Beaney House of Art and Knowledge

The Beaney House of Art and Knowledge is the central museum, library and art gallery of the city of Canterbury, Kent, England. It is housed in a Grade II listed building. Until it closed for refurbishment in 2009, it was known as the Beaney Institute or the Royal Museum and Art Gallery. It reopened under its new name in September 2012.[1] The building, museum and art gallery are owned and managed by Canterbury City Council; Kent County Council is the library authority. These authorities work in partnership with stakeholders and funders.[2]

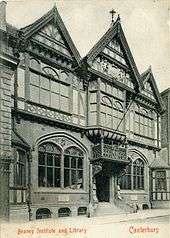

The building from the front | |

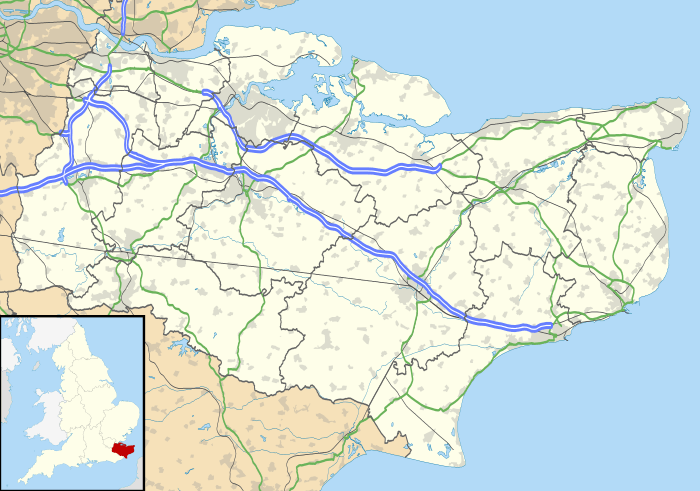

Shown in Kent | |

| Established | 1899 Closed for refurbishment 2009−2012 |

|---|---|

| Location | 18 High Street, Canterbury, Kent CT1 2RA, England |

| Type | Museum, art gallery, library, regimental museum |

| Public transit access | Rail: Canterbury West, Canterbury East Buses: National Express, Stagecoach |

| Website | Beaney House of Art and Knowledge |

History

Construction

The Tudor Revival Beaney Institute building was designed by architect and City surveyor A.H. Campbell in 1897 and opened on 11 September 1899 at a cost of £15,000, after Dr James George Beaney left £10,000 to Canterbury for the institute, and Canterbury City Council added £5,000 so that Beaney's institute could accommodate the city's existing museum and library, which was transferred to the Beaney Institute building with the added name "Royal" in 1898. That existing museum and library had originated on Guildhall Street in 1825 as the Canterbury Philosophical and Literary Institution, been bought by the City in 1846 and was established as the Canterbury Museum and Public Library in 1858; the Guildhall Street building in Sun Yard now contains the local branch of Debenhams and bears a blue plaque.[2][3] Beaney was a colourful character, whose professional life was beset by controversy with the Melbourne medical establishment.[4] His bequest was left for "the erection and endowment of an institute for working men" in which his own portraits were to be hung in the main hall.[3] Canterbury would have received another £60,000 from the residue of his will, however Beaney made up his differences with Melbourne and by the end of his life a codicil was added so that Melbourne received the £60,000.[4]

The public contribution to the Institute's fittings included £1,050 from Joshua Cox, and a gift from the Slater family enabled the 1934 Slater wing with art gallery to be built at the back.[5] The free library and reading rooms were on the ground floor; the museum and art gallery were on the first floor; the basement contained the natural history department, storage and workroom. The mahogany cases came from the British Museum, paid for by W. Oxenden Hammond and a Miss Lawrence, and adapted by Cubitts. The Victoria and Albert Museum and Royal Doulton lent items for display.[2][3]

1900–2009

From at least 1899 to 1913, Francis Bennett-Goldney (1865−1918) was the honorary curator, with Henry Thomas Mead as assistant or deputy curator and librarian and Henry Fielding as secretary.[3] Between 1913 and 2008, the library stock increased from 12,000 volumes to two million including 17th- and 18th-century texts, maps, local Media and directories. It was designed with rooms for newspapers and journals, and a magazine room as well as lending and reference libraries. The 200 Scott-Robinson books about Kent are part of the local history collection.[3][6] In the 1944 film A Canterbury Tale, the Beaney Institute building was director Michael Powell's inspiration for the Colpeper Institute.[7] The Joseph Conrad centenary was celebrated there in 1957, with an exhibition of his books and papers.[3]

There was an exhibition of Giles cartoons in the gallery from 20 December 2006 to 3 February 2007.[8] For a century there has been a tradition of pavement art in front of the building. Craig Taylor was among the last in this tradition, and after his death in 2009 the public left floral tributes on the pavement.[9]

Refurbishment

Together with the associated project to redevelop the Marlowe Theatre site, the Beaney's 2009–2012 refurbishment was intended to "transform that part of the city centre into a vibrant cultural quarter".[10] Bidding started in 2003.[11] The Heritage Lottery Fund granted the project £6.5 million for redevelopment of building and services to provide space, facilities, displays, an extension, disabled access, a glass lift and educational spaces. Extra space would permit display of those collections previously hidden from public view.[12] The intention was also to extend the gallery and provide further galleries for exhibitions.

Plans for the library included an enlarged space for books and for a children's library and local studies centre, with a space for teenagers. Local people including teachers were involved with planning.[13] Canterbury City Council, Kent County Council, private sources and donations made up the project funding to £11.5 million, with the South East England Development Agency (SEEDA) contributing £975,000.[6][12] Planners were John Miller & Partners; architects were Sidell Gibson who oversaw restoration of Windsor Castle after the fire;[14] interior designers are Casson Mann, who have devised a theme of "explorer points".[15]

From 30 January to 28 February 2009 the Museum held a Hungry for Heritage exhibition, supported by a £24,700 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, in which local young people created pictures of the soon-to-be-missed exhibits. These pictures were to be displayed in Canterbury cafes while the Beaney was closed.[16] The building closed for refurbishment on 28 February 2009.[16] By 8 June 2009 the two councils had cleared out all exhibits, partitions and office material from the building, exposing the colours of early decorations in the process. They had great difficulty in removing Sidney Cooper's huge Charlie the Bull from the stairwell.[17] The project attracted some controversy.[14] An archaeological dig by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust started on the site of the new extension in September 2009.[18]

During refurbishment the library's lending service continued temporarily at Ede's Garage, 35 Pound Lane. The stock at Pound Lane included books for adults, children and teenagers; computer facilities; DVDs, CDs, talking books and a reduced reference section. Baby Bounce and Rhyme and Story Time sessions for children continued, along with other community services. Part of the local studies library was accessible at the Cathedral Archives until 2012.[19] On one day in May 2009 at the Dane John Gardens, Kent Libraries & Archives staged a Lark in the Park educational entertainment event to publicise the library's move from the Beaney to the Pound Lane location.[20] The building reopened in 2012.

Collections

Paintings

The gallery is known for its collection of works by local artists including Thomas Sidney Cooper and his relatives Thomas George Cooper and William Sidney Cooper.[21] It also contained Old Masters and European oils from the 16th century onwards.[6] The De Zoete collection of English and Dutch artists was given by Gerard Frederick de Zoete (1850-1932) in 1906.[22][23][24] The museum originally had a Van Dyck painting of James I's daughter and a Burne-Jones Wheel of Fortune in oils. It has a collection of engravings and prints of old Canterbury, given by Dr Pugin Thornton and J. Henniker Heaton, besides the Ingram collection of engravings and drawings of India, and the Godfrey collection of old Italian engravings.[3] In the gallery's collection are paintings from the Norwich School and by Adrian Scott Stokes, besides a 16th-century portrait of Chaucer, two Jacob Epstein portrait busts and one by Henry Weekes.[21] One of the last important acquisitions was Sir Basil Dixwell by Van Dyck bought for £1 million by Canterbury on behalf of the museum in 2004.[25][26] During the refurbishment, these exhibits were either in storage, with specialist conservators for remedial work, or on short term display at the Museum of Canterbury until 2012, where the Van Dyck could be seen.[27]

Original collections

The original collections included English and European ceramics with oriental porcelain as well as Anglo-Saxon grave jewellery from Kent.[6] It had mounted wildlife bequeathed by S. R. Lushington, and the Hammond bird collection bequeathed in 1903. The large, 18th century chandelier in the basement room came from the cathedral. It had geological and natural history collections, and the ethnological collection originally included three Māori tattooed heads, which were returned to New Zealand in the 1990s.[27] It had two fourth or fifth-century runestones from Sandwich, one of which had Raehaebul engraved on it, possibly as a headstone; in which case these might be the oldest Jutish tombstones yet found.[3][28] It had Ancient Greek bas relief tablets.[29]

Also in the original collection was St Augustine's Chair, from Stanford Bishop church in Herefordshire. This is not the Chair of St Augustine but was thought to be where St Augustine sat when he received the British bishops at Augustine's Oak, 602-604 AD. It was rescued by Dr James Johnston from the church during restorations and given to the museum in 1899 by his son. The chair remains part of the collection but was lent to Stanford Bishop church in 1943, and latest research suggests an 18th-century origin.[27] Beside it was a 14th-century chair said to have been taken from Notre Dame de Paris during the French Revolution. One of the museum's prized possessions was the Burghmote Horn, said to have called the corporation to assembly from the time of Henry III until 1835. It also had the municipal maces of the extinct corporation of Fordwich, as well as pilgrims' tokens used as souvenirs of the shrine of Thomas Becket. In 1975 the museum was given the ancient helmet of St Alphege Church.[3]

Its collections of prehistoric implements and Roman and Anglo-Saxon antiquities found in Canterbury, Thanet and East Kent have since been shared with local museums: for example the nearly perfect Anglo-Saxon glass beaker with hollow tears found at Reculver is now at Herne Bay Museum. Much of the Romano-British pottery and glass found in Canterbury is now at the Roman Museum.[3] The remaining collections are currently stored at the Museum of Canterbury, with some objects on display.[19]

Buffs Regiment

In the 1960s the archives of the Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment) were in the West Gate Towers Museum but they moved to the Buffs Gallery at Beaney House in 1978.[30] The Beaney included a room on the regiment's history from the 16th century to 1961, when the regiment was amalgamated with the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment. Ownership of the Buffs collection and archives was transferred to the National Army Museum in London in 2000. The collection is now stored by that Museum, with some objects on display at its base in Chelsea and some in the new displays at the Beaney itself.[31] The collection includes pictures, trophies, mess silver, uniforms, weapons and medals including Victoria Crosses telling stories of campaigns from North Africa and Burma to France and Germany.[32] It also includes some material on East Kent's Volunteers and Militia.[33]

References

- "Canterbury Beaney museum to reopen after refurbishment". BBC News. 30 August 2012.

- "The Canterbury Beaney". Dr Beaney. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- Machado, T. (2007). "Historic Canterbury". The Beaney Institute and Royal Museum. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- Gandevia, Bryan (1969). Beaney, James George (1828–1891). Australian Dictionary of Biography. 3. Melbourne University Press. pp. 124–126. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Museums Libraries Archives council: Cornucopia". Royal Museum And Art Gallery. 2007. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Gallery gets £6.5m lottery grant". BBC News. 25 January 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- Crook, Steve. "Powell-Pressburger.org". Filming Locations for ACT. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Library.kent". Giles exhibition. 1 December 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Kentish Gazette". Inquest records verdict of misadventure into death of Canterbury pavement artist. 30 October 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Theatre buys up adjoining garage". BBC News. 7 March 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- Francis, Paul (23 December 2003). "Kent Online". Bid for lottery cash for library. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- "South East England Development Agency". Seeda Gives £2.95 Million to Develop Two Canterbury Arts Centres. 5 March 2008. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- "The Canterbury Beaney". About the project. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- "Tell it as it is". The Poor old Beaney Institute to become a pink elephant. 22 March 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Casson Mann". Beaney Institute. 2009. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Canterbury City Council Online". Beaney collections live on during closure. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Canterbury City Council Online". Beaney News – The Beaney – work begins inside (8 June 09). 8 June 2009. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "The Canterbury Beaney". Press releases. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Kent County Council". Canterbury library. 2010. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- "Wikireadia: 2008 National year of reading". Lark in the Park 2009, Canterbury, Kent. 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- Speel, Bob. "Myweb: Canterbury". The Royal Museum and Free Library (Beaney Institute). Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/33858/page/5521/data.pdf

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Kent Messenger: Kent Online". £5.98m boost for Beaney plans. 22 December 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Roberts, Jo (7 April 2004). "Kent Messenger: Kent Online". City buys £1m portrait. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Information from Canterbury Museums Department

- Stephens, Professor. Old Northern Runic Monuments.

- Cook, Godfrey G. (1941). "Sculptures in the Beaney Institute, Canterbury". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 61: 39–40. doi:10.2307/625970. JSTOR 625970.

- "Canterbury City Council Online". Unique national museum link for Canterbury. CCC. 4 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Army Museum; Ogilby Trust". Buffs, Royal East Kent Regiment Museum Collection. 2010. Archived from the original on 9 October 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- "Canterbury-cathedral.org" (PDF). Guide to researching the history of World War II in Canterbury. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Culture 24". Buffs Regimental Museum, Canterbury. 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

External links

- Beaney project: links to plans and photos

- Museums Libraries Archives (MLA): Beaney museum collections overview

- Photo of St Augustine's chair in 1899

- Sketch from the life, of Dr J.G. Beaney

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beaney House of Art and Knowledge. |