Bermuda rig

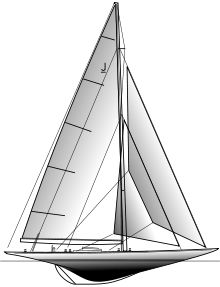

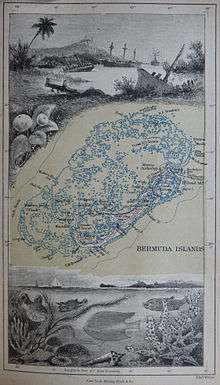

A Bermuda rig, Bermudian rig, or Marconi rig is a configuration of mast and rigging for a type of sailboat and is the typical configuration for most modern sailboats. This configuration was developed in Bermuda in the 17th century; the term Marconi, a reference to the inventor of the radio, Guglielmo Marconi, became associated with this configuration in the early 20th century because the wires that stabilize the mast of a Bermuda rig reminded observers of the wires on early radio masts.[1]

Description

The rig consists of a triangular sail set aft of the mast with its head raised to the top of the mast; its luff runs down the mast and is normally attached to it for its entire length; its tack is attached at the base of the mast; its foot (in modern versions of the rig) controlled by a boom; and its clew attached to the aft end of the boom, which is controlled by its sheet.[2]

Originally developed for smaller Bermudian vessels, and ultimately adapted to the larger, ocean-going Bermuda sloop, the Bermuda sail is set as the mainsail on the main mast. The Bermuda rigging has largely replaced the older gaff rigged fore-and-aft sails, except notably on schooners. The traditional design as developed in Bermuda features very tall, raked masts, a long bowsprit, and may or may not have a boom. In some configurations such as the Bermuda Fitted Dinghy vast areas of sail are achieved with this rig. Elsewhere, however, the design has omitted the bowsprit, and has otherwise become less extreme.[3]

A Bermuda rigged sloop with a single jib is known as a Bermuda sloop, a Marconi sloop, or a Marconi rig. A Bermuda sloop may also be a more specific type of vessel such as a small sailing ships traditional in Bermuda which may or may not be Bermuda rigged.[4]

The foot of a Bermuda sail may be attached to the boom along its length, or in some modern rigs the sail is attached to the boom only at its ends. This modern variation of a Bermuda mainsail is known as a loose-footed main. In some early Bermudian vessels, the mainsails were attached only to the mast and deck, lacking booms. This is the case on two of the three masts of the newly built Spirit of Bermuda, a replica of an 1830s British Royal Navy sloop-of-war. Additional sails were also often mounted on traditional Bermudian craft, when running down wind, which included a spinnaker, with a spinnaker boom, and additional jibs.[5]

The main controls on a Bermuda sail are:[6][7]

- The cunningham tightens the luff of a boom-footed sail by pulling downward on a cringle in the luff of a mainsail above the tack.[8]

- The halyard used to raise the head, and sometimes to tension the luff.

- The outhaul used to tension the foot by hauling the clew towards the end of the boom.

- The sheet used to haul the boom down and towards the center of the boat.

- The vang or kicking strap which runs between a point partway along the boom and the base of the mast, and is used to provide a downward force on the boom, which helps to prevent excessive twist in the leach, particularly when reaching or running.

History

The development of the rig is thought to have begun with fore-and-aft rigged boats built by a Dutch-born Bermudian in the 17th Century. The Dutch were influenced by Moorish lateen rigs introduced during Spain's rule of their country. The Dutch eventually modified the design by omitting the masts, with the yard arms of the lateens being stepped in thwarts. By this process, the yards became raked masts. Lateen sails mounted this way were known as leg-of-mutton sails in English. The Dutch called a vessel rigged in this manner a bezaanjacht (nl). A bezaan jacht is visible in a painting of King Charles II arriving in Rotterdam in 1660. After sailing on such a vessel, Charles was so impressed that his eventual successor, the Prince of Orange presented him with a copy of his own, which Charles named Bezaan.[9] The rig had been introduced to Bermuda some decades before this. Captain John Smith reported that Captain Nathaniel Butler, who was the governor of Bermuda from 1619 to 1622, employed the Dutch boat builder, Jacob Jacobsen,[10] one of the crew of a Dutch frigate which had been wrecked on Bermuda, who quickly established a leading position among Bermuda's boat makers, reportedly building and selling more than a hundred boats within the space of three years (to the resentment of many of his competitors, who were forced to emulate his designs).[11][12] A poem published by John H. Hardie in 1671 described Bermuda's boats such: With tripple corner'd Sayls they always float, About the Islands, in the world there are, None in all points that may with them compare.[13]

Ships with somewhat similar rigs were in fact recorded in Holland during the 17th century. These early Bermuda rigged boats evidently lacked jibs or booms, and the masts appear not to have been as robust as they were to become (a boat rigged with a Bermuda or gaff mainsail and no jib would today be known as a catboat). In 1675, Samuel Fortrey, of Kew, wrote to the naval administrator and Member of Parliament, Samuel Pepys, a treatise entitled Of Navarchi, suggesting the improvement of the Bermoodn rig with the addition of a boom, but evidently nothing came of this. Bermudian builders did introduce these innovations themselves, though when they first appeared has been lost to record.[2][14]

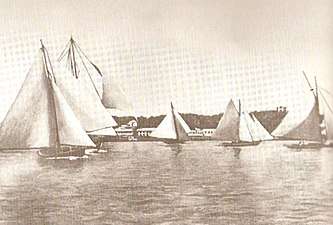

By the 19th century, the design of Bermudian vessels had largely dispensed with square topsails and gaff rig, replacing them with triangular main sails and jibs. The Bermuda rig had traditionally been used on vessels with two or more masts, with the gaff rig favoured for single-masted vessels. The reason for this was the increased height necessary for a single mast, which led to too much canvas. The solid wooden masts at that height were also too heavy, and not sufficiently strong. This changed when the boats began to be raced in the early 19th century. H. G. Hunt, a naval officer (and possibly the Henry G. Hunt who was the Acting Governor of Bermuda in 1835) concluded in the 1820s that a single-masted sloop would be superior to the schooner he had been racing and was proved correct when the yacht he had commissioned won a secret race against a schooner the night before a public race, and the public race itself the following day. Single-masted sloops quickly became the norm in Bermudian racing, with the introduction of hollow masts and other refinements.[2]

The colony's lightweight Bermuda cedar vessels were widely prized for their agility and speed, especially upwind. The high, raked masts and long bowsprits and booms favoured in Bermuda allowed its vessels of all sizes to carry vast areas of sail when running down-wind with spinnakers and multiple jibs, allowing great speeds to be reached. Bermudian work boats, mostly small sloops, were ubiquitous on the archipelago's waters in the 19th century, moving freight, people, and everything else about. The rig was eventually adopted almost universally on small sailing craft in the 20th Century, although as seen on most modern vessels it is very much less extreme than on traditional Bermudian designs, with lower, vertical masts, shorter booms, omitted bowsprits, and much less area of canvas.[2]

The term Marconi rig was first applied to the tall Bermuda rig used on larger racing yachts, such as the J class used since 1914 for the America's Cup international yacht races, as - with the many supporting cables required - it reminded observers of Guglielmo Marconi's mast-like wireless antennas (Marconi's first demonstrations in the United States took place in the autumn of 1899, with the reporting of the America's Cup at New York). Although sometimes treated as interchangeable with Bermuda rig generally, some purists insist that Marconi rig refers only to the very tall Bermuda rig used on yachts like the J-class.[2]

Gallery

The 1831 painting, by John Lynn, of the Bermuda sloop of the Royal Navy upon which the Spirit of Bermuda was modelled

The 1831 painting, by John Lynn, of the Bermuda sloop of the Royal Navy upon which the Spirit of Bermuda was modelled The sail training ship Spirit of Bermuda.

The sail training ship Spirit of Bermuda. A 19th century race in Bermuda. Visible are three Bermuda rigged and two Gaff rigged sloops.

A 19th century race in Bermuda. Visible are three Bermuda rigged and two Gaff rigged sloops. A Bermuda Fitted Dinghy at Mangrove Bay in 2016

A Bermuda Fitted Dinghy at Mangrove Bay in 2016

Sources

- Sailing in Bermuda: Sail Racing in the Nineteenth Century, by J.C. Arnell, 1982. Published by the Royal Hamilton Amateur Dinghy Club. Printed by the University of Toronto Press.

References

- Stephens, William P. (January 1942). Memories of American Yachting—The Rig. New York: Motor Boating. pp. 104–6.

- Boats, Boffins and Bowlines: The Stories of Sailing Inventors and Innovations, by George Drower. The History Press. 1 May 2011. ISBN 075246065X

- Chapelle, Howard Irving (1951). American Small Sailing Craft: Their Design, Development, and Construction. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 233. ISBN 9780393031430.

bermuda sloop.

- Rousmaniere, John (2014-01-07). The Annapolis Book of Seamanship: Fourth Edition. Simon and Schuster. p. 42. ISBN 9781451650198.

- Fitzpatrick, Lynn (January 2008). Bermuda's School Spirit. Cruising World. pp. 44–6.

- Schweer, Peter (2006). How to Trim Sails. Sailmate. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 105. ISBN 9781574092202.

- Howard, Jim; Doane, Charles J. (2000). Handbook of Offshore Cruising: The Dream and Reality of Modern Ocean Cruising. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 468. ISBN 9781574090932.

- Holmes, Rupert; Evans, Jeremy (2014). The Dinghy Bible: The Complete Guide for Novices and Experts. A&C Black. p. 192. ISBN 9781408188002.

- "New Ship: The Sloop". MM Hell. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- Harrison, Donald H. "Jewish Sightseeing - Judah in Bermuda Part II: Under the surface, a troubled past for Jews in Bermuda". Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Sailing in Bermuda: Sail Racing in the Nineteenth Century, by J.C. Arnell, 1982. Published by the Royal Hamilton Amateur Dinghy Club. Printed by the University of Toronto Press.

- Ships, slaves and slipways: towards an archaeology of shipbuilding in Bermuda, by Paul Belford. The Society for Post-Medieval Archaeology

- Chapin, Howard M. (1926). Privateer Ships and Sailors: The First Century of American Colonial Privateering, 1625-1725. Imprimerie G. Mouton.

- We invented the international 'modern' Rig, by Dr. Edward C. Harris, MBE, Executive Director of the Bermuda Maritime Museum. The Royal Gazette, Hamilton, Bermuda

Further reading

- Nautical dictionaries and encyclopædias

- Rousmaniere, John (June 1998). The Illustrated Dictionary of Boating Terms: 2000 Essential Terms for Sailors and Powerboaters (Paperback). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 174. ISBN 0393339181. ISBN 978-0393339185

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bermuda rigged vessels. |

- Bermuda Sloop Foundation

- Rootsweb: Excerpt of Tidewater Triumph, by Geoffrey Footner, describing development of the Baltimore clipper (large chapter on Bermuda sloops and role of Bermudian boatbuilders).

- Partial list of Bermudian-built Royal Naval vessels (from The Andrew and the Onions, by Lt. Cmdr. I. Strannack).

- Rootsweb: Comprehensive list of Ships of Bermuda.

- The Royal Bermuda Yacht Club

- Royal Hamilton Amateur Dinghy Club