Gregorian mission

The Gregorian mission[1] or Augustinian mission[2] was a Christian mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 596 to convert Britain's Anglo-Saxons.[3] The mission was headed by Augustine of Canterbury. By the time of the death of the last missionary in 653, the mission had established Christianity in southern Britain. Along with the Irish and Frankish missions it converted other parts of Britain as well and influenced the Hiberno-Scottish missions to Continental Europe.

By the time the Roman Empire recalled its legions from the province of Britannia in 410, parts of the island had already been settled by pagan Germanic tribes who, later in the century, appear to have taken control of Kent and other coastal regions no longer defended by the Roman Empire. In the late 6th century Pope Gregory sent a group of missionaries to Kent to convert Æthelberht, King of Kent, whose wife, Bertha of Kent, was a Frankish princess and practising Christian. Augustine had been the prior of Gregory's own monastery in Rome and Gregory prepared the way for the mission by soliciting aid from the Frankish rulers along Augustine's route. In 597, the forty missionaries arrived in Kent and were permitted by Æthelberht to preach freely in his capital of Canterbury.

Soon the missionaries wrote to Gregory telling him of their success, and of the conversions taking place. The exact date of Æthelberht's conversion is unknown but it occurred before 601. A second group of monks and clergy was dispatched in 601 bearing books and other items for the new foundation. Gregory intended Augustine to be the metropolitan archbishop of the southern part of the British Isles, and gave him power over the clergy of the native Britons, but in a series of meetings with Augustine the long-established Celtic bishops refused to acknowledge his authority.

Before Æthelberht's death in 616, a number of other bishoprics had been established. However, after that date, a pagan backlash set in and the see, or bishopric, of London was abandoned. Æthelberht's daughter, Æthelburg, married Edwin, the king of the Northumbrians, and by 627 Paulinus, the bishop who accompanied her north, had converted Edwin and a number of other Northumbrians. When Edwin died, in about 633, his widow and Paulinus were forced to flee back to Kent. Although the missionaries could not remain in all of the places they had evangelised, by the time the last of them died in 653, they had established Christianity in Kent and the surrounding countryside and contributed a Roman tradition to the practice of Christianity in Britain.

Background

By the 4th century the Roman province of Britannia was converted to Christianity and had even produced its own heretic in Pelagius.[7][8] Britain sent three bishops to the Synod of Arles in 314, and a Gaulish bishop went to the island in 396 to help settle disciplinary matters.[9] Lead baptismal basins and other artefacts bearing Christian symbols testify to a growing Christian presence at least until about 360.[10]

After the Roman legions withdrew from Britannia in 410 the natives of Great Britain were left to defend themselves, and non-Christian Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—generally referred to collectively as Anglo-Saxons—settled the southern parts of the island. Though most of Britain remained Christian, isolation from Rome bred a number of distinct practices—Celtic Christianity[7][8]—including emphasis on monasteries instead of bishoprics, differences in calculation of the date of Easter, and a modified clerical tonsure.[8][11] Evidence for the continued existence of Christianity in eastern Britain at this time includes the survival of the cult of Saint Alban and the occurrence of eccles—from the Latin for church—in place names.[12] There is no evidence that these native Christians tried to convert the Anglo-Saxon newcomers.[13][14]

The Anglo-Saxon invasions coincided with the disappearance of most remnants of Roman civilisation in the areas held by the Anglo-Saxons, including the economic and religious structures.[15] Whether this was a result of the Angles themselves, as the early medieval writer Gildas argued,[16] or mere coincidence is unclear. The archaeological evidence suggests much variation in the way that the tribes established themselves in Britain concurrently with the decline of urban Roman culture in Britain.[17][lower-alpha 2] The net effect was that when Augustine arrived in 597 the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had little continuity with the preceding Roman civilisation. In the words of the historian John Blair, "Augustine of Canterbury began his mission with an almost clean slate."[18]

Sources

Most of the information available on the Gregorian mission comes from the medieval writer Bede, especially his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, or Ecclesiastical History of the English People.[19] For this work Bede solicited help and information from many people including his contemporary abbot at Canterbury as well as a future Archbishop of Canterbury, Nothhelm, who forwarded Bede copies of papal letters and documents from Rome.[20] Other sources are biographies of Pope Gregory, including one written in Northern England around 700 as well as a 9th-century life by a Roman writer. The early Life of Gregory is generally believed to have been based on oral traditions brought to northern England from either Canterbury or Rome, and was completed at Whitby Abbey between 704 and 714.[21][22] This view has been challenged by the historian Alan Thacker, who argues that the Life derives from earlier written works; Thacker suggests that much of the information it contains comes from a work written in Rome shortly after Gregory's death.[23] Gregory's entry in the Liber Pontificalis is short and of little use, but he himself was a writer whose work sheds light on the mission. In addition, over 850 of Gregory's letters survive.[24] A few later writings, such as letters from Boniface, an 8th-century Anglo-Saxon missionary, and royal letters to the papacy from the late 8th century, add additional detail.[25] Some of these letters, however, are only preserved in Bede's work.[21]

Bede represented the native British church as wicked and sinful. In order to explain why Britain was conquered by the Anglo-Saxons, he drew on the polemic of Gildas and developed it further in his own works. Although he found some native British clergy worthy of praise he nevertheless condemned them for their failure to convert the invaders and for their resistance to Roman ecclesiastical authority.[26] This bias may have resulted in his understating British missionary activity. Bede was from the north of England, and this may have led to a bias towards events near his own lands.[27] Bede was writing over a hundred years after the events he was recording with little contemporary information on the actual conversion efforts. Nor did Bede completely divorce his account of the missionaries from his own early 8th-century concerns.[15][lower-alpha 3]

Although a few hagiographies, or saints' biographies, about native British saints survive from the period of the mission, none describes native Christians as active missionaries amongst the Anglo-Saxons. Most of the information about the British church at this time is concerned with the western regions of the island of Great Britain and does not deal with the Gregorian missionaries.[28] Other sources of information include Bede's chronologies, the set of laws issued by Æthelberht in Kent, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was compiled in the late 9th century.[29]

Gregory the Great and his motivations

Immediate background

In 595, when Pope Gregory I decided to send a mission to the Anglo-Saxons,[30] the Kingdom of Kent was ruled by Æthelberht. He had married a Christian princess named Bertha before 588,[31] and perhaps earlier than 560.[21] Bertha was the daughter of Charibert I, one of the Merovingian kings of the Franks. As one of the conditions of her marriage she had brought a bishop named Liudhard with her to Kent as her chaplain.[32] They restored a church in Canterbury that dated to Roman times,[33] possibly the present-day St Martin's Church. Æthelberht was at that time a pagan but he allowed his wife freedom of worship.[32] Liudhard does not appear to have made many converts among the Anglo-Saxons,[34] and if not for the discovery of a gold coin, the Liudhard medalet, bearing the inscription Leudardus Eps (Eps is an abbreviation of Episcopus, the Latin word for bishop) his existence may have been doubted.[35] One of Bertha's biographers states that, influenced by his wife, Æthelberht requested Pope Gregory to send missionaries.[32] The historian Ian Wood feels that the initiative came from the Kentish court as well as the queen.[36]

Motivations

Most historians take the view that Gregory initiated the mission, although exactly why remains unclear. A famous story recorded by Bede, an 8th-century monk who wrote a history of the British Church, relates that Gregory saw fair-haired Anglo-Saxon slaves from Britain in the Roman slave market and was inspired to try to convert their people. Supposedly Gregory inquired about the identity of the slaves, and was told that they were Angles from the island of Great Britain. Gregory replied that they were not Angles, but Angels.[37][38] The earliest version of this story is from an anonymous Life of Gregory written at Whitby Abbey about 705.[39] Bede, as well as the Whitby Life of Gregory, records that Gregory himself had attempted to go on a missionary journey to Britain before becoming pope.[40] In 595 Gregory wrote to one of the papal estate managers in southern Gaul, asking that he buy English slave boys in order that they might be educated in monasteries. Some historians have seen this as a sign that Gregory was already planning the mission to Britain at that time, and that he intended to send the slaves as missionaries, although the letter is also open to other interpretations.[40][41]

The historian N. J. Higham speculates that Gregory had originally intended to send the British slave boys as missionaries, until in 596 he received news that Liudhard had died, thus opening the way for more serious missionary activity. Higham argues that it was the lack of any bishop in Britain which allowed Gregory to send Augustine, with orders to be consecrated as a bishop if needed. Another consideration was that cooperation would be more easily obtained from the Frankish royal courts if they no longer had their own bishop and agent in place.[42]

Higham theorises that Gregory believed that the end of the world was imminent, and that he was destined to be a major part of God's plan for the apocalypse. His belief was rooted in the idea that the world would go through six ages, and that he was living at the end of the sixth age, a notion that may have played a part in Gregory's decision to dispatch the mission. Gregory not only targeted the British with his missionary efforts, but he also supported other missionary endeavours,[43] encouraging bishops and kings to work together for the conversion of non-Christians within their territories.[44] He urged the conversion of the heretical Arians in Italy and elsewhere, as well as the conversion of Jews. Also pagans in Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica were the subject of letters to officials, urging their conversion.[45]

Some scholars suggest that Gregory's main motivation was to increase the number of Christians;[46] others wonder if more political matters such as extending the primacy of the papacy to additional provinces and the recruitment of new Christians looking to Rome for leadership were also involved. Such considerations may have also played a part, as influencing the emerging power of the Kentish Kingdom under Æthelberht could have had some bearing on the choice of location.[33] Also, the mission may have been an outgrowth of the missionary efforts against the Lombards.[47] At the time of the mission Britain was the only part of the former Roman Empire which remained in pagan hands and the historian Eric John argues that Gregory desired to bring the last remaining pagan area of the old empire back under Christian control.[48]

Practical considerations

The choice of Kent and Æthelberht was almost certainly dictated by a number of factors, including that Æthelberht had allowed his Christian wife to worship freely. Trade between the Franks and Æthelberht's kingdom was well established, and the language barrier between the two regions was apparently only a minor obstacle as the interpreters for the mission came from the Franks. Another reason for the mission was the growing power of the Kentish kingdom. Since the eclipse of King Ceawlin of Wessex in 592, Æthelberht was the leading Anglo-Saxon ruler; Bede refers to Æthelberht as having imperium, or overlordship, south of the River Humber. Lastly, the proximity of Kent to the Franks allowed for support from a Christian area.[49] There is some evidence, including Gregory's letters to Frankish kings in support of the mission, that some of the Franks felt they had a claim to overlordship over some of the southern British kingdoms at this time. The presence of a Frankish bishop could also have lent credence to claims of overlordship, if Liudhard was felt to be acting as a representative of the Frankish Church and not merely as a spiritual adviser to the queen. Archaeological remains support the notion that there were cultural influences from Francia in England at that time.[50]

Preparations

In 595, Gregory chose Augustine, prior of Gregory's own monastery of St Andrew in Rome, to head the mission to Kent.[46] Gregory selected monks to accompany Augustine and sought support from the Frankish kings. The pope wrote to a number of Frankish bishops on Augustine's behalf, introducing the mission and asking that Augustine and his companions be made welcome. Copies of letters to some of these bishops survive in Rome. The pope wrote to King Theuderic II of Burgundy and to King Theudebert II of Austrasia, as well as their grandmother Brunhilda of Austrasia, seeking aid for the mission. Gregory thanked King Chlothar II of Neustria for aiding Augustine. Besides hospitality, the Frankish bishops and kings provided interpreters and were asked to allow some Frankish priests to accompany the mission.[51] By soliciting help from the Frankish kings and bishops, Gregory helped to ensure a friendly reception for Augustine in Kent, as Æthelbert was unlikely to mistreat a mission which enjoyed the evident support of his wife's relatives and people.[52] The Franks at that time were attempting to extend their influence in Kent, and assisting Augustine's mission furthered that goal. Chlothar, in particular, needed a friendly realm across the Channel to help guard his kingdom's flanks against his fellow Frankish kings.[53]

Arrival and first efforts

Composition and arrival

The mission consisted of about forty missionaries, some of whom were monks.[31] Soon after leaving Rome, the missionaries halted, daunted by the nature of the task before them. They sent Augustine back to Rome to request papal permission to return, which Gregory refused, and instead sending Augustine back with letters to encourage the missionaries to persevere.[54] Another reason for the pause may have been the receipt of news of the death of King Childebert II, who had been expected to help the missionaries; Augustine may have returned to Rome to secure new instructions and letters of introduction, as well as to update Gregory on the new political situation in Gaul. Most likely, they halted in the Rhone valley.[42] Gregory also took the opportunity to name Augustine as abbot of the mission. Augustine then returned to the rest of the missionaries, with new instructions, probably including orders to seek consecration as a bishop on the Continent if the conditions in Kent warranted it.[55]

In 597 the mission landed in Kent,[31] and it quickly achieved some initial success:[47][56] Æthelberht permitted the missionaries to settle and preach in his capital of Canterbury, where they used the church of St. Martin's for services,[57] and this church became the seat of the bishopric.[47] Neither Bede nor Gregory mentions the date of Æthelberht's conversion,[58] but it probably took place in 597.[57][lower-alpha 4]

Process of conversion

In the early medieval period, large-scale conversions required the ruler's conversion first, and large numbers of converts are recorded within a year of the mission's arrival in Kent.[57] By 601, Gregory was writing to both Æthelberht and Bertha, calling the king his son and referring to his baptism.[lower-alpha 5] A late medieval tradition, recorded by the 15th-century chronicler Thomas Elmham, gives the date of the king's conversion as Whit Sunday, or 2 June 597; there is no reason to doubt this date, but there is no other evidence for it.[57] A letter of Gregory's to Patriarch Eulogius of Alexandria in June 598 mentions the number of converts made, but does not mention any baptism of the king in 597, although it is clear that by 601 he had been converted.[59][lower-alpha 6] The royal baptism probably took place at Canterbury but Bede does not mention the location.[61]

Why Æthelberht chose to convert to Christianity is uncertain. Bede suggests that the king converted strictly for religious reasons, but most modern historians see other motives behind Æthelberht's decision.[62] Certainly, given Kent's close contacts with Gaul, it is possible that Æthelberht sought baptism in order to smooth his relations with the Merovingian kingdoms, or to align himself with one of the factions then contending in Gaul.[63] Another consideration may have been that new methods of administration often followed conversion, whether directly from the newly introduced church or indirectly from other Christian kingdoms.[64]

Evidence from Bede suggests that, although Æthelberht encouraged conversion, he could not compel his subjects to become Christians. The historian R. A. Markus feels that this was due to a strong pagan presence in the kingdom that forced the king to rely on indirect means including royal patronage and friendship to secure conversions.[65] For Markus this is demonstrated by the way in which Bede describes the king's conversion efforts which, when a subject converted, were to "rejoice at their conversion" and to "hold believers in greater affection".[66]

Instructions and missionaries from Rome

After these conversions, Augustine sent Laurence back to Rome with a report of his success along with questions about the mission.[67] Bede records the letter and Gregory's replies in chapter 27 of his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, this section of the History is usually known as the Libellus responsionum.[68][69] Augustine asked for Gregory's advice on some issues, including how to organise the church, the punishment for church robbers, guidance on who was allowed to marry whom, and the consecration of bishops. Other topics were relations between the churches of Britain and Gaul, childbirth and baptism, and when it was lawful for people to receive communion and for a priest to celebrate mass.[69][lower-alpha 7] Other than the trip by Laurence, little is known of the activities of the missionaries in the period from their arrival until 601. Gregory mentions the mass conversions, and there is mention of Augustine working miracles that helped win converts, but there is little evidence of specific events.[72]

According to Bede, further missionaries were sent from Rome in 601. They brought a pallium for Augustine, gifts of sacred vessels, vestments, relics, and books. The pallium was the symbol of metropolitan status, and signified that Augustine was in union with the Roman papacy. Along with the pallium, a letter from Gregory directed the new archbishop to ordain twelve suffragan bishops as soon as possible, and to send a bishop to York. Gregory's plan was that there would be two metropolitan sees, one at York and one at London, with twelve suffragan bishops under each archbishop. Augustine was also instructed to transfer his archiepiscopal see to London from Canterbury, which never happened,[73] perhaps because London was not part of Æthelberht's domain.[33] Also, London remained a stronghold of paganism, as events after the death of Æthelberht revealed.[74] London at that time was part of the Kingdom of Essex, which was ruled by Æthelberht's nephew Sæbert of Essex, who converted to Christianity in 604.[33][75] The historian S. Brechter has suggested that the metropolitan see was indeed moved to London, and that it was only with the abandonment of London as a see after Æthelberht's death that Canterbury became the archiepiscopal see, contradicting Bede's version of events.[25] The choice of London as Gregory's proposed southern archbishopric was probably due to his understanding of how Britain was administered under the Romans, when London was the principal city of the province.[74]

Along with the letter to Augustine, the returning missionaries brought a letter to Æthelberht that urged the king to act like the Roman Emperor Constantine I and force the conversion of his followers to Christianity. The king was also urged to destroy all pagan shrines. However, Gregory also wrote a letter to Mellitus,[76] the Epistola ad Mellitum of July 601,[77] in which the pope took a different tack in regards to pagan shrines, suggesting that they be cleansed of idols and converted to Christian use rather than destroyed;[76] the pope compared the Anglo-Saxons to the ancient Israelites, a recurring theme in Gregory's writings.[77] He also suggested that the Anglo-Saxons build small huts much like those built during the Jewish festival of Sukkot, to be used during the annual autumn slaughter festivals so as to gradually change the Anglo-Saxon pagan festivals into Christian ones.[78]

The historian R. A. Markus suggests that the reason for the conflicting advice is that the letter to Æthelberht was written first, and sent off with the returning missionaries. Markus argues that the pope, after thinking further about the circumstances of the mission in Britain, then sent a follow-up letter, the Epistolae ad Mellitum, to Mellitus, then en route to Canterbury, which contained new instructions. Markus sees this as a turning point in missionary history, in that forcible conversion gave way to persuasion.[76] This traditional view that the Epistola represents a contradiction of the letter to Æthelberht has been challenged by George Demacopoulos who argues that the letter to Æthelberht was mainly meant to encourage the king in spiritual matters, while the Epistola was sent to deal with purely practical matters, and thus the two do not contradict each other.[79] Flora Spiegel, a writer on Anglo-Saxon literature, suggests that the theme of comparing the Anglo-Saxons to the Israelites was part of a conversion strategy involving gradual steps, including an explicitly proto-Jewish one between paganism and Christianity. Spiegel sees this as an extension of Gregory's view of Judaism as halfway between Christianity and paganism. Thus, Gregory felt that first the Anglo-Saxons must be brought up to the equivalent of Jewish practices, then after that stage was reached they could be brought completely up to Christian practices.[78]

Church building

Bede relates that after the mission's arrival in Kent and conversion of the king, they were allowed to restore and rebuild old Roman churches for their use. One such was Christ Church, Canterbury, which became Augustine's cathedral church. Archaeological evidence for other Roman churches having been rebuilt is slight, but the church of St Pancras in Canterbury has a Roman building at its core, although it is unclear whether that older building was a church during the Roman era. Another possible site is Lullingstone, in Kent, where a religious site dating to 300 was found underneath an abandoned church.[80]

Soon after his arrival, Augustine founded the monastery of Saints Peter and Paul,[47] to the east of the city, just outside the walls, on land donated by the king.[81] After Augustine's death, it was renamed St Augustine's Abbey. This foundation has often been claimed as the first Benedictine abbey outside Italy, and that by founding it Augustine introduced the Rule of St. Benedict into England, but there is no evidence that the abbey followed the Benedictine Rule at the time of its foundation.[82]

Efforts in the south

Relations with the British Christians

Gregory had ordered that the native British bishops were to be governed by Augustine and, consequently, Augustine arranged a meeting with some of the native clergy some time between 602 and 604.[83] The meeting took place at a tree later given the name "Augustine's Oak",[84] probably around the present-day boundary between Somerset and Gloucestershire.[85][lower-alpha 8] Augustine apparently argued that the British church should give up any of its customs not in accordance with Roman practices, including the dating of Easter. He also urged them to help with the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons.[84]

After some discussion, the local bishops stated that they needed to consult with their own people before agreeing to Augustine's requests, and left the meeting. Bede relates that a group of native bishops consulted an old hermit who said they should obey Augustine if, when they next met with him, Augustine rose when he greeted the natives. But if Augustine failed to stand up when they arrived for the second meeting, they should not submit. When Augustine failed to rise to greet the second delegation of British bishops at the next meeting, Bede says the native bishops refused to submit to Augustine.[83] Bede then has Augustine proclaim a prophecy that because of lack of missionary effort towards the Anglo-Saxons from the British church, the native church would suffer at the hands of the Anglo-Saxons. This prophecy was seen as fulfilled when Æthelfrith of Northumbria supposedly killed 1200 native monks at the Battle of Chester.[84] Bede uses the story of Augustine's two meetings with two groups of British bishops as an example of how the native clergy refused to cooperate with the Gregorian mission.[83] Later, Aldhelm, the abbot of Malmesbury, writing in the later part of the 7th century, claimed that the native clerks would not eat with the missionaries, nor would they perform Christian ceremonies with them.[84] Laurence, Augustine's successor, writing to the Irish bishops during his tenure of Canterbury, also stated that an Irish bishop, Dagan, would not share meals with the missionaries.[87]

One probable reason for the British clergy's refusal to cooperate with the Gregorian missionaries was the ongoing conflict between the natives and the Anglo-Saxons, who still were encroaching upon British lands at the time of the mission. The British were unwilling to preach to the invaders of their country, and the invaders saw the natives as second-class citizens, and would have been unwilling to listen to any conversion efforts. There was also a political dimension, as the missionaries could be seen as agents of the invaders;[84] because Augustine was protected by Æthelberht, submitting to Augustine would have been seen as submitting to Æthelberht's authority, which the British bishops would have been unwilling to do.[88]

Most of the information on the Gregorian mission comes from Bede's narrative, and this reliance on one source necessarily leaves the picture of native missionary efforts skewed. First, Bede's information is mainly from the north and the east of Britain. The western areas, where the native clergy was strongest, was an area little covered by Bede's informants. In addition, although Bede presents the native church as one entity, in reality the native British were divided into a number of small political units, which makes Bede's generalisations suspect.[84] The historian Ian Wood argues that the existence of the Libellus points to more contact between Augustine and the native Christians because the topics covered in the work are not restricted to conversion from paganism, but also dealt with relations between differing styles of Christianity. Besides the text of the Libellus contained within Bede's work, other versions of the letter circulated, some of which included a question omitted from Bede's version. Wood argues that the question, which dealt with the cult of a native Christian saint, is only understandable if this cult impacted Augustine's mission, which would imply that Augustine had more relations with the local Christians than those related by Bede.[89]

Spread of bishoprics and church affairs

In 604, another bishopric was founded, this time at Rochester, where Justus was consecrated as bishop. The king of Essex was converted in the same year, allowing another see to be established at London, with Mellitus as bishop.[90] Rædwald, the king of the East Angles, also was converted, but no see was established in his territory.[91] Rædwald had been converted while visiting Æthelberht in Kent, but when he returned to his own court he worshiped pagan gods as well as the Christian god.[92] Bede relates that Rædwald's backsliding was because of his still-pagan wife, but the historian S. D. Church sees political implications of overlordship behind the vacillation about conversion.[93] When Augustine died in 604, Laurence, another missionary, succeeded him as archbishop.[94]

The historian N. J. Higham suggests that a synod, or ecclesiastical conference to discuss church affairs and rules, was held at London during the early years of the mission, possibly shortly after 603. Boniface, an Anglo-Saxon native who became a missionary to the continental Saxons, mentions such a synod being held at London. Boniface says that the synod legislated on marriage, which he discussed with Pope Gregory III in 742. Higham argues that because Augustine had asked for clarifications on the subject of marriage from Gregory the Great, it is likely that he could have held a synod to deliberate on the issue.[95] Nicholas Brooks, another historian, is not so sure that there was such a synod, but does not completely rule out the possibility. He suggests it might have been that Boniface was influenced by a recent reading of Bede's work.[96]

The rise of Æthelfrith of Northumbria in the north of Britain limited Æthelbertht's ability to expand his kingdom as well as limiting the spread of Christianity. Æthelfrith took over Deira about 604, adding it to his own realm of Bernicia.[97] However, the Frankish kings in Gaul were increasingly involved in internal power struggles, leaving Æthelbertht free to continue to promote Christianity within his own lands. The Kentish Church sent Justus, then Bishop of Rochester, and Peter, the abbot of Sts Peter and Paul Abbey in Canterbury, to the Council of Paris in 614, probably with Æthelbertht's support. Æthelbertht also promulgated a code of laws, which was probably influenced by the missionaries.[98]

Pagan reactions

A pagan reaction set in following Æthelbert's death in 616; Mellitus was expelled from London never to return,[91] and Justus was expelled from Rochester, although he eventually managed to return after spending some time with Mellitus in Gaul. Bede relates a story that Laurence was preparing to join Mellitus and Justus in Francia when he had a dream in which Saint Peter appeared and whipped Laurence as a rebuke for his plans to leave his mission. When Laurence woke whip marks had miraculously appeared on his body. He showed these to the new Kentish king, who promptly was converted and recalled the exiled bishops.[99]

The historian N. J. Higham sees political factors at work in the expulsion of Mellitus, as it was Sæberht's sons who banished Mellitus. Bede said that the sons had never been converted, and after Æthelberht's death they attempted to force Mellitus to give them the Eucharist without ever becoming Christians, seeing the Eucharist as magical. Although Bede does not give details of any political factors surrounding the event, it is likely that by expelling Mellitus the sons were demonstrating their independence from Kent, and repudiating the overlordship that Æthelberht had exercised over the East Saxons. There is no evidence that Christians among the East Saxons were mistreated or oppressed after Mellitus' departure.[100]

Æthelberht was succeeded in Kent by his son Eadbald. Bede states that after Æthelberht's death Eadbald refused to be baptised and married his stepmother, an act forbidden by the teachings of the Roman Church. Although Bede's account makes Laurence's miraculous flogging the trigger for Eadbald's baptism, this completely ignores the political and diplomatic problems facing Eadbald. There are also chronological problems with Bede's narrative, as surviving papal letters contradict Bede's account.[101] Historians differ on the exact date of Eadbald's conversion. D. P. Kirby argues that papal letters imply that Eadbald was converted during the time that Justus was Archbishop of Canterbury, which was after Laurence's death, and long after the death of Æthelberht.[102] Henry Mayr-Harting accepts the Bedan chronology as correct, and feels that Eadbald was baptised soon after his father's death.[94] Higham agrees with Kirby that Eadbald did not convert immediately, contending that the king supported Christianity but did not convert for at least eight years after his father's death.[103]

Spread of Christianity to Northumbria

The spread of Christianity in the north of Britain gained ground when Edwin of Northumbria married Æthelburg, a daughter of Æthelbert, and agreed to allow her to continue to worship as a Christian. He also agreed to allow Paulinus of York to accompany her as a bishop, and for Paulinus to preach to the court. By 627, Paulinus had converted Edwin, and on Easter, 627, Edwin was baptised. Many others were baptised after the king's conversion.[91] The exact date when Paulinus went north is unclear;[104] some historians argue for 625, the traditional date,[91] whereas others believe that it was closer to 619.[104] Higham argues that the marriage alliance was part of an attempt by Eadbald, brother of the bride, to capitalise on the death of Rædwald in about 624, in an attempt to regain the overkingship his father had once enjoyed. According to Higham, Rædwald's death also removed one of the political factors keeping Eadbald from converting, and Higham dates Eadbald's baptism to the time that his sister was sent to Northumbria. Although Bede's account gives all the initiative to Edwin, it is likely that Eadbald also was active in seeking such an alliance.[105] Edwin's position in the north also was helped by Rædwald's death, and Edwin seems to have held some authority over other kingdoms until his death.[106]

Paulinus was active not only in Deira, which was Edwin's powerbase, but also in Bernicia and Lindsey. Edwin planned to set up a northern archbishopric at York, following Gregory the Great's plan for two archdioceses in Britain. Both Edwin and Eadbald sent to Rome to request a pallium for Paulinus, which was sent in July 634. Many of the East Angles, whose king, Eorpwald appears to have converted to Christianity, were also converted by the missionaries.[107] Following Edwin's death in battle, in either 633[91] or 634,[107] Paulinus returned to Kent with Edwin's widow and daughter. Only one member of Paulinus' group stayed behind, James the Deacon.[91] After Justus' departure from Northumbria, a new king, Oswald, invited missionaries from the Irish monastery of Iona, who worked to convert the kingdom.[108]

About the time that Edwin died in 633, a member of the East Anglian royal family, Sigeberht, returned to Britain after his conversion while in exile in Francia. He asked Honorius, one of the Gregorian missionaries who was then Archbishop of Canterbury, to send him a bishop, and Honorius sent Felix of Burgundy, who was already a consecrated bishop; Felix succeeded in converting the East Angles.[109]

Other aspects

The Gregorian missionaries focused their efforts in areas where Roman settlement had been concentrated. It is possible that Gregory, when he sent the missionaries, was attempting to restore a form of Roman civilisation to England, modelling the church's organisation after that of the church in Francia at that time. Another aspect of the mission was how little of it was based on monasticism. One monastery was established at Canterbury, which later became St Augustine's Abbey, but although Augustine and some of his missionaries had been monks, they do not appear to have lived as monks at Canterbury. Instead, they lived more as secular clergy serving a cathedral church, and it appears likely that the sees established at Rochester and London were organised along similar lines.[110] The Gaulish and Italian churches were organised around cities and the territories controlled by those cities. Pastoral services were centralised, and churches were built in the larger villages of the cities' territorial rule. The seat of the bishopric was established in the city and all churches belonged to the diocese, staffed by the bishop's clergy.[111]

Most modern historians have noted how the Gregorian missionaries come across in Bede's account as colourless and boring, compared to the Irish missionaries in Northumbria, and this is related directly to the way Bede gathered his information. The historian Henry Mayr-Harting argues that in addition, most of the Gregorian missionaries were concerned with the Roman virtue of gravitas, or personal dignity not given to emotional displays, and this would have limited the colourful stories available about them.[112]

One reason for the mission's success was that it worked by example. Also important was Gregory's flexibility and willingness to allow the missionaries to adjust their liturgies and behaviour.[34] Another reason was the willingness of Æthelberht to be baptised by a non-Frank. The king would have been wary of allowing the Frankish bishop Liudhard to convert him, as that might open Kent up to Frankish claims of overlordship. But being converted by an agent of the distant Roman pontiff was not only safer, it allowed the added prestige of accepting baptism from the central source of the Latin Church. As the Roman Church was considered part of the Roman Empire in Constantinople, this also would gain Æthelberht acknowledgement from the emperor.[113] Other historians have attributed the success of the mission to the substantial resources Gregory invested in its success; he sent over forty missionaries in the first group, with more joining them later, a quite significant number.[48]

Legacy

The last of Gregory's missionaries, Archbishop Honorius, died on 30 September 653. He was succeeded as archbishop by Deusdedit, a native Englishman.[114]

Pagan practices

The missionaries were forced to proceed slowly, and could not do much about eliminating pagan practices, or destroying temples or other sacred sites, unlike the missionary efforts that had taken place in Gaul under St Martin.[115] There was little fighting or bloodshed during the mission.[116] Paganism was still practised in Kent until the 630s, and it was not declared illegal until 640.[117] Although Honorius sent Felix to the East Angles, it appears that most of the impetus for conversion came from the East Anglian king.[118]

With the Gregorian missionaries, a third strand of Christian practice was added to the British Isles, to combine with the Gaulish and the Hiberno-British strands already present. Although it is often suggested that the Gregorian missionaries introduced the Rule of Saint Benedict into England, there is no supporting evidence.[119] The early archbishops at Canterbury claimed supremacy over all the bishops in the British Isles, but their claim was not acknowledged by most of the rest of the bishops. The Gregorian missionaries appear to have played no part in the conversion of the West Saxons, who were converted by Birinus, a missionary sent directly by Pope Honorius I. Neither did they have much lasting influence in Northumbria, where after Edwin's death the conversion of the Northumbrians was achieved by missionaries from Iona, not Canterbury.[118]

Papal aspects

An important by-product of the Gregorian mission was the close relationship it fostered between the Anglo-Saxon Church and the Roman Church.[120] Although Gregory had intended for the southern archiepiscopal see to be located at London, that never happened. A later tradition, dating from 797, when an attempt was made to move the archbishopric from Canterbury to London by King Coenwulf of Mercia, stated that on the death of Augustine, the "wise men" of the Anglo-Saxons met and decided that the see should remain at Canterbury, for that was where Augustine had preached.[121] The idea that an archbishop needed a pallium in order to exercise his archiepiscopal authority derives from the Gregorian mission, which established the custom at Canterbury from where it was spread to the Continent by later Anglo-Saxon missionaries such as Willibrord and Boniface.[114] The close ties between the Anglo-Saxon church and Rome were strengthened later in the 7th century when Theodore of Tarsus was appointed to Canterbury by the papacy.[122]

The mission was part of a movement by Gregory to turn away from the East, and look to the Western parts of the old Roman Empire. After Gregory, a number of his successors as pope continued in the same vein, and maintained papal support for the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons.[123] The missionary efforts of Augustine and his companions, along with those of the Hiberno-Scottish missionaries, were the model for the later Anglo-Saxon missionaries to Germany.[124] The historian R. A. Markus suggests that the Gregorian mission was a turning point in papal missionary strategy, marking the beginnings of a policy of persuasion rather than coercion.[76]

Cults of the saints

Another effect of the mission was the promotion of the cult of Pope Gregory the Great by the Northumbrians amongst others; the first Life of Gregory is from Whitby Abbey in Northumbria.[lower-alpha 9] Gregory was not popular in Rome, and it was not until Bede's Ecclesiastical History began to circulate that Gregory's cult also took root there.[123] Gregory, in Bede's work, is the driving force behind the Gregorian mission, and Augustine and the other missionaries are portrayed as depending on him for advice and help in their endeavours.[126] Bede also gives a leading role in the conversion of Northumbria to Gregorian missionaries, especially in his Chronica Maiora, in which no mention is made of any Irish missionaries.[127] By putting Gregory at the centre of the mission, even though he did not take part in it, Bede helped to spread the cult of Gregory, who not only became one of the major saints in Anglo-Saxon England, but continued to overshadow Augustine even in the afterlife; an Anglo-Saxon church council of 747 ordered that Augustine should always be mentioned in the liturgy right after Gregory.[128]

A number of the missionaries were considered saints, including Augustine, who became another cult figure;[129] the monastery he founded in Canterbury was eventually rededicated to him.[47] Honorius,[130] Justus,[131] Lawrence,[132] Mellitus,[133] Paulinus,[134] and Peter, were also considered saints,[135] along with Æthelberht, of whom Bede said that he continued to protect his people even after death.[61]

Art, architecture, and music

A few objects at Canterbury have traditionally been linked with the mission, including the 6th-century St Augustine Gospels produced in Italy, now held at Cambridge as Corpus Christi College MS 286.[136][137][138] There is a record of an illuminated and imported Bible of St Gregory, now lost, at Canterbury in the 7th century.[139] Thomas of Elmham, in the late 15th century, described a number of other books held at that time by St Augustine's Abbey, believed to have been gifts to the abbey from Augustine. In particular, Thomas recorded a psalter as being associated with Augustine, which the antiquary John Leland saw at the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s, but it has since disappeared.[140][lower-alpha 10]

Augustine built a church at his foundation of Sts Peter and Paul Abbey at Canterbury, later renamed St Augustine's Abbey. This church was destroyed after the Norman Conquest to make way for a new abbey church.[143] The mission also established Augustine's cathedral at Canterbury, which became Christ Church Priory.[144] This church has not survived, and it is unclear if the church that was destroyed in 1067 and described by the medieval writer Eadmer as Augustine's church, was built by Augustine. Another medieval chronicler, Florence of Worcester, claimed that the priory was destroyed in 1011, and Eadmer himself had contradictory stories about the events of 1011, in one place claiming that the church was destroyed by fire and in another claiming only that it was looted.[145] A cathedral was also established in Rochester; although the building was destroyed in 676, the bishopric continued in existence.[146][147] Other church buildings were erected by the missionaries in London, York, and possibly Lincoln,[148] although none of them survive.[149]

The missionaries introduced a musical form of chant into Britain, similar to that used in Rome during the mass.[150] During the 7th and 8th centuries Canterbury was renowned for the excellence of its clergy's chanting, and sent singing masters to instruct others, including two to Wilfrid, who became Bishop of York. Putta, the first Bishop of Hereford, had a reputation for his skill at chanting, which he was said to have learned from the Gregorian missionaries.[151] One of them, James the Deacon, taught chanting in Northumbria after Paulinus returned to Kent; Bede noted that James was accomplished in the singing of the chants.[152]

Legal codes and documents

The historian Ann Williams has argued that the missionaries' familiarity with the Roman law, recently codified by the Emperor Justinian in the Corpus Iuris Civilis promulgated in 534, were an influence on the English kings promulgating their own law codes.[153] Bede specifically calls Æthelberht's code a "code of law after the Roman manner".[154] Another influence, also introduced by the missionaries, on the early English law codes was the Old Testament legal codes. Williams sees the issuing of legal codes as not just laws but also as statements of royal authority, showing that the kings were not just warlords but also lawgivers and capable of securing peace and justice in their kingdoms.[153] It has also been suggested that the missionaries contributed to the development of the charter in England, for the earliest surviving charters show not just Celtic and Frankish influences but also Roman touches. Williams argues that it is possible that Augustine introduced the charter into Kent.[155]

See also

- List of members of the Gregorian mission – Italian monks and priests sent by Pope Gregory the Great to Britain in the 7th century

Notes

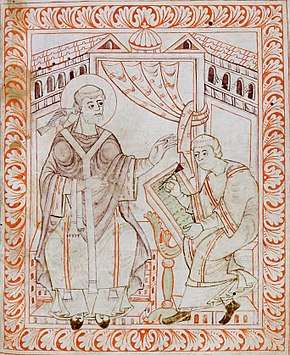

- The name is in the halo, in a later hand. The figure is identified as a saint by his clerical tonsure, and is the earliest surviving historiated initial.[4] The view that it represents Gregory is set out by Douglas Dales in a recent article.[5][6]

- This evidence consists mainly of the number and the density of pagan burials. Burials also show variation in grave-goods, some regions having more weapons and armor in the burials than others, suggesting those regions were settled with more warriors. Often the burials lacking weapons also show signs of malnutrition in the bones, indicating those burials were of peasants. Some of the regions settled by the pagan tribes show a greater number of peasant burials than others, implying that the settlement there was more peaceful.[17]

- Bede's purposes and biases are discussed in a number of recent works, including N. J. Higham's (Re)-reading Bede: The Ecclesiastical History in Context (ISBN 0-415-35368-8) and Walter Goffart's The Narrators of Barbarian History: Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon (ISBN 0-691-05514-9)

- Bede's chronology may be a little awry, as he gives the king's death as occurring in February 616, and says the king died 21 years after his conversion, which would date the conversion to 595. This would be before the mission and would mean that either the queen or Liudhard converted Æthelberht, which contradicts Bede's own statement that the king's conversion was due to the Gregorian mission.[21] Since Gregory in his letter of 601 to the king and queen strongly implies that the queen could not effect the conversion of her husband, thus providing independent testimony to Æthelberht's conversion by the mission, the problem of the dating is likely a chronological error on Bede's part.[59]

- The letter, as translated in Brooks' Early History of the Church of Canterbury, p. 8, says "preserve the grace he had received". Grace in this context meant the grace of baptism.

- Attempts by Suso Brechter to argue that Æthelberht was not converted until after 601 have met with little agreement among medievalists.[59][60]

- Historians have debated whether the Libellus is a genuine document from Gregory.[70] The historian Rob Meens argues the concerns with ritual purity that pervade the Libellus stemmed from Augustine having encountered local Christians who had customs resembling the Old Testament's rules on purity.[71]

- Sometimes it is recorded as the Synod of Chester.[86]

- By contrast, although the Whitby Life dates to the late-7th or early-8th century, the first Roman Life of Gregory did not appear until the 9th century.[125]

- Another possible survivor is a copy of the Rule of St Benedict, now MS Oxford Bodleian Hatton 48.[141] Another Gospel, in an Italian hand, and closely related to the Augustine Gospels, is MS Oxford Bodelian Auctarium D.2.14, which shows evidence of being held in Anglo-Saxon hands during the right time frame, and thus may have been brought to England by the mission. Lastly, a fragment of a work by Gregory the Great, now held by the British Library as part of MS Cotton Titus C may have arrived with the missionaries.[142]

Citations

- Jones "Gregorian Mission" Speculum p. 335

- McGowan "Introduction to the Corpus" Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature p. 17

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 50

- Schapiro "Decoration of the Leningrad Manuscript of Bede" Selected Papers: Volume 3 pp. 199; 212–214

- Dales "Apostle of the English" L'eredità spirituale di Gregorio Magno tra Occidente e Oriente p. 299

- Wilson Anglo-Saxon Art p. 63

- Hindley Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons pp. 3–9

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity pp. 78–93

- Frend "Roman Britain" Cross Goes North pp. 80–81

- Frend "Roman Britain" Cross Goes North pp. 82–86

- Yorke Conversion of Britain pp. 115–118 discusses the issue of the "Celtic Church" and what exactly it was.

- Yorke Conversion of Britain p. 121

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 102

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 32

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 23

- Yorke Kings and Kingdoms pp. 1–2

- Yorke Kings and Kingdoms pp. 5–7

- Blair Church in Anglo-Saxon Society pp. 24–25

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 40

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 69

- Kirby Earliest English Kings pp. 24–25

- Thacker "Memorializing" Early Medieval Europe p. 63

- Thacker "Memorializing" Early Medieval Europe pp. 59–71

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 52

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 11–14

- Foley and Higham "Bede on the Britons" Early Medieval Europe pp. 154–156

- Yorke Conversion p. 21

- Kirby Making of Early England p. 39

- Yorke Conversion pp. 6–7

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England pp. 104–105

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England pp. 105–106

- Nelson "Bertha" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Hindley Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons pp. 33–36

- Herrin Formation of Christendom p. 169

- Higham Convert Kings p. 73

- Wood "Mission of Augustine of Canterbury" Speculum pp. 9–10

- Bede History of the English Church and People pp. 99–100

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity pp. 57–59

- Fletcher Barbarian Conversion p. 112

- Markus "Chronology of the Gregorian Mission" Journal of Ecclesiastical History pp. 29–30

- Fletcher Barbarian Conversion pp. 113–114

- Higham Convert Kings pp. 74–75

- Higham Convert Kings p. 63

- Markus Gregory the Great and His World p. 82

- Markus "Gregory the Great and a Papal Missionary Strategy" Studies in Church History 6 pp. 30–31

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 104

- Mayr-Harting "Augustine" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- John Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England pp. 28–30

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 6–7

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 27

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 4–5

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury p. 6

- Wood "Mission of Augustine of Canterbury" Speculum p. 9

- Blair Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England pp. 116–117

- Higham Convert Kings pp. 76–77

- Fletcher Barbarian Conversion pp. 116–117

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 8–9

- Wood "Mission of Augustine of Canterbury" Speculum p. 11

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 28

- Markus "Chronology of the Gregorian Mission" Journal of Ecclesiastical History p. 16

- Higham Convert Kings p. 56

- Higham Convert Kings p. 53

- Higham Convert Kings pp. 90–102

- Campbell "Observations" Essays in Anglo-Saxon History p. 76

- Markus Gregory the Great and His World pp. 182–183

- Quoted in Markus Gregory the Great and His World p. 183

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 106

- Lapidge "Laurentius" Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England

- Bede History of the English Church pp. 71–83

- Deanesley and Grosjean "Canterbury Edition" Journal of Ecclesiastical History pp. 1–49

- Meens "Background" Anglo-Saxon England 23 pp. 15–17

- Higham Convert Kings p. 91

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 9–11

- Markus Gregory the Great and His World p. 180

- Fletcher Barbarian Conversion p. 453

- Markus "Gregory the Great and a Papal Missionary Strategy" Studies in Church History 6 pp. 34–37

- Spiegel "'Tabernacula' of Gregory the Great" Anglo-Saxon England 36 pp. 2–3

- Spiegel "'Tabernacula' of Gregory the Great" Anglo-Saxon England 36 pp. 3–6

- Demacopoulos "Gregory the Great and the Pagan Shrines of Kent" Journal of Late Antiquity pp. 353–369

- Church "Paganism in Conversion-age Anglo-Saxon England" History p. 179

- Blair Church in Anglo-Saxon Society pp. 61–62

- Lawrence Medieval Monasticism p. 55

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity pp. 71–72

- Yorke Conversion pp. 118–119

- Blair Church in Anglo-Saxon Society p. 29

- Thacker "Chester" Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 112

- Higham Convert Kings p. 110

- Wood "Augustine and Aidan" L'Église et la Mission p. 170

- Blair Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England p. 117

- Blair Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England pp. 118–119

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 65

- Church "Paganism in Conversion-Age Anglo-Saxon England" History pp. 176–178

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 75

- Higham Convert Kings pp. 112–113

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 13–14

- Higham Convert Kings p. 114

- Higham Convert Kings pp. 115–117

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity pp. 75–76

- Higham Convert Kings pp. 134–136

- Kirby Earliest English Kings pp. 30–33

- Kirby Earliest English Kings pp. 33–34

- Higham Convert Kings pp. 137–138

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity pp. 66–68

- Higham Convert Kings pp. 141–142

- Yorke Kings and Kingdoms p. 78

- Kirby Earliest English Kings pp. 65–66

- Blair Church in Anglo-Saxon Society p. 9

- Blair Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England p. 120

- Blair Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England pp. 132–133

- Blair Church in Anglo-Saxon Society pp. 34–39

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity pp. 69–71

- Brown Rise of Western Christendom pp. 344–345

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 66–67

- Brown Rise of Western Christendom pp. 345–346

- Chaney "Paganism to Christianity" Early Medieval Society p. 67

- Chaney "Paganism to Christianity" Early Medieval Society p. 68

- Brooks Early History of the Church at Canterbury pp. 64–66

- Lawrence Medieval Monasticism pp. 54–55

- Collins Early Medieval Europe p. 185

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury p. 14

- Coates "Episcopal Sanctity" Historical Research p. 7

- Ortenberg "Anglo-Saxon Church" English Church pp. 33–34

- Ortenberg "Anglo-Saxon Church" English Church p. 57

- Thacker "Memorializing Gregory the Great" Early Medieval Europe pp. 59–60

- Gameson and Gameson "From Augustine to Parker" Anglo-Saxons pp. 13–16

- Thacker "Memorializing Gregory the Great" Early Medieval Europe p. 80

- Gameson and Gameson "From Augustine to Parker" Anglo-Saxons p. 15 and footnote 6

- Walsh Dictionary of Saints p. 73

- Walsh Dictionary of Saints p. 268

- Walsh Dictionary of Saints p. 348

- Walsh Dictionary of Saints p. 357

- Walsh Dictionary of Saints p. 420

- Walsh Dictionary of Saints p. 475

- Walsh Dictionary of Saints p. 482

- Dodwell Pictorial Arts pp. 79 and 413 footnote 186.

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art pp. 95–96

- "St Augustine's Gospels" Grove Dictionary of Art

- Wilson Anglo-Saxon Art p. 94

- Sisam "Canterbury, Lichfield, and the Vespasian Psalter" Review of English Studies p. 1

- Colgrave "Introduction" Earliest Life of Gregory the Great pp. 27–28

- Lapidge Anglo-Saxon Library pp. 24–25

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art p. 123

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury p. 23

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 49–50

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art p. 64

- Fryde, et al Handbook of British Chronology p. 221

- Blair Church in Anglo-Saxon Society p. 66

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art p. 232

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 169

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury p. 92

- Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 42

- Williams Kingship and Government p. 58

- Quoted in Williams Kingship and Government p. 58

- Williams Kingship and Government p. 61

References

- Bede (1988). A History of the English Church and People. Sherley-Price, Leo (translator). New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044042-3.

- Blair, John P. (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.

- Blair, Peter Hunter; Blair, Peter D. (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53777-3.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury: Christ Church from 597 to 1066. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-0041-2.

- Brown, Peter G. (2003). The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A. D. 200–1000. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-22138-8.

- Campbell, James (1986). "Observations on the Conversion of England". Essays in Anglo-Saxon History. London: Hambledon Press. pp. 69–84. ISBN 978-0-907628-32-3.

- Chaney, William A. (1967). "Paganism to Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England". In Thrupp, Sylvia L. (ed.). Early Medieval Society. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. pp. 67–83. OCLC 479861.

- Church, S. D. (April 2008). "Paganism in Conversion-age Anglo-Saxon England: The Evidence of Bede's Ecclesiastical History Reconsidered". History. 93 (310): 162–180. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.2008.00420.x.

- Coates, Simon (February 1998). "The Construction of Episcopal Sanctity in early Anglo-Saxon England: the Impact of Venantius Fortunatus". Historical Research. 71 (174): 1–13. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.00050.

- Colgrave, Bertram (2007) [1968]. "Introduction". The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great (Paperback reissue ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31384-1.

- Collins, Roger (1999). Early Medieval Europe: 300–1000 (Second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21886-7.

- Dales, Douglas (2005). ""Apostles of the English": Anglo-Saxon Perceptions". L'eredità spirituale di Gregorio Magno tra Occidente e Oriente. Verona: Il Segno Gabrielli Editori. ISBN 978-88-88163-54-3.

- Deanesly, Margaret; Grosjean, Paul (April 1959). "The Canterbury Edition of the Answers of Pope Gregory I to St Augustine". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 10 (1): 1–49. doi:10.1017/S0022046900061832.

- Demacopoulos, George (Fall 2008). "Gregory the Great and the Pagan Shrines of Kent". Journal of Late Antiquity. 1 (2): 353–369. doi:10.1353/jla.0.0018.

- Dodwell, C. R. (1985). Anglo-Saxon Art: A New Perspective (Cornell University Press 1985 ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9300-3.

- Dodwell, C. R. (1993). The Pictorial Arts of the West: 800–1200. Pellican History of Art. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06493-3.

- Fletcher, R. A. (1998). The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity. New York: H. Holt and Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-2763-1.

- Foley, W. Trent; Higham, Nicholas. J. (May 2009). "Bede on the Britons". Early Medieval Europe. 17 (2): 154–185. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00258.x.

- Frend, William H. C. (2003). "Roman Britain, a Failed Promise". In Carver, Martin (ed.). The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe AD 300–1300. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 79–92. ISBN 978-1-84383-125-9.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56350-5.

- Gameson, Richard and Fiona (2006). "From Augustine to Parker: The Changing Face of the First Archbishop of Canterbury". In Smyth, Alfred P.; Keynes, Simon (eds.). Anglo-Saxons: Studies Presented to Cyril Roy Hart. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 13–38. ISBN 978-1-85182-932-3.

- Herrin, Judith (1989). The Formation of Christendom. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00831-8.

- Higham, N. J. (1997). The Convert Kings: Power and Religious Affiliation in Early Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4827-2.

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2006). A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons: The Beginnings of the English Nation. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1738-5.

- John, Eric (1996). Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5053-4.

- Jones, Putnam Fennell (July 1928). "The Gregorian Mission and English Education". Speculum. 3 (3): 335–348. doi:10.2307/2847433. JSTOR 2847433.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24211-0.

- Kirby, D. P. (1967). The Making of Early England (Reprint ed.). New York: Schocken Books. OCLC 399516.

- Lapidge, Michael (2006). The Anglo-Saxon Library. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926722-4.

- Lapidge, Michael (2001). "Laurentius". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Lawrence, C. H. (2001). Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40427-4.

- Markus, R. A. (April 1963). "The Chronology of the Gregorian Mission to England: Bede's Narrative and Gregory's Correspondence". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 14 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1017/S0022046900064356.

- Markus, R. A. (1970). "Gregory the Great and a Papal Missionary Strategy". Studies in Church History 6: The Mission of the Church and the Propagation of the Faith. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 29–38. OCLC 94815.

- Markus, R. A. (1997). Gregory the Great and His World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58430-2.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (2004). "Augustine (St Augustine) (d. 604)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 March 2008. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1991). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00769-4.

- McGowan, Joseph P. (2008). "An Introduction to the Corpus of Anglo-Latin Literature". In Pulsiano, Philip; Treharne, Elaine (eds.). A Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature (Paperback ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 11–49. ISBN 978-1-4051-7609-5.

- Meens, Rob (1994). "A Background to Augustine's Mission to Anglo-Saxon England". In Lapidge, Michael (ed.). Anglo-Saxon England 23. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–17. ISBN 978-0-521-47200-5.

- Nelson, Janet L. (2006). "Bertha (b. c.565, d. in or after 601)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 March 2008. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Ortenberg, Veronica (1965). "The Anglo-Saxon Church and the Papacy". In Lawrence, C. H. (ed.). The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages (1999 reprint ed.). Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. pp. 29–62. ISBN 978-0-7509-1947-0.

- Schapiro, Meyer (1980). "The Decoration of the Leningrad Manuscript of Bede". Selected Papers: Volume 3: Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 199 and 212–214. ISBN 978-0-7011-2514-1.

- Sisam, Kenneth (January 1956). "Canterbury, Lichfield, and the Vespasian Psalter". Review of English Studies. New Series. 7 (25): 113–131. doi:10.1093/res/VII.25.1. JSTOR 511836.

- Spiegel, Flora (2007). "The 'tabernacula' of Gregory the Great and the Conversion of Anglo-Saxon England". Anglo-Saxon England. 36: 1–13. doi:10.1017/S0263675107000014.

- "St Augustine Gospels". Grove Dictionary of Art. Art.net. 2000. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thacker, Alan (2001). "Chester". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Thacker, Alan (March 1998). "Memorializing Gregory the Great: The Origin and Transmission of a Papal Cult in the 7th and early 8th centuries". Early Medieval Europe. 7 (1): 59–84. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00018.

- Walsh, Michael J. (2007). A New Dictionary of Saints: East and West. London: Burns & Oates. ISBN 978-0-86012-438-2.

- Williams, Ann (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England c. 500–1066. London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 978-0-333-56797-5.

- Wilson, David M. (1984). Anglo-Saxon Art: From the Seventh Century to the Norman Conquest. London: Thames and Hudson. OCLC 185807396.

- Wood, Ian (2000). "Augustine and Aidan: Bureaucrat and Charismatic?". In Dreuille, Christophe de (ed.). L'Église et la Mission au VIe Siècle: La Mission d'Augustin de Cantorbéry et les Églises de Gaule sous L'Impulsion de Grégoire le Grand Actes du Colloque d'Arles de 1998. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf. ISBN 978-2-204-06412-5.

- Wood, Ian (January 1994). "The Mission of Augustine of Canterbury to the English". Speculum. 69 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2864782. JSTOR 2864782.

- Yorke, Barbara (2006). The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c. 600–800. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-77292-2.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16639-3.

Further reading

- Brooks, N. P. (2008). "Gregorian mission (act. 596–601)" ((subscription or UK public library membership required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2008 revised ed.). Oxford University Press.