Baniyas

Baniyas (Arabic: بانياس Bāniyās) is a city in Tartous Governorate, northwestern Syria, located 55 km (34 mi) south of Latakia (ancient Laodicea) and 35 km (22 mi) north of Tartous (ancient Tortosa).

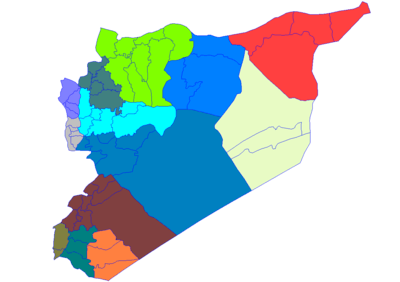

Baniyas بانياس | |

|---|---|

| |

Baniyas Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 35°10′56″N 35°56′25″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Latakia |

| District | Baniyas |

| Subdistrict | Baniyas |

| Elevation | 25 m (82 ft) |

| Population (2009 est.) | |

| • Total | 43,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 |

| Area code(s) | 43 |

| Geocode | C5360 |

It is known for its citrus fruit orchards and its export of wood. North of the city is an oil refinery, one of the largest in Syria, and a power station. The oil refinery is connected with Iraq with Kirkuk–Baniyas pipeline (now defunct).

On a nearby hill stands the Crusader castle of Margat (Qalaat el-Marqab), a huge Knights Hospitaller fortress built with black basalt stone.

History

In Phoenician and Hellenistic times, it was an important seaport. Some have identified it with the Hellenistic city of Leucas (from colonists from the island Lefkada), in Greece, mentioned by Stephanus of Byzantium. It was a colony of Aradus[1], and was placed by Stephanus in the late Roman province of Phoenicia, though it belonged rather to the province of Syria.[2] In Greek and Latin, it is known as Balanaea or Balanea.

During the early 21st century Syrian civil war, rebel sources reported that a massacre took place on 2 May 2013, perpetrated by regime forces.[3] On 3 May,[4] another massacre was, according to SOHR, perpetrated in the Ras al-Nabaa district of Baniyas causing hundreds of Sunni residents to flee their homes.[5] According to one opposition report, a total of 77 civilians, including 14 children, were killed.[6] Another two opposition groups documented, by name, 96–145 people who are thought to have been executed in the district.[7][8] Four pro-government militiamen and two soldiers were also killed in the area in clashes with rebel fighters.[9]

Climate

Baniyas has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa). Rainfall is higher in winter than in summer. The average annual temperature in Baniyas is 19.3 °C (66.7 °F). About 862 mm (33.94 in) of precipitation falls annually.

| Climate data for Baniyas | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

29.1 (84.4) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

30.3 (86.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

9.2 (48.6) |

14.7 (58.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 159 (6.3) |

147 (5.8) |

123 (4.8) |

50 (2.0) |

26 (1.0) |

2 (0.1) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

12 (0.5) |

49 (1.9) |

94 (3.7) |

198 (7.8) |

862 (33.9) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org,Climate data | |||||||||||||

Bishopric

The bishopric of Balanea was a suffragan of Apamea, the capital of the Roman province of Syria Secunda, as is attested in a 6th-century Notitiae Episcopatuum.[10] When Justinian established a new civil province, Theodorias, with Laodicea as metropolis, Balanea was incorporated into it, but continued to depend ecclesiastically on Apamea, till it obtained the status of an exempt bishopric directly subject to the Patriarch of Antioch.[2]

Its first known bishop, Euphration, took part in the Council of Nicaea in 325 and was exiled by the Arians in 335 later Timotheus was at both the Robber Council of Ephesus in 449 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451. In 536, Theodorus was one of the signatories of a letter to the emperor Justinian against Severus of Antioch and other non-Chalcedonians. Stephanus participated in the Second Council of Constantinople in 553.[11][12]

In the Crusades period, Balanea became a Latin-Rite see, called Valenia or Valania in the West. It was situated within the Principality of Antioch and was subject to the Latin-Rite metropolitan see of Apamea, whose archbishop intervened in the nomination of bishops of the suffragan see in 1198 and 1215.[13][14][15] For reasons of security, the bishop lived in Margat Castle.[2]

No longer a residential bishopric, Balanea is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[16]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baniyas. |

![]()

- Strabo, XVI, 753

- Siméon Vailhé, "Balanaea" in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1907)

- "Syrians flee 'massacres' in Baniyas and al-Bayda," BBC (4 May 2013). Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- "At least 62 bodies found in Syria's Banias: watchdog". Bangkokpost.com. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- "Syrians flee coastal town after mass killings". Aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- Jim Muir (2013-05-04). "Syrians flee 'massacres' in Baniyas and al-Bayda". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- The Violations Documenting Center in Syria. "VDC Martyrs". Vdc-sy.info. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- "145 civilians (34 children, 40 women, 71 men) killed in the Banias massacre". Facebook.com. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- "Death toll for Friday 3/5/2013: More than 130 people killed yesterday in Syria". Facebook.com. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- Echos d'Orient 1907, p. 94.

- Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 921-924

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 436

- Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 8, p. 139

- Jean Richard, Note sur l'archidiocèse d'Apamée et les conquêtes de Raymond de Saint-Gilles en Syrie du Nord, in Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire, Year 1946, Volume 25, n° 1, pp. 103–108 (especially p. 107)

- Du Cange, Les familles d’outre-mer, Paris 1869, p. 814

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 845