Charles de Montsaulnin, Comte de Montal

Charles de Montsaulnin, Comte de Montal (1619–1696) was a 17th-century French military officer and noble who served in the wars of Louis XIV.

Charles de Montsaulnin, Comte de Montal, Seigneur de Ménétreux-le-Pitois and Venarey-les-Laumes | |

|---|---|

The Chateau des Aubues, mid-19th century | |

| Born | 1619 (other sources claim 1621) Château des Aubues, near Lormes, Nièvre |

| Died | 21 September 1696 (aged 77) Dunkirk[1] |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Army |

| Years of service | 1638–1696 |

| Rank | Lieutenant-General 1676 |

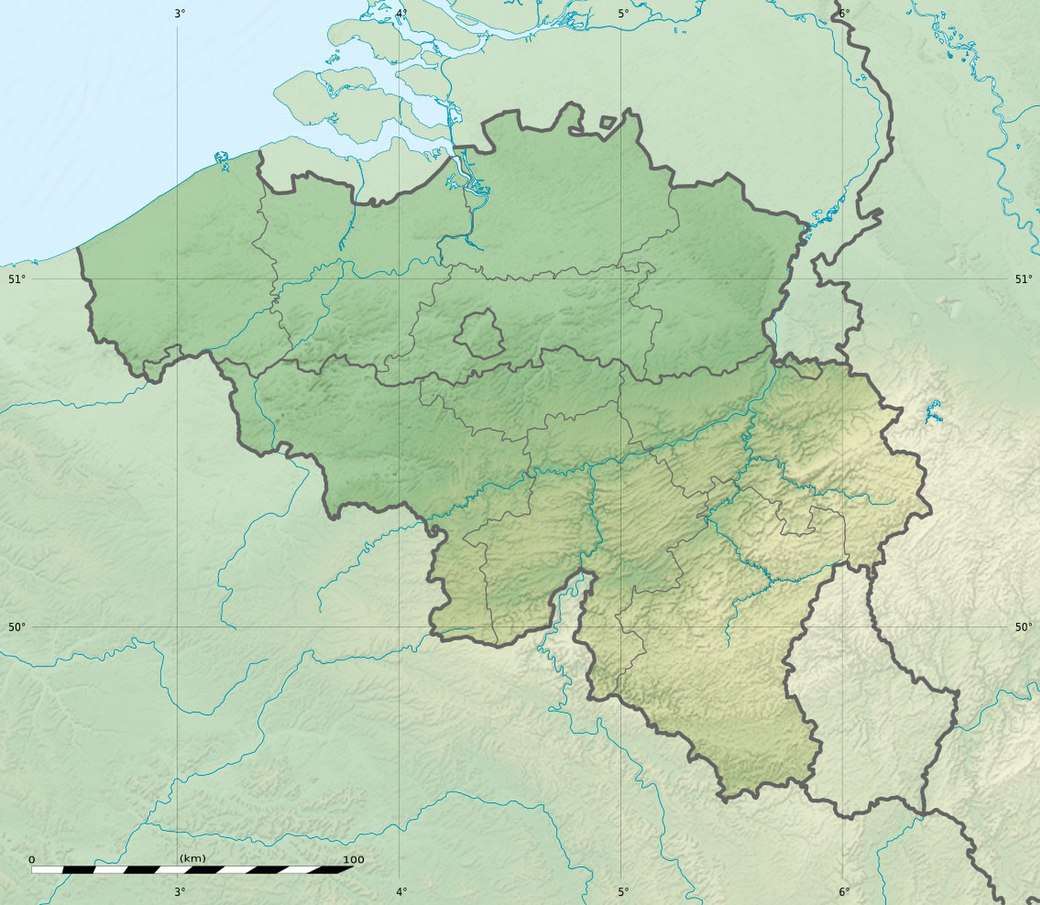

| Commands held | Charleroi 1667–1678 Maubeuge and Dinant 1678–1684, Mont-Royal 1687–1692 Maritime Flanders 1693–1696 |

| Battles/wars | Fronde 1648–1653 Franco-Spanish War, 1635–1659 Freiburg 1644 Nördlingen 1645 Valenciennes 1656 War of Devolution 1667–1668 War of the Reunions 1683–1684 Franco-Dutch War 1672–1678 Siege of Maastricht 1673 Seneffe 1674 Saint-Denis 1678 1689–1697 Nine Years' War Steenkerque 1692 Diksmuide 1695 |

| Awards | Order of the Holy Spirit 1688 |

Life

Charles de Montsaulnin was born in 1619 near Lormes in the French province of Nièvre, at the Château des Aubues; built by the Montsaulnin family in 1480, it was demolished in the late 19th century and little trace of it remains today.[2] He was the only surviving son of Adrien de Montsaulnin, Comte de Montal (ca 1590 to 1632) and Gabrielle de Routin, who also had two daughters; Claude (sic, died 1697) and Adrienne.[3]

In 1640, he married Gabrielle de Soultage (1634–?); they had four surviving children, three sons and a daughter. The eldest, Louis (1648–1686), joined his father's regiment in 1667, fought with him in Flanders and died of disease in Paris; his son, Charles-Louis de Montsaulnin (? – 1758) became de Montal's heir.[4]

Of their other children, François (1653–1672) was enrolled in the Knights of Malta religious order, fought at the Siege of Crete when only 15 and was killed in Flanders in 1672. François-Ignace (ca 1650–1691), known as the Abbé de Montal, began his career in the church but left it in 1680; he married and died in 1691 of wounds received while serving with the Regiment de Beaupré at Landau. Cassandre-Marie (? – 1695) married François-Eustache, Comte de Druy, whose family were neighbours in Nièvre.[5]

Career

The first half of the 17th century in France was a period of intense civil strife; the 1590 Edict of Nantes ended the French Wars of Religion but a series of Huguenot rebellions broke out in the 1620s. French support for the Protestant Dutch Republic in its rebellion against Catholic Spain led to the 1635–1659 Franco-Spanish War, accompanied by a 1648–1653 civil war known as the Fronde.

De Montal began his military career in 1638 as a captain in the regiment of the duc d'Enghien, later the Grand Condé, the leading French general of the period. He took part in the 1639 capture of the Spanish border fortress of Salses-le-Château, but the French were forced to retreat in 1640 after Condé's army disintegrated.[6] He then joined Turenne during his Rhineland campaign of 1644–1646, fighting at the battles of Freiburg and Nördlingen.[7]

When the so-called Fronde des nobles began in 1650, both Turenne and Condé opposed the Court party led by Louis XIV's mother, Anne of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin. Turenne switched sides in 1651 and the Battle of the Faubourg St Antoine in July 1652 ended the Fronde as a serious military threat; de Montal was one of the few to follow Condé when he fought on with the Spanish.[8]

In 1648, Louis XIII had granted the county of Clermont-en-Argonne to Condé, who established Sainte-Menehould as the capital; he fortified it in 1652, with De Montal as garrison commander. A young Vauban worked on the fortifications; he came from the same district in Nievre as de Montal and the two were colleagues for many years, although Vauban changed sides when captured by a Royalist patrol in early 1653.[9]

De Montal surrendered the town in November 1653, allegedly in return for a payment of 50,000 pistoles.[10] However, he was appointed Spanish governor of Rocroi and fought in the 1656 Battle of Valenciennes, a crushing defeat inflicted by Condé on his French countrymen.[11]

The 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees ending the war with Spain included an agreement that de Montal and Condé be allowed to return home, although it was not until the 1667-1668 War of Devolution that either of them was trusted with a military command again. De Montal served in Condé's army that over-ran Franche-Comté in 1668 but the province was returned to Spain in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

The French retained the strategic town of Charleroi in the Spanish Netherlands; its fortifications were upgraded by Vauban and de Montal appointed Governor, a position he retained until 1678. During the 1672–1678 Franco-Dutch War, he commanded part of the assault force that stormed Maastricht in June 1673.[12] He later repulsed an attempt by William of Orange to take Charleroi in 1673 and was wounded at Seneffe in 1674. During the winter of 1676/1677, he supported a tight French blockade of the Spanish-held towns of Valenciennes and Cambrai by seizing any grain being transported from Namur and preventing reinforcements reaching either garrison.[13]

Active campaigning in Flanders largely ended after the two towns surrendered in spring 1677 but de Montal was involved in the last action of the war, the Battle of Saint-Denis in August 1678. In return for his service, he was appointed Governor of the newly-acquired towns of Dinant and Maubeuge, when Charleroi was returned to Spain in the 1678 Treaty of Nijmegen.[14]

The 1683–1684 War of the Reunions was short but relatively brutal, since Louvois, French Minister of War, sought to pressure the local populace into suing for peace by destroying crops and buildings. As Governor of Maubeuge, de Montal was ordered to burn 20 villages around Charleroi in retaliation for Spanish raids into France.[15]

Louis XIV reportedly remarked sieges should ideally be conducted by Vauban and defended by de Montal, but could only happen once, since they would kill each other.[16] His confidence in their abilities was demonstrated in 1687 when Vauban was ordered to construct a new fortress called Mont-Royal, with de Montal as Governor. Located on the Moselle, near Traben-Trarbach in modern Germany, Mont-Royal was an advanced position that provided a vital stepping-off point for French offensives into the Rhineland.[17] Built 200 metres above the Moselle, with main walls 30 metres high and three kilometres long, it had space for 12,000 troops but was demolished when the French withdrew following the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick.[18]

Despite his age, de Montal held a number of commands in Flanders during the 1688–1697 Nine Years War and was instrumental in rallying the French infantry when they were taken by surprise at Steenkerque in 1692.[19] However, although promoted Lieutenant-General in 1676, he never became a Marshall of France; it is suggested this was due to his defence of Sainte-Menehould in 1653, a siege conducted by Louis XIV himself.[20] The title was largely ceremonial but de Montal complained about his exclusion from the list of promotions in 1693 and Louis appointed him commander of French forces in Maritime Flanders, based at Dunkirk.[21]

By this stage of the war, Maritime Flanders was a quiet sector and one of his last actions was the capture of Diksmuide in 1695. He died at Dunkirk on 19 September 1696 and was buried at Saint-Brisson in the family vault, which was later destroyed in the French Revolution.

Legacy

The 'Rue Montal' in Charleroi was named after him by the city council in 1860, commemorating his period as governor from 1667–1678.[22]

His sister Adrienne married Edmé Renaud d'Avesnes des Méloizes and in 1685, their son François-Marie (ca 1655–1699) was posted to New France in command of the Troupes de Marine; Frontenac considered him "one of the best and wisest officers" in Canada.[23] He married Françoise-Thérèse (1670–1698), daughter of Nicholas Dupont de Neuville (1632–1716), a member of the Sovereign Council of New France and is buried in Notre-Dame Basilica-Cathedral in Quebec.

References

- Marchi, François. "Charles de Montsaulnin, Comte de Montal (1619–1696)". Genealogie Quebec. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Chateau des Aubues". Patrimoine du Morvan. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Adrien de Montsaulin".

- Moreri, Louis (1749). Le grand dictionnaire historique ou Le melange curieux de l'Histoire sacrée; Volume I. Libraires Associes, Paris. p. 690. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- De Blancourt, Haudicquer (1710). Recherches historiques de l'Ordre du S. Esprit, Volume 2. Claude Jombert, Paris. pp. 368–370. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Parrot, David (2008). Richelieu's Army: War, Government and Society in France, 1624–1642. Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-0521025485.

- "Famille De Montsaulnin". Menetreux-le-pitois. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Tucker, Spencer C (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East 6V: A Global Chronology of Conflict [6 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 654. ISBN 978-1851096671.

- Duffy, Christopher (1995). Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World 1494–1660. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0415146494.

- Birch, Thomas (1742). A Collection of the State Papers of John Thurloe. Thomas Woodward, Paternoster Row. p. 595. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Black, Jeremy (2009). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution; Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0521470339.

- Childs, John (2014). General Percy Kirke and the Later Stuart Army (2015 ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. p. 217. ISBN 978-1474255141.

- Satterfield, George (2003). Princes, Posts and Partisans: The Army of Louis XIV and Partisan Warfare in the Netherlands (1673–1678). Brill. pp. 298–299. ISBN 978-9004131767.

- "Treaty of Peace between France and Spain, signed at Nimeguen, 17 September 1678" (PDF). Oxford International Public Law. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Lynne, John Albert (1993). "How War Fed War: The Tax of Violence and Contributions during the Grand Siècle". The Journal of Modern History. The University of Chicago Press. 65 (2): 301. doi:10.1086/244639.

- Moreri p 690

- Duffy p. 20

- "Fortress Mont Royal". Traben-Tarbach Tourist Information. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Moreri p 690

- Moreri p 690

- De Courcillon, Phillipe (1825). Memoirs of the Court of France; 1684–1720. Henry Colman. p. 280.

- Everard, Jean (1959). Monographie des rues de Charleroi. Collins. p. 223.

- La prévôté de Québec, registre de 1695, 25 novembre, 128–130. Correspondance de Frontenac (1689–99)

Sources

- Birch, Thomas (1742). A Collection of the State Papers of John Thurloe. Thomas Woodward, Paternoster Row.;

- Black, Jeremy (2009). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution; Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521470339.;

- Childs, John (2014). General Percy Kirke and the Later Stuart Army. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1474255141.;

- De Blancourt, Haudicquer (1710). Recherches historiques de l'Ordre du S. Esprit, Volume 2. Claude Jombert, Paris. pp. 368–370.;

- De Courcillon, Phillipe (1825). Memoirs of the Court of France; 1684–1720. Henry Colman.;

- Duffy, Christopher (1995). Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World 1494–1660. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415146494.;

- Everard, Jean (1959). Monographie des rues de Charleroi. Collins.;

- Lynn, John (1993). "How War Fed War: The Tax of Violence and Contributions during the Grand Siècle". The Journal of Modern History. The University of Chicago Press. 65 (2): 301.;

- Moreri, Louis (1749). Le grand dictionnaire historique ou Le melange curieux de l'Histoire sacrée; Volume I. Libraires Associes, Paris. p. 690.

- Parrot, David (2008). Richelieu's Army: War, Government and Society in France, 1624–1642. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521025485.;

- Satterfield, George (2003). Princes, Posts and Partisans: The Army of Louis XIV and Partisan Warfare in the Netherlands (1673–1678). Brill. ISBN 978-9004131767.;

- Tucker, Spencer C (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East 6V: A Global Chronology of Conflict [6 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851096671.;

External links

- "Fortress Mont Royal". Traben-Tarbach Tourist Information.;

- "Treaty of Peace between France and Spain, signed at Nimeguen, 17 September 1678" (PDF). Oxford International Public Law. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.;

- "Famille De Montsaulnin". Menetreux-le-pitois.;

- "Adrien de Montsaulin".;

- "Chateau des Aubues". Patrimoine du Morvan.;

| French nobility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Adrien de Montsaulnin |

Comte de Montal 1632–1696 |

Succeeded by Charles-Louis de Montsaulnin |