Bayons

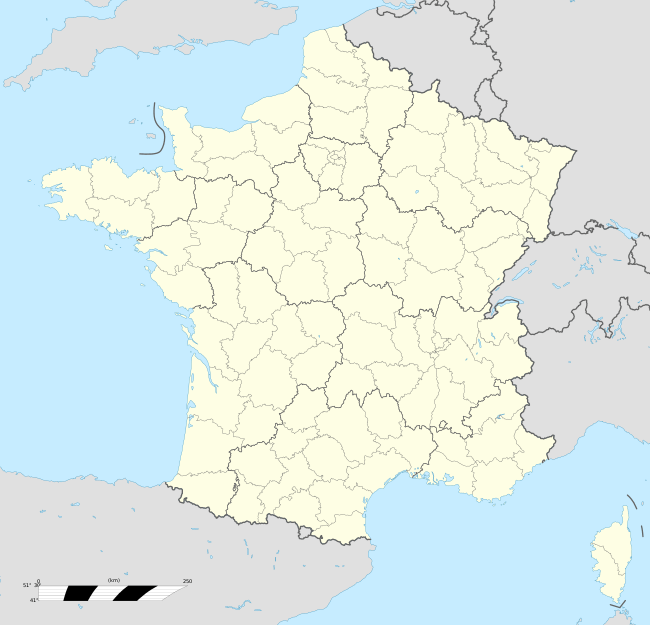

Bayons (Occitan: Baion) is a commune in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of south-eastern France.[2]

Bayons | |

|---|---|

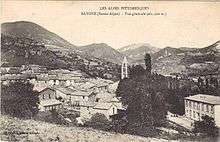

The crest of the Clos de Fau opposite the village. | |

Coat of arms | |

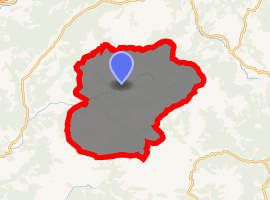

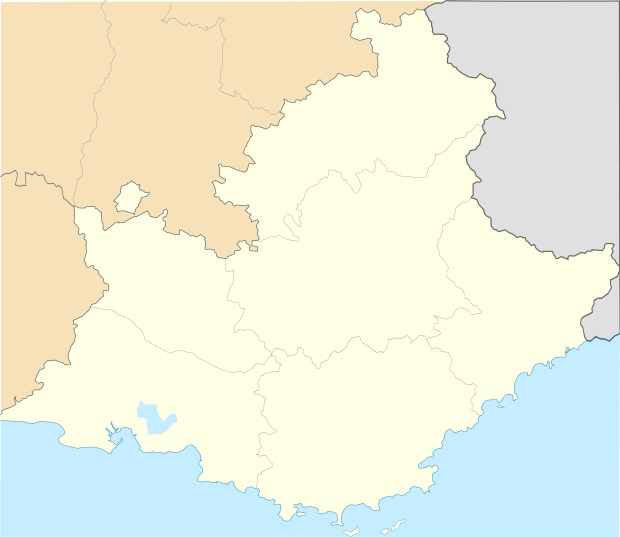

Location of Bayons

| |

Bayons  Bayons | |

| Coordinates: 44°20′23″N 6°09′51″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur |

| Department | Alpes-de-Haute-Provence |

| Arrondissement | Forcalquier |

| Canton | Seyne |

| Intercommunality | Community of communes of la Motte-Turriers |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2014–2020) | Patrick Auriault |

| Area 1 | 125.75 km2 (48.55 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 183 |

| • Density | 1.5/km2 (3.8/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 04023 /04250 |

| Elevation | 749–2,111 m (2,457–6,926 ft) (avg. 870 m or 2,850 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

The inhabitants of the commune are known as Bayonnais or Bayonnaises.[3]

Geography

Bayons is located in the Massif des Monges some 20 km south by south-east of Gap and 15 km north-east of Sisteron. Access to the commune is by the D1 road from Clamensane in the west which passes through the commune and the village before continuing north to Turriers.[4][5]

Bayons is situated in a vast Cirque surrounded by high mountains, through which the Sasse flows - exiting through a narrow clue. The commune was formed from the merger of four communes in 1973: Astoin, Bayons, Esparron-la-Bâtie and Reynier. Except for Astoin, the communes joined to Bayons in 1973 are located in parallel valleys perpendicular to the Sasse and downstream from Bayons.[6] The commune is located in a region of mountainous relief and has a Mediterranean climate with challenging features (drought, irregular and heavy rains) as well as a mountain climate (cold with snow in winter). It is traversed by some tumultuous rivers. Agriculture in the area has always been difficult. The population of the four communes peaked in 1836 with 1625 inhabitants but a century and a half later, 90% of this population had been lost due to the rural exodus that began early and had more breadth in these four communes than in the rest of the department. This persuaded the government to propose the merger of the communes which took place on 1 April 1973. Since then the population has almost doubled: farms have been retained sometimes using regional quality labels. The communal economy is based on tourism but the majority of people in the commune work outside.

Geology

The commune is located in the middle of three major geological Alpine formations:[7]

- the Nappe of Digne to the east[8] at the tip of the Valavoire lobe:[9] there is a thrust sheet - i.e. a slab nearly 5000 m thick which was displaced towards the south-west during the Oligocene at the end of the formation of the Alps. The lobes (or scales) correspond to the ragged edge west of the nappe;

- the Durance fault to the south-west in the valley;

- the Plateau of Valensole to the south-east: a Molassic Basin from the Miocene and Pliocene composed of detritic sedimentary rocks (deposits related to the erosion of mountains which emerged in the Oligocene).

During the last two major glaciations: the Riss glaciation and the Würm glaciation, there were many small glaciers in the commune. A glacier occupied the northern slope of the Tête des Monges. During the Riss glaciation, a diffluence from the Durance glacier crossed the Col des Sagnes and went down to the Sasse valley. The Würm glaciation was less extensive and only reached Les Tourniquets. It was during this glacial period that the Triassic gypsum and moraines were created that make the terrain unstable in this part of the valley. Another Riss glaciation diffluence reached the top of the Trente Pas torrent but this did not recur during the Würm glaciation.[10]

Relief

The relief of the commune is mountainous, low, but very compartmentalized making communication difficult. It has partly been shaped by glaciers. The main structural element is the Sasse valley, which drains several basins separated by Water gaps.[10]

The southernmost of these basins is the former commune of Reynier, semi-circular in shape with the diameter towards the north-east. This diameter is a ridge of mountains rising between 1200 m and 1700 m separating the Reynier basin from the Esparron-la-Bâtie valley. From north to south:[5]

- the Pategue (1282 m);

- the Charène Ridge;

- Colle Ridge;

- the Citadelle (1438m);

- the Pinée ridge (>1600m);

- the Maladrech Ridge (>1700m) to the south-east.

Several mountains then define a wide semicircle. On the north side (the side facing Reynier) they slope gently and form green mountain meadows. On the south and west side they form a line of steeper slopes. From east to west and from south to north they are:[5]

- the Raus Ridge (1832 m);

- the Serrière des Cabanes;

- the Clot des Martres Ridge;

- the Dormeilleuse Ridge which rises to the Croix Saint-Jean (1826m) when it connects to Jouère mountain;

- the Jouère mountain whose peak extends towards the Reynier mountain. This mountain forms a basin to the north, along the Sasse. In the middle of this basin is Le Puy (1367m): another mountain with a ridge in the south and an inclined slope to the north.

North of Reynier basin, the Bayons gorge provides access to the upper valley of the Sasse and the Bayons basin. This basin is bounded on the north by a small massif dominated by Pointe d'Eyrolle (1754m) and Grande Gautière (1825m) which opens to several valleys in the east and south:[5]

- to the north is the valley where Astoin is located and which communicates with the Turriers basin through a gorge - the Col des Sagnes (1182 m) - and Les Tourniquets;

- Trente Pas and Sasse valleys are to the north-east limited by the summits of Terre Grosse (1598m), Tête de Charbonnier (1681m), Tête Grosse (2032m), and Chanau (1885m).

Facing Bayons, is l'Oratoire summit (2072 m).Tête Grosse

Finally, wedged between the Bayons basin and that of Reynier, is the long valley of Esparron-la-Bâtie Sasse closed off from the Sasse by the Rochers de la Lause. The ridges north of this valley are led to the top of l'Oratoire and are marked by the Rocher de l'Aigle (1499m) and the Rocher du Midi (1461m). This valley widens and is closed to the east by the Summit of Clot Ginoux (also called the Cimettes) (2112m), the summit of Laupie (or Tourtoureau) (2025m), and the summit of Les Monges (2115m).[5]

Hydrography

The commune is traversed by the Sasse[11] (sometimes called La Sasse[12]), which is formed from many streams and has many tributaries draining the adjacent valleys. On the right bank the Sasse receives:[5]

- the stream from the Trente Pas ravine;

- the Eau Amère stream which becomes the Clastre when traversing Les Tourniquets;

- the Mardaric, which passes at the foot of Bayons;

- the Rouinon, whose confluence with the Sasse is between Forest-Lacour and Bédoin.[13]

The left bank tributaries of the Sasse are:[5]

- the Chabert, a stream 5.5 km long flowing through the Bayons basin;[14]

- the Riou de Pont, which drains the Esparron-la-Bâtie valley and, when crossing the Rochers de la Lause, forms a waterfall and becomes the Ruisseau des Tines, a stream 10 km long;[15]

- the Reynier, a stream 9.1 km long.[16]

In the upper part of the Esparron-la-Bâtie valley is a small lake, Lake Esparron at 1544m, to the east of the Maladrech ridge.[5]

Environment

The town has 5500 hectares of woods and forests or 44% of its area.[17]

Chamois are endemic in the Massif of Monges but had nearly disappeared from the area in the 1970s as victims of intensive hunting. The National Forests Office (ONF) has created a game reserve in the Haute Combe which includes the reserves of Monges, Hautes-Graves-Ruinon, and Montsérieux. Since the 1980s the species is still hunted but with quotas.[18]

The Mouflon had been exterminated and its presence is due to its reintroduction in early 1990. Two population nuclei are in the commune: in the hunting reserve of the Hautes-Graves-Ruinon and in the Massif des Monges. Roe Deer had also disappeared since the beginning of the 19th century together with its natural environment the forest. It has returned to the commune from a core reintroduced into the Vançon valley in the 1970s. The presence of the Alpine marmot is also mainly due to reintroductions. The otter, which was once present, has disappeared but has not been reintroduced.[18]

Natural and technological risks

None of the 200 communes in the department is in a no seismic risk zone. The Canton of Turriers to which Bayons belongs is in area 1b (low risk) according to the deterministic classification of 1991 and based on its seismic history and in zone 4 (medium risk) according to the probabilistic classification EC8 of 2011. Bayons also faces four other natural hazards:[19]

- Avalanche

- Forest fire

- Flood

- Landslide

Bayons is not exposed to any risk of technological origin identified by the prefecture.[19]

There is no plan for prevention of foreseeable natural risks (PPR) for the commune and there is no DICRIM.[19]

The commune has been the subject of orders for natural disasters in 1994 for floods, landslides and mudslides.[19] The worst flooding occurred in 1492 when rains caused the formation of debris flows that destroyed several hamlets and part of the village. This monstrous flood has remained in the annals of the commune.[20] See the History section for details.

Localities and hamlets

In addition to the village, the town includes several hamlets:[5]

- Astoin (chief village of a former commune);

- Haute Combe;

- Basse Combe;

- La Rouchaye;

- Esparron-la-Bâtie (chief village of a former commune);

- Le Pont;

- Baudinard;

- Le Gayne;

- Le Sapie;

- Le Forest-Lacour;

- Reynier (chief village of a former commune).

Pictures of roads and bridges in the commune

- The Reynier bridge.

- The bends of the D1 crossing a Water gap at les Tourniquets.

- A trap protecting from falling rocks.

- The Bayons water gap.

History

Prehistory and Ancient times

Although Homo heidelbergensis probably inhabited the Monges massif several hundreds of thousands of years ago there is no evidence that they specifically occupied the area of Bayons. The Vitrolles site, 30 km to the west, shows that 11,000 years ago the area was frequented by hunters and gatherers who came in summer then went away to the south.[21]

Most of the Durance valleys and the Massif des Monges experienced the Neolithic Revolution when Mesolithic societies disappeared and were replaced by Cardium pottery (6000 BC.) and then by the Chasséen culture (4700-3500 BC). The Lithic core found at Thèze was an example of the technical progress in the era: stone tools are no longer cut by impact but by pressure applied on the chosen part.[21]

A treasure of Massaliatic obols dating from the Gallic period (3rd and 2nd century BC.) was discovered in the commune in 1850. The romanization of Bayons in the following centuries is manifested by constructions at altitude.[22]

Middle Ages

Astoin

The castrum of Astoin was near the mule track connecting Bayons to Turriers.[22]

The Counts of Provence were lords of Astoin during the 14th and 15th century through the Ayroles and Ancelle families (co-lord of Dromon in 1385).[22] During the crisis caused by the death of Queen Joanna I of Naples, Raoux Ancelle, Lord of Astoin, fought with Charles, Duke of Durazzo, against Louis I of Anjou. The rallying of Sisteron to the Angevin cause in November 1385 brought about his change of commitment and he paid homage to Louis from 30 November 1385.[23]

Astoin had 28 fires in 1315 but only 6 in 1471.[24] It was at that time that the old site, located on a hill 500 m from the current site and named Vière (Old Provençal meaning "village"), was abandoned in favour of the current site.[6] By 1765 there were 264 inhabitants.[24]

Bayons

Bayons is cited around 1200 in the form Baions.[24] The community had a consulate in 1233 and was the largest community in the viguerie of Sisteron. The two churches and their income belonged to the Abbey of l'Ile-Barbe in Lyon. The oldest church was the Church of Our Lady of Nazareth which was located in the Clastre valley, probably on the medieval site of the village. The community owned the lands called gastes which also belonged to the lord. These lands were farmed by the community often as pasture. At Bayons, they were traditionally granted against a tasque equivalent to one eighth of the harvest. The income of the community allowed it to gradually redeem all manorial rights before 1789 including the privilege granted by the counts of Provence banning the grazing of foreign herds (from outside the commune) in Bayons lands. The Counts of Provence also levied a toll on cattle migrations passing through Bayons.[6][22][24]

In 1300 a small Jewish community was established in Bayons which is an indication of its position as a tiny relatively unknown rural hamlet. In 1348 Queen Joanna I of Naples, driven from her Kingdom of Naples, had to take refuge in Provence. To regain her Neapolitan States she sold Avignon to the Pope for 80,000 florins and at the same time obtained papal absolution to wash away suspicion in the murder of her first husband Andrew, Duke of Calabria. Grateful, she offered the fief of Valernes to William II Roger, brother of the pope. This was made a viscounty by letters patent in 1350. The new viscounty included the communities of Bayons, Vaumeilh, La Motte-du-Caire, Bellaffaire, Gigors, Lauzet, Les Mées, Mézel, Entrevennes, and Castellet, with their jurisdictions and dependencies.[25][26][27]

In 1359 the residents of Bayons sued those of Seyne, claiming the privilege of not paying the toll to come to the fair at Saint-Michel de Seyne. They obtained satisfaction but the people of Seyne won on appeal. Fortifications were built in the 14th century which were inspected in 1403 by the provost of the Viscount of Valernes. Another fortification was built above Bédoin on the mountain called the Chateau: it allowed the monitoring of the road from Sisteron to Seyne.[22]

On 26 July 1492 heavy rains cause a devastating flood of the Sasse. Le Mardaric, the torrent passing Bayons, had a debris flow that destroyed the village. The hamlets of la Montahne (identified with that of Combes) and Rouinon were also affected Rouinon. The Fontainier torrent also caused damage to cultivated land. Four people were killed. Livestock was also affected with hundreds of animals washed away. Finally loosened soils were washed away by rain together with ripe wheat and vines in the following days. According to residents rocks of 5 tons were displaced by the floods.[6][22]

Esparron-la-Bâtie

The village of Esparron was cited in 1200 under the name of castrum Sparronis et bastita. There were two village communities, and one fief held by a lord. Esparron-la-Bâtie was hardest hit by the crises of the 14th century (the Black Death and the Hundred Years War) than its neighbours, as it had 74 fires in 1315 but only 12 in 1471. By 1765 it had a population of 205. The Counts of Provence levied a toll on cattle migrations passing through Esparron-la-Bâtie and lords were the Morier or Mourier family from the 13th to the 17th Century. The parish church was heavily damaged by the end of the religious wars. In 1641 repairs had still not been done and the lord of Esparron was ordered to pay for two thirds of the work with the remaining third by the priory.[6][22][24][28]

Reynier

Reynier is reported for the first time in charters of 1232 as castrum Rainieri. The community had 25 fires in 1471 and 218 inhabitants by 1765. This former fief of the Bishops of Gap was owned by the Abon family from the 15th to the 17th century then by the Boniface family until the French Revolution.[6][22][24]

Modern times

From the 16th century the lordship of Astoin belonged successively to Turriers, Castellane, Boniface, then to Hugues. At Esparron the Pélissier family succeeded Mourier in the 17th century.[22]

In the 16th century Louis de Barras, Lord of Melan, allowed the grazing of sheep flocks in Bayons from Estiver (against payment of a fee), while herds from Reynier and Esparron-la-Bâtie wintered at La Roque and Corbières.[29]

- Bayons appears as Bayons on the 1750 Cassini Map[30] and the same on the 1790 version.[31]

- Astoin appears as Aftoin on the 1750 Cassini Map[30] and as Astoin on the 1790 version.[31]

- Esparron-la-Bâtie appears as Efparron on the 1750 Cassini Map[30] and as Esparron on the 1790 version.[31]

- Reynier appears as Reynier on the 1750 Cassini Map[30] and the same on the 1790 version.[31]

French Revolution

At the beginning of the French Revolution, the news of the storming of the Bastille was welcomed but caused a phenomenon of collective fear in the population of a possible aristocratic reaction. Locally, the Great Fear came from Tallard and belonging to the contemporary fear of the Mâconnais reached the area of La Motte-du-Caire on the evening of 31 July 1789. The consuls of the village community were warned that a troop of five or six thousand brigands were coming towards Haute-Provence after pillaging the Dauphiné. The communities of La Motte, Clamensane, Saint-Geniez, Authon, Curbans, Bayons, and Claret together created a troop of 700 armed men. They put the Marquis of Hugues de Beaujeu at its head. He decided to stand in front of the danger by going towards the danger and to monitor the boats on the Durance.[32]

After 2 August the panic subsided and the original rumours clarified. An important change took place: the communities were armed and organized to defend themselves and their neighbours. A sense of solidarity was born within the communities and between neighbouring communities and consuls decide to maintain the national guards. Immediately after the fear subsided, however, the authorities recommended disarming the workers and the landless and keep only landowners in the National Guard.[32]

Contemporary period

The French coup d'état of 1851 committed by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte against the French Second Republic provoked an armed uprising in the Lower Alps in defense of the Constitution. After the failure of the uprising there was a severe crackdown on those who stood up to defend the Republic with one inhabitant of Bayons.[33]

Like many communes in the department, Bayons adopted schools well before the Jules Ferry laws: in 1863 there were already two schools providing primary education for boys located in the main village and at Combe. Although the Falloux Laws (1851) did not require the opening of a school for girls in communes with less than 800 inhabitants, Bayons, with less than 700 inhabitants in 1861, also had a school for girls. The second Duruy Act (1877) allowed it, thanks to government subsidies, to build new village school.[34]

Astoin, Esparron-la-Bâtie, and Reynier communes each had a boys' school in 1863 but no school for girls. In these communes it was not the Ferry laws that allowed girls into school.[34]

The very isolated hamlet of Rouinon had 46 inhabitants in 1886 as well as a school (until 1911) and a mailbox (until 1929). This small community also had its own Chapel of Saint Joseph. Near Rouinon, the chapel for the hamlet of Forest-Lacour was destroyed at the end of the 19th century to allow the passage of the road: the Church had noted its declining attendance for several years.[6][22]

The commune sheltered a maquis unit during World War II in the Tramalou district. It consisted of Francs-tireurs partisans (Maverick Partisans) or FTP. On 21 July 1944, taking advantage of a shift in the German garrison of Sisteron, the Bayons FTP raided the citadel of Sisteron to rescue fifty resistance fighter detainees. On 26 July 1944, the same FTP unit was surprised by the German reaction using mortars which resulted in 21 dead. Three teenagers in a farm were also killed. A monument was erected in their memory located on an abandoned road to Turriers.[35]

Since World War II

Vines were cultivated in the communes of Astoin, Bayons, Esparron-la-Bâtie and Reynier until the middle of the 20th century. The wine was mediocre and intended only for home consumption. This culture has since been abandoned.[36]

The commune of Bayons merged with the communes of Esparron-la-Bâtie, Astoin, and Reynier in 1973.[37]

Heraldry

Arms of Bayons |

Blazon: Azure, a fess Argent charged with the word BAYONS in capitals of Sable, surmounted by another fess Argent, in base 2 mullets of Or. |

Politics and administration

Municipal Administration

The Municipal Council is composed of 9 members including the Mayor.[38]

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | Arthur Daumas[40] | |||

| 1948 | 1952 | Louis Aimé Estellon | ||

| 2001 | 2014 | Bernard Daumas | ||

| 2014 | 2020 | Patrick Auriault |

(Not all data is known)

Judicial and administrative proceedings

Bayons falls within the area of the Tribunal d'instance (District court) of Digne-les-Bains, the Tribunal de grande instance (High Court) of Digne-les-Bains, the Cour d'appel (Appeal court) of Aix-en-Provence, the Tribunal pour enfants (Juvenile court) of Digne-les-Bains, the Conseil de prud'hommes (Labour Court) of Digne-les-Bains, the Tribunal de commerce (Commercial Court) of Manosque, the Tribunal administratif (Administrative tribunal) of Marseille, and the Cour administrative d'appel (Administrative Court of Appeal) of Marseille[41]

Budget and Taxation

| Tax | Communal portion | Inter-communal portion | Departmental portion | Regional portion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing Tax (TH) | 3.80% | 0.95% | 5.53% | 0.00% |

| Business Land Tax (CFE) | 23.60% | 3.55% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Land value Tax on buildings (TFPB) | 10.35% | 3.35% | 14.49% | 2.36% |

| Land value tax on undeveloped land (TFPNB) | 64.00% | 6.44% | 47.16% | 8.85% |

| Transfer taxes | 1.20% | 0.00% | 3.60% | 0.00% |

Demography

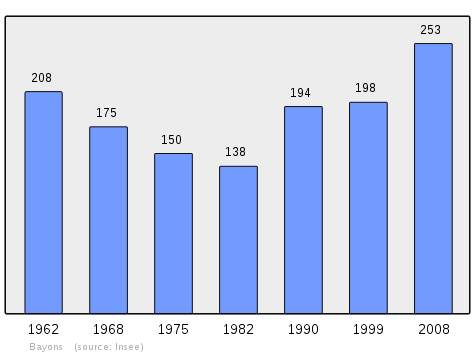

In 2012 the commune had 232 inhabitants. The evolution of the number of inhabitants is known from the population censuses conducted in the commune since 1793. From the 21st century, a census of communes with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants is held every five years, unlike larger communes that have a sample survey every year.[Note 1]

| 1793 | 1800 | 1806 | 1821 | 1831 | 1836 | 1841 | 1846 | 1851 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 748 | 772 | 705 | 729 | 804 | 876 | 854 | 908 | 793 |

| 1856 | 1861 | 1866 | 1872 | 1876 | 1881 | 1886 | 1891 | 1896 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 685 | 678 | 719 | 681 | 660 | 629 | 619 | 602 | 567 |

| 1901 | 1906 | 1911 | 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | 1946 | 1954 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 540 | 501 | 461 | 420 | 433 | 320 | 269 | 208 | 183 |

| 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2007 | 2012 | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 136 | 128 | 150 | 138 | 194 | 198 | 255 | 232 | - |

Economy

Overview

In 2012 the workforce was 83 people, including 11 unemployed. These people are mostly employees (88%) and many work outside the commune (33%).[43] On 1 January 2014 there were a total of 28 business enterprises in the commune: 7 in Agriculture, 4 in Industry, 1 in construction, 12 in Trade, transport, and services, and 4 in Administration, education, health, or social services. Only the tertiary sector employed staff with 6 employees.[44]

Agriculture

According to the Agreste survey by the Ministry of Agriculture the number of farms dropped sharply in the 2000s from 17 to 10. Sheep farms represented half of these farms. From 1988 to 2000 the agricultural land area (SAU) increased from 1100 hectares to 1216 while the number of farms fell from 20 to 17. The SAU has continued to increase during the last decade reaching 1352 hectares including 720 dedicated to sheep farming.[45]

Farms practicing polyculture disappeared in the 2000s.[45]

Labels

Bayons commune has an Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) for Lavender oil of Haute-Provence and 30 Geographical Protected Indications (IGP) including: Apples of Alpes de Haute-Durance, Honey of Provence, Lamb of Sisteron,[46] and many Méditérranée wine labels.[47]

- Labels of Bayons

- Lamb of Sisteron.

- Lavender honey.

Golden and gala apples.

Golden and gala apples.

Industry

A Small hydro electric power station was installed in the late 1980s on Ruisseau des Tines (old town of Esparron-la-Bâtie).[48]

Service activities

According to the Departmental Observatory of Tourism, tourism is important for the commune with between 1 and 5 tourists accommodated per capita but most of the accommodation capacity is non-market. Several tourist accommodation facilities exist in the commune:

- 1 furnished accommodation with 4 beds

- 1 Bed and Breakfast with 4 beds

- 2 Hostels with 16 beds

It is nevertheless second homes that have the greatest capacity with 160 second homes and a total of 798 beds.[49]

Culture and heritage

Cultural festivals

On the first Rogation day there is a procession from Bayons to Forest and return.

Civil heritage

Religious heritage

- The Church of Saint Anne at Astoin[24] was the former castrum church dedicated to Saint-Michel. The Parish of Astoin was merged with Bayons in 1711.[22]

- The Church of Saint-Christophe and Saint Sebastian at Esparron.[22][24] The former Church of Saint Vincent de Reynier on the hill is in ruins:[6] it was an old chapel chosen to replace the parish church at the end of the Wars of religion in 1599.[22] It was replaced by another Church of Saint Vincent in 1833.[6]

- The Chapel of Basse Combe was restored in the 2000s.

- The Saint Mary Magdalene Chapel in Haute Combe is in ruins.[6]

- The Chapel Notre-Dame-Secours-des-Pécheurs at Baudinard was built by the inhabitants in 1867-1868 for the new cemetery which replaced the old cemetery which was far away.[6]

- The Church of Notre-Dame-de-Bethléem (11th century)

The vaults were rebuilt several times: the choir in the 14th century and the nave in 1664.[53] Other comprehensive repairs took place from 1664 to 1689 and the tower is repaired in 1724. A clock was added to it in 1742. Many other repairs took place throughout the 20th century and roofs were restored to their original angles in 1995.[22]

The Church contains many items that are registered as historical objects:

- A Cross (Crucifix) (18th century)

- A Chalice (19th century)

- A Cross (Crucifix) (17th century)

- A Painting: Joseph of Léonissa (17th century)

- The main Altar (18th century)

- A Painting: Assumption (17th century)

- A Painting: Death of Saint Joseph (17th century)

- A Painting: Saints Jacques and Peter at the foot of the virgin (17th century)

- The enclosures in the 2 lateral chapels (17th century)

- A Pulpit (17th century)

- 2 Pews (19th century)

- A Statue: Virgin and child (18th century)

- A Painting with frame: Virgin of pity (18th century)

- A Painting: Saint Blaise (1750)

- A Painting: Adoration of the Magi (17th century)

- A Retable: Adoration of the magi (18th century)

- A Bronze bell (1510)

- A Baptismal font (16th century)

Churches Picture gallery

- Church of Saint Anne at Astoin

- Church of Saint-Christophe at Esparron-la-Bâtie.

- Church of Saint-Vincent at Reynier.

- Chapel Saint-Jacques and Saint-Philippe at Basse-Combe.

- Chapel Notre-Dame-Secours-des-Pécheurs at Baudinard.

See also

Bibliography used in this Article

- Raymond Collier, Haute-Provence Monumental and artistic, Digne, Louis Jean Printing, 1986, 559 pages (in French)

- Under the direction of Edward Baratier, Georges Duby, and Ernest Hildesheimer, Historical Atlas. Provence, Venaissin County, Principality of Orange, County of Nice, Principality of Monaco, Paris, Librairie Armand Colin, 1969 BNF FRBNF35450017h (in French)

- Guy Barruol, Nerte Dautier, Bernard Mondon (coord.), Mount Ventoux. Encyclopedia of a Provencal mountain

Bibliography not used in this Article

- Hélène Vésian Claude Gouron, The Way of Liberty - on the passive resistance of Haute-Provence (ISBN 2-906924-32-6)

Notes and references

Notes

- At the beginning of the 21st century, the methods of identification have been modified by Law No. 2002-276 of 27 February 2002 Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, the so-called "law of local democracy" and in particular Title V "census operations" allows, after a transitional period running from 2004 to 2008, the annual publication of the legal population of the different French administrative districts. For communes with a population greater than 10,000 inhabitants, a sample survey is conducted annually and the entire territory of these communes is taken into account at the end of the period of five years. The first "legal population" after 1999 under this new law came into force on 1 January 2009 and was based on the census of 2006.

References

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Bayons on Lion1906

- Inhabitants of Alpes-de-Haute-Provence (in French)

- Bayons on Google Maps

- Bayons on the Géoportail from National Geographic Institute (IGN) website (in French)

- Daniel Thiery, On the origins of churches and rural chapels in Alpes-de-Haute-Provence - Bayons, published 13 December 2010, online 15 December 2010, consulted on 2 July 2012. (in French)

- Maurice Gidon, The ranges of Digne], schematic map showing the relationship between the ranges of the eastern Baronnies (northern part) and those of Digne (southern part), with the precursor country of the nappe of Digne (western part). (in French)

- Geological Map of France at 1:1,000,000 (in French)

- Maurice Gidon, The Nappe of Digne and the connecting structures. (in French)

- Maurice Jorda, Cécile Miramont, "The Highlands: a geomorphological reading of the landscape and its evolution", in Nicole Michel d'Annoville, Marc de Leeuw (directors) (photogr Gerald Lucas, drawing Michel Crespin.), Roaming the High Lands of Medieval Provence, Le Caire: The Association highlands of Provence; Saint-Michel-l'Observatoire, 2008, 223 p., ISBN 978-2-952756-43-3, p. 33-34. (in French)

- Page on the Sasse, SANDRE, consulted on 15 June 2011 (in French).

- The feminine name was mentioned in the master development and water management diagram of the Rhone-Mediterranean basin during its Drainage basin Committee meeting on 16 October 2009.

- Page on the Torrent de Rouinon, SANDRE (in French).

- Page on the Torrent de Chabert, SANDRE (in French)

- Page on the Ruisseau des Tines, SANDRE (in French).

- Page on the Torrent de Reynier, SANDRE (in French).

- Roger Brunet, Canton of Bayons, Le Trésor des régions, consulted on 11 June 2013. (in French)

- Jean-Claude Bouffier, "Wild fauna of Monges in the Durance", in Nicole Michel d'Annoville, Marc de Leeuw (directors) (photogr Gerald Lucas, drawing Michel Crespin.), Roaming the High Lands of Medieval Provence, Le Caire: The Association highlands of Provence; Saint-Michel-l'Observatoire, 2008, 223 p., ISBN 978-2-952756-43-3, p. 19-20. (in French)

- Ministry of Ecology, sustainable development, transport, and lodgings, Communal Notice Bayons Archived 2015-12-23 at the Wayback Machine on the Gaspar database (in French)

- Jean-Pierre Leguay, The Catastrophes of the Middle Ages, Paris, Éditions Jean-Paul Gisserot, 2005, "Les classiques Gisserot de l'histoire" collection. ISBN 2-87747-792-4, (reprinted in 2014). p. 201. (in French)

- Jean Gagnepain, "The Prehistory of the high lands of Provence", in D’Annoville, de Leeuw, opcit, p. 44-45. (in French)

- Marc de Leeuw, "Bayons", in Nicole Michel d'Annoville, Marc de Leeuw (directors) (photogr Gerald Lucas, drawing Michel Crespin.), Roaming the High Lands of Medieval Provence, Le Caire: The Association highlands of Provence; Saint-Michel-l'Observatoire, 2008, 223 p., ISBN 978-2-952756-43-3, p. 106-119. (in French)

- Geneviève Xhayet, Partisans and adversaries of Louis of Anjou during the war of the Union of Aix Archived July 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Provence historique, Fédération historique de Provence, volume 40, No. 162, "Author of the War of the Union of Aix", 1990, p. 422. (in French)

- Under the direction of Edward Baratier, Georges Duby, and Ernest Hildesheimer, Historical Atlas. Provence, Venaissin County, Principality of Orange, County of Nice, Principality of Monaco, Paris, Librairie Armand Colin, 1969, p. 161 (Astoin), p. 164, p. 174 (Esparron), p. 192 (Reynier) BNF FRBNF35450017h (in French)

- Édouard Baratier, Provençal Demography from the 13th to the 16th centuries, with key comparisons with the 18th century, Paris, SEVPEN/EHESS, 1961, Démography and society collection, p. 70. (in French)

- Jean-Marie Schio, Guillaume II Roger de Beaufort (in French)

- Édouard de Laplane, History of Sisteron, taken from the archives, Digne, 1845, T. I, p. 126. (in French)

- Ernest Nègre, General Toponymy of France, Librairie Droz, 1990, Vol II, 676 pages, p. 1189, ISBN 2-600-00133-6 (in French).

- Marc de Leeuw, "The ways of communication", in Nicole Michel d'Annoville, Marc de Leeuw (directors) (photogr Gerald Lucas, drawing Michel Crespin.), Roaming the High Lands of Medieval Provence, Le Caire: The Association highlands of Provence; Saint-Michel-l'Observatoire, 2008, 223 p., ISBN 978-2-952756-43-3, p. 58. (in French)

- Bayons, Aftoin, Efparron. and Reynier on the 1750 Cassini Map

- Bayons, Astoin', Esparron, and Reynier on the 1790 Cassini Map

- G. Gauvin, "The Great Fear in the Lower Alps", Annals of Basses-Alpes, Vol. XII, 1905-1906. (in French)

- Henri Joannet, Jean-Pierre Pinatel, "Arrests-condemnations", 1851-For Memory, Les Mées: Les Amis des Mées, 2001, p. 72. (in French)

- Jean-Christophe Labadie (director), The Scvhoolhouses, Digne-les-Bains, Departmental Archives of Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, 2013, ISBN 978-2-86-004-015-0, p. 9, 11, 16, 18. (in French)

- Hélène Vésian-Claude Gouron, The ways of Liberty from the passive resistance of Haute-Provence, p. 76, 77, and 79. (in French)

- André de Réparaz, Lands lost, Lands constant, Lands conquered: vines and olives in Haute-Provence 19th-21st centuries, Méditerranée, 109, 2007, p. 56 and 59. (in French)

- EHESS, Communal notice for Bayons on the Cssdsini database, consulted on 23 July 2009. (in French)

- art L. 2121-2 of the General Code of Collective Territories (in French).

- List of Mayors of France (in French)

- Sébastien Thébault and Thérèse Dumont, The Liberation, Basses-Alpes 39-45, published 31 March 2014, consulted on 3 April 2014 (in French)

- List of competent jurisdictions for Bayons, Ministry of Justice website (in French).

- Local Taxes in Bayons, taxes.com (in French).

- INSEE Employment 2012, (in French),

- INSEE Characteristics of Enterprises 2014 (in French)

- Ministry of Agriculture, lien "Technico-economic orientation of Farming", Agricultural censuses of 2010 and 2000 (in French)

- Lamb of Sistern, INAO

- List of AOCs and IGPs for Bayons, INAO website (in French).

- Patrick Cros, Canal de Provence: hydroelectricity in synergy, News of local public enterprises, published 3 May 2011, consulted on 2 July 2012. (in French)

- Departmental Observatory of Tourism, Atlas of Tourist Accommodation, 2015 p. 40 (in French)

- Raymond Collier, Haute-Provence monumental and artistic, Digne, Imprimerie Louis Jean,? 1986, 559 p., p. 270. (in French)

- Raymond Collier, Haute-Provence monumental and artistic, Digne, Imprimerie Louis Jean,? 1986, 559 p., p. 312. (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00080356 Church of Notre-Dame-de-Bethléem

- Raymond Collier, Haute-Provence monumental and artistic, Digne, Imprimerie Louis Jean,? 1986, 559 p., p. 88. (in French)

- Raymond Collier, Haute-Provence monumental and artistic, Digne, Imprimerie Louis Jean,? 1986, 559 p., p. 75. (in French)

- Jacques Morel, Guide to Abbeys and Priories: monasteries, priories, convents. Central east and South-east of France, Éditions aux Arts, Paris, 1999. ISBN 2-84010-034-7, p. 59.

- Raymond Collier, Haute-Provence monumental and artistic, Digne, Imprimerie Louis Jean,? 1986, 559 p., p. 158. (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002324 Cross (Crucifix) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002323 Chalice (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002322 Cross (Crucifix) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002321 Painting: Joseph of Léonissa) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002320 Main Altar) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002319 Painting: Assumption) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002317 Painting: Saints Jacques and Peter at the foot of the virgin) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002316 Enclosures in the 2 lateral chapels) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002315 Pulpit lateral chapels) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002314 2 Pews) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002313 Statue: Virgin and child) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002312 Painting: Virgin of pity) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04002311 Painting: Saint Blaise) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04000353 Painting: Adoration of the magi) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04000352 Retable: Adoration of the magi) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04000036 Bronze bell) (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM04000035 Baptismal font) (in French)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bayons. |