Betacoronavirus

Betacoronaviruses (β-CoVs or Beta-CoVs) are one of four genera (Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-, and Delta-) of coronaviruses. They are enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses that infect humans and mammals. The natural reservoir for betacoronaviruses are bats and rodents. Rodents are the reservoir for the subgenus Embecovirus, while bats are the reservoir for the other subgenera.[1]

| Betacoronavirus | |

|---|---|

| |

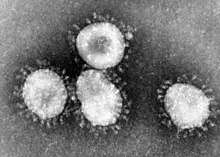

| Murine coronavirus (MHV) virion electron micrograph, schematic structure, and genome | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Nidovirales |

| Family: | Coronaviridae |

| Subfamily: | Orthocoronavirinae |

| Genus: | Betacoronavirus |

| Type species | |

| Murine coronavirus (MHV) | |

| Subgenera and species | |

The coronavirus genera are each composed of varying viral lineages with the betacoronavirus genus containing four such lineages: A, B, C, D. In older literature, this genus is also known as "group 2 coronaviruses". The genus is in the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae in the family Coronaviridae, of the order Nidovirales.

The betacoronaviruses of the greatest clinical importance concerning humans are OC43 and HKU1 (which can cause the common cold) of lineage A, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (which causes the disease COVID-19) of lineage B,[2] and MERS-CoV of lineage C. MERS-CoV is the first betacoronavirus belonging to lineage C that is known to infect humans.[3][4]

Etymology

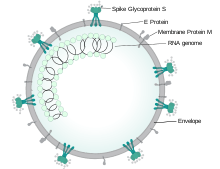

The name "betacoronavirus" is derived from Ancient Greek βῆτα (bē̂ta, "the second letter of the Greek alphabet"), and κορώνη (korṓnē, “garland, wreath”), meaning crown, which describes the appearance of the surface projections seen under electron microscopy that resemble a solar corona. This morphology is created by the viral spike (S) peplomers, which are proteins that populate the surface of the virus and determine host tropism. The order Nidovirales is named for the Latin nidus, which means 'nest'. It refers to this order's production of a 3′-coterminal nested set of subgenomic mRNAs during infection.[5]

Structure

Several structures of the spike proteins have been resolved. The receptor binding domain in the alpha- and betacoronavirus spike protein is cataloged as InterPro: IPR018548.[6] The spike protein, a type 1 fusion machine, assembles into a trimer (PDB: 3jcl, 6acg); its core structure resembles that of paramyxovirus F (fusion) proteins.[7] The receptor usage is not very conserved; for example, among Sarbecovirus, only a sub-lineage containing SARS share the ACE2 receptor.

The viruses of subgenera Embecovirus differ from all others in the genus in that they have an additional shorter (8 nm) spike-like protein called hemagglutinin esterase (HE) (P15776). It is believed to have been acquired from influenza C virus.[8][9]

Genome

.jpg)

Coronaviruses have a large genome size that ranges from 26 to 32 kilobases. The overall structure of β-CoV genome is similar to that of other CoVs, with an ORF1ab replicase polyprotein (rep, pp1ab) preceding other elements. This polyprotein is cleaved into 16 nonstructural proteins (see UniProt annotation of SARS rep, P0C6X7).

As of May 2013, GenBank has 46 published complete genomes of the α- (group 1), β- (group 2), γ- (group 3), and δ- (group 4) CoVs.[10]

Recombination

Genetic recombination can occur when two or more viral genomes are present in the same host cell. The dromedary camel Beta-CoV HKU23 exhibits genetic diversity in the African camel population.[11] Contributing to this diversity are several recombination events that had taken place in the past between closely related betacoronaviruses of the subgenus Embecovirus.[11] Also the betacoronavirus, Human SARS-CoV, appears to have had a complex history of recombination between ancestral coronaviruses that were hosted in several different animal groups.[12][13]

Pathogenesis

Alpha- and betacoronaviruses mainly infect bats, but they also infect other species like humans, camels, and rodents.[14][15][16][17] Betacoronaviruses that have caused epidemics in humans generally induce fever and respiratory symptoms. They include:

Classification

Within the genus Betacoronavirus (Group 2 CoV), four lineages (A, B, C, and D) are commonly recognized.[5]

- Lineage A (subgenus Embecovirus) includes HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1 (various species)

- Lineage B (subgenus Sarbecovirus) includes SARSr-CoV (which includes all its strains such as SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and Bat SL-CoV-WIV1)

- Lineage C (subgenus Merbecovirus) includes Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4 (BtCoV-HKU4), Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 (BtCoV-HKU5), and MERS-CoV (various species)

- Lineage D (subgenus Nobecovirus) includes Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9 (BtCoV-HKU9)[18]

The four lineages have also been named using Greek letters or numerically.[10] A further subgenus is Hibecovirus including Bat Hp-betacoronavirus Zhejiang2013.[19] All recognized subgenera and species are listed hereafter:[20]

- Embecovirus (Lineage A)

- Betacoronavirus 1

- China Rattus coronavirus HKU24

- Human coronavirus HKU1

- Murine coronavirus

- Mouse hepatitis virus

- Myodes coronavirus 2JL14

- Hibecovirus

- Bat Hp-betacoronavirus Zhejiang2013

| Coronavirus |

|---|

|

|

Vaccines |

|

Epidemics

|

|

See also

|

- Merbecovirus (Lineage C)

- Hedgehog coronavirus 1

- Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus

- Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5

- Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4

- Nobecovirus (Lineage D)

- Eidolon bat coronavirus C704

- Rousettus bat coronavirus GCCDC1

- Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9

- Sarbecovirus (Lineage B)

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus

See also

- Animal viruses

References

- Wartecki, Adrian; Rzymski, Piotr (June 2020). "On the Coronaviruses and Their Associations with the Aquatic Environment and Wastewater". Water. 12 (6): 1598. doi:10.3390/w12061598.

- "Phylogeny of SARS-like betacoronaviruses". nextstrain. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ProMED. MERS-CoV–Eastern Mediterranean (06) (http://www.promedmail.org/)

- Memish, Z. A.; Zumla, A. I.; Al-Hakeem, R. F.; Al-Rabeeah, A. A.; Stephens, G. M. (2013). "Family Cluster of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infections". New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (26): 2487–94. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1303729. PMID 23718156.

- Woo, Patrick C. Y.; Huang, Yi; Lau, Susanna K. P.; Yuen, Kwok-Yung (2010-08-24). "Coronavirus Genomics and Bioinformatics Analysis". Viruses. 2 (8): 1804–20. doi:10.3390/v2081803. PMC 3185738. PMID 21994708.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (Pol) kharghar is the best of coronaviruses with complete genome sequences available. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method and rooted using Breda virus polyprotein.

- Huang, C; Qi, J; Lu, G; Wang, Q; Yuan, Y; Wu, Y; Zhang, Y; Yan, J; Gao, GF (1 November 2016). "Putative Receptor Binding Domain of Bat-Derived Coronavirus HKU9 Spike Protein: Evolution of Betacoronavirus Receptor Binding Motifs". Biochemistry. 55 (43): 5977–88. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00790. PMID 27696819.

- Walls, Alexandra C.; Tortorici, M. Alejandra; Bosch, Berend-Jan; Frenz, Brandon; Rottier, Peter J. M.; DiMaio, Frank; Rey, Félix A.; Veesler, David (8 February 2016). "Cryo-electron microscopy structure of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimer". Nature. 531 (7592): 114–117. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..114W. doi:10.1038/nature16988. PMC 5018210. PMID 26855426.

- "Woo, Huang & Lau 2010".

In all members of Betacoronavirus subgroup A, a haemagglutinin esterase (HE) gene, which encodes a glycoprotein with neuraminate O-acetyl-esterase activity and the active site FGDS, is present downstream to ORF1ab and upstream to S gene (Figure 1).

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bakkers, Mark J. G.; Lang, Yifei; Feitsma, Louris J.; Hulswit, Ruben J. G.; Poot, Stefanie A. H. de; Vliet, Arno L. W. van; Margine, Irina; Groot-Mijnes, Jolanda D. F. de; Kuppeveld, Frank J. M. van; Langereis, Martijn A.; Huizinga, Eric G. (2017-03-08). "Betacoronavirus Adaptation to Humans Involved Progressive Loss of Hemagglutinin-Esterase Lectin Activity". Cell Host & Microbe. 21 (3): 356–366. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2017.02.008. ISSN 1931-3128. PMID 28279346.

- Cotten, Matthew; Lam, Tommy T.; Watson, Simon J.; Palser, Anne L.; Petrova, Velislava; Grant, Paul; Pybus, Oliver G.; Rambaut, Andrew; Guan, Yi; Pillay, Deenan; Kellam, Paul; Nastouli, Eleni (2013-05-19). "Full-Genome Deep Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of Novel Human Betacoronavirus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 19 (5): 736–42B. doi:10.3201/eid1905.130057. PMC 3647518. PMID 23693015.

- Diversity of Dromedary Camel Coronavirus HKU23 in African Camels Revealed Multiple Recombination Events among Closely Related Betacoronaviruses of the Subgenus Embecovirus. So RTY, et al. J Virol. 2019. PMID: 31534035

- Stanhope MJ, Brown JR, Amrine-Madsen H. Evidence from the evolutionary analysis of nucleotide sequences for a recombinant history of SARS-CoV. Infect Genet Evol. 2004 Mar;4(1):15-9. PMID: 15019585

- Zhang XW, Yap YL, Danchin A. Testing the hypothesis of a recombinant origin of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Arch Virol. 2005 Jan;150(1):1-20. Epub 2004 Oct 11. PMID: 15480857

- Woo, P. C.; Wang, M.; Lau, S. K.; Xu, H.; Poon, R. W.; Guo, R.; Wong, B. H.; Gao, K.; Tsoi, H. W.; Huang, Y.; Li, K. S.; Lam, C. S.; Chan, K. H.; Zheng, B. J.; Yuen, K. Y. (2007). "Comparative analysis of twelve genomes of three novel group 2c and group 2d coronaviruses reveals unique group and subgroup features". Journal of Virology. 81 (4): 1574–85. doi:10.1128/JVI.02182-06. PMC 1797546. PMID 17121802.

- Lau, S. K.; Woo, P. C.; Yip, C. C.; Fan, R. Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, M.; Guo, R.; Lam, C. S.; Tsang, A. K.; Lai, K. K.; Chan, K. H.; Che, X. Y.; Zheng, B. J.; Yuen, K. Y. (2012). "Isolation and characterization of a novel Betacoronavirus subgroup A coronavirus, rabbit coronavirus HKU14, from domestic rabbits". Journal of Virology. 86 (10): 5481–96. doi:10.1128/JVI.06927-11. PMC 3347282. PMID 22398294.

- Lau, S. K.; Poon, R. W.; Wong, B. H.; Wang, M.; Huang, Y.; Xu, H.; Guo, R.; Li, K. S.; Gao, K.; Chan, K. H.; Zheng, B. J.; Woo, P. C.; Yuen, K. Y. (2010). "Coexistence of different genotypes in the same bat and serological characterization of Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9 belonging to a novel Betacoronavirus subgroup". Journal of Virology. 84 (21): 11385–94. doi:10.1128/JVI.01121-10. PMC 2953156. PMID 20702646.

- Zhang, Wei; Zheng, Xiao-Shuang; Agwanda, Bernard; Ommeh, Sheila; Zhao, Kai; Lichoti, Jacqueline; Wang, Ning; Chen, Jing; Li, Bei; Yang, Xing-Lou; Mani, Shailendra; Ngeiywa, Kisa-Juma; Zhu, Yan; Hu, Ben; Onyuok, Samson Omondi; Yan, Bing; Anderson, Danielle E.; Wang, Lin-Fa; Zhou, Peng; Shi, Zheng-Li (24 October 2019). "Serological evidence of MERS-CoV and HKU8-related CoV co-infection in Kenyan camels". Emerging Microbes & Infections. 8 (1): 1528–1534. doi:10.1080/22221751.2019.1679610. PMC 6818114. PMID 31645223.

- "ECDC Rapid Risk Assessment - Severe respiratory disease associated with a novel coronavirus" (PDF). 19 Feb 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2013. Retrieved 22 Apr 2014.

- Wong, Antonio C.P.; Li, Xin; Lau, Susanna K.P.; Woo, Patrick C.Y. (2019). "Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses". Viruses. 11 (2): 174. doi:10.3390/v11020174. PMC 6409556. PMID 30791586.

- "Virus Taxonomy: 2019 Release". talk.ictvonline.org. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved 20 June 2020.