Battle of Entzheim

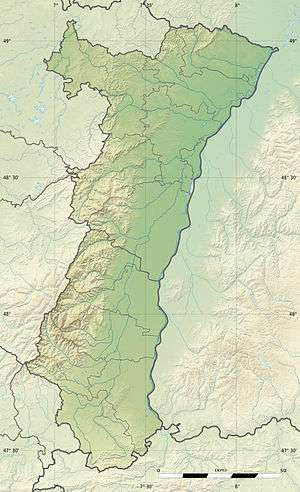

The Battle of Entzheim, also called Enzheim, or Ensheim, took place on 4 October 1674, during the 1672 to 1678 Franco-Dutch War. It was fought near the town of Entzheim, south of Strasbourg in Alsace, between a French army under Turenne, and an Imperial force commanded by Alexander von Bournonville.

| Battle of Entzheim | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Franco-Dutch War | |||||||

Battle of Enzheim (Martinet ill.; E. Ruhierre graveur.) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

22,000 men 30 guns |

35,000 men 50 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,500, killed, wounded and missing | 3,000–4,000 killed, wounded and missing [1] | ||||||

In this campaign, Turenne was able to compensate for being outnumbered by his aggression, which kept his opponents off-balance, and vastly superior logistics, which allowed him to move fast. Despite a strong defensive position and vastly superior numbers, Bournonville decided to retreat after a series of French assaults.

Although Turenne lost the same number of men as Bournonville, and a much higher proportion of his total force, it is generally considered a French strategic victory, since he prevented the Imperial army invading Eastern France. He also established a psychological advantage, setting the scene for the subsequent Winter Campaign.

Background

Both France and the Dutch Republic viewed the Spanish Netherlands as essential for their security and trade, making it a contested area throughout the 17th century. France occupied much of it in the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution, before returning it to Spain in the 1668 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.[2] After this, Louis XIV decided the best way to force concessions from the Dutch was by defeating them first.[3]

When the Franco-Dutch War began in May 1672, French troops quickly over-ran much of the Netherlands, but by July, the Dutch position had stabilised. The unexpected success of this offensive encouraged Louis to make excessive demands, while concern at French gains brought the Dutch support from Brandenburg-Prussia, the Emperor Leopold, and Charles II of Spain. In August 1673, an Imperial army entered the Rhineland; facing war on multiple fronts, the French relinquished most of their earlier gains.[4]

In January 1674, Denmark joined the anti-French coalition, followed by the February Treaty of Westminster, which ended the Third Anglo-Dutch War.[5] The allies agreed to focus on expelling France from its remaining positions in the Netherlands, while an Imperial army opened a second front in Alsace.[6] Turenne, French commander in Alsace, was ordered to prevent them breaking into Eastern France, or linking up with the Dutch. Known for his aggressive tactics, in 1673 he won a series of victories over Bournonville and Raimondo Montecuccoli, the only commander contemporaries considered his equal.[7]

In August 1674, the French defeated a combined Dutch-Imperial army at Seneffe; while this relieved pressure on their northern border, losses were so heavy they shocked the court.[8] In early September, an army of 40,000 under Bournonville crossed the Rhine at Strasbourg into Alsace, with another 20,000 led by Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg marching to join him. Once they combined, Turenne would be overwhelmed.[9]

Since Turenne could not expect reinforcements, the longer he delayed, the worse his position became, and he decided to take the offensive. French armies of the period held significant advantages over their opponents; undivided command, talented generals, and vastly superior logistics. Reforms introduced by Louvois, the Secretary of War, meant they could mobilise much more quickly than their adversaries, and campaign for longer.[10]

This flexibility allowed Turenne to attack his opponents individually, and at Sinsheim on 16 June, he inflicted heavy casualties on a detachment under Aeneas de Caprara.[11] However, he was unable to prevent him linking up with Bournonville, and their combined army of 35,000 then moved to Entzheim, to await Frederick William. To prevent this, Turenne left Molsheim on the night of 2–3 October, crossed the Bruche River, and arrived at Entzheim early on the morning of 4 October. The speed of his movement took Bournonville by surprise, and cut him off from Strasbourg.[12]

The battle

Bournonville significantly outnumbered his opponent, with 35,000 men, half of which were cavalry, and 50 guns. Despite this, he decided to fight a defensive battle; Turenne had to attack immediately, or risk being caught between the Imperialists and Fredrick William, while rain and mist meant conditions favoured the defenders. Most of his infantry was in the centre, anchored on Entzheim, supported by cavalry under Charles of Lorraine. On the right, his troops were hidden from view by meadows and vineyards, leading into the Foret de Bruche. His left was protected by a ditch, running from the village to the 'Little Wood', slightly in front of his position (see Map).[13]

The cavalry was split evenly between the two wings; the right included the elite Imperial Cuirassiers under Caprara, with the German states units commanded by the Prince de Holstein-Ploen on the left. The 'Little Wood' was key to the Imperial position, since it had to be taken in order to attack Entzheim; aware of this, Holstein-Ploen placed eight guns and six battalions of infantry in the wood itself, with another eight in reserve immediately behind.[13]

Turenne formed his army into two lines, infantry in the centre, and cavalry on the wings, the right commanded by the Marquis de Vaubrun, the left by his nephew, Guy Aldonce de Durfort de Lorges. He stationed the grenadier companies of his infantry regiments in the gaps between his cavalry squadrons, a tactic copied from Gustavus Adolphus. His artillery was placed in front of the infantry, in four batteries of eight guns.[14]

The second line and reserve included four English regiments, known as the British Brigade, commanded by Irish Catholic George Hamilton; one of its regiments was led by John Churchill, later Duke of Marlborough.[15] Although England had left the war, they had been encouraged to remain in French service to ensure Charles II would still be paid for them, as agreed in the 1670 Secret Treaty of Dover with Louis.[16]

Around 10:00 am, the French attacked the Little Wood with eight battalions of infantry, and dragoons under Louis Francois de Boufflers, a future Marshall of France. After the first assault was repulsed, they tried again, supported by four battalions from the second line, including the one commanded by Churchill. Holstein-Ploen responded by sending reinforcements from the reserve behind the wood, while heavy rain and mud impeded the French artillery as it tried to move forward; after two hours of back and forth combat, the French pulled back with heavy losses.[17]

Of the two English units involved, one lost 11 of 22 officers, the other all its officers and over half their men; Churchill later criticised Turenne's deployment.[18] Rather than another frontal attack, Vaubrun's cavalry tried to move around the Little Wood and take the defenders in the rear, but were repulsed by Holstein-Ploen. Simultaneously, the heavily-armed cuirassiers over-ran the French left, and the battle hung in the balance; however, the wet ground blunted the Austrian charge, and they quickly lost formation, allowing de Lorges to rally his troops, and force them back to the starting line.[19]

Meanwhile, a third assault by the rest of Hamilton's British brigade, plus those of Puisieux and Réveillon, finally captured the Little Wood, threatening the Imperial left. After an unsuccessful attack by Vaubrun on the troops entrenched around Entzheim, Turenne ended the assaults, instead bombarding them with his artillery. By now, it was getting dark, and both sides were exhausted; having lost between 3,000 - 4,000 men, Bournonville ordered a retreat.[1] The French had been marching or fighting for 40 hours non-stop, and their losses were about the same; aware they were incapable of making another attack, Turenne withdrew, leaving a small force of cavalry behind so that he could claim victory.[20]

Aftermath

The Imperials entered winter quarters near Colmar, but Turenne did not pursue him; his own losses were around 3,500 men, many incurred by the British brigade, which was disbanded. He took his army north to Dettwiller between Saverne and Haguenau, where his exhausted troops could rest and refit.[19] Entzheim was a tactical draw, but a strategic French victory; despite superior numbers, Bournonville had been prevented from entering French-held territory.[21]

The losses suffered by the British Brigade at Entzheim, combined with restrictions imposed on recruiting by Parliament, reduced its numbers from a nominal 4,000 to less than 1,400. Churchill and other senior officers left for England, and in May 1675, Parliament ordered any men still in France to return home. Hamilton's regiment, primarily composed of Irish Catholics like himself, remained in French service throughout the war; one of his officers was Patrick Sarsfield, senior Irish commander during the Williamite War in Ireland.[22]

The campaign that started in June 1674 and ended with his death in July 1675 has been described as 'Turenne's most brilliant campaign.' Significantly outnumbered, he used stealth and boldness to fight the Imperial army to a standstill at Entzheim; with his enemy now inactive, he was able to plan the winter movement that would culminate in decisive victory at the Battle of Turckheim.[23]

Entzheim still exists, but most of the battlefield now lies beneath Strasbourg International Airport.[24]

Notes and References

- Clodfelter 2008, p. 46.

- Macintosh 1973, p. 165.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 109-110.

- Lynn 1999, p. 125.

- Hutton 1989, p. 317.

- Chandler 1979, p. 40.

- Guthrie 2003, p. 239.

- De Sévigné 1822, p. 353.

- Macintosh 1973, p. 170.

- Black 2011, pp. 97–99.

- De Périni 1896, pp. 71-74.

- Rousset 1865, p. 86.

- Grimoard 1782, p. 129.

- De Périni 1896, p. 114.

- Holmes 2008, p. 80.

- Kenyon 1986, p. 83.

- De Périni 1896, p. 115.

- Holmes 2008, pp. 80–81.

- Lynn 1999, p. 132.

- De Périni 1896, p. 122.

- Tucker 2010, p. 651.

- Atkinson 1946, p. 162.

- Chandler 1979, pp. 63-64.

- Google (20 June 2020). "Strasbourg airport" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

Sources

- Atkinson, CT (1946). "Charles II's regiments in France, 1672 - 1678". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 24 (100). JSTOR 44228420.

- Black, Jeremy (2011). Beyond the Military Revolution: War in the Seventeenth Century World. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230251564.

- Chandler, David G (1979). Marlborough as Military Commander (2nd, illustrated ed.). Batsford. ISBN 978-0713420753.

- Clodfelter, Michael (2008). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1494-2007 (3rd ed.). McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-3319-3.

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises, Volume V. Ernest Flammarion.

- De Sévigné, Marie Rabutin-Chantal (1822). De St-Germain, Pierre Marie Gault (ed.). Letters of Madame De Sévigné, Volume III; to the Count de Bussy, 5 September 1674.

- Grimoard, Philippe-Henri, comte de (1782). Histoire Des Quatre Dernieres Campagnes Du Maréchal de Turenne en 1672, 1673, 1674, 1675. De Baurain. p. 129. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Guthrie, William P. (2003). The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia (Contributions in Military Studies). Praeger. ISBN 978-0313324086.

- Holmes, Richard (2008). Marlborough: Britain’s Greatest General: England's Fragile Genius. Harper Press. ISBN 978-0007225712.

- Hutton, Ronald (1989). Charles II King of England, Scotland and Ireland. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198229117.

- Kenyon, John Philipps (1986). The History Men: The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Lynn, John A. (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714. Addison Wesley Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- Macintosh, Claude Truman (1973). French Diplomacy during the War of Devolution, the Triple Alliance and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (PhD). Ohio State University.

- Rousset, Camille (1865). Histoire de Louvois et de son administration politique et militaire jusqu’à la paix de Nimègue (in French). 2. Paris: Didier & Cie.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict. Santa Barbara, California: ABC CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.