Bacău

Bacău (UK: /ˈbækaʊ/ BAK-ow,[3] US: /bəˈkaʊ/ bə-KOW,[3][4][5] Romanian: [baˈkəw] (![]()

Bacău | |

|---|---|

.jpg)    From top, left to right: Ascention Cathedral of Bacău, Public library (Old City Hall), St. Nicholas Cathedral, Cancikov park, Oituz Heroes monument, County Prefecture. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

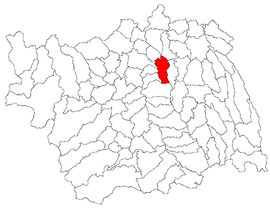

Location in Bacău County | |

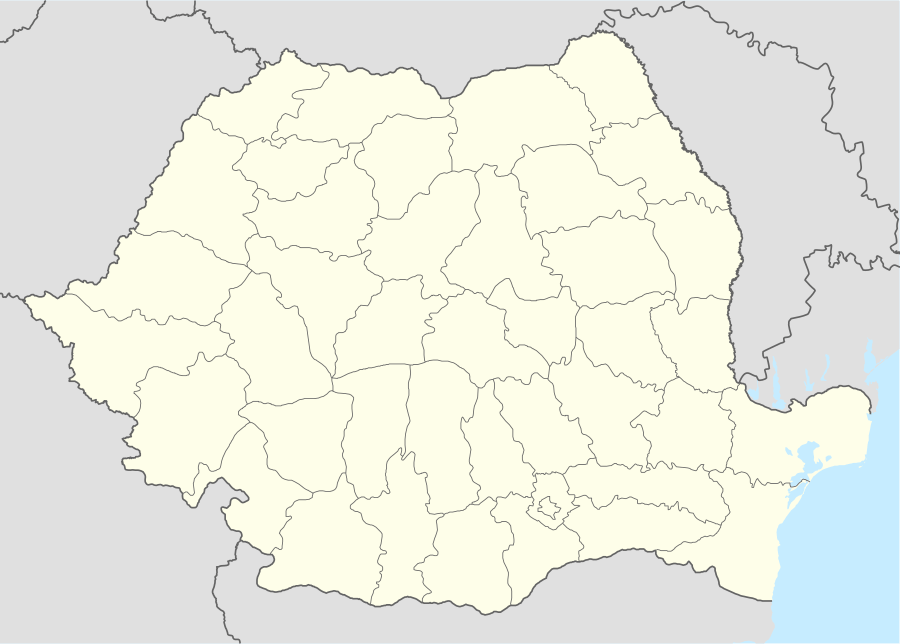

Bacău Location in Romania | |

| Coordinates: 46°35′N 26°55′E | |

| Country | |

| County | Bacău |

| Established | 1408 (first official record) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Cosmin Necula[1] (PSD) |

| Area | 43.19 km2 (16.68 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 165 m (541 ft) |

| Population (2011)[2] | 144,307 |

| • Density | 3,300/km2 (8,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET/EEST (UTC+2/+3) |

| Postal code | 600xxx |

| Area code | (+40) 234 |

| Vehicle reg. | BC |

| Website | municipiulbacau.ro |

Etymology

The town's name, which features in Old Church Slavonic documents as Bako, Bakova or Bakovia, comes most probably from a personal name.[6] Men bearing the name Bakó or Bako are documented in medieval Transylvania[7] and in 15th-century Bulgaria, but according to Victor Spinei the name itself is of Turkic – most probably of Cuman or Pecheneg – origin.[8] Nicolae Iorga believes that the city's name is of Hungarian origin (as Adjud and Sascut).[9] Another theory suggests that the town's name has a Slavic origin, pointing to the Proto-Slavic word byk, meaning "ox" or "bull", the region being very suitable for raising cattle; the term, rendered into Romanian alphabet as bâc, was probably the origin of Bâcău.[10] In German it is known as Bakau, in Hungarian as Bákó and in Turkish as Baka.

History

Similarly to most urban centers in Moldavia, Bacău emerged on a ford that allowed water passage.[11] There is archaeological evidence of human settlement in the centre of Bacǎu (near Curtea Domneascǎ) dating from the 6th and the 7th centuries; these settlements were placed over older settlements from the 4th and the 5th centuries. A number of vessels found here are ornamented with crosses, hinting that the inhabitants were Christians.[12] Pechenegs and Cumans controlled the Bistrița valley during the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries.[13] Colonists played a significant role in the development of the town.[14] Archaeological finds, some surface or semi-buried dwellings from the second half of the 15th century, suggest that Hungarians started to settle in the region after 1345–1347 when the territory was under the control of the Kingdom of Hungary.[15] They mainly occupied the flat banks of the river Bistrița.[16] Discoveries of a type of 14th-century grey ceramic that has also been found in Northern Europe also suggests the presence of German colonists from the north.[17] Originally the town focused around the Roman Catholic community that settled near a regular local market frequented by the population of the region on the lower reaches of the river.[7]

The town was first mentioned in 1408 when Prince Alexander the Good of Moldavia (1400–1432) listed the customs points in the principality in his privilege for Polish merchants.[18][19] The customs house in the town is mentioned in Old Church Slavonic as krainee mîto ("the customs house by the edge") in the document which may indicate that it was the last customs stop before Moldavia's border with Wallachia.[20] An undated document reveals that the şoltuz in Bacău, that is the head of the town elected by its inhabitants, had the right to sentence felons to death, at least for robberies, which hints to an extended privilege, similar to the ones that royal towns in the Kingdom of Hungary enjoyed.[21][22] Thus this right may have been granted to the community when the territory was under the control of the Kingdom of Hungary.[7] The seal of Bacău was oval which is exceptional in Moldavia where the seals of other towns were round.[23]

Alexander the Good donated the wax collected as part of the tax payable by the town to the nearby Orthodox Bistrița Monastery.[24] It was most probably his first wife named Margaret who founded the Franciscan Church of the Holy Virgin in Bacău.[25] But the main Catholic church in the town was dedicated to Saint Nicholas.[7] A letter written by John of Rya, the Catholic bishop of Baia refers to Bacău as a civitas which implies the existence of a Catholic bishopric in the town at that time.[25][26] The letter also reveals that Hussite immigrants who had undergone persecutions in Bohemia, Moravia, or Hungary were settled in the town and granted privileges by Alexander the Good.[27]

The monastery of Bistrița was also granted the income from the customs house of Bacău in 1439.[28] In 1435 Stephen II of Moldavia (1433–1435, 1436–1447) requested the town's judges not to hinder the merchants of Brașov, an important center of the Transylvanian Saxons in their movement.[29][30] From the 15th century ungureni, that is Romanians from Transylvania began to populate the area north of the marketplace where they would erect an Orthodox church after 1500.[7] A small residence of the princes of Moldova was built in the town in the first half of the 15th century.[31] It was rebuilt and extended under Stephen III the Great of Moldavia (1457–1504) who also erected an Orthodox church within it.[31] But the rulers soon began to donate the neighboring villages that had thereto supplied their local household to monasteries or noblemen.[32] Thus the local princely residence was abandoned after 1500.[33]

The town was invaded and destroyed more than one time in the 15th and 16th centuries.[33] For example, in 1467 King Matthias I of Hungary during his expedition against Stephen the Great set fire to all towns, among them Bacău in his path.[34] The customs records of Brașov shows that few merchants from Bacău crossed the Carpathian Mountains into Transylvania after 1500, and their merchandise had no particularly high value which suggests that the town was declining in this period.[33]

The Catholic bishop of Argeș whose see in Wallachia had been destroyed by the Tatars moved to Bacău in 1597.[33][35] From the early 17th century the bishops of Bacău were Polish priests who did not reside in the town, but in the Kingdom of Poland.[36] They only travelled time to time to their see in order to collect the tithes.[36]

According to Archbishop Marco Bandini's report of the canonical visitation of 1646, the şoltuz in Bacău was elected among Hungarians one year, and another, among Romanians.[7][37] The names of most of 12 inhabitants of the town recorded in 1655 also indicate that Hungarians still formed their majority group.[33] In 1670 Archbishop Petrus Parcevic, the apostolic vicar of Moldavia concluded an agreement with the head of the Franciscan Province of Transylvania on the return of the Bacău monastery to them in order to ensure the spiritual welfare of the local Hungarian community.[37][38] But the Polish bishop protested against the agreement and the Holy See also refused to ratify it.[37][39]

Due to the frequent invasions by foreign armies and plundering by the Tatars in the 17th century, many of its Catholic inhabitants abandoned Bacău and took refuge in Transylvania.[40] But in 1851 the Catholic congregation in the town still spoke, sang, and prayed in Hungarian.[41]

The first paper mill in Moldavia was established in the town in 1851.[42] The town was declared a municipality in 1968.[42]

Politics

The local authority in the city is split between the Mayor and the Local council. Between 1950 and 1968 the city was governed by the Sfatul popular (People's Council). It replaced the local Provisional Committee (Romanian: Comitetul Provizori), which functioned from 1948 to 1950, based on the Law of the People's Councils, no. 17/1949.[43]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 16,187 | — |

| 1912 | 18,846 | +16.4% |

| 1930 | 31,138 | +65.2% |

| 1941 | 38,965 | +25.1% |

| 1948 | 34,461 | −11.6% |

| 1956 | 54,138 | +57.1% |

| 1966 | 73,414 | +35.6% |

| 1977 | 127,299 | +73.4% |

| 1992 | 205,029 | +61.1% |

| 2002 | 175,500 | −14.4% |

| 2011 | 144,307 | −17.8% |

| Source: Census data, 1930–1948.[44] | ||

As of 2011 census data, Bacău has a population of 144,307, a decrease from the figure recorded at the 2002 census.[45] The ethnic makeup was as follows:

- Romanians: 97.93%

- Roma: 0.92%

- Hungarians: 0.09%

- Jews: 0.03%

- Other: 0.34%

The Bacău metropolitan area, a project for the creation of an administrative unit to integrate Bacău with the nearby communes, would have a population of some 190,000.

Transportation

The city is about 300 kilometres (186 miles) North of Bucharest. It is served by Bacău International Airport which provides direct links with the Romanian capital, Bucharest, and with 10 cities in Europe. Bacău air traffic control centre is one of Europe's busiest, as it handles transiting flights between the Middle and Near East and South Asia to Europe and across the Atlantic.

The Bacău railway station (Gara Bacău) is one of the busiest in Romania; it has access to the Romanian railway main trunk number 500. Thus the city is connected to the main Romanian cities; the railway station is an important transit stop for international trains from Ukraine, Russia, and Bulgaria.

The city has access to the DN2 road (E85) that links it to the Romanian capital, Bucharest (to the South) and the cities of Suceava and Iași (to the North). The European route E574 is an important access road to Transylvania and the city of Brașov. The city is also located at the intersection of several national roads of secondary importance.

Culture

Bacău has a public university and several colleges. Two major Romanian poets, George Bacovia and Vasile Alecsandri were born here. The "Mihail Jora" Athenaeum and a Philharmonic Orchestra are located here, as well as the "G. Bacovia" Dramatic Theater and a Puppet Theater. Around Christmas every year, a Festival of Moldavian Winter Traditions takes place, reuniting folk artists from all the surrounding regions. The exhibition "Saloanele Moldovei" and the International Painting Camp at Tescani, near Bacău, reunite important plastic artists from Romania and from abroad. The local History Museum, part of the Museum Complex "Iulian Antonescu" has an important collection of antique objects from ancient Dacia. The city also has an astronomical observatory, The Victor Anestin Astronomical Observatory.

Jewish community

The 1772-1774 Census registered 5 Jewish families, the 1820 Census registered 108 families. The 1852 Census registered 504 Jewish inhabitants. The 1930 Census registered 9424 Jewish inhabitants. The first mentions about Jewish inhabitants are from the beginning of the 18th century. The Register of Chevra Kadisha begins with the year 1774. The first leader of the Community is mentioned in 1794. The community was officially recognized in 1857.

Before World War I, the number of Jews was almost equal to that of Romanians in Bacău. According to the 1930 census, after some of the village population was in town, Bacău had 19,421 who have declared are Romanian, 9,424 declared Jews, 822 Hungarians and 406 German.

The first synagogue would be built in Bacău in 1820. In 1841 Jews who observe the current Habad Hasidic built another Sinagoga. In 1864 there were 14 functioning synagogues in Bacău. Among the most notable being Synagogue Burah Volf, Furriers Synagogue, Synagogue Alter Ionas and tanners. "In 1880, in Bacău we had 21 synagogues and prayer houses. In 1916 we were active following synagogues Froim Aizic, Alter Leib, Itzik Leib Brill, Lipscani, the Tailors Young, coachmen, Shoemakers Synagogue, Cerealista, masonry, Rabbi Israel Synagogue, "Brotherhood of Zion" Snap Synagogue Saima Cofler itself and Der Mariesches SIL.

After World War I, some synagogues were closed and others were razed. Some carried the names of rabbis deceased or people in life who had influence on the community: synagogue Wisman, synagogue Gaon Bețael Safran, synagogue Rabbi Blane, synagogue David Herșcovici, synagogue Filderman, the synagogue rabbi Wahramn, and synagogue Rabbi Lan.

[Information on the Nazi period missing, please give details.]

In December 2015, the new headquarters of the Jewish community was opened at 2 Erou Costel Marius Hasan St.[46]

International relations

Twin towns/Sister cities

Bacău is twinned with:

Sports

Athletics

- SCM Bacău

- CS Știința Bacău

- CSȘ Bacău

- CS Știința Bacău

- CSȘ Bacău

- CSȘ Bacău

- SCM Bacău

- Bridge Club Bacău

- FCM Bacău

- CS Aerostar Bacău

- CS FC Pambac Bacău

- FC Willy Bacău

- AS Clipa VIO Bacău

- Siretul Bacău

- LPS Bacău

- SCM Bacău

- CS Știința Bacău

Team Handball

- C.S. Știința Municipal Dedeman Bacău

- CS Știința Bacău

- CSȘ Bacău

- SCM Bacău

- Judo Club Royal Bacău

- SCM Bacău

- CS Știința Bacău

- CS Seishin Karate-Do Bacău

- Siretul Bacău

- Sfinx Club Karate-Do Bacau

- SCM Bacău

Modelism

- SCM Bacău

- CS Aerostar Bacău

- SCM Bacău (înot, sărituri în apă)

- LPS Bacău (înot)

- SCM Bacău

- ASTC Bistrița Bacău

- CSȘ Bacău

People

- Aaron Aaronsohn, agronomist, botanist and Zionist activist

- Vasile Alecsandri, poet

- Angela Alupei, rower

- George Apostu, sculptor

- Constantin Avram, academician

- Radu Beligan, actor, poet, essayist

- George Bacovia, poet

- Ovidiu Balan, conductor

- Dimitrie Berea, painter

- Ilie Boca, painter

- Julius Borcea, mathematician

- Constantin Cândea, chemist

- Vlad Chiricheș, footballer

- Radu Cosaşu, writer and activist

- Sile Dinicu, composer and conductor

- Ion Drăgoi, violinist

- Nicu Enea, painter

- Gabriela Firea, journalist and politician, mayor of Bucharest

- Mariana Zavati Gardner, poet

- Paul Grigoriu, journalist

- Nicolae Gropeanu, painter

- David Korner, communist militant, syndicalist and Romanian-French journalist of Jewish ethnicity

- Radu Lecca, double spy, journalist, fascist, antisemite, declared a war criminal by the communists

- Narcisa Lecuşanu, handball player

- Solomon Marcus, mathematician

- Agnès Matoko, model

- Dumitru Mazilu, politician

- Doina Melinte, athlete, Olympic gold medalist

- Mihaela Melinte, athlete

- Marius Mircu, journalist and memoirist

- Cornel Palade, humorist and TV host

- Costel Pantilimon, footballer

- Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu, Marxist intellectual and politician

- Vasile Pârvan, istoric, archaeologist, and academician

- Gabriela Potorac, gymnast

- Andrei Pricope, cellist

- Gheorghe Rădoi, communist politician, was married to Vasilica (Lica) Gheorghiu, daughter of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

- Monica Roșu, gymnast

- Mirela Rusu, double world champion in aerobic gymnastics

- Alexandru Șafran, Rabbi and senator

- Olga Tudorache, theater and film actress, university professor

- Anamaria Vartolomei, actress

- Nicolae Vermont, painter

Gallery

Mircea Cancicov memorial

Mircea Cancicov memorial Winter Festival

Winter Festival "Precista", detail

"Precista", detail "9th of May" Street

"9th of May" Street

See also

References

- "Results of the 2016 local elections". Central Electoral Bureau. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Populaţia stabilă pe judeţe, municipii, oraşe şi localităti componenete la RPL_2011" (in Romanian). National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Bacău". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- "Bacau". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- "Bacau". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 371.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 456.

- Spinei 2009, p. 342.

- Nicolae Iorga: Privilegiile șangăilor dela Târgu-Ocna, Extras din Analele Academiei Române, seria II, tom. XXXVII (1915), p. 246

- Gh. Ghibănescu - Ispisoace și Zapise. vol.VI, partea a II-a, Tipografia „Dacia” Iliescu, Grossu & Comp., Iași, 1926, pag.177

- Rădvan 2010, p. 332.

- Dan Gh. Teodor, Creștinismul la est de Carpati, Editura Mitropoliei Moldovei și Bucovinei, Iași, 1984, p. 25, 32, 160.

- Eugen Șendrea, Istoria municipiului Bacău, Bacău, Editura Vicovia, 2007, p.45-90.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 388.

- Rădvan 2010, pp. 388., 427., 455.

- Dobre 2009, p. 86.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 365.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 343.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, pp. lii., 32.

- Rădvan 2010, pp. 453-454.

- Rădvan 2010, pp. 399., 456.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 188.

- Rădvan 2010, pp. 406., 455.

- Rădvan 2010, pp. 416-417.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 455.

- Dobre 2009, p. 70.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 497.

- Rădvan 2010, pp. 373., 416.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 410.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, pp. lii., 48.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 454.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, pp. lii., 46.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 457.

- Rădvan 2010, p. 461.

- Benda 2002, p. 33.

- Benda 2002, p. 36.

- Benda 2002, p. 17.

- Pozsony 2002, pp. 94-95.

- Pozsony 2002, p. 95.

- Mărtinaș 1999, pp.36-38.

- Pozsony 2002, p. 102.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 32.

- Andrei Florin Sora, Comunizarea administrației românești: sfaturile populare (1949-1950), în „Revista istorică”, tom XXIII, nr. 3-4/2012

- Populatia RPR la 25 ianuarie 1948, p. 14

- "Population as of 20 October 2011" (in Romanian). INSSE. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- FOTO Evreii din Bacău şi-au inaugurat noul sediu, în prezenţa Marelui Rabin Rafael Shaffer şi a deputatului Aurel Vainer, preşedintele FCER

- Pessotto, Lorenzo. "International Affairs - Twinnings and Agreements". International Affairs Service in cooperation with Servizio Telematico Pubblico. City of Torino. Archived from the original on 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bacău. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bacău. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bacau. |

- Benda, Kálmán (2002). The Hungarians of Moldavia (Csángós) in the 16th–17th Centuries. In: Diószegi, László (2002); Hungarian Csángós in Moldavia: Essays on the Past and Present of the Hungarian Csángós in Moldavia; Teleki László Foundation - Pro Minoritate Foundation; ISBN 963-85774-4-4.

- Dobre, Claudia Florentina (2009). Mendicants in Moldavia: Mission in an Orthodox Land. AUREL Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938759-12-7.

- Mărtinaş, Dumitru (1999). The Origins of the Changos. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-98391-4-2.

- Pozsony, Ferenc (2002). Church Life in Moldavian Hungarian Communities. In: Diószegi, László (2002); Hungarian Csángós in Moldavia: Essays on the Past and Present of the Hungarian Csángós in Moldavia; Teleki László Foundation - Pro Minoritate Foundation; ISBN 963-85774-4-4.

- Rădvan, Laurenţiu (2010). At Europe's Borders: Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18010-9.

- Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

- Treptow, Kurt W.; Popa, Marcel (1996). Historical Dictionary of Romania. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-3179-1.