbonate shells with the iron-sulphur minerals pyrite and greigite.[27] Magnetotactic bacteria also employ magnetic iron minerals magnetite and greigite to produce magnetosomes to aid orientation and distribution in the sediments. Planktic acantharea (radiolaria) form strontium sulphate (Celestine) spicules.

Evolution

The first evidence of biomineralization dates to some 750 million years ago,[28][29] and sponge-grade organisms may have formed calcite skeletons 630 million years ago.[30] But in most lineages, biomineralization first occurred in the Cambrian or Ordovician periods.[31] Organisms used whichever form of calcium carbonate was more stable in the water column at the point in time when they became biomineralized,[32] and stuck with that form for the remainder of their biological history[33] (but see [34] for a more detailed analysis). The stability is dependent on the Ca/Mg ratio of seawater, which is thought to be controlled primarily by the rate of sea floor spreading, although atmospheric CO

2 levels may also play a role.[32]

Biomineralization evolved multiple times, independently,[35] and most animal lineages first expressed biomineralized components in the Cambrian period.[36] Many of the same processes are used in unrelated lineages, which suggests that biomineralization machinery was assembled from pre-existing "off-the-shelf" components already used for other purposes in the organism.[19] Although the biomachinery facilitating biomineralization is complex – involving signalling transmitters, inhibitors, and transcription factors – many elements of this 'toolkit' are shared between phyla as diverse as corals, molluscs, and vertebrates.[37] The shared components tend to perform quite fundamental tasks, such as designating that cells will be used to create the minerals, whereas genes controlling more finely tuned aspects that occur later in the biomineralization process – such as the precise alignment and structure of the crystals produced – tend to be uniquely evolved in different lineages.[9][38] This suggests that Precambrian organisms were employing the same elements, albeit for a different purpose — perhaps to avoid the inadvertent precipitation of calcium carbonate from the supersaturated Proterozoic oceans.[37] Forms of mucus that are involved in inducing mineralization in most metazoan lineages appear to have performed such an anticalcifatory function in the ancestral state.[39] Further, certain proteins that would originally have been involved in maintaining calcium concentrations within cells[40] are homologous to all metazoans, and appear to have been co-opted into biomineralization after the divergence of the metazoan lineages.[41] The galaxins are one probable example of a gene being co-opted from a different ancestral purpose into controlling biomineralization, in this case being 'switched' to this purpose in the Triassic scleractinian corals; the role performed appears to be functionally identical to the unrelated pearlin gene in molluscs.[42] Carbonic anhydrase serves a role in mineralization in sponges, as well as metazoans, implying an ancestral role.[43] Far from being a rare trait that evolved a few times and remained stagnant, biomineralization pathways in fact evolved many times and are still evolving rapidly today; even within a single genus it is possible to detect great variation within a single gene family.[38]

The homology of biomineralization pathways is underlined by a remarkable experiment whereby the nacreous layer of a molluscan shell was implanted into a human tooth, and rather than experiencing an immune response, the molluscan nacre was incorporated into the host bone matrix. This points to the exaptation of an original biomineralization pathway.

The most ancient example of biomineralization, dating back 2 billion years, is the deposition of magnetite, which is observed in some bacteria, as well as the teeth of chitons and the brains of vertebrates; it is possible that this pathway, which performed a magnetosensory role in the common ancestor of all bilaterians, was duplicated and modified in the Cambrian to form the basis for calcium-based biomineralization pathways.[44] Iron is stored in close proximity to magnetite-coated chiton teeth, so that the teeth can be renewed as they wear. Not only is there a marked similarity between the magnetite deposition process and enamel deposition in vertebrates but some vertebrates even have comparable iron storage facilities near their teeth.[45]

| Type of mineralization | Examples of organisms |

|---|---|

| Calcium carbonate (calcite or aragonite) |

|

| Silica |

|

| Apatite (phosphate carbonate) |

|

Astrobiology

It has been suggested that biominerals could be important indicators of extraterrestrial life and thus could play an important role in the search for past or present life on Mars. Furthermore, organic components (biosignatures) that are often associated with biominerals are believed to play crucial roles in both pre-biotic and biotic reactions.[46]

On January 24, 2014, NASA reported that current studies by the Curiosity and Opportunity rovers on the planet Mars will now be searching for evidence of ancient life, including a biosphere based on autotrophic, chemotrophic and/or chemolithoautotrophic microorganisms, as well as ancient water, including fluvio-lacustrine environments (plains related to ancient rivers or lakes) that may have been habitable.[47][48][49][50] The search for evidence of habitability, taphonomy (related to fossils), and organic carbon on the planet Mars is now a primary NASA objective.[47][48]

Potential applications

Most traditional approaches to synthesis of nanoscale materials are energy inefficient, requiring stringent conditions (e.g., high temperature, pressure or pH) and often produce toxic byproducts. Furthermore, the quantities produced are small, and the resultant material is usually irreproducible because of the difficulties in controlling agglomeration.[51] In contrast, materials produced by organisms have properties that usually surpass those of analogous synthetically manufactured materials with similar phase composition. Biological materials are assembled in aqueous environments under mild conditions by using macromolecules. Organic macromolecules collect and transport raw materials and assemble these substrates and into short- and long-range ordered composites with consistency and uniformity. The aim of biomimetics is to mimic the natural way of producing minerals such as apatites. Many man-made crystals require elevated temperatures and strong chemical solutions, whereas the organisms have long been able to lay down elaborate mineral structures at ambient temperatures. Often, the mineral phases are not pure but are made as composites that entail an organic part, often protein, which takes part in and controls the biomineralisation. These composites are often not only as hard as the pure mineral but also tougher, as the micro-environment controls biomineralisation.

Uranium contaminants in groundwater

Biomineralization may be used to remediate groundwater contaminated with uranium.[52] The biomineralization of uranium primarily involves the precipitation of uranium phosphate minerals associated with the release of phosphate by microorganisms. Negatively charged ligands at the surface of the cells attract the positively charged uranyl ion (UO22+). If the concentrations of phosphate and UO22+ are sufficiently high, minerals such as autunite (Ca(UO2)2(PO4)2•10-12H2O) or polycrystalline HUO2PO4 may form thus reducing the mobility of UO22+. Compared to the direct addition of inorganic phosphate to contaminated groundwater, biomineralization has the advantage that the ligands produced by microbes will target uranium compounds more specifically rather than react actively with all aqueous metals. Stimulating bacterial phosphatase activity to liberate phosphate under controlled conditions limits the rate of bacterial hydrolysis of organophosphate and the release of phosphate to the system, thus avoiding clogging of the injection location with metal phosphate minerals.[52] The high concentration of ligands near the cell surface also provides nucleation foci for precipitation, which leads to higher efficiency than chemical precipitation.[53]

List of minerals

Examples of biogenic minerals include:[54]

- Apatite in bones and teeth.

- Aragonite, calcite, fluorite in vestibular systems (part of the inner ear) of vertebrates.

- Aragonite and calcite in travertine and biogenic silica (siliceous sinter, opal) deposited through algal action.

- Hydroxylapatite formed by mitochondria.

- Magnetite and greigite formed by magnetotactic bacteria.

- Pyrite and marcasite in sedimentary rocks deposited by sulfate-reducing bacteria.

- Quartz and diamonds formed from bacterial action on fossil fuels (gas, oil, coal).

- Goethite found as filaments in limpet teeth.

See also

- Biocrystallization

- Biointerface

- Biomineralising polychaetes

- Bone mineral

References

Footnotes

- The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry defines biomineralization as "mineralization caused by cell-mediated phenomena" and notes that it "is a process generally concomitant to biodegradation".[1]

Notes

- Vert, Michel; Doi, Yoshiharu; Hellwich, Karl-Heinz; Hess, Michael; Hodge, Philip; Kubisa, Przemyslaw; Rinaudo, Marguerite; Schué, François (2012). "Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 84 (2): 377–410. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04.

- Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Rol, K.O. Sigel, eds. (2008). Biomineralization: From Nature to Application. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 4. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-03525-2.

- Weiner, Stephen; Lowenstam, Heinz A. (1989). On biomineralization. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504977-0.

- Jean-Pierre Cuif; Yannicke Dauphin; James E. Sorauf (2011). Biominerals and fossils through time. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-87473-1.

- Vinn, O. (2013). "Occurrence formation and function of organic sheets in the mineral tube structures of Serpulidae (Polychaeta Annelida)". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e75330. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875330V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075330. PMC 3792063. PMID 24116035.

- Boskey, A. L. (1998). "Biomineralization: conflicts, challenges, and opportunities". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. Supplement. 30–31: 83–91. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(1998)72:30/31+<83::AID-JCB12>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 9893259.

- Sarikaya, M. (1999). "Biomimetics: Materials fabrication through biology". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (25): 14183–14185. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9614183S. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.25.14183. PMC 33939. PMID 10588672.

- Vert, Michel; Doi, Yoshiharu; Hellwich, Karl-Heinz; Hess, Michael; Hodge, Philip; Kubisa, Przemyslaw; Rinaudo, Marguerite; Schué, François (11 January 2012). "Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 84 (2): 377–410. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04.

- Livingston, B.; Killian, C.; Wilt, F.; Cameron, A.; Landrum, M.; Ermolaeva, O.; Sapojnikov, V.; Maglott, D.; Buchanan, A.; Ettensohn, C. A. (2006). "A genome-wide analysis of biomineralization-related proteins in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus". Developmental Biology. 300 (1): 335–348. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.047. PMID 16987510.

- Fortin, D. (12 March 2004). "Enhanced: What Biogenic Minerals Tell Us". Science. 303 (5664): 1618–1619. doi:10.1126/science.1095177. PMID 15016984.

- Checa, A.; Ramírez-Rico, J.; González-Segura, A.; Sánchez-Navas, A. (2009). "Nacre and false nacre (foliated aragonite) in extant monoplacophorans (=Tryblidiida: Mollusca)". Die Naturwissenschaften. 96 (1): 111–122. Bibcode:2009NW.....96..111C. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0461-1. PMID 18843476. S2CID 10214928.

- Currey, J. D. (1999). "The design of mineralised hard tissues for their mechanical functions". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 202 (Pt 23): 3285–3294. PMID 10562511.

- Cuif J.P., Dauphin Y. (2003). Les étapes de la découverte des rapports entre la terre et la vie : une introduction à la paléontologie. Paris: Éditions scientifiques GB. ISBN 978-2847030082. OCLC 77036366.

- Gadd, Geoffrey M. (2007-01-01). "Geomycology: biogeochemical transformations of rocks, minerals, metals and radionuclides by fungi, bioweathering and bioremediation". Mycological Research. 111 (1): 3–49. doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2006.12.001. PMID 17307120.

- Li, Qianwei; Gadd, Geoffrey Michael (2017-08-10). "Biosynthesis of copper carbonate nanoparticles by ureolytic fungi". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 101 (19): 7397–7407. doi:10.1007/s00253-017-8451-x. ISSN 1432-0614. PMC 5594056. PMID 28799032.

- Liang, Xinjin; Hillier, Stephen; Pendlowski, Helen; Gray, Nia; Ceci, Andrea; Gadd, Geoffrey Michael (2015-06-01). "Uranium phosphate biomineralization by fungi". Environmental Microbiology. 17 (6): 2064–2075. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12771. ISSN 1462-2920. PMID 25580878. S2CID 9699895.

- Adeyemi, Ademola O.; Gadd, Geoffrey M. (2005-06-01). "Fungal degradation of calcium-, lead- and silicon-bearing minerals". Biometals. 18 (3): 269–281. doi:10.1007/s10534-005-1539-2. ISSN 0966-0844. PMID 15984571. S2CID 35004304.

- Adamo, Paola; Violante, Pietro (2000-05-01). "Weathering of rocks and neogenesis of minerals associated with lichen activity". Applied Clay Science. 16 (5): 229–256. doi:10.1016/S0169-1317(99)00056-3.

- Knoll, A.H. (2004). "Biomineralization and evolutionary history" (PDF). In P.M. Dove; J.J. DeYoreo; S. Weiner (eds.). Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-20.

- Pokroy, Boaz; Kabalah-Amitai, Lee; Polishchuk, Iryna; DeVol, Ross T.; Blonsky, Adam Z.; Sun, Chang-Yu; Marcus, Matthew A.; Scholl, Andreas; Gilbert, Pupa U.P.A. (2015-10-13). "Narrowly Distributed Crystal Orientation in Biomineral Vaterite". Chemistry of Materials. 27 (19): 6516–6523. arXiv:1609.05449. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b01542. ISSN 0897-4756.

- Neues, Frank; Hild, Sabine; Epple, Matthias; Marti, Othmar; Ziegler, Andreas (July 2011). "Amorphous and crystalline calcium carbonate distribution in the tergite cuticle of moulting Porcellio scaber (Isopoda, Crustacea)". Journal of Structural Biology. 175 (1): 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2011.03.019. PMID 21458575.

- Jacob, D. E.; Wirth, R.; Agbaje, O. B. A.; Branson, O.; Eggins, S. M. (December 2017). "Planktic foraminifera form their shells via metastable carbonate phases". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 1265. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.1265J. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00955-0. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5668319. PMID 29097678.

- Mass, Tali; Giuffre, Anthony J.; Sun, Chang-Yu; Stifler, Cayla A.; Frazier, Matthew J.; Neder, Maayan; Tamura, Nobumichi; Stan, Camelia V.; Marcus, Matthew A.; Gilbert, Pupa U. P. A. (2017-09-12). "Amorphous calcium carbonate particles form coral skeletons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (37): E7670–E7678. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E7670M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1707890114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5604026. PMID 28847944.

- Onozato, Hiroshi (1979). "Studies on fish scale formation and resorption". Cell and Tissue Research. 201 (3): 409–422. doi:10.1007/BF00236999. PMID 574424. S2CID 2222515.

- Joester, Derk; Brooker, Lesley R. (2016-07-05), Faivre, Damien (ed.), "The Chiton Radula: A Model System for Versatile Use of Iron Oxides*", Iron Oxides (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 177–206, doi:10.1002/9783527691395.ch8, ISBN 978-3-527-33882-5

- Barber, Asa H.; Lu, Dun; Pugno, Nicola M. (2015-04-06). "Extreme strength observed in limpet teeth". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 12 (105): 20141326. doi:10.1098/rsif.2014.1326. ISSN 1742-5689. PMC 4387522. PMID 25694539.

- Chen, Chong; Linse, Katrin; Copley, Jonathan T.; Rogers, Alex D. (August 2015). "The 'scaly-foot gastropod': a new genus and species of hydrothermal vent-endemic gastropod (Neomphalina: Peltospiridae) from the Indian Ocean". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 81 (3): 322–334. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyv013. ISSN 0260-1230.

- Porter, S. (2011). "The rise of predators". Geology. 39 (6): 607–608. Bibcode:2011Geo....39..607P. doi:10.1130/focus062011.1.

- Cohen, P. A.; Schopf, J. W.; Butterfield, N. J.; Kudryavtsev, A. B.; MacDonald, F. A. (2011). "Phosphate biomineralization in mid-Neoproterozoic protists". Geology. 39 (6): 539–542. Bibcode:2011Geo....39..539C. doi:10.1130/G31833.1. S2CID 32229787.

- Maloof, A. C.; Rose, C. V.; Beach, R.; Samuels, B. M.; Calmet, C. C.; Erwin, D. H.; Poirier, G. R.; Yao, N.; Simons, F. J. (2010). "Possible animal-body fossils in pre-Marinoan limestones from South Australia". Nature Geoscience. 3 (9): 653–659. Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..653M. doi:10.1038/ngeo934. S2CID 13171894.

- Wood, R. A. (2002). "Proterozoic Modular Biomineralized Metazoan from the Nama Group, Namibia". Science. 296 (5577): 2383–2386. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.2383W. doi:10.1126/science.1071599. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 12089440.

- Zhuravlev, A. Y.; Wood, R. A. (2008). "Eve of biomineralization: Controls on skeletal mineralogy" (PDF). Geology. 36 (12): 923. Bibcode:2008Geo....36..923Z. doi:10.1130/G25094A.1.

- Porter, S. M. (Jun 2007). "Seawater chemistry and early carbonate biomineralization". Science. 316 (5829): 1302. Bibcode:2007Sci...316.1302P. doi:10.1126/science.1137284. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17540895.

- Maloof, A. C.; Porter, S. M.; Moore, J. L.; Dudas, F. O.; Bowring, S. A.; Higgins, J. A.; Fike, D. A.; Eddy, M. P. (2010). "The earliest Cambrian record of animals and ocean geochemical change". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 122 (11–12): 1731–1774. Bibcode:2010GSAB..122.1731M. doi:10.1130/B30346.1. S2CID 6694681.

- Murdock, D. J. E.; Donoghue, P. C. J. (2011). "Evolutionary Origins of Animal Skeletal Biomineralization". Cells Tissues Organs. 194 (2–4): 98–102. doi:10.1159/000324245. PMID 21625061. S2CID 45466684.

- Kouchinsky, A.; Bengtson, S.; Runnegar, B.; Skovsted, C.; Steiner, M.; Vendrasco, M. (2011). "Chronology of early Cambrian biomineralization". Geological Magazine. 149 (2): 1. Bibcode:2012GeoM..149..221K. doi:10.1017/S0016756811000720.

- Westbroek, P.; Marin, F. (1998). "A marriage of bone and nacre". Nature. 392 (6679): 861–862. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..861W. doi:10.1038/31798. PMID 9582064. S2CID 4348775.

- Jackson, D.; McDougall, C.; Woodcroft, B.; Moase, P.; Rose, R.; Kube, M.; Reinhardt, R.; Rokhsar, D.; Montagnani, C.; Joubert, C.; Piquemal, D.; Degnan, B. M. (2010). "Parallel evolution of nacre building gene sets in molluscs". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 27 (3): 591–608. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp278. PMID 19915030.

- Marin, F; Smith, M; Isa, Y; Muyzer, G; Westbroek, P (1996). "Skeletal matrices, muci, and the origin of invertebrate calcification". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (4): 1554–9. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.1554M. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.4.1554. PMC 39979. PMID 11607630.

- H. A. Lowenstam; L. Margulis (1980). "Evolutionary prerequisites for early phanerozoic calcareous skeletons". BioSystems. 12 (1–2): 27–41. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(80)90036-2. PMID 6991017.

- Lowenstam, H.; Margulis, L. (1980). "Evolutionary prerequisites for early phanerozoic calcareous skeletons". Biosystems. 12 (1–2): 27–41. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(80)90036-2. PMID 6991017.

- Reyes-Bermudez, A.; Lin, Z.; Hayward, D.; Miller, D.; Ball, E. (2009). "Differential expression of three galaxin-related genes during settlement and metamorphosis in the scleractinian coral Acropora millepora". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9: 178. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-178. PMC 2726143. PMID 19638240.

- Jackson, D.; Macis, L.; Reitner, J.; Degnan, B.; Wörheide, G. (2007). "Sponge paleogenomics reveals an ancient role for carbonic anhydrase in skeletogenesis". Science. 316 (5833): 1893–1895. Bibcode:2007Sci...316.1893J. doi:10.1126/science.1141560. PMID 17540861.

- Kirschvink J.L. & Hagadorn, J.W. (2000). "10 A Grand Unified theory of Biomineralization.". In Bäuerlein, E. (ed.). The Biomineralisation of Nano- and Micro-Structures. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. pp. 139–150.

- Towe, K.; Lowenstam, H. (1967). "Ultrastructure and development of iron mineralization in the radular teeth of Cryptochiton stelleri (mollusca)". Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 17 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/S0022-5320(67)80015-7. PMID 6017357.

- MEPAG Astrobiology Field Laboratory Science Steering Group (September 26, 2006). "Final report of the MEPAG Astrobiology Field Laboratory Science Steering Group (AFL-SSG)" (.doc). In Steele, Andrew; Beaty, David (eds.). The Astrobiology Field Laboratory. U.S.A.: Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG) - NASA. p. 72. Retrieved 2009-07-22.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Grotzinger, John P. (January 24, 2014). "Introduction to Special Issue - Habitability, Taphonomy, and the Search for Organic Carbon on Mars". Science. 343 (6169): 386–387. Bibcode:2014Sci...343..386G. doi:10.1126/science.1249944. PMID 24458635.

- Various (January 24, 2014). "Special Issue - Table of Contents - Exploring Martian Habitability". Science. 343 (6169): 345–452. Retrieved January 24, 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Various (January 24, 2014). "Special Collection - Curiosity - Exploring Martian Habitability". Science. Retrieved January 24, 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Grotzinger, J.P.; et al. (January 24, 2014). "A Habitable Fluvio-Lacustrine Environment at Yellowknife Bay, Gale Crater, Mars". Science. 343 (6169): 1242777. Bibcode:2014Sci...343A.386G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.455.3973. doi:10.1126/science.1242777. PMID 24324272.

- Thomas, George Brinton; Komarneni, Sridhar; Parker, John (1993). Nanophase and Nanocomposite Materials: Symposium Held December 1–3, 1992, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. (Materials Research Society Symposium Proceedings). Pittsburgh, Pa: Materials Research Society. ISBN 978-1-55899-181-1.

- Newsome, L.; Morris, K. & Lloyd, J. R. (2014). "The biogeochemistry and bioremediation of uranium and other priority radionuclides". Chemical Geology. 363: 164–184. Bibcode:2014ChGeo.363..164N. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.10.034.

- Lloyd, J. R. & Macaskie, L. E (2000). Environmental microbe-metal interactions: Bioremediation of radionuclide-containing wastewaters. Washington, DC: ASM Press. pp. 277–327. ISBN 978-1-55581-195-2.

- Corliss, William R. (Nov–Dec 1989). "Biogenic Minerals". Science Frontiers. 66.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Key reference

- Lowenstam, H. A. (13 March 1981). "Minerals Formed by Organisms". Science. 211 (4487): 1126–1131. Bibcode:1981Sci...211.1126L. doi:10.1126/science.7008198. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1685216. PMID 7008198. S2CID 31036238.

Additional sources

- Addadi, L. & S. Weiner (1992). "Control And Design Principles In Biological Mineralization". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 31 (2): 153–169. doi:10.1002/anie.199201531. Archived from the original (abstract) on 2012-12-17.

- Boskey, A.L. (2003). "Biomineralization: An overview". Connective Tissue Research. 44 (Supplement 1): 5–9. doi:10.1080/713713622. PMID 12952166.

- McPhee, Joseph (2006). "The Little Workers of the Mining Industry". Science Creative Quarterly (2). Retrieved 2006-11-03.

- Schmittner, Karl-Erich & Giresse, Pierre (1999). "Micro-environmental controls on biomineralization: superficial processes of apatite and calcite precipitation in Quaternary soils, Roussillon, France". Sedimentology. 46 (3): 463–476. Bibcode:1999Sedim..46..463S. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3091.1999.00224.x.

- Weiner, S. & L. Addadi (1997). "Design strategies in mineralized biological materials". Journal of Materials Chemistry. 7 (5): 689–702. doi:10.1039/a604512j.

- Dauphin, Y. (2005). Biomineralization. Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry (R.B. King Ed)., Wiley & Sons. 1. pp. 391–404. ISBN 978-0-521-87473-1.

- Cuif, J.P. & Sorauf, J.E. (2001). "Biomineralization and diagenesis in the Scleractinia : part I, biomineralization". Bull. Tohoku Univ. Museum. 1: 144–151.

- Dauphin, Y. (2002). "Structures, organo mineral compositions and diagenetic changes in biominerals". Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 7 (1–2): 133–138. doi:10.1016/S1359-0294(02)00013-4.

- Kupriyanova, E.K., Vinn, O., Taylor, P.D., Schopf, J.W., Kudryavtsev, A.B. and Bailey-Brock, J. (2014). "Serpulids living deep: calcareous tubeworms beyond the abyss". Deep-Sea Research Part I. 90: 91–104. Bibcode:2014DSRI...90...91K. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2014.04.006. Retrieved 2014-01-09.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Vinn, O., ten Hove, H.A. and Mutvei, H. (2008). "Ultrastructure and mineral composition of serpulid tubes (Polychaeta, Annelida)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 154 (4): 633–650. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00421.x. Retrieved 2014-01-09.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Vinn, O. (2013). "Occurrence, Formation and Function of Organic Sheets in the Mineral Tube Structures of Serpulidae (Polychaeta, Annelida)". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e75330. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875330V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075330. PMC 3792063. PMID 24116035.

External links

- An overview of the bacteria involved in biomineralization from the Science Creative Quarterly

- 'Data and literature on modern and fossil Biominerals': http://biomineralisation.blogspot.fr

- Minerals and the Origins of Life (Robert Hazen, NASA) (video, 60m, April 2014).

- Biomineralization web-book: bio-mineral.org

- Special German Research Project About the Principles of Biomineralization