Bandelier National Monument

Bandelier National Monument is a 33,677-acre (13,629 ha) United States National Monument near Los Alamos in Sandoval and Los Alamos counties, New Mexico. The monument preserves the homes and territory of the Ancestral Puebloans of a later era in the Southwest. Most of the pueblo structures date to two eras, dating between 1150 and 1600 AD.

| Bandelier National Monument | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

Reconstructed kiva at Alcove House | |

| |

| Location | Sandoval, Los Alamos and Santa Fe counties, New Mexico, United States |

| Nearest town | Los Alamos, New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 35°46′44″N 106°19′16″W[1] |

| Area | 33,677 acres (136.29 km2)[3] |

| Created | February 11, 1916 |

| Visitors | 200,741 (in 2019)[4] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Bandelier National Monument |

Bandelier National Monument | |

| Built | 1200 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000042[5] (original) 14001017[6] (increase) |

| NMSRCP No. | 56 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Boundary increase | December 10, 2014 |

| Designated NMSRCP | May 21, 1971 |

The monument is 50 square miles (130 km2) of the Pajarito Plateau, on the slopes of the Jemez volcanic field in the Jemez Mountains. Over 70% of the monument is wilderness, with over one mile of elevation change, from about 5,000 feet (1,500 m) along the Rio Grande to over 10,000 feet (3,000 m) at the peak of Cerro Grande on the rim of the Valles Caldera, providing for a wide range of life zones and wildlife habitats. Three miles of road and more than 70 miles of hiking trails are built. The monument protects Ancestral Pueblo archeological sites, a diverse and scenic landscape, and the country's largest National Park Service Civilian Conservation Corps National Landmark District.

Bandelier was designated by President Woodrow Wilson as a national monument on February 11, 1916, and named for Adolph Bandelier, a Swiss-American anthropologist, who researched the cultures of the area and supported preservation of the sites. The park infrastructure was developed in the 1930s by crews of the Civilian Conservation Corps and is a National Historic Landmark for its well-preserved architecture. The National Park Service cooperates with surrounding Pueblos, other federal agencies, and state agencies to manage the park.

Geography and geology

In October 1976, roughly 70% of the monument, 23,267 acres (9,416 ha), was included within the National Wilderness Preservation System.[7] The park's elevations range from about 5,000 feet (1,500 m) at the Rio Grande to over 10,200 feet (3,100 m) at the summit of Cerro Grande.[8] The Valles Caldera National Preserve adjoins the monument on the north and west, extending into the Jemez Mountains.

Much of the area was covered with volcanic ash (the Bandelier tuff) from an eruption of the Valles Caldera volcano 1.14 million years ago. The tuff overlays shales and sandstones deposited during the Permian Period and limestone of Pennsylvanian age. The volcanic outflow varied in hardness; the Ancestral Puebloans broke up the firmer materials to use as bricks, while they carved out dwellings from the softer material.[9]

History

Human presence in the area has been dated to over 10,000 years before present. Permanent settlements by ancestors of the Puebloan peoples have been dated to 1150 CE; these settlers had moved closer to the Rio Grande by 1550.[10] The distribution of basalt and obsidian artifacts from the area, along with other traded goods, rock markings, and construction techniques, indicate that its inhabitants were part of a regional trade network that included what is now Mexico.[11] Spanish colonial settlers arrived in the 18th century. The Pueblo Jose Montoya brought Adolph Bandelier to visit the area in 1880. Looking over the cliff dwellings, Bandelier said, "It is the grandest thing I ever saw."[12]

Based on documentation and research by Bandelier, support began for preserving the area and President Woodrow Wilson signed the legislation creating the monument in 1916. Supporting infrastructure, including a lodge, was built during the 1920s and 1930s. The structures at the monument built during the Great Depression by the Civilian Conservation Corps constitute the largest assembly of CCC-built structures in a national park area that has not been altered by new structures in the district. This group of 31 buildings illustrates the guiding principles of National Park Service Rustic architecture, being based on local materials and styles. It has been designated as a national landmark district.

During World War II, the monument area was closed to the public for several years, since the lodge was being used to house personnel working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos to develop an atom bomb.[13] In 2019, Senator Martin Heinrich (D-NM), announced plans to introduce legislation to redesignate Bandelier National Monument as a national park and preserve.[14]

Monument description

Frijoles Canyon contains a number of ancestral pueblo homes, kivas (ceremonial structures), rock paintings, and petroglyphs. Some of the dwellings were rock structures built on the canyon floor; others were cavates produced by voids in the volcanic tuff of the canyon wall and carved out further by humans. A 1.2-mile (1.6 km), predominantly paved, "Main Loop Trail" from the visitor center affords access to these features. A trail extending beyond this loop leads to Alcove House (formerly called Ceremonial Cave, and still so identified on some maps), a shelter cave produced by erosion of the soft rock and containing a small, reconstructed kiva that hikers may enter via ladder.

Ancient pueblo sites

One site of archaeological interest in the canyon is Tyuonyi (Que-weh-nee) pueblo and nearby building sites, such as Long House. Tyuonyi is a circular pueblo site that once stood one to three stories tall. Long House is adjacent to Tyounyi, built along and supported by the walls of the canyon. A reconstructed Talus House is also found along the Main Loop Trail.

These sites date from the Pueblo III Era (1150 to 1350) to the Pueblo IV Era (1350 to 1600). The age of the Tyuonyi construction has been fairly well established by the tree-ring method of dating, widely and successfully used by archeologists in the Southwest. Ceiling-beam fragments recovered from various rooms have been dated between 1383 and 1466. This general period seems to have been a time of much building in Frijoles Canyon; a score of tree-ring dates from the Rainbow House ruin, which is down the canyon a half-mile, also fall in the early and middle 15th century. Perhaps the last construction anywhere in Frijoles Canyon occurred close to 1500, with a peak of population reached near that time or shortly thereafter.

The century before Tyuonyi's construction is thought to have been characterized by intense change and migration in the Ancestral Puebloan culture. The period of highest population density in Frijoles Canyon corresponds to a period contemporaneous with a wide-scale migration of Ancestral Puebloans away from the Four Corners area, which was suffering a deep drought, environmental stress, and social unrest in the Pueblo III period. Scholars believe that some Ancestral Puebloan groups relocated into the Rio Grande valley, southeast of their former territories, founding Tyuonyi and nearby sites. The pueblo was abandoned by 1600. The inhabitants relocated to pueblos near the Rio Grande, such as Cochiti and San Ildefonso Pueblos, which have been occupied ever since.

Other, more rustic trails enter the backcountry, which contains additional smaller archaeological sites, canyon/mesa country, and some transient waterfalls. Hikes to many of these areas are feasible and range in length from short (<1 hour) excursions to multi-day backpacks. Some of the backcountry sites have been submerged, damaged, or rendered inaccessible by Cochiti Lake, a reservoir on the Rio Grande created to reduce the seasonal flooding that threatened communities and agricultural areas downstream.

A detached portion of the monument, called the Tsankawi unit, is located near the town of Los Alamos. It has some excavated sites and petroglyphs. Also at the Tsankawi unit are the remains of the home and school for indigenous people established in the late 19th century by Baroness Vera von Blumenthal and her lover Rose Dougan (or Dugan).

In the upper elevations of the monument, Nordic skiing is possible on a small network of trails reachable from New Mexico Highway 4. Not every winter produces snowfall sufficient to allow good skiing.

Wildlife at Bandelier

Wildlife is locally abundant, and deer and Abert's squirrels are frequently encountered in Frijoles Canyon. Black bear and mountain lions inhabit the monument and may be encountered by the backcountry hiker. A substantial herd of elk are present during the winter months, when snowpack forces them down from their summer range in the Jemez Mountains.

Notable among the smaller mammals of the monument are large numbers of bats that seasonally inhabit shelter caves in the canyon walls, sometimes including those of Frijoles Canyon near the loop trail. Wild turkeys, vultures, ravens, several species of birds of prey, and a number of hummingbird species are common. Rattlesnakes, tarantulas, and "horny toads" (a species of lizard) are occasionally seen along the trails.

Bandelier Museum

The visitor center at Bandelier National Monument features exhibits about the site's inhabitants, including Ancestral Pueblo pottery, tools and artifacts of daily life. Two life-size dioramas demonstrate Pueblo life in the past and today. Also featured are contemporary Pueblo pottery pieces, 14 pastel artworks by Works Progress Administration artist Helmut Naumer Sr, and wood furniture and tinwork pieces created by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Depression. A 10-minute introductory film provides an overview of the monument.

Trails

The National Park service has noted several designated trails, advising visitors to bring adequate safe water supplies on some trails.

The Main Loop Trail is 1.2 miles (1.9 km) long and loops through archeological areas, including the Big Kiva, Tyuonyi, Talus House, and Long House. It will take between 45 minutes and one hour. There are some optional ladders to allow access to the cavates (small human-carved alcoves).[15]

Prior to the construction of the modern entrance road, the Frey Trail was the only access to the canyon. Originally, the parking lot was at the canyon rim. Today, the trail starts at the campground amphitheater. The trail is 1.5 miles (2.4 km) one way. There is an elevation change of 550 feet (170 m).[16]

The Alcove House trail begins at the west end of the Main Loop trail and extends 0.5 miles (0.80 km) to Alcove House. Previously called the Ceremonial Cave, the alcove is located 140 feet (43 m) above the floor of Frijoles Canyon. This pueblo was the home of around 25 Ancestral Pueblo people. Except in winter, the site is reached by four wooden ladders and stone stairs. Alcove House has a reconstructed kiva that offers views of viga holes and niches of several homes.[17]

As of spring 2013, however, access to the kiva's interior is closed indefinitely for safety reasons associated with stabilization of the structure. Ladders and stairs have been reopened to public use.

The Falls Trail starts at the east end of the Backpacker's Parking Lot. Over its 2.5 miles (4.0 km), it descends 700 feet (210 m), passing two waterfalls and ending at the Rio Grande. But, trail damage resulting from the 2011 Las Conchas Fire has led to the indefinite, and possibly permanent, closure of the trail beyond Upper Frijoles Falls, pending remediation. In addition to the elevation change, the trail's challenges include steep dropoffs at many places along the trail and a lack of bridges over Frijoles Creek. These continue to factors on the portion of the trail that is open.[18]

The 2.5 miles (4.0 km) Frijolito Loop Trail is more strenuous. It starts in the Cottonwood Picnic Area and climbs out of Frijoles Canyon using a switchback path. Once on top of the mesa, it passes Frijolito Pueblo. It returns to the visitor center along the Long Trail.[19]

Gallery

- Bandelier

Main cliff on loop trail

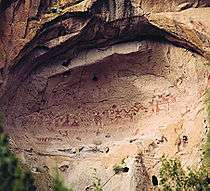

Main cliff on loop trail Painted Cave, Ancestral Puebloan pictographs in the Bandelier backcountry

Painted Cave, Ancestral Puebloan pictographs in the Bandelier backcountry Forested mesa tops are framed by the San Miguel Mountains in the Bandelier Wilderness

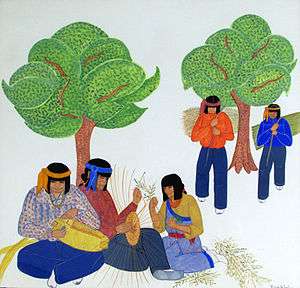

Forested mesa tops are framed by the San Miguel Mountains in the Bandelier Wilderness Basketmaking by Pablita Velarde, c.1940. Bandelier museum collection

Basketmaking by Pablita Velarde, c.1940. Bandelier museum collection Park headquarters

Park headquarters Tyuonyi Pueblo, Detail

Tyuonyi Pueblo, Detail Tent-Rocks

Tent-Rocks Cliff Dwellings detail, showing stone and wood use, Bandelier National Monument, NM

Cliff Dwellings detail, showing stone and wood use, Bandelier National Monument, NM Cliff Dwelling detail, Bandelier National Monument, NM

Cliff Dwelling detail, Bandelier National Monument, NM

National Park Service Rustic style

Bandelier CCC Historic District | |

.jpg) Superintendent's Residence, Bandelier CCC Historic District, in 1984 | |

| Area | 54 acres (22 ha) |

|---|---|

| Built | 1933 |

| Architect | Lyle Bennett; Et al. |

| Architectural style | Pueblo Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 87001452[5] |

| NMSRCP No. | 56 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 28, 1987 |

| Designated NHLD | May 28, 1987[20] |

| Designated NMSRCP | May 21, 1971 |

Bandelier has excellent examples of CCC-constructed National Park Service Rustic style of architecture, built during the Great Depression by work crews while the area was managed by the U.S. Forest Service. The Bandelier CCC camp employed several thousand men from 1933 to 1941 as a New Deal works project, and built roads, trails, and park buildings and other amenities. In 1943, camp provided temporary housing for scientists, technicians, and their families involved in the secret Manhattan Project at nearby Los Alamos. Construction contractors were housed there in early 1944.[21]

The park's service area was designed to resemble a traditional Pueblo village. Most of the CCC-built buildings are set around a wooded plaza at the end of the main access road (also a CCC construction), and were designed to house the monument staff, provide accommodations and services for visitors, and included maintenance areas. These historic structures include the Frey Lodge (park headquarters); the guest cabins (employee housing), the gift shop, and the park visitor center. The CCC crews also built furniture for these facilities, and artists paid by the Federal Arts Project provided artwork. The preserved elements of the CCC construction were designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987.[22][21][20][23]

See also

References

- "Bandelier National Monument". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- "Bandelier National Monument". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- "Annual Visitation Report by Years: 2009 to 2019". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 12/08/14 through 12/12/14". National Park Service. December 19, 2014. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Bandelier Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- "Bandelier National Monument – Nature & Science". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- "Bsndelier Tuff – Valles Caldera". Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- Bandelier National Monument: History and Culture], National Park Service

- "Main Loop Trail Stop 18". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- Warner, Edith; Burns, Patrick (2008). In the shadow of Los Alamos. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8263-1978-4.

- "History & Culture". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- https://www.abqjournal.com/1294260/heinrich-bill-would-make-bandelier-a-national-park.html

- "Main Loop Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- "Frey Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- "Alcove House". National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- "Falls Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- "Frijolito Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- "National Historic Landmarks Survey, New Mexico" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Laura Soullière Harrison (1985). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Bandelier Buildings and Frijoles Canyon Lodge / Bandelier National Monument CCC Historic District (preferred)" (pdf). National Park Service. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) and Accompanying 29 photos, from 1984 (32 KB) - "Bandelier CCC Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ""Architecture in the Parks: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study: Bandelier National Monument CCC Historic District", by Laura Soullière Harrison". National Historic Landmark Theme Study. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

Further reading

- Hoard, Dorothy (1995). A Guide to Bandelier National Monument. Los Alamos Historical Society. ISBN 0-941232-09-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bandelier National Monument. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bandelier National Monument. |