Bagnères-de-Bigorre

Bagnères-de-Bigorre (IPA: [baɲɛʁ də biɡɔʁ] (![]()

Bagnères-de-Bigorre | |

|---|---|

Subprefecture and commune | |

A general view of Bagnères-de-Bigorre | |

.svg.png) Coat of arms | |

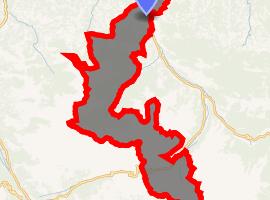

Location of Bagnères-de-Bigorre

| |

Bagnères-de-Bigorre  Bagnères-de-Bigorre | |

| Coordinates: 43°03′54″N 0°09′02″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Occitanie |

| Department | Hautes-Pyrénées |

| Arrondissement | Bagnères-de-Bigorre |

| Canton | La Haute-Bigorre |

| Intercommunality | Haute-Bigorre |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2013–2020) | Jean Bernard Sempastous |

| Area 1 | 125.86 km2 (48.59 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 7,253 |

| • Density | 58/km2 (150/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Bagnérais(e)[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 65059 /65200 |

| Elevation | 440–2,872 m (1,444–9,423 ft) (avg. 550 m or 1,800 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Name

The town was known in antiquity as Vicus Aquensis[3] (Latin for "watery neighborhood") and in the Middle Ages as Aquae Convenarum[4][5] ("Waters of the Comminges"). Its present name similarly means "Baths" (Occitan: Banheras) of Bigorre, the area of southwestern France once inhabited by the Bigorri and now forming most of the department of Hautes-Pyrénées. Either Bagnères-de-Bigorre or nearby Cieutat was apparently the "Begorra" attested in AD 400, which also derived from the ancient tribe.[6]

Heraldry

.svg.png) Arms of Bagnères-de-Bigorre |

Blazon: Gules, 3 towers Argent, the middle elevated, enclosed by a surrounding wall the same, all masoned, embattled, windowed, and ported of Sable. |

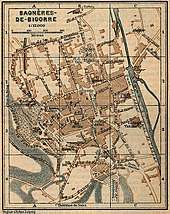

Geography

Location

Bagnères-de-Bigorre is located in the foothills of the Pyrenees partly in the valley of the Adour some 18 km (11 mi) southeast of Tarbes and 15 km (9 mi) east of Lourdes.

Hydrography

The Adour river flows through the north-east of the commune and the town flowing towards the north to eventually flow into the Atlantic Ocean at Bayonne. Numerous streams flow through the commune including the GaiVeste which forms the northern border as it flows north-east to join the Adour, the Oussouet which forms part of the western border as it flows north, the Ardazen which forms part of the eastern border as it flows east to join the Angoue, the Quartier par d'Abay which also forms part of the eastern border as it flows north-east gathering numerous tributaries, the Lhécou flows north from Lac Bleu just south of the commune to join the Quartier par d'Abay, the Garet forms part of the south-eastern border as it flows north from several lakes in the south of the commune (Lac de Caderolles, Lac de Gréziolles), the Adour d'Arizes flows south-east, and the Adour du Tourmalet flows east then north-east through the south of the commune, the hamlet of La Mongie and the Castillon Dam, to join the Adour d'Arizes forming the Adour de Gripp.[7]

Climate

Bagneres-de-Bigorre is relatively untouched by the west by south-west disturbances which blow out before the high border mountain range. It is however intensely exposed to north by north-west disturbances that collide with the terrain. This barrier effect is felt up to the foothills so that springs, autumns, and winters are cool and rainy while summers are often hot and particularly stormy.

History

Antiquity

Bigorre was conquered by the Roman general Julius Caesar in 56 BCE and incorporated into the province of Gallia Aquitania. Valerius Messala stamped out the last pockets of tribal resistance in 28 BC at a victory over the Campani on a hill in Pouzac.[5] The Romans subsequently settled and greatly frequented Vicus Aquensis's natural springs.[3] At its greatest extent, the Roman vicus covered about half as much area as the present community.[10] In the 4th-century reforms, the area around Vicus Aquensis became Aquitania Tertia or Novempopulana. It was sacked by the Visigoths amid the Barbarian Invasions.[3]

Middle Ages

The Visigoths in the area were displaced by the Franks following their defeat at the AD 507 Battle of Vouillé, but there are no documents or remains from the area to provide guidance on local history until 1171. Archaeologists have proposed that the city was destroyed at some point by an earthquake and abandoned following a plague outbreak in 580.[5]

The area had recovered by 1171, when Centule III, count of Bigorre, granted "Aquae Convenarum" a liberal charter.[11] The bill of rights and franchises lists four villages in the area protected by ramparts. By 1313, 800 "fires" (i.e., taxable homesteads) were recorded, making Bagnères as large as Tarbes, the county seat.[5] The town was a place of manufacture and trade, with only 40% directly involved in agriculture. Mills were erected on widened canals fed by the Adour; in addition to grinding wheat, they were used to stamp cauldrons, forge scythes, and tanning hides.[5] The Black Death reached the town in 1348. Amid the Hundred Years' War, the town fell into English possession in 1360 before suffering a second outbreak of plague the following year. Henri de Trastámara, an ally of the French king, plundered, ransomed, and razed the town in 1427. Two years later there were no more than 291 "fires" in Bagnères, although the town slowly repopulated.[5]

Renaissance

The town became even more commercial. In 1551, King Henry III of Navarre reformed the town's government, replacing its six consuls indirectly elected by a general assembly of the locals with a larger council of 40.[5]

The area's natural springs again rose to national prominence under Jeanne d'Albret,[3] who became queen of Navarre and countess of Bigorre upon her father Henry's death in 1555. She frequented the baths, prompting many other prominent visitors to follow.[11]

Already badly disposed towards Catherine de' Medici, queen regent of France, Jeanne converted to Calvinism on Christmas Day, 1560. She began attempting to impose the Reformation on her domains the following year. As the people of Bagnères remained largely Catholic, following the onset of the French Wars of Religion after the Massacre of Vassy, arrests for heresy began in 1562. While the Count of Montgomery was recovering Béarn from Catherine's allies in 1569, he went on to demand large ransoms from her other towns, including Bagnères. (It is unrecorded whether the people of Bagnères paid him, but he is recorded leaving the town unmolested and leaving for Gers.) The governor of Bagnères Antoine Beaudéan was killed by the Protestant warlord Lizier in an ambush near Pouzac in 1574.[5] By the end of the Wars of Religion, the town was ruined. Plague also returned in 1588. The outbreak ended following a religious procession prompted by the "Lighting of the Liloye", a Marian apparition at the Chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Médous.[5]

The ascension of Jeanne's son Henry as king of France in 1589 united his titles—including count of Bigorre—with the French monarchy.[5]

Early Modern era

_-_Fonds_Ancely_-_B315556101_A_COLSTON_004.jpg)

The plague struck Bagnères again in 1628, 1653, and 1654. Public health measures were taken, with most patients isolated in the Salut Valley. The disease did not reappear after December 1654.[5]

On 21 June 1660, strong earthquakes hit the town, continuing for three weeks. Only seven people were killed, but 150 houses were damaged and the springs initially dried up. This was only temporary, however, and the water flowed again sometime later.[5] Reconstruction was carried out with dimension stones from the Salut Quarry. This stone has the distinction of becoming like marble once polished, a feature that characterized the architecture of the town afterwards.

Hydrotherapy was gaining importance. There were 25 private businesses by 1787. In 1775, a convent building was transformed into a gambling establishment called the Vaux-Hall where there was also dining and dancing. This is the first casino in Bagnères.[5]

French Revolution

During the French Revolution, "moderate suspects" took refuge in the city from 1789 to 1793, ready to flee to Spain if the situation worsened. The departmental authorities were wary of the Bagnèrese, to whom they ascribed little civic or revolutionary spirit. In late 1793, before the hospitals in the southwest became saturated, the wounded were evacuated to spas. At Bagnères, the Saint Barthelemy Hospice, the Uzer and Lanzac houses, and the Hospice of the Médous Capuchins were used as military hospitals.[5]

Industrialization

In the 19th century, the hydrotherapy offered by Bagnères's spas was reckoned particularly effective for digestive complaints[3] but the private spas were growing more decrepit. In response, the municipality organized the construction of a Grand Thermal Spa (the "Thermes"), which was completed in 1828.[5] By the 1870s, the tourists would double the town's population of c. 9500 during the "season", which ran from May until about the end of October.[3] The casino also opened its own spa, the "Néothermes".[11]

The supply of marble became a pillar of the local economy, with the expansion of the Géruzet marble works making it one of the largest in France from 1829 to 1880. In the 1870s, the industry employed a thousand people.[5] Slate was also quarried.[11] Dominique Soulé expanded his business from an old mill purchased in 1862, the same year the town was connected to the Midi Railway.[5] The town also produced woolen and worsted cloth, leather, pottery, and toys.[3] A local specialty was barège, a light fabric of mixed silk and wool.[11]

The demolition of the city's walls allowed the completion of ring roads around the town,[5] and the town was the site of tribunals of first instance and of commerce.[11]

20th century

The town's population had declined to around 7000 at the onset of the First World War,[11] which resulted in the expansion of industry in Bagnères, particularly in the field of railway rolling stock. The marble industry collapsed but mechanical and textile industries replaced it. The share of hydrotherapy in the economy also decreased. In June 1944, during the Second World War, a punitive expedition of a company of SS murdered 32 in the town and hundreds more in the valley in retaliation against the actions of the resistance in the region.[5]

The postwar period saw rapid urban growth, particularly in the 1960s. Rural areas of the commune disappeared. The territory was occupied by dwellings to the borders of the neighbouring communes of Gerde and Pouzac which also become urban.[5]

At the end of the 20th century industrial activity decreased. The thermal spa guests were always present and new jobs were created by the implementation of the regional Centre for Reeducation and Rehabilitation, a large retirement home, and a nursing home.[5]

Administration

| From | To | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1781 | 1784 | Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Pambrun |

| 1787 | 1790 | Dumoret |

| 1790 | 1791 | Lebrun |

| 1790 | 1790 | de Cazebonne |

| 1791 | 1792 | Etienne Xavier Salaignac |

| 1792 | 1794 | Pierre Guchan |

| 1794 | 1795 | Jean-Louis Rousse |

| 1795 | 1795 | Bonnet |

| 1795 | 1795 | Dabbadie |

| 1795 | 1797 | Jean-Jacques Gaye |

| 1797 | 1799 | Dussert |

| 1799 | 1799 | Jean-Jacques Gaye |

| 1799 | 1800 | Costallat |

| 1800 | 1801 | Jean-Marie Sarrabeyrouse |

| 1801 | 1806 | Etienne Louis Salaignac |

| 1806 | 1806 | Piera |

| 1806 | 1815 | Paul Alexandre de Joulas |

| 1815 | 1816 | Bertrand Pinac |

| 1816 | 1817 | Achille d'Uzer |

| 1817 | 1830 | Jean Alexandre Duffourc d'Antist |

| 1830 | 1831 | Jean-Pierre Dumont |

| 1831 | 1835 | Aristide Lasserre |

| 1835 | 1835 | Jean-Pierre Dumont |

| 1835 | 1838 | Aristide Lasserre |

| 1838 | 1842 | Louis Dumoret |

| 1842 | 1848 | Jean-Baptiste Dauphole |

| 1848 | 1848 | François Soubies |

| 1848 | 1848 | Ariste Pambrun |

| 1848 | 1870 | Clément Cyprien d'Uzer |

| 1870 | 1871 | Mathieu Gaye |

| 1871 | 1873 | Jean-Jacques Dumoret |

| 1873 | 1881 | Dominique Jean-Marie Cardailhac |

| 1884 | 1889 | Robert de Puysegur |

| 1889 | 1901 | Jean-Marie Dejeanne |

| 1901 | 1912 | Bertrand Fortassin |

| 1912 | 1914 | Louis Lafforgue |

| 1914 | 1915 | Jean Lhez |

| 1915 | 1918 | Jean-Marie Cougombles |

| 1918 | 1919 | Jean Lhez |

| 1919 | 1935 | Prosper Nogues |

| 1935 | 1941 | Henri Suberbie |

- Mayors from 1941

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941 | 1944 | René Sühner | ||

| 1944 | 1945 | Joseph Domec | ||

| 1945 | 1958 | Joseph Meynier | ||

| 1958 | 1965 | Raymond Compagnet | ||

| 1965 | 1977 | André de Boysson | ||

| 1977 | 1989 | Eugène Toujas | ||

| 1989 | 2013 | Rolland Castells | ||

| 2013 | 2020 | Jean Bernard Sempastous |

(Not all data is known)

Twinning

Bagnères-de-Bigorre has twinning associations with:[13]

Intercommunality

The Community of communes of Haute-Bigorre (CCHB) was created in December 1994 to support joint development projects. It has been allocated a general grant for operations by the State and large grants by the General Council, the Regional Council, the State, and by Europe. Its skills are in:

- Economic development (businesses, trades, commercial fabrics...);

- Services to the elderly, children, and the disabled;

- Protection and enhancement of the environment;

- Selective waste collection;

- Housing and living Environment policy;

- Land development;

- Tourism.

Health

Bagnères-de-Bigorre has a regional hospital which has 25 beds for medicine, 20 beds for longer stays (4 of aftercare for alcohol withdrawal), and 220 beds for rehabilitation and physical medicine (25 places for day hospitalization). On the Castelmouly site (accommodation for the dependent elderly) the capacity is 142 beds plus 2 temporary, 36 long-stay beds, and 8 day care places for people with Alzheimer's disease or related disorders. The town also has a famous thermal baths.

Education

Schools in the commune are in the school district of the Academy of Toulouse.

The commune has three kindergartens (Clair Vallon, Carnot, and Achard), and six elementary schools (Calandreta of Banhèras (Occitan School), Jules Ferry, Pic du Midi, Carnot, Lesponne, les Palomières, and Saint Vincent).

The General Council manages the Colleges of Blanche Odin (formerly city school Achard) and Saint Vincent while the region supports the Victor Duruy high school.

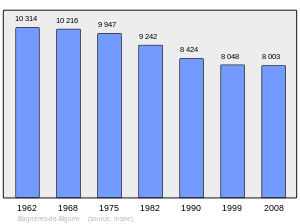

Demography

In 2010 the commune had 8,047 inhabitants. The evolution of the number of inhabitants is known from the population censuses conducted in the commune since 1793. From the 21st century, a census of communes with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants is held every five years, unlike larger communes that have a sample survey every year.[lower-alpha 1]

| 1793 | 1800 | 1806 | 1821 | 1831 | 1836 | 1841 | 1846 | 1851 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4,440 | 5,656 | 6,001 | 6,834 | 7,586 | 8,108 | 8,448 | 8,467 | 8,485 |

| 1856 | 1861 | 1866 | 1872 | 1876 | 1881 | 1886 | 1891 | 1896 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8,885 | 9,169 | 9,433 | 9,464 | 9,508 | 9,498 | 9,248 | 8,638 | 8,837 |

| 1901 | 1906 | 1911 | 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | 1946 | 1954 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8,671 | 8,591 | 8,455 | 8,261 | 8,880 | 9,211 | 8,633 | 9,941 | 11,044 |

| 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 | 2010 | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10,314 | 10,216 | 9,947 | 9,242 | 8,424 | 8,048 | - | 8,047 | - |

Economy

The economy of Bagnères-de-Bigorre is mainly in the secondary sector, at one time including railway materials, but Hydrotherapy and tourism are the main activities in the commune.

Industries

Today there are many SMEs and SMIs specializing in electrical equipment, mechanical, and aerospace industries located in the commune.

There are Four commercial zones of activity:

- The Dominique Soulé Business Park: an area of over 11 hectares with 14 companies (400 jobs). The main companies are:

- CFD Bagnères (formerly Constructions Ferroviaires de Bagnères ex Soulé),

- Novexia,

- Pommier,

- Nouvelle Bagnères Aéro,

- Protoplane – Avenir Composites,

- Bigorre Ingénierie.

- The Adour Industrial Zone: an area of around 16 hectares with 23 companies (280 jobs). The main companies are:

- Electraline CBB,

- Adour Industries,

- Duteil Arnauné sas,

- Spem Aero,

- Industrial Cabling Installations Pyrenees (MCIP).

- The Haute-Bigorre Business park: an area of over 4 hectares with 9 companies (70 jobs). The main companies are:

- Areva T & D,

- Amare Charpentes,

- Chaussons Matériaux,

- Adour Prothèses,

- Entreprise AOD

- The Haute-Bigorre Industrial Park: an area of more than 3 hectares with 3 companies (70 jobs). The main companies are:

- ABB Soulé Surge Protection – Hélita,

- Mang Metal Industries.

Hydrotherapy and tourism

The Grands Thermes de Bagnères-de-Bigorre (Grand Thermal Baths of Bagnères-de-Bigorre) are traditionally employed for treatment of rheumatism, nervous afflictions, indigestion, and other maladies.[11] The naturally-sourced waters vary in temperature from 90 to 135 °F (32 to 57 °C).[3]

Like most thermal cities, Bagnères-de-Bigorre has a casino. It is in the same building with the Aquensis thermal spa. The ski resort of La Mongie is also nearby.

- Thermalism and tourism gallery

_03.jpg) A Poster by Ulpiano Checa

A Poster by Ulpiano Checa- Building housing the Casino and Aquensis.

Winter Ski station of Tourmalet.

Winter Ski station of Tourmalet.

Transport

Access to the commune is by the D935 roads from Tarbes which passes through the north-eastern tip of the commune and the town before continuing southeast to Beaudéan. The D938 branches off the D935 in the town and goes north to Tournay. The D29 goes from Beaudéan to the centre of the commune with no exit. The D918 from Barèges passes through the southeast of the commune through the hamlet of La Mongie and continues northeast to Sainte-Marie-de-Campan. Apart from the town area the commune is mostly mountainous with few roads.[7]

The railway that connected Bagnères and Tarbes was closed in the late 1980s and the service is now provided by the TER bus from the old railway station which is now known as the bus station. The nearest airport is Tarbes-Lourdes-Pyrénées Airport some 30 kilometres (19 miles) to the north.

Culture and heritage

Civil heritage

The commune has several buildings and structures that are registered as historical monuments:

- The Uzer House at 1 Place d'Uzer (17th century)

- The Jean d'Albret House at 5 Rue du Vieux-Moulin (1539)

- The Tower of the Jacobins (14th century)

- Other sites of interest

- The Hospital contains a framed Painting: The Virgin of Carmel with the child Jesus and the Prophet Elie Tobie, and an angel (18th century)

- The Town Hall contains Library Shelves (19th century)

- The Grands Thermes de Bagnères-de-Bigorre (Grand Thermal Baths of Bagnères-de-Bigorre) were built in the Classical architecture of the 19th century using Pyrenees marble. It contains a Monument dedicated to the divinity of the Emperor Augustus (1st century)

- The Conservatoire botanique Pyrénéen

Religious heritage

The commune has two religious buildings and structures that are registered as historical monuments:

- The old Church of Saint John Portico (1280)

- The Church of Saint Vincent (1557)

Bagnères-de-Bigorre gallery

- Tower of the Jacobins

Church of Saint-Vincent

Church of Saint-Vincent- The Altar in the Saint Francis Chapel

- Cloister of Saint-Jean

- Covered Market

- Place de Strasbourg

Environmental heritage

- The Grottes de Médous (Médous caves) are natural caves accessible to visitors as well as a place of pilgrimage.

- Bagnères-de-Bigorre is the reference site for Theodoxus fluviatilis thermalis which was described in the 19th century by the malacologist Dominique Dupuy.

Museums

The town has had a museum since at least the early 20th century.[11]

The town has three museums:

- The Salies Museum of Fine Arts which lies below the oldest part of the thermal baths, the Dauphin baths dating from 1783

- The Salut Natural History Museum

- The Marble Museum created in 2007. This museum has more than 300 large samples of European marble.[29]

Cultural facilities

The city has several cultural centers:

- The Multimedia library

- The Municipal Cultural Center

- Le Maintenon Cinema

Many cultural events are organized:

- The Piano Pic Festival

- Chopin in Bagneres

- The Weekend of Street Art

- The À Voix Haute Music Festival (At a Loud Volume Music Festical)

- The High school girls video meeting (Ascension weekend)

- The Pyrenees Book Fair

The town has an orchestra called the Harmony Bagnéraise and a choir called La chorale des chanteurs montagnards (Chorus of Mountain Singers) which is the oldest secular choir in France and Europe [ref. required].

Sports

The Stade Bagnérais is a French rugby union club who have long played in the First Division, twice reaching the final of the Championship of France (1979 and 1981), and which plays in Fédérale 1 in the Rugby Championship in France.

The town of Bagneres has several sports associations, school structures, a leisure center, and numerous sports facilities:

- 4 Gymnasiums: La Plaine, Henri Cordier, Jules Ferry, and Carnot;

- The Apollo Hall for Dojo;

- The André Boysson Swimming pool;

- Rugby and soccer fields: La Plains, Marcel Cazenave Sports Park, Cordier, and Bagnères-Pouzac SIVU Sports;

- Tennis Courts: inside and outside;

- The Municipal Equestrian Center;

- Bigorre Golf Course (in Pouzac);

- The Adour Artificial whitewater;

- A Fronton in the Sports Park;

- A Skatepark;

- Bédat Shooting Range;

- A range of mountain activities at Tourmalet

In 2008 and 2013 Bagnères-de-Bigorre was a stage in the Tour de France:

- 2008 Tour de France: stage finish, won by Vladimir Efimkin

- 2013 Tour de France: stage finish, won by Dan Martin

Worship

The Parish of Bagneres-de-Bigorre includes 17 communes in the diocese of Tarbes and Lourdes (Haut-Adour Sector).[30]

The Petit-Rocher Carmel was founded in 1833 by Mother Marie-des-Anges. Expelled in 1901, the Carmelites returned in 1921 and a new community was formed in 2009.[31]

There is also a temple of the Reformed Church built by Emilien Frossard in 1857. It is attached to the parish of Hautes-Pyrenees with Tarbes and Cauterets.

Notable residents

- The Bédat Family: came from Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- André Joseph Boussart (1758–1813): General of the Republican armies and of the Empire, died at Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Alfred Roland (1797–1874): composer and creator of the Conservatory of Music of Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Marie-Armand d'Avezac de Castera-Macaya (1798–1875): archivist and geographer, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Jean-Jacques Vignerte (1806–1870): Politician, died at Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Charles Dancla (1817–1907): violinist and composer, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Charles Duclerc (1812–1888): Politician, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Admiral Sir Albert Hastings Markham (1841–1918): British explorer and Royal Navy officer, designer of the flag of New Zealand, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Dominique Soulé (1847?-?): Founder of the railway materials industrial works in 1862 which carried his name until 1992

- Blanche Odin (1865–1957): Painter water-colourist, lived and died in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Julián Bourdeu (1870–1932): Journalist and Police commissary in Argentina, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Philadelphe de Gerde (1871–1952): Félibrige poet from Gerde who has a stele commemorating here opposite the thermal baths

- Marcellin Duclos (1879–1969): Opera singer (Baritone), born and died in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke (1883–1963): British Army officer, became Chief of the Imperial General Staff, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Pierre-Georges Latécoère (1883–1943): Industrialist and businessman, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Pierre Lamy de la Chapelle (Limoges 1892-Bagnères-de-Bigorre 1944): son of Dominique Soulé, pioneer of the ski station at La Mongie, founded the tennis club of Bagnères-de-Bigorre in 1920, originated the idea of serving the Pic-du-Midi with a cable car

- Tony Poncet (1918–1979): tenor, Opera singer and war veteran, lived in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Jean Gachassin (1941–): former French rugby player and president of the Fédération française de tennis, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Jean-Louis Bruguès (1943–): Archbishop, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Roland Bertranne (1949–): former rugny player who played at Stade Bagnérais

- Jean-Paul Betbèze (1949–): economist, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Jean-Michel Aguirre (1951–): international Rugby Union player and former player for Stade Bagnérais

- Yves Duhard (1955–): Rugby Union player, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Wilfrid Forgues (1969–) and Frank Adisson (1969–): Olympic champions in Canoeing in 1996

- Sophie Theallet (1964–), Fashion designer, born in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- The Société Ramond: founded at a meeting between Henry Russell, Charles Packe, Farnham Maxwell-Lyte, and Emilien Frossard in 1865, and named after Louis Ramond de Carbonnières, based in Bagnères-de-Bigorre

- Tony Hawks: English writer and comedian, purchased a house in a village near Bagnères-de-Bigorre as told in his 2006 book A Piano in the Pyrenees.

See also

Notes

- At the beginning of the 21st century, the methods of identification have been modified by Law No. 2002-276 of 27 February 2002 Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, the so-called "law of local democracy" and in particular Title V "census operations" allows, after a transitional period running from 2004 to 2008, the annual publication of the legal population of the different French administrative districts. For communes with a population greater than 10,000 inhabitants, a sample survey is conducted annually, the entire territory of these communes is taken into account at the end of the period of five years. The first "legal population" after 1999 under this new law came into force on 1 January 2009 and was based on the census of 2006.

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Inhabitants of Hautes-Pyrénées", Habitants (in French)

- EB (1878).

- Nègre (1990), p. 296.

- "Discover the Town: History", Official website of the ville de Bagnères-de-Bigorre (in French), retrieved 19 December 2010

- Nègre (1990), p. 59.

- "Bagnères-de-Bigorre", Google Maps

- Géoportail, IGN (in French)

- Mayoux, Philippe, Bagnères-de-Bigorre: History of a Spa Town (in French), Alan Sutton

- Mayoux,[9] cited by the town's official website.[5]

- EB (1911).

- List of Mayors of France (in French)

- National Commission for Decentralised cooperation (in French)

- Malvern Observator

- North-east town to say 'bonjour' to its new French twin - Evening Express

- Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00095339 Uzer House at 1 Place d'Uzer (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00095338 Jean d'Albret House at 5 Rue du Vieux-Moulin (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00095340 Tower of the Jacobins (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM65000101 Painting: The Virgin of Carmel with the child Jesus and the Prophet Elie Tobie, and an angel (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM65000100 Library Shelves (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM65000099 Monument dedicated to the divinity of the Emperor Augustus (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00095336 Church of Saint John Portico (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00095337 Church of Saint Vincent (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM65000098 2 Confessionals (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM65000097 Baptismal font enclosure and Group Sculpture: Baptism of Christ (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM65000096 Altar in the Saint Francis Chapel (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM65000095 Stoup (in French)

- Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM65000094 Pulpit (in French)

- Museums of Bagnères, consulted on 19 December 2010. (in French)

- Bagnères-de-Bigorre on the diocese of Tarbes and Lourdes website, consulted on 3 December 2014. (in French)

- Christian Family, No. 1829, 2–8 February 2013, p. 28-30 (in French)

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 202

- Nègre, Ernest (1990), General Toponymy of France (in French), Librairie Droz, ISBN 2-60002-883-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bagnères-de-Bigorre. |