Bakersfield, Vermont

Bakersfield is a town in Franklin County, Vermont, United States. The population was 1,322 at the 2010 census.[3]

Bakersfield, Vermont | |

|---|---|

Bakersfield Historical Society (formerly St. George's Catholic Church) | |

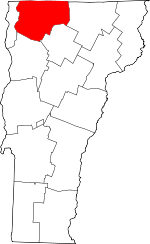

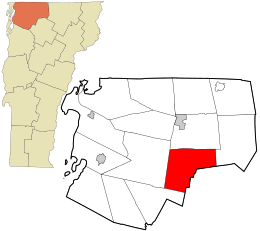

Location in Franklin County and the state of Vermont. | |

| Coordinates: 44°47′18″N 72°47′52″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Vermont |

| County | Franklin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 44.6 sq mi (115.6 km2) |

| • Land | 44.5 sq mi (115.3 km2) |

| • Water | 0.1 sq mi (0.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 725 ft (221 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,322 |

| • Density | 30/sq mi (11.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 05441 |

| Area code(s) | 802 |

| FIPS code | 50-02500[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1462031[2] |

| Website | townofbakersfield |

Geography

Bakersfield is located in southeastern Franklin County, bordered by Lamoille County to the southeast. Vermont Route 108 passes through the center of town, leading north to Enosburg Falls and south to Jeffersonville. Vermont Route 36 leads west from the center of Bakersfield to St. Albans, the Franklin County seat.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Bakersfield has a total area of 44.6 square miles (115.6 km2), of which 44.5 square miles (115.3 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.3 km2), or 0.24%, is water.[3] The town is part of the Missisquoi River watershed, draining to Lake Champlain. The Cold Hollow Mountains occupy the eastern end of the town, with a high point of 3,261 feet (994 m) just north of the Lamoille County line.

History

Early years

The town history began when Joseph Baker of Westborough, Massachusetts, the namesake for the village, bought 10,000 acres in 1791. Initial settlers were his son-in-law, Stephen Maynard, and his nephew Jonas Brigham, along with their families. Baker built grist and saw mills on Baker's Pond in 1794. Two years later Maynard built a tavern. In 1797, a school was established in a log cabin at the Post Road and Vermont 108. Five acres were deeded for the development of a town common and burying ground in 1804 by Joseph Baker. Maynard built a Federal style house north of the village to serve as the first post office in 1811.[4]

There were 12 school geographically-accessible districts in Bakersfield in 1839, due to the growth in the area. The town had grown to 1,258 residents in 1840.[4]

Academies

The settlement has been called an "old academy town" for the schools for college-bound students. Public speaking was encouraged for boys. The Bakersfield Academic Association was established in 1839, which built a three-story building to house a Methodist Church and the South Academy.[4] It was the first building for Bakersfield Academy, which opened in 1840.[5] Jacob Spaulding was hired as headmaster and Mary, his wife, was a drawing instructor and preceptress. In 1851, there were 271 students from New England, other parts of the United States, and Quebec. They had a staff of 14 people. The academy suffered a loss of reputation when Spaulding left the school in 1852 to become a principal for Barre and its well-endowed academy.[4]

In 1844 by Methodists wanted an academy on the north end of town. Unofficially called North Academy, the principal was Rev. H.J. Moore from northern New York.[4] The academies closed after a loss of students due to westward expansion, the creation of central public high schools, and the American Civil War.[4] In 1870, there were 70 students at Bakersfield Academy.[6] Bakersfield Academy is no longer in existence.[5]

Brigham Academy was built in 1879, with funding provided by Peter Bent Brigham, who left a $30,000 endowment for education, and his sister Sarah Brigham Jacobs who provided land and a $100,000 endowment for the academy. It was staffed by Jacob Spaulding, Rev. Dr. Wright from Bakersfield and of Oberlin College, and President Buckham of the University of Vermont. In 1900, an addition provided additional classroom, laboratories, and a gymnasium. Notable people who attended the academy include Warren Austin, the first U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and a U.S. senator and members of the Austin family of Highgate. In 1967, it closed as a high school. It continued to offer elementary and middle school education until 1987.[4]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 13 | — | |

| 1800 | 222 | 1,607.7% | |

| 1810 | 812 | 265.8% | |

| 1820 | 945 | 16.4% | |

| 1830 | 1,087 | 15.0% | |

| 1840 | 1,258 | 15.7% | |

| 1850 | 1,523 | 21.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,451 | −4.7% | |

| 1870 | 1,403 | −3.3% | |

| 1880 | 1,248 | −11.0% | |

| 1890 | 1,162 | −6.9% | |

| 1900 | 1,158 | −0.3% | |

| 1910 | 1,079 | −6.8% | |

| 1920 | 980 | −9.2% | |

| 1930 | 889 | −9.3% | |

| 1940 | 827 | −7.0% | |

| 1950 | 779 | −5.8% | |

| 1960 | 664 | −14.8% | |

| 1970 | 635 | −4.4% | |

| 1980 | 852 | 34.2% | |

| 1990 | 977 | 14.7% | |

| 2000 | 1,215 | 24.4% | |

| 2010 | 1,322 | 8.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[7] | |||

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 1,215 people, 439 households, and 326 families residing in the town. The population density was 27.2 people per square mile (10.5/km2). There were 504 housing units at an average density of 11.3 per square mile (4.4/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.86% White, 0.25% African American, 0.16% Native American, 0.08% Asian, and 1.65% from two or more races.

There were 439 households, out of which 40.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 60.8% were married couples living together, 9.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.7% were non-families. 18.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.77 and the average family size was 3.17.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 30.7% under the age of 18, 7.2% from 18 to 24, 28.9% from 25 to 44, 24.5% from 45 to 64, and 8.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.2 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $40,417, and the median income for a family was $41,688. Males had a median income of $31,563 versus $22,734 for females. The per capita income for the town was $15,678. About 6.1% of families and 9.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.3% of those under age 18 and 12.6% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

- Calvin H. Blodgett, mayor of Burlington, Vermont[8]

- Peter Bent Brigham, businessman, railroad executive, philanthropist, and founding donor of Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston and the Brigham Academy in Bakersfield

- D. Manfield Stearns, member of the Wisconsin State Assembly

- Lee Stephen Tillotson, Adjutant General of the Vermont National Guard

- William C. Wilson, Justice of the Vermont Supreme Court[9]

References

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Bakersfield town, Franklin County, Vermont". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- Hunt, Nancy (May 8, 2014). "History Space visits Bakersfield". Burlington Free Press. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- Federal Writers' Project (October 31, 2013). The WPA Guide to Vermont: The Green Mountain State. Trinity University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-59534-243-0.

- Vermont School Report. 1870. p. 160.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- "Bakersfield: Funeral of the Hon. Calvin H. Blodgett to be Held To-Day". Burlington Free Press. Burlington, VT. August 5, 1919. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Aldrich, Lewis Cass (1891). History of Franklin and Grand Isle Counties. Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co. p. 237.

Further reading

- Bakersfield Academy and Literary Association. Bakersfield, Vermont. 1850.