Ightham Mote

Ightham Mote (/ˈaɪtəm ˈmoʊt/), Ightham, Kent is a medieval moated manor house. The architectural writer John Newman describes it as "the most complete small medieval manor house in the county".[1] Ightham Mote and its gardens are owned by the National Trust and are open to the public. The house is a Grade I listed building, and parts of it are a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

| Ightham Mote | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | House |

| Location | Ightham, Kent |

| Coordinates | 51.2585°N 0.2698°E |

| Built | Medieval |

| Architect | unknown |

| Architectural style(s) | Vernacular |

| Governing body | National Trust |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name: Ightham Mote | |

| Designated | 1 August 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1362410 |

Location of Ightham Mote in Kent | |

History

14th century–16th century

The origins of the house date from circa 1340-1360.[2] The earliest recorded owner is Sir Thomas Cawne, who was resident towards the middle of the 14th century.[1] The house passed by the marriage of his daughter Alice to Nicholas Haute and their descendants, their grandson Richard Haute being Sheriff of Kent in the late 15th century.[1] It was then purchased by Sir Richard Clement in 1521.[1] In 1591, Sir William Selby bought the estate.[1]

16th century-late 19th century

The house remained in the Selby family for nearly 300 years.[3] Sir William was succeeded by his nephew, also Sir William, who is notable for handing over the keys of Berwick-upon-Tweed to James I on his way south to succeed to the throne.[4] He married Dorothy Bonham of West Malling but had no children. The Selbys continued until the mid-19th century when the line faltered with Elizabeth Selby, the widow of a Thomas who disinherited his only son.[5] During her reclusive tenure, Joseph Nash drew the house for his multi-volume illustrated history Mansions of England in the Olden Time, published in the 1840s.[6] The house passed to a cousin, Prideaux John Selby, a distinguished naturalist, sportsman and scientist. On his death in 1867, he left Ightham Mote to a daughter, Mrs Lewis Marianne Bigge. Her second husband, Robert Luard, changed his name to Luard-Selby. Ightham Mote was rented-out in 1887 to American Railroad magnate William Jackson Palmer and his family. For three years Ightham Mote became a centre for the artists and writers of the Aesthetic Movement with visitors including John Singer Sargent, Henry James, and Ellen Terry. When Mrs Bigge died in 1889, the executors of her son Charles Selby-Bigge, a Shropshire land agent, put the house up for sale in July 1889.[6]

Late 19th century-21st century

The Mote was purchased by Thomas Colyer-Fergusson.[6] He and his wife brought up their six children at the Mote. In 1890-1891, he carried out much repair and restoration, which allowed the survival of the house after centuries of neglect.[7] Ightham Mote was opened to the public one afternoon a week in the early 20th century.[7]

Sir Thomas Colyer-Fergusson's third son, Riversdale, died aged 21 in 1917 in the Third Battle of Ypres, and won a posthumous Victoria Cross. A wooden cross in the New Chapel is in his memory. The oldest brother, Max, was killed at the age of 49 in a bombing raid on an army driving school near Tidworth in 1940 during World War II. One of the three daughters, Mary (called Polly) married Walter Monckton.

On Sir Thomas's death in 1951, the property and the baronetcy passed to Max's son, James. The high costs of upkeep and repair of the house led him to sell the house and auction most of the contents. The sale took place in October 1951 and lasted three days. It was suggested that the house be demolished to harvest the lead on the roofs, or that it be divided into flats. Three local men purchased the house: William Durling, John Goodwin and John Baldock. They paid £5,500 for the freehold, in the hope of being able to secure the future of the house.[8]

In 1953, Ightham Mote was purchased by Charles Henry Robinson, an American of Portland, Maine, United States. He had known the property when stationed nearby during the Second World War. He lived there for only fourteen weeks a year for tax reasons. He made many urgent repairs, and partly refurnished the house with 17th-century English pieces. In 1965, he announced that he would give Ightham Mote and its contents to the National Trust. He died in 1985 and his ashes were immured just outside the crypt. The National Trust took possession in that year.[8]

In 1989, the National Trust began an ambitious conservation project that involved dismantling much of the building and recording its construction methods before rebuilding it. During this process, the effects of centuries of ageing, weathering, and the destructive effect of the deathwatch beetle were highlighted. The project ended in 2004 after revealing numerous examples of structural and ornamental features which had been covered up by later additions.[1] The final year of construction was followed by the television series Time Team.[9]

Architecture and description

Originally dating to around 1320, the building is important because it has most of its original features; successive owners effected relatively few changes to the main structure, after the completion of the quadrangle with a new chapel in the 16th century. Pevsner described it as "the most complete small medieval manor house in the county", and it remains an example that shows how such houses would have looked in the Middle Ages. Unlike most courtyard houses of its type, which have had a range demolished, so that the house looks outward, Nicholas Cooper observes that Ightham Mote wholly surrounds its courtyard and looks inward, into it, offering little information externally.[10] The construction is of "Kentish ragstone and dull red brick,"[11] the buildings of the courtyard having originally been built of timber and subsequently rebuilt in stone.[12]

The house has more than 70 rooms, all arranged around a central courtyard, "the confines circumscribed by the moat."[11] The house is surrounded on all sides by a square moat, crossed by three bridges. The earliest surviving evidence is for a house of the early 14th century, with the Great Hall, to which were attached, at the high, or dais end, the Chapel, Crypt and two Solars. The courtyard was completely enclosed by increments on its restricted moated site, and the battlemented tower was constructed in the 15th century. Very little of the 14th century survives on the exterior behind rebuilding and refacing of the 15th and 16th centuries.

The structures include unusual and distinctive elements, such as the porter's squint, a narrow slit in the wall designed to enable a gatekeeper to examine a visitor's credentials before opening the gate. An open loccia with a fifteenth-century gallery above, connects the main accommodations with the gatehouse range. The courtyard contains a large, 19th century dog kennel.[13] The house contains two chapels; the New Chapel, of c.1520, having a barrel roof decorated with Tudor roses. [14] Parts of the interior were remodelled by Richard Norman Shaw.[15]

Grounds

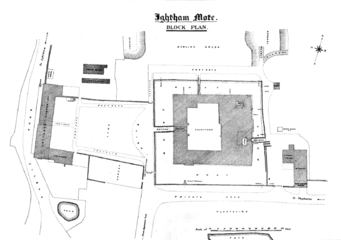

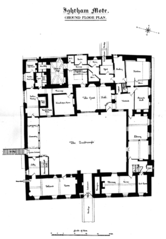

Grounds Ground floor plan of main building

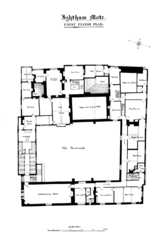

Ground floor plan of main building First floor plan

First floor plan

References

- Newman 2012, p. 320.

- "IGHTHAM MOTE - 1362410". Historic England. 1952-08-01. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- Nicolson 1998, p. 38.

- Nicolson 1998, p. 39.

- Nicolson 1998, p. 40.

- Nicolson 1998, p. 41.

- Nicolson 1998, p. 42.

- Nicolson 1998, p. 45.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4B9WPT5gyNk

- Cooper 1999, p. 65.

- Cook 1984, p. 41.

- Wood 1996, p. 155.

- "IGHTHAM MOTE - 1362410". Historic England. 1952-08-01. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- Wood 1996, p. 240.

- Good Stuff (1952-08-01). "Ightham Mote, Ightham, Kent". Britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

Sources

- Cook, Olive (1984). The English House Through Seven Centuries. London: Penguin. ISBN 9780140067385.

The English House Through Seven Centuries.

- Cooper, Catriona Elizabeth (2014). The exploration of lived experience in medieval buildings through the use of digital technologies (PDF). université de Southampton.

- Cooper, Nicholas (1999). Houses of the Gentry 1480-1680. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300073904. OCLC 890145910.

- Newman, John (2012). Kent: West and The Weald. The Buildings of England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300185096.

- Nicolson, Nigel (1998). Ightham Mote. London: The National Trust. ISBN 9781843591511.

- Wood, Margaret (1996). The English Medieval House. London: Studio Editions. ISBN 9781858911670. OCLC 489870387.

Further reading

- Christopher Simon Sykes, Ancient English Houses 1240-1612 (London: Chatto & Windus) 1988

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ightham Mote. |