Battle of Saint-Denis (1678)

The Battle of Saint-Denis on 14 August 1678 was the last major action of the Franco-Dutch War, fought four days after France and the Dutch Republic signed the Treaty of Nijmegen on 10 August. The battle is generally viewed as inconclusive.

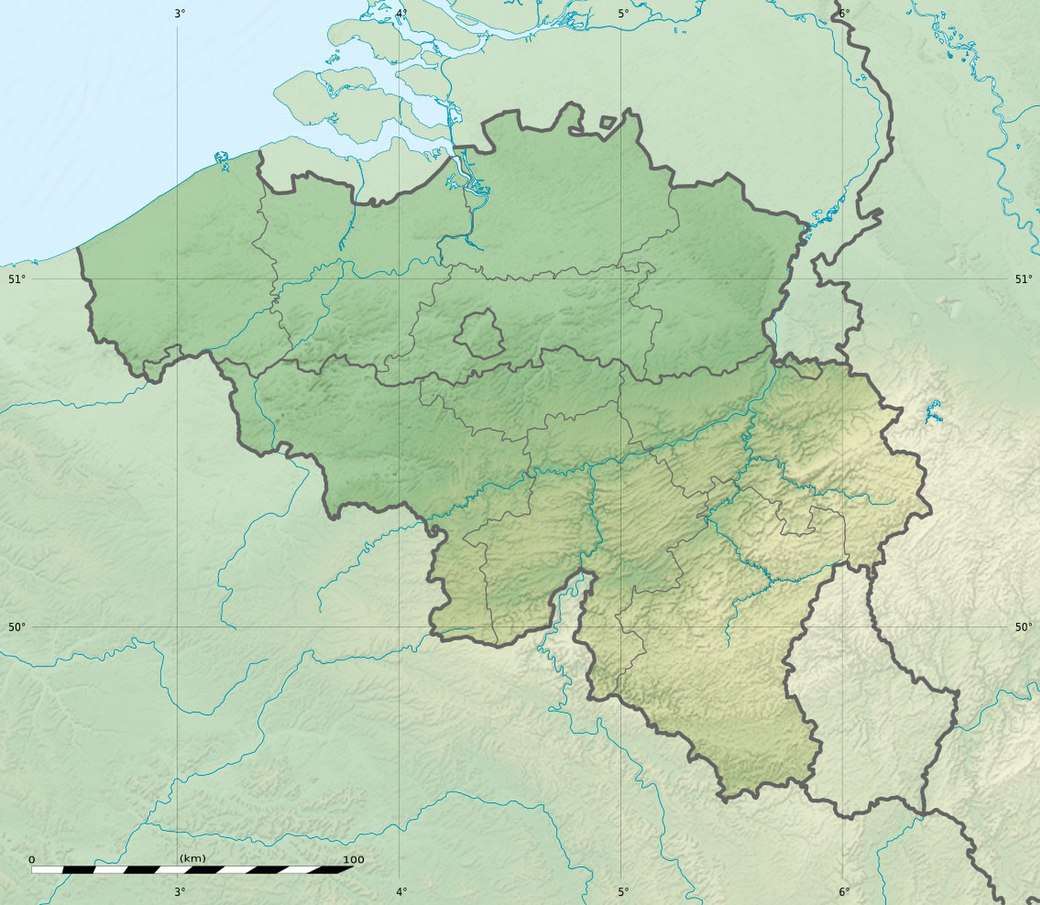

It took place around the villages of Saint-Denis and Casteau, just outside Mons, then in the Spanish Netherlands, now modern Belgium. A French army of 40,000 under Marshal Luxembourg was attacked by an Allied Dutch-Spanish army of 45,000 led by William of Orange.

The French successfully repulsed a series of assaults and after six hours of fighting, William ordered a retreat. The next morning however, Luxembourg abandoned the siege and his army withdrew back to France. William did not secure a victory on the field but his action had nonetheless achieved the allied objective of preventing the capture of Mons, which Spain retained in the treaty agreed with France on 17 September.

Background

In the 1667-1668 War of Devolution, France captured most of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté but relinquished most of these gains in the 1668 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle with the Triple Alliance of the Dutch Republic, England and Sweden. Before making another attempt, Louis XIV strengthened his diplomatic position by paying Sweden to remain neutral, while England agreed an alliance against the Dutch in the 1670 Treaty of Dover.[2]

In May 1672, French forces invaded the Dutch Republic and initially seemed to have achieved an overwhelming victory but by late July, the Dutch position had stabilised. Concern at French gains led to the August 1673 Treaty of the Hague between the Republic, Brandenburg-Prussia, Emperor Leopold and Charles II of Spain; in early 1674, Denmark joined the Alliance, while England and the Dutch made peace in the Treaty of Westminster.[3]

Forced into another war of attrition and with new fronts opening in Spain, Sicily and the Rhineland, French troops withdrew from the Dutch Republic by the end of 1673, retaining only Grave and Maastricht.[4] Louis now focused on recapturing Franche-Comté, which was completed by the end of June 1674 and French troops transferred to Condé's army in the Spanish Netherlands. The Battle of Seneffe on 11 August was a French victory but both sides suffered heavy losses and it confirmed Louis' preference for positional warfare, with siege and manoeuvre dominating in this theatre thereafter.[5]

The peace talks that began at Nijmegen in 1676 were given a greater sense of urgency in November 1677 when William of Orange married his cousin Mary, Charles II of England's niece. An Anglo-Dutch defensive alliance followed in March 1678, although English troops did not arrive in significant numbers until late May. This allowed Louis to improve his negotiating position by capturing Ypres and Ghent in early March, before signing a peace treaty with the Dutch on 10 August.[6]

Battle

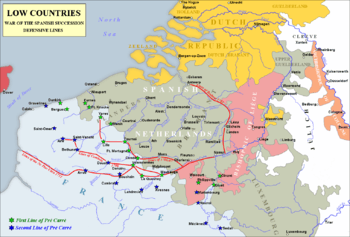

French strategy was driven by Vauban's pré carré plan, a double-line of fortresses to protect their northern borders (See Map). Mons was the most significant position still held by the Spanish; although the Dutch had agreed terms with France, Spain had not yet done so, and the delay provided an opportunity to capture it.[6]

During the March offensive that secured Ypres and Ghent, a French force under the Comte de Montal was based at Saint-Ghislain and Marville to blockade Mons. After England's entry into the war, Marshal Luxembourg was ordered to stay on the defensive but prevent any attempt to relieve it. On 12 August, his army of 40,000 was camped in the nearby villages of Saint-Denis and Casteau, with a Dutch and Spanish force of 45,000 based at Soignies, about three hours march away.[7]

William and Villahermosa were aware the Dutch were close to agreeing terms with France, but decided to attack anyway. The war with Spain continued regardless, and preventing the loss of Mons benefitted both the Spanish and Dutch.[8] Luxembourg, who was based in the Abbey de St Denis, an exposed position in front of the French right wing, reportedly learned of the Treaty on the morning of 14 August.[9]

Early in the afternoon, Villeroy reported the Allies were advancing on the abbey; assuming this to be a feint, Luxembourg ordered his artillery and baggage train to withdraw towards de Montal's positions at Saint-Ghislain. About 15:00, German mercenaries under Count Waldeck captured the Abbey, while Spanish and Dutch infantry, including the Anglo-Scots Brigade, attacked Villeroy's troops around Casteau. Concentrating on a narrow front allowed the Allies to take most of the village, but they failed to break Villeroy's front line.[10]

Once Luxembourg realised this was not a feint, he brought up his reserves; the battle for Casteau lasted over five hours, with church, mill and chateau changing hands several times. Both sides suffered heavy casualties in fierce hand-to-hand fighting; Luxembourg suffered minor wounds, while William was reportedly saved by future Marshal Hendrik Overkirk, who killed a French dragoon with his pistol against the Prince's chest.[11]

The Allies began to withdraw around 19:00, leaving troops in Casteau to cover their retreat, which then pulled back, with the exception of a regiment of French Huguenots exiles holding the chateau. Commanded by a former French regular officer, M de La Roque-Servière, they continued fighting until over-run just after 21:00, when the battle ended.[12]

French casualties were around 4,000 killed or wounded, including 689 in the elite Gardes Francaises, those of the Allies between 4,500 to 5,000.[13] The only British troops involved were the six regiments of the Anglo-Scots Brigade in Dutch service, commanded by the Earl of Ossory; while Monmouth was present and reportedly took part in a number of cavalry charges, the English Brigade which he commanded had not yet joined the main army.[14]

Aftermath

The French remained in possession of the battlefield, but the Allies achieved their strategic objective of ensuring Mons remained in Spanish hands. As a result, the battle is generally viewed as a draw, or inconclusive.[15]

Spain and France agreed an armistice on 19 August, with a formal peace treaty signed on 17 September. France returned Charleroi, Ghent and other towns in the Spanish Netherlands, but Spain ceded Ypres, Maubeuge, Câteau-Cambrésis, Valenciennes, Saint-Omer and Cassel; with the exception of Ypres, all of these remain part of modern France.[16]

References

- Dupuy 1986, p. 566.

- Lynn 1996, pp. 109-110.

- Davenport 1917, p. 238.

- Lynn 1996, p. 117.

- Lynn 1996, p. 125.

- Lesaffer.

- De Périni 1896, pp. 224–225.

- Lynn 1999, p. 152.

- De Périni 1896, p. 227.

- De Périni 1896, pp. 228-229.

- Frey & Frey 1995, p. 306.

- De Périni 1896, pp. 230-232.

- De Périni 1896, pp. 234-235.

- Ede-Borrett 2003, pp. 278–281.

- Sandler 2002, p. 514.

- Nolan 2008, p. 128.

Sources

- Davenport, Frances (1917). European Treaties bearing on the History of the United States and its Dependencies. Washington, D.C. Carnegie Institution of Washington.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises, Volume V. Ernest Flammarion, Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Ede-Borrett, Stephen (2003). "Casualties in the Anglo-Dutch Brigade at the battle of St Denis August 1678". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 81 (327). JSTOR 44230964.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Dupuy, Richard Ernest (1986). The Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the Present. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-181235-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Frey, Linda; Frey, Marsha (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313278846.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Lesaffer, Randall. "The Wars of Louis XIV in Treaties (Part V): The Peace of Nijmegen (1678–1679)". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 30 December 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Nolan, Cathal J (2008). Wars of the age of Louis XIV, 1650–1715. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-313-33046-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sandler, Stanley (2002). Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopedia. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-344-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Nimwegen, Olaf van (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588-1688 Volume 31 of Warfare in history, ISSN 1358-779X. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843835752.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);