Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis, also known as snail fever and bilharzia,[9] is a disease caused by parasitic flatworms called schistosomes.[5] The urinary tract or the intestines may be infected.[5] Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, or blood in the urine.[5] Those who have been infected for a long time may experience liver damage, kidney failure, infertility, or bladder cancer.[5] In children, it may cause poor growth and learning difficulty.[5]

| Schistosomiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bilharzia, snail fever, Katayama fever[1][2] |

| |

| 11-year-old boy with abdominal fluid and portal hypertension due to schistosomiasis (Agusan del Sur, Philippines) | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, blood in the urine[5] |

| Complications | Liver damage, kidney failure, infertility, bladder cancer[5] |

| Causes | Schistosomes from freshwater snails[5] |

| Diagnostic method | Finding eggs of the parasite in urine or stool, antibodies in blood[5] |

| Prevention | Access to clean water[5] |

| Medication | Praziquantel[5] |

| Frequency | 252 million (2015)[6] |

| Deaths | 4,400–200,000[7][8] |

The disease is spread by contact with fresh water contaminated with the parasites.[5] These parasites are released from infected freshwater snails.[5] The disease is especially common among children in developing countries, as they are more likely to play in contaminated water.[5] Other high-risk groups include farmers, fishermen, and people using unclean water during daily living.[5] It belongs to the group of helminth infections.[10] Diagnosis is by finding eggs of the parasite in a person's urine or stool.[5] It can also be confirmed by finding antibodies against the disease in the blood.[5]

Methods to prevent the disease include improving access to clean water and reducing the number of snails.[5] In areas where the disease is common, the medication praziquantel may be given once a year to the entire group.[5] This is done to decrease the number of people infected, and consequently, the spread of the disease.[5] Praziquantel is also the treatment recommended by the World Health Organization for those who are known to be infected.[5]

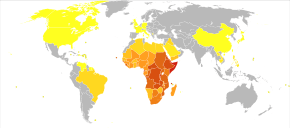

Schistosomiasis affected about 252 million people worldwide in 2015.[6] An estimated 4,400 to 200,000 people die from it each year.[7][8] The disease is most commonly found in Africa, Asia, and South America.[5] Around 700 million people, in more than 70 countries, live in areas where the disease is common.[7][11] In tropical countries, schistosomiasis is second only to malaria among parasitic diseases with the greatest economic impact.[12] Schistosomiasis is listed as a neglected tropical disease.[13]

Signs and symptoms

Many individuals do not experience symptoms. If symptoms do appear, they usually take 4–6 weeks from the time of infection. The first symptom of the disease may be a general feeling of illness. Within 12 hours of infection, an individual may complain of a tingling sensation or light rash, commonly referred to as "swimmer's itch", due to irritation at the point of entrance. The rash that may develop can mimic scabies and other types of rashes. Other symptoms can occur 2–10 weeks later and can include fever, aching, a cough, diarrhea, chills, or gland enlargement. These symptoms can also be related to avian schistosomiasis, which does not cause any further symptoms in humans.

The manifestations of schistosomal infection vary over time as the cercariae, and later adult worms and their eggs, migrate through the body.[14] If eggs migrate to the brain or spinal cord, seizures, paralysis, or spinal-cord inflammation are possible.[15]

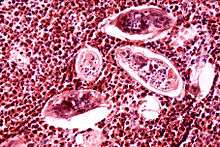

Intestinal schistosomiasis

In intestinal schistosomiasis, eggs become lodged in the intestinal wall and cause an immune system reaction called a granulomatous reaction. This immune response can lead to obstruction of the colon and blood loss. The infected individual may have what appears to be a potbelly. Eggs can also become lodged in the liver, leading to high blood pressure through the liver, enlarged spleen, the buildup of fluid in the abdomen, and potentially life-threatening dilations or swollen areas in the esophagus or gastrointestinal tract that can tear and bleed profusely (esophageal varices). In rare instances, the central nervous system is affected. Individuals with chronic active schistosomiasis may not complain of typical symptoms.

Dermatitis

The first potential reaction is an itchy, papular rash[16]:432 that results from cercariae penetrating the skin, often in a person's first infection.[14] The round bumps are usually one to three centimeters across.[17] Because people living in affected areas have often been repeatedly exposed, acute reactions are more common in tourists and migrants.[18] The rash can occur between the first few hours and a week after exposure and lasts for several days.[17] A similar, more severe reaction called "swimmer's itch" reaction can also be caused by cercariae from animal trematodes that often infect birds.[14][19]

Katayama fever

Another primary condition, called Katayama fever, may also develop from infection with these worms, and it can be very difficult to recognize. Symptoms include fever, lethargy, the eruption of pale temporary bumps associated with severe itching (urticarial) rash, liver and spleen enlargement, and bronchospasm.

Acute schistosomiasis (Katayama fever) may occur weeks or months after the initial infection as a systemic reaction against migrating schistosomulae as they pass through the bloodstream through the lungs to the liver.[14] Similarly to swimmer's itch, Katayama fever is more commonly seen in people with their first infection such as migrants and tourists. It is seen, however, in native residents of China infected with S. japonicum.[20] Symptoms include:

- Dry cough with changes on chest X-ray

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Muscle aches

- Malaise

- Abdominal pain

- Enlargement of both the liver and the spleen

The symptoms usually get better on their own, but a small proportion of people have persistent weight loss, diarrhea, diffuse abdominal pain, and rash.[14]

Chronic disease

In long-established disease, adult worms lay eggs that can cause inflammatory reactions. The eggs secrete proteolytic enzymes that help them migrate to the bladder and intestines to be shed. The enzymes also cause an eosinophilic inflammatory reaction when eggs get trapped in tissues or embolize to the liver, spleen, lungs, or brain.[14] The long-term manifestations are dependent on the species of schistosome, as the adult worms of different species migrate to different areas.[21] Many infections are mildly symptomatic, with anemia and malnutrition being common in endemic areas.[22]

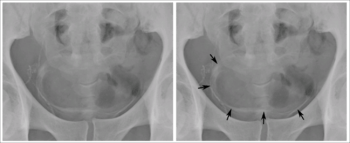

Genitourinary disease

The worms of S. haematobium migrate to the veins around the bladder and ureters.[21] This can lead to blood in the urine 10 to 12 weeks after infection.[14][17] Over time, fibrosis can lead to obstruction of the urinary tract, hydronephrosis, and kidney failure.[14][17] Bladder cancer diagnosis and mortality are generally elevated in affected areas; efforts to control schistosomiasis in Egypt have led to decreases in the bladder cancer rate.[17][23] The risk of bladder cancer appears to be especially high in male smokers, perhaps due to chronic irritation of the bladder lining allowing it to be exposed to carcinogens from smoking.[19][21]

In women, genitourinary disease can also include genital lesions that may lead to increased rates of HIV transmission.[17][24][25]

Gastrointestinal disease

The worms of S. mansoni and S. japonicum migrate to the veins of the gastrointestinal tract and liver.[19] Eggs in the gut wall can lead to pain, blood in the stool, and diarrhea (especially in children).[19] Severe disease can lead to narrowing of the colon or rectum.[17] Eggs also migrate to the liver leading to fibrosis in 4 to 8% of people with chronic infection, mainly those with long-term heavy infection.[19] S. mansoni infection epidemiologically overlaps with high HIV prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa, where gastrointestinal schistosomiasis has been linked to increased HIV transmission.[24]

Central nervous system disease

Central nervous system lesions occur occasionally. Cerebral granulomatous disease may be caused by S. japonicum eggs in the brain. Communities in China affected by S. japonicum have rates of seizures eight times higher than baseline.[19] Similarly, granulomatous lesions from S. mansoni and S. haematobium eggs in the spinal cord can lead to transverse myelitis with flaccid paraplegia.[26] Cerebral granulomatous infection may also be caused by S. mansoni. In situ egg deposition following the anomalous migration of the adult worm appears to be the only mechanism by which Schistosoma can reach the central nervous system in these patients. The destructive action on the nervous tissue and the mass effect produced by a large number of eggs surrounded by multiple, large granulomas in circumscribed areas of the brain characterize the pseudotumoral form of neuroschistosomiasis and are responsible for the appearance of clinical manifestations: headache, hemiparesis, altered mental status, vertigo, visual abnormalities, seizures, and ataxia. In cases with advanced hepatosplenic and urinary schistosomiasis, the continuous embolization of eggs from the portal mesenteric system (S. mansoni) or portal mesenteric-pelvic system (S. haematobium) to the brain, results in a sparse distribution of eggs associated with scant periovular inflammatory reaction, usually with little or no clinical significance.[27]

Transmission

Infected individuals release Schistosoma eggs into water via their fecal material or urine.[28] After larvae hatch from these eggs, the larvae infect a very specific type of freshwater snail. For example, in S. haematobium and S. intercalatum it is snails of the genus Bulinus, in S. mansoni it is Biomphalaria, and in S. japonicum it is Oncomelania.[29] The Schistosoma larvae undergo the next phase of their lifecycles in these snails, spending their time reproducing and developing. Once this step has been completed, the parasite leaves the snail and enters the water column. The parasite can live in the water for only 48 hours without a mammalian host. Once a host has been found, the worm enters its blood vessels. For several weeks, the worm remains in the vessels, continuing its development into its adult phase. When maturity is reached, mating occurs and eggs are produced. Eggs enter the bladder/intestine and are excreted through urine and feces and the process repeats. If the eggs do not get excreted, they can become engrained in the body tissues and cause a variety of problems such as immune reactions and organ damage.

Humans encounter larvae of the Schistosoma parasite when they enter contaminated water while bathing, playing, swimming, washing, fishing, or walking through the water.[30][31][28]

Diagnosis

Identification of eggs in stools

Diagnosis of infection is confirmed by the identification of eggs in stools. Eggs of S. mansoni are about 140 by 60 µm in size and have a lateral spine. The diagnosis is improved through the use of the Kato technique, a semiquantitative stool examination technique. Other methods that can be used are enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, circumoval precipitation test, and alkaline phosphatase immunoassay.[32]

Microscopic identification of eggs in stool or urine is the most practical method for diagnosis. Stool examination should be performed when infection with S. mansoni or S. japonicum is suspected, and urine examination should be performed if S. haematobium is suspected. Eggs can be present in the stool in infections with all Schistosoma species. The examination can be performed on a simple smear (1 to 2 mg of fecal material). Because eggs may be passed intermittently or in small numbers, their detection is enhanced by repeated examinations or concentration procedures, or both. In addition, for field surveys and investigational purposes, the egg output can be quantified by using the Kato-Katz technique (20 to 50 mg of fecal material) or the Ritchie technique. Eggs can be found in the urine in infections with S. haematobium (recommended time for collection: between noon and 3 PM) and with S. japonicum. Quantification is possible by using filtration through a nucleopore filter membrane of a standard volume of urine followed by egg counts on the membrane. Tissue biopsy (rectal biopsy for all species and biopsy of the bladder for S. haematobium) may demonstrate eggs when stool or urine examinations are negative.[33]

Identification of microhematuria in urine using urine reagent strips is more accurate than circulating antigen tests in the identification of active schistosomiasis in endemic areas.[34]

Antibody detection

Antibody detection can be useful to indicate schistosome infection in people who have traveled to areas where schistosomiasis is common and in whom eggs cannot be demonstrated in fecal or urine specimens. Test sensitivity and specificity vary widely among the many tests reported for the serologic diagnosis of schistosomiasis and are dependent on both the type of antigen preparations used (crude, purified, adult worm, egg, cercarial) and the test procedure.[33]

At the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a combination of tests with purified adult worm antigens is used for antibody detection. All serum specimens are tested by FAST-ELISA using S. mansoni adult microsomal antigen. A positive reaction (greater than 9 units/µl serum) indicates infection with Schistosoma species. Sensitivity for S. mansoni infection is 99%, 95% for S. haematobium infection, and less than 50% for S. japonicum infection. Specificity of this assay for detecting schistosome infection is 99%. Because test sensitivity with the FAST-ELISA is reduced for species other than S. mansoni, immunoblots of the species appropriate to the patient's travel history are also tested to ensure detection of S. haematobium and S. japonicum infections. Immunoblots with adult worm microsomal antigens are species-specific, so a positive reaction indicates the infecting species. The presence of antibody is indicative only of schistosome infection at some time and cannot be correlated with clinical status, worm burden, egg production, or prognosis. Where a person has traveled can help determine which Schistosoma species to test for by immunoblot.[33]

In 2005, a field evaluation of a novel handheld microscope was undertaken in Uganda for the diagnosis of intestinal schistosomiasis by a team led by Russell Stothard from the Natural History Museum of London, working with the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, London.[35]

Molecular diagnostics

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based testing is accurate and rapid.[36] However, it is not frequently used in countries where the disease is common due to the cost of the equipment and the technical expertise required to run the tests.[36] Using a microscope to detect eggs costs about US$0.40 per test whereas PCR is about $US 7 per test as of 2019.[37] Loop-mediated isothermal amplification are being studied as they are lower cost.[36] LAMP testing is not commercially available as of 2019.[37]

Prevention

Many countries are working towards eradicating the disease. The World Health Organization is promoting these efforts. In some cases, urbanization, pollution, and the consequent destruction of snail habitat have reduced exposure, with a subsequent decrease in new infections. The drug praziquantel is used for prevention in high-risk populations living in areas where the disease is common.[38] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises avoiding drinking or coming into contact with contaminated water in areas where schistosomiasis is common.[39]

A 2014 review found tentative evidence that increasing access to clean water and sanitation reduces schistosome infection.[40]

Snails, dams, and prawns

For many years from the 1950s onwards, vast dams and irrigation schemes were constructed, causing a massive rise in water-borne infections from schistosomiasis. The detailed specifications laid out in various United Nations documents since the 1950s could have minimized this problem. Irrigation schemes can be designed to make it hard for the snails to colonize the water and to reduce the contact with the local population.[41] Even though guidelines on how to design these schemes to minimise the spread of the disease had been published years before, the designers were unaware of them.[42] The dams appear to have reduced the population of the large migratory prawn Macrobrachium. After the construction of fourteen large dams, greater increases in schistosomiasis occurred in the historical habitats of native prawns than in other areas. Further, at the 1986 Diama Dam on the Senegal River, restoring prawns upstream of the dam reduced both snail density and the human schistosomiasis reinfection rate.[43][44]

Integrated strategy in China

In China, the national strategy for schistosomiasis control has shifted three times since it was first initiated: transmission control strategy (from mid-1950s to early 1980s), morbidity control strategy (from mid-1980s to 2003), and the "new integrated strategy" (2004 to present). The morbidity control strategy focused on synchronous chemotherapy for humans and bovines and the new strategy developed in 2004 intervenes in the transmission pathway of schistosomiasis, mainly including replacement of bovines with machines, prohibition of grazing cattle in the grasslands, improving sanitation, installation of fecal-matter containers on boats, praziquantel drug therapy, snail control, and health education. A 2018 review found that the "new integrated strategy" was highly effective to reducing the rate of S. japonicum infection in both humans and the intermediate host snails and reduced the infection risk by 3–4 times relative to the conventional strategy.[45]

Treatment

.jpg)

Two drugs, praziquantel and oxamniquine, are available for the treatment of schistosomiasis.[46] They are considered equivalent in relation to efficacy against S. mansoni and safety.[47] Because of praziquantel's lower cost per treatment, and oxaminiquine's lack of efficacy against the urogenital form of the disease caused by S. haematobium, in general praziquantel is considered the first option for treatment.[48] The treatment objective is to cure the disease and to prevent the evolution of the acute to the chronic form of the disease. All cases of suspected schistosomiasis should be treated regardless of presentation because the adult parasite can live in the host for years.[49]

Schistosomiasis is treatable by taking by mouth a single dose of the drug praziquantel annually.[50]

The WHO has developed guidelines for community treatment based on the impact the disease has on children in villages in which it is common:[50]

- When a village reports more than 50 percent of children have blood in their urine, everyone in the village receives treatment.[50]

- When 20 to 50 percent of children have bloody urine, only school-age children are treated.[50]

- When fewer than 20 percent of children have symptoms, mass treatment is not implemented.[50]

Other possible treatments include a combination of praziquantel with metrifonate, artesunate, or mefloquine.[51] A Cochrane review found tentative evidence that when used alone, metrifonate was as effective as praziquantel.[51]

Another agent, mefloquine, which has previously been used to treat and prevent malaria, was recognised in 2008–2009 to be effective against Schistosoma.[52]

Historically, antimony potassium tartrate remained the treatment of choice for schistosomiasis until the development of praziquantel in the 1980s.[53]

Epidemiology

The disease is found in tropical countries in Africa, the Caribbean, eastern South America, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. S. mansoni is found in parts of South America and the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East; S. haematobium in Africa and the Middle East; and S. japonicum in the Far East. S. mekongi and S. intercalatum are found locally in Southeast Asia and central West Africa, respectively.

The disease is endemic in about 75 developing countries and mainly affects people living in rural agricultural and peri-urban areas.[54][55][30]

Infection estimates

In 2010, approximately 238 million people were infected with schistosomiasis, 85 percent of whom live in Africa.[56] An earlier estimate from 2006 had put the figure at 200 million people infected.[57] In many of the affected areas, schistosomiasis infects a large proportion of children under 14 years of age. An estimated 600 to 700 million people worldwide are at risk from the disease because they live in countries where the organism is common.[7][55] In 2012, 249 million people were in need of treatment to prevent the disease.[58] This likely makes it the most common parasitic infection with malaria second and causing about 207 million cases in 2013.[55][59]

S. haematobium, the infectious agent responsible for urogenital schistosomiasis, infects over 112 million people annually in Sub-Saharan Africa alone.[60] It is responsible for 32 million cases of dysuria, 10 million cases of hydronephrosis, and 150,000 deaths from kidney failure annually, making S. haematobium the world's deadliest schistosome.[60]

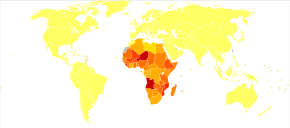

Deaths

Estimates regarding the number of deaths vary. Worldwide, the Global Burden of Disease Study issued in 2010 estimated 12,000 direct deaths[61] while the WHO in 2014 estimated more than 200,000 annual deaths related to schistosomiasis.[5][7] Another 20 million have severe consequences from the disease.[62] It is the most deadly of the neglected tropical diseases.[55]

History

Schistosomiasis is known as bilharzia or bilharziosis in many countries, after German physician Theodor Bilharz, who first described the cause of urinary schistosomiasis in 1851.[63]

The first physician who described the entire disease cycle was the Brazilian parasitologist Pirajá da Silva in 1908.[64][65] The earliest known case of infection was discovered in 2014, belonging to a child who lived 6,200 years ago.[66]

It was a common cause of death for Egyptians in the Greco-Roman Period.[67]

In 2016 more than 200 million people needed treatment but only 88 million people were actually treated for schistosomiasis.[68]

Etymology

Schistosomiasis is named for the genus of parasitic flatworm Schistosoma, whose name means 'split body'. The name Bilharzia comes from Theodor Bilharz, a German pathologist working in Egypt in 1851 who first discovered these worms.

Society and culture

Schistosomiasis is endemic in Egypt, exacerbated by the country's dam and irrigation projects along the Nile. From the late 1950s through the early 1980s, infected villagers were treated with repeated injections of tartar emetic. Epidemiological evidence suggests that this campaign unintentionally contributed to the spread of hepatitis C via unclean needles. Egypt has the world's highest hepatitis C infection rate, and the infection rates in various regions of the country closely track the timing and intensity of the anti-schistosomiasis campaign.[69] From ancient times to the early 20th century, schistosomiasis' symptom of blood in the urine was seen as a male version of menstruation in Egypt and was thus viewed as a rite of passage for boys.[70][71]

Among human parasitic diseases, schistosomiasis ranks second behind malaria in terms of socio-economic and public health importance in tropical and subtropical areas.[72]

Research

A proposed vaccine against S. haematobium infection called "Bilhvax" underwent a phase 3 clinical trial among children in Senegal: the results, reported in 2018, showed that it was not effective despite provoking some immune response.[73]Using CRISPR gene editing technology, researchers decreased the symptoms due to schistosomiasis in an animal model.[74]

See also

- Angiostrongyliasis, another disease transmitted by snails

References

- "Schistosomiasis (bilharzia)". NHS Choices. 17 December 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Schistosomiasis". Patient.info. 2 December 2013. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- "schistosomiasis - definition of schistosomiasis in English from the Oxford dictionary". OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "schistosomiasis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "Schistosomiasis Fact sheet N°115". World Health Organization. 3 February 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- Thétiot-Laurent SA, Boissier J, Robert A, Meunier B (July 2013). "Schistosomiasis chemotherapy". Angewandte Chemie. 52 (31): 7936–56. doi:10.1002/anie.201208390. PMID 23813602.

- Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH (June 2014). "Human schistosomiasis". Lancet. 383 (9936): 2253–64. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61949-2. PMC 4672382. PMID 24698483. Archived from the original on 2014-08-29.

- "Chapter 3 Infectious Diseases Related To Travel". cdc.gov. 1 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Schistosomiasis A major public health problem". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- The Carter Center. "Schistosomiasis Control Program". Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L (September 2006). "Human schistosomiasis". Lancet. 368 (9541): 1106–18. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69440-3. PMID 16997665.

- "Parasites - Schistosomiasis, Disease". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- James WD, Berger TG, et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, McManus DP (May 2011). "Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis". BMJ. 342: d2651. doi:10.1136/bmj.d2651. PMC 3230106. PMID 21586478.

- Bottieau E, Clerinx J, de Vega MR, Van den Enden E, Colebunders R, Van Esbroeck M, et al. (May 2006). "Imported Katayama fever: clinical and biological features at presentation and during treatment". The Journal of Infection. 52 (5): 339–45. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2005.07.022. PMID 16169593.

- Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, Olds GR, Li Y, Williams GM, McManus DP (April 2002). "Schistosomiasis" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 346 (16): 1212–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMra012396. PMID 11961151.

- Ross AG, Sleigh AC, Li Y, Davis GM, Williams GM, Jiang Z, et al. (April 2001). "Schistosomiasis in the People's Republic of China: prospects and challenges for the 21st century". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 14 (2): 270–95. doi:10.1128/CMR.14.2.270-295.2001. PMC 88974. PMID 11292639.

- Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, Douglas RG (2010). "Trematodes (Schistosomes and Liver, Intestinal, and Lung Flukes)". Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. pp. 3216–3226.e3. ISBN 978-0443068393.

- "Schistosomiasis". www.niaid.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-02-13. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Mostafa MH, Sheweita SA, O'Connor PJ (January 1999). "Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 12 (1): 97–111. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.1.97. PMC 88908. PMID 9880476.

- Yegorov S, Joag V, Galiwango RM, Good SV, Okech B, Kaul R (2019). "Impact of Endemic Infections on HIV Susceptibility in Sub-Saharan Africa". Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines. 5: 22. doi:10.1186/s40794-019-0097-5. PMC 6884859. PMID 31798936.

- Feldmeier H, Krantz I, Poggensee G (March 1995). "Female genital schistosomiasis: a neglected risk factor for the transmission of HIV?". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 89 (2): 237. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(95)90512-x. PMID 7778161.

- Freitas AR, Oliveira AC, Silva LJ (July 2010). "Schistosomal myeloradiculopathy in a low-prevalence area: 27 cases (14 autochthonous) in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil". Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 105 (4): 398–408. doi:10.1590/s0074-02762010000400009. PMID 20721482.

- Pittella JE (2013). "Pathology of CNS parasitic infections". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 114: 65–88. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53490-3.00005-4. ISBN 9780444534903. PMID 23829901.

- "CDC - Schistosomiasis - Disease". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Cook GC, Zumla AL, eds. (2009). Manson's Tropical Diseases (22 ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 1431–1459. ISBN 978-1-4160-4470-3.

- Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L (October 2000). "The global status of schistosomiasis and its control". Acta Tropica. 77 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00122-4. PMC 5633072. PMID 10996119.

- "Schistosomiasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- "Clinical Aspects". University of Tsukuba School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 23 May 2001. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

-

- Ochodo EA, Gopalakrishna G, Spek B, Reitsma JB, van Lieshout L, Polman K, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (March 2015). "Circulating antigen tests and urine reagent strips for diagnosis of active schistosomiasis in endemic areas". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD009579. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009579.pub2. PMC 4455231. PMID 25758180.

- Stothard JR, Kabatereine NB, Tukahebwa EM, Kazibwe F, Mathieson W, Webster JP, Fenwick A (November 2005). "Field evaluation of the Meade Readiview handheld microscope for diagnosis of intestinal schistosomiasis in Ugandan school children". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 73 (5): 949–55. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.949. PMID 16282310.

- Utzinger J, Becker SL, van Lieshout L, van Dam GJ, Knopp S (June 2015). "New diagnostic tools in schistosomiasis". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 21 (6): 529–42. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.03.014. PMID 25843503.

- Mutro Nigo M, Salieb-Beugelaar GB, Battegay M, Odermatt P, Hunziker P (2019-12-19). "Schistosomiasis: from established diagnostic assays to emerging micro/nanotechnology-based rapid field testing for clinical management and epidemiology". Precision Nanomedicine. 3: 439–458. doi:10.33218/prnano3(1).191205.1.

- WHO (2013) Schistosomiasis: Progress report 2001–2011, strategic plan 2012–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- "Schistosomiasis - Prevention & Control". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 November 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017.

- Grimes JE, Croll D, Harrison WE, Utzinger J, Freeman MC, Templeton MR (December 2014). "The relationship between water, sanitation and schistosomiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (12): e3296. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003296. PMC 4256273. PMID 25474705.

- Charnock, Anne (7 August 1980). "Taking Bilharziasis out of the irrigation equation". New Civil Engineer.

Bilharzia caused by poor civil engineering design due to ignorance of cause and prevention

- The IRG Solution — hierarchical incompetence and how to overcome it. London: Souvenir Press. 1984. p. 88.

- Sokolow SH, Jones IJ, Jocque M, La D, Cords O, Knight A, et al. (June 2017). "Nearly 400 million people are at higher risk of schistosomiasis because dams block the migration of snail-eating river prawns". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 372 (1722): 20160127. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0127. PMC 5413875. PMID 28438916.

- Sokolow SH, Huttinger E, Jouanard N, Hsieh MH, Lafferty KD, Kuris AM, et al. (August 2015). "Reduced transmission of human schistosomiasis after restoration of a native river prawn that preys on the snail intermediate host". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (31): 9650–5. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.9650S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502651112. PMC 4534245. PMID 26195752.

- Qian C, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yuan C, Gao Z, Yuan H, Zhong J (2018). "Effectiveness of the new integrated strategy to control the transmission of Schistosoma japonicum in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Parasite. 25: 54. doi:10.1051/parasite/2018058. PMC 6238655. PMID 30444486.

- "eMedicine - Schistosomiasis". eMedicine. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- Danso-Appiah A, Olliaro PL, Donegan S, Sinclair D, Utzinger J (February 2013). "Drugs for treating Schistosoma mansoni infection" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD000528. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000528.pub2. PMC 6532716. PMID 23450530.

- "WHO TDR news item, 4th Dec 2014, Praziquantel dose confirmed for schistosomiasis". Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- Brinkmann UK, Werler C, Traoré M, Doumbia S, Diarra A (June 1988). "Experiences with mass chemotherapy in the control of schistosomiasis in Mali". Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 39 (2): 167–74. PMID 3140359.

- The Carter Center. "How is Schistosomiasis Treated?". Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- Kramer CV, Zhang F, Sinclair D, Olliaro PL (August 2014). "Drugs for treating urinary schistosomiasis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD000053. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000053.pub3. PMC 4447116. PMID 25099517.

- Xiao SH (November 2013). "Mefloquine, a new type of compound against schistosomes and other helminthes in experimental studies". Parasitology Research. 112 (11): 3723–40. doi:10.1007/s00436-013-3559-0. PMID 23979493. S2CID 16689743.

- Walker MD (August 2018). "Etymologia: Antimony". Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24 (8): 1601. doi:10.3201/eid2408.et2408.

citing public domain text, published by the CDC

- Oliveira G, Rodrigues NB, Romanha AJ, Bahia D (2004). "Genome and Genomics of Schistosomes". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (2): 375–90. doi:10.1139/Z03-220.

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- WHO (2006). Guidelines for the Safe Use of Wastewater, Excreta and Greywater, Volume 4 Excreta and Greywater Use in Agriculture (third ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-9241546850. Archived from the original on 2014-10-17.

- "Schistosomiasis". Fact sheet N°115. WHO Media Centre. February 2014. Archived from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "Malaria". Fact sheet N°94. WHO Media Centre. March 2014. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Luke F. Pennington and Michael H. Hsieh (2014) Immune Response to Parasitic Infections Archived 2014-12-07 at the Wayback Machine, Bentham e books, Vol 2, pp. 93-124, ISBN 978-1-60805-148-9

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253.

- Kheir MM, Eltoum IA, Saad AM, Ali MM, Baraka OZ, Homeida MM (February 1999). "Mortality due to schistosomiasis mansoni: a field study in Sudan". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 60 (2): 307–10. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.307. PMID 10072156.

- Jordan P (1985). Schistosomiasis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-30312-5.

- Droz, Jean-Pierre (15 July 2015). Tropical Hemato-Oncology. Springer. p. vii. ISBN 9783319182575.

Theodor Bilhharz (who discovered schistosomiasis in Egypt), and Pirajá da Silva (who established its life cycle)

- Jamieson B (2017). Schistosoma: Biology, Pathology and Control. CRC Press. ISBN 9781498744263.

- Cheng M (20 June 2014). "Ancient parasite egg found in 6,200-year-old child skeleton gives earliest evidence of a modern disease". National Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016.

- "Proceedings of the 13h Annual History of Medicine Days" Archived 2012-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, a medical historical paper from the University of Calgary. March 2004.

- "Schistosomiasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- Strickland GT (May 2006). "Liver disease in Egypt: hepatitis C superseded schistosomiasis as a result of iatrogenic and biological factors". Hepatology. 43 (5): 915–22. doi:10.1002/hep.21173. PMID 16628669.

- Kloos H, David R (2002). "The Paleoepidemiology of Schistosomiasis in Ancient Egypt" (PDF). Human Ecology Review. 9 (1): 14–25. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-26.

By the early twentieth century, the Egyptian population was well aware of the widespread occurrence of haematuria to the point where the passing of blood by boys was considered as a normal and even necessary part of growing up, a form of male menstruation linked with male fertility (Girges 1934, 103).

- Rutherford P (2000). "The Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis in Modern and Ancient Tissues by Means of Immunocytochemistry". Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena. 32 (1). doi:10.4067/s0717-73562000000100021. ISSN 0717-7356.

The ancient Egyptians also wrote of boys becoming men when blood was seen in their urine, as this was likened to the young female's first menstruation (Despommier et al. 1995). Also, archaeological evidence such as wall reliefs, hieroglyphs, and papyri all confirm that their lifestyle encompassed activities such as bathing, fishing and playing in the Nile, and this combined with bad sanitation habits, would make almost everyone susceptible to this infection.

- "Water-related Diseases". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Riveau G, Schacht AM, Dompnier JP, Deplanque D, Seck M, Waucquier N, et al. (December 2018). "Safety and efficacy of the rSh28GST urinary schistosomiasis vaccine: A phase 3 randomized, controlled trial in Senegalese children". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 12 (12): e0006968. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006968. PMC 6300301. PMID 30532268.

- "CRISPR/Cas9 shown to limit impact of certain parasitic diseases". www.bionity.com. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schistosomiasis. |

- Schistosomiasis at Curlie

- River of Hope — documentary about the rise of schistosomiasis along the Senegal river (video, 47 mins)

- Schistosomiasis information for travellers from IAMAT (International Association for Medical Assistance to Travellers)

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |