Aztec sun stone

The Aztec sun stone (Spanish: Piedra del Sol) is a late post-classic Mexica sculpture housed in the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, and is perhaps the most famous work of Aztec sculpture.[1] Its complex design and intricate glyphic language reflect that the stone is the product of a highly sophisticated culture. [2] It measures 358 centimetres (141 in) in diameter and 98 centimetres (39 in) thick, and weighs 24,590 kg (54,210 lb).[3] Shortly after the Spanish conquest, the monolithic sculpture was buried in the Zócalo, the main square of Mexico City. It was rediscovered on 17 December 1790 during repairs on the Mexico City Cathedral.[4] Following its rediscovery, the sun stone was mounted on an exterior wall of the Cathedral, where it remained until 1885.[5] Early scholars initially thought that the stone was carved in the 1470s, though modern research suggests that it was carved some time between 1502 and 1521.[6]

| Sun Stone | |

|---|---|

Sun Stone, at National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, Mexico | |

| Material | Basalt |

| Created | Sometime between 1502 and 1520 |

| Discovered | 17 December 1790 at El Zócalo, Mexico City |

| Present location | National Anthropology Museum (Mexico City) |

| Period | Post-Classical |

| Culture | Mexica |

History

The monolith was carved by the Mexica at the end of the Mesoamerican Postclassic Period. Although the exact date of its creation is unknown, the name glyph of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II in the central disc dates the monument to his reign between 1502–1520 AD.[7] There are no clear indications about the authorship or purpose of the monolith, although there are certain references to the construction of a huge block of stone by the Mexicas in their last stage of splendor. According to Diego Durán, the emperor Axayácatl "was also busy in carving the famous and large stone, very carved where the figures of the months and years, days 21 and weeks were sculpted".[8] Juan de Torquemada described in his Monarquía indiana how Moctezuma Xocoyotzin ordered to bring a large rock from Tenanitla, today San Angel, to Tenochtitlan, but on the way it fell on the bridge of the Xoloco neighborhood.[9]

The parent rock from which it was extracted comes from the Xitle volcano, and could have been obtained from San Ángel or Xochimilco.[10] The geologist Ezequiel Ordoñez in 1893 determined such an origin and ruled it as olivine basalt. It was probably dragged by thousands of people from a maximum of 22 kilometers to the center of Mexico-Tenochtitlan.[10]

After the conquest, it was transferred to the exterior of the Templo Mayor, to the west of the then Palacio Virreinal and the Acequia Real, where it remained uncovered, with the relief upwards for many years.[9] According to Durán, Alonso de Montúfar, Archbishop of Mexico from 1551 to 1572, ordered the burial of the Sun Stone so that "the memory of the ancient sacrifice that was made there would be lost".[9]

Towards the end of the 18th century, the viceroy Juan Vicente de Güemes initiated a series of urban reforms in the capital of New Spain. One of them was the construction of new streets and the improvement of parts of the city, through the introduction of drains and sidewalks. In the case of the then called Plaza Mayor, sewers were built, the floor was leveled and areas were remodeled. It was José Damián Ortiz de Castro, the architect overseeing public works, who reported the finding of the sun stone on 17 December 1790. The monolith was found half a yard (about 40 centimeters) under the ground surface and 60 meters to the west of the second door of the viceregal palace,[9] and removed from the earth with a "real rigging with double pulley".[9] Antonio de León y Gama came to the discovery site to observe and determine the origin and meaning of the monument found.[9] According to Alfredo Chavero,[11] it was Antonio who gave it the name of Aztec Calendar, believing it to be an object of public consultation. León y Gama said the following:

... On the occasion of the new paving, the floor of the Plaza being lowered, on December 17 of the same year, 1790, it was discovered only half a yard deep, and at a distance of 80 to the West from the same second door of the Royal Palace, and 37 north of the Portal of Flowers, the second Stone, by the back surface of it.

— León y Gama, as cited by Chavero[11]

León y Gama himself interceded before the canon of the Cathedral, José Uribe, in order that the monolith found would not be buried again due to its perceived pagan origin (for which it had been buried almost two centuries before).[12] León y Gama argued that in countries like Italy there was much that was invested in rescuing and publicly showcasing monuments of the past.[12] It is noteworthy that, for the spirit of the time, efforts were made to exhibit the monolith in a public place and also to promote its study.[12] León y Gama defended in his writings the artistic character of the stone, in competition with arguments of authors like Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, who gave lesser value to those born in the American continent, including their artistic talent.[12]

The monolith was placed on one side of the west tower of the Metropolitan Cathedral on 2 July 1791. There it was observed by, among others, Alexander von Humboldt, who made several studies on its iconography.[9] Mexican sources alleged that during the Mexican–American War, soldiers of the United States Army who occupied the plaza used it for target shooting, though there is no evidence of such damage to the sculpture.[9] Victorious General Winfield Scott contemplated taking it back to Washington D.C. as a war trophy, if the Mexicans did not make peace.[13]

In August 1855, the stone was transferred to the Monolith Gallery of the Archaeological Museum on Moneda Street, on the initiative of Dr. Jesús Sánchez, director of the same.[9] Through documents from the time, it is known of the popular animosity that caused the "confinement" of a public reference of the city.[9]

In 1964 the stone was transferred to the National Museum of Anthropology and History, where the stone presides over the Mexica Hall of the museum and is inscribed in various Mexican coins.

Before the discovery of the monolith of Tlaltecuhtli, deity of the earth, with measurements being 4 by 3.57 meters high, it was thought that the Sun Stone was the largest Mexica monolith in dimensions.

- Plaza Mayor of Mexico City by Pedro Guridi (c.1850) shows the sun disk attached to the side of the cathedral tower, it was placed there in 1790 when it was discovered and remained on the tower until 1885

The Swiss artist Johann Salomon Hegi painted the famous Paseo de las Cadenas in 1851, the Sun Stone is distinguishable below and to the right of the ash tree foliage

The Swiss artist Johann Salomon Hegi painted the famous Paseo de las Cadenas in 1851, the Sun Stone is distinguishable below and to the right of the ash tree foliage Image of the stone when it was in the Metropolitan Cathedral

Image of the stone when it was in the Metropolitan Cathedral The Stone of the Sun as it was exhibited in the National Museum, photograph taken in 1915

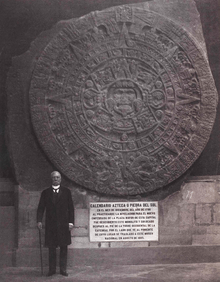

The Stone of the Sun as it was exhibited in the National Museum, photograph taken in 1915 Photograph from 1910 of the Sun Stone with Porfirio Díaz

Photograph from 1910 of the Sun Stone with Porfirio Díaz Photograph from 1917 of the Piedra del Sol with Venustiano Carranza

Photograph from 1917 of the Piedra del Sol with Venustiano Carranza

Physical description and iconography

.jpg)

The sculpted motifs that cover the surface of the stone refer to central components of the Mexica cosmogony. The state-sponsored monument linked aspects of Aztec ideology such as the importance of violence and warfare, the cosmic cycles, and the nature of the relationship between gods and man. The Aztec elite used this relationship with the cosmos and the bloodshed often associated with it to maintain control over the population, and the Sun Stone was a tool in which the ideology was visually manifested.[14]

Central disk

In the center of the monolith is often believed to be the face of the solar deity, Tonatiuh,[15] which appears inside the glyph for "movement" (Nahuatl: Ōllin), the name of the current era. Some scholars have argued that the identity of the central face is of the earth monster, Tlaltecuhtli, or of a hybrid deity known as Yohualtecuhtli who is referred to as the "Lord of the Night." This debate on the identity of the central figure is based on representations of the deities in other works as well as the role of the Sun Stone in sacrificial context, which involved the actions of deities and humans to preserve the cycles of time.[16] The central figure is shown holding a human heart in each of his clawed hands, and his tongue is represented by a stone sacrificial knife (Tecpatl).

Four previous suns or eras

The four squares that surround the central deity represent the four previous suns or eras, which preceded the present era, 4 Movement (Nahuatl: Nahui Ōllin). The Aztecs changed the order of the suns and introduced a fifth sun named 4 Movement after they seized power over the central highlands.[17] Each era ended with the destruction of the world and humanity, which were then recreated in the next era.

- The top right square represents 4 Jaguar (Nahuatl: Nahui Ōcēlotl), the day on which the first era ended, after having lasted 676 years, due to the appearance of monsters that devoured all of humanity.

- The top left square shows 4 Wind (Nahuatl: Nahui Ehēcatl), the date on which, after 364 years, hurricane winds destroyed the earth, and humans were turned into monkeys.

- The bottom left square shows 4 Rain (Nahuatl: Nahui Quiyahuitl). This era lasted 312 years, before being destroyed by a rain of fire, which transformed humanity into turkeys.

- The bottom right square represents 4 Water (Nahuatl: Nahui Atl), an era that lasted 676 years and ended when the world was flooded and all the humans were turned into fish.

The duration of the ages is expressed in years, although they must be observed through the prism of Aztec time. In fact the common thing to figures 676, 364 and 312 is that they are multiples of 52, and 52 years is the duration of 1 Aztec century, and that is why they can express a certain amount of Aztec centuries. Thus, 676 years are 13 Aztec centuries; 364 years are 7, and 312 years are 6 Aztec centuries.

Placed among these four squares are three additional dates, 1 Flint (Tecpatl), 1 Rain (Atl), and 7 Monkey (Ozomahtli), and a Xiuhuitzolli, or ruler's turquoise diadem, glyph. It has been suggested that these dates may have had both historical and cosmic significance, and that the diadem may form part of the name of the Mexica ruler Moctezuma II.[18]

First ring

The first concentric zone or ring contains the signs corresponding to the 20 days of the 18 months and five nemontemi of the Aztec solar calendar (Nahuatl: xiuhpohualli). It is important to note that the monument is not a functioning calendar, but instead uses the calendrical glyphs to reference the cyclical concepts of time and its relationship to the cosmic conflicts within the Aztec ideology.[19] Beginning at the symbol just left of the large point in the previous zone, these symbols are read counterclockwise. The order is as follows:

1. cipactli – crocodile, 2. ehécatl – wind, 3. calli – house, 4. cuetzpallin – lizard, 5. cóatl – serpent, 6. miquiztli – skull/death, 7. mázatl – deer, 8. tochtli – rabbit, 9. atl – water, 10. itzcuintli – dog, 11. ozomatli – monkey, 12. malinalli – herb, 13. ácatl – cane, 14. océlotl – jaguar, 15. cuauhtli – eagle, 16. cozcacuauhtli – vulture, 17. ollín – movement, 18. técpatl – flint, 19. quiahuitl – rain, 20. xóchitl – flower [20]

|

|

Second ring

The second concentric zone or ring contains several square sections, with each section containing five points. Directly above these square sections are small arches are said to be feather ornaments. Directly above these are spurs or peaked arches that appear in groups of four.[20] There are also eight angles that divide the stone into eight parts, which likely represent the sun's rays placed in the direction of the cardinal points.

Third and outermost ring

Two fire serpents, Xiuhcoatl, take up almost this entire zone. They are characterized by the flames emerging from their bodies, the square shaped segments that make up their bodies, the points that form their tails, and their unusual heads and mouths. At the very bottom of the surface of the stone, are human heads emerging from the mouths of these serpents. Scholars have tried to identify these profiles of human heads as deities, but have not come to a consensus.[20] One possible interpretation of the two serpents is that they represent two rival deities who were involved in the creation story of the fifth and current "sun", Queztalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca. The tongues of the serpents are touching, referencing the continuity of time and the continuous power struggle between the deities over the earthly and terrestrial worlds.[21]

In the upper part of this zone, a square carved between the tails of the serpents represents the date Matlactli Omey-Ácatl ("13-reed"). This is said to correspond to 1479, the year in which the Fifth Sun emerged in Teotihuacan during the reign of Axayácatl, and at the same time, indicating the year in which this monolithic sun stone was carved.[20]

Edge of stone

The edge of the stone measures approximately 8 inches and contains a band of a series of dots as well as what have been said to be flint knives. This area has been interpreted as representing a starry night sky.[20]

History of interpretations

| |

From the moment the Sun Stone was discovered in 1790, many scholars have worked at making sense of the stone's complexity. This provides a long history of over 200 years of archaeologists, scholars, and historians adding to the interpretation of the stone.[22] Modern research continues to shed light or cast doubt on existing interpretations as discoveries such as further evidence of the stone's pigmentation.[23] As Eduardo Matos Moctezuma stated in 2004:[20]

In addition to its tremendous aesthetic value, the Sun Stone abounds in symbolism and elements that continue to inspire researchers to search deeper for the meaning of this singular monument.

— Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, The Aztec Calendar and Other Solar Monuments

The earliest interpretations of the stone relate to what early scholars believed was its use for astrology, chronology, or as a sundial. In 1792, two years after the stone's unearthing, Mexican scholar Antonio de León y Gama wrote one of the first treatises on Mexican archaeology on the Aztec calendar and Coatlicue.[24] He correctly identified that some of the glyphs on the stone are the glyphs for the days of the month.[22] Alexander von Humboldt also wanted to pass on his interpretation in 1803, after reading Leon y Gama's work. He disagreed about the material of the stone but generally agreed with Leon y Gama's interpretation. Both of these men incorrectly believed the stone to have been vertically positioned, but it was not until 1875 that Alfredo Chavero correctly wrote that the proper position for the stone was horizontal. Roberto Sieck Flandes in 1939 published a monumental study entitled How Was the Stone Known as the Aztec Calendar Painted? which gave evidence that the stone was indeed pigmented with bright blue, red, green, and yellow colors, just as many other Aztec sculptures have been found to have been as well. This work was later to be expanded by Felipe Solís and other scholars who would re-examine the idea of coloring and create updated digitized images for a better understanding of what the stone might have looked like.[20] It was generally established that the four symbols included in the Ollin glyph represent the four past suns that the Mexica believed the earth had passed through.[25]

Another aspect of the stone is its religious significance. One theory is that the face at the center of the stone represents Tonatiuh, the Aztec deity of the sun. It is for this reason that the stone became known as the "Sun Stone." Richard Townsend proposed a different theory, claiming that the figure at the center of the stone represents Tlaltecuhtli, the Mexica earth deity who features in Mexica creation myths.[22] Modern archaeologists, such as those at the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, believe it is more likely to have been used primarily as a ceremonial basin or ritual altar for gladiatorial sacrifices, than as an astrological or astronomical reference.[5]

Yet another characteristic of the stone is its possible geographic significance. The four points may relate to the four corners of the earth or the cardinal points. The inner circles may express space as well as time.[26]

Lastly, there is the political aspect of the stone. It may have been intended to show Tenochtitlan as the center of the world and therefore, as the center of authority.[27] Townsend argues for this idea, claiming that the small glyphs of additional dates amongst the four previous suns—1 Flint (Tecpatl), 1 Rain (Atl), and 7 Monkey (Ozomahtli)—represent matters of historical importance to the Mexica state. He posits, for example, that 7 Monkey represents the significant day for the cult of a community within Tenochtitlan. His claim is further supported by the presence of Mexica ruler Moctezuma II's name on the work. These elements ground the Stone's iconography in history rather than myth and the legitimacy of the state in the cosmos.[28]

Connections to Aztec Ideology

The methods of Aztec rule were influenced by the story of their Mexica ancestry, who were migrants to the Mexican territory. The lived history was marked by violence and the conquering of native groups, and their mythic history was used to legitimize their conquests and the establishment of the capital Tenochtitlan. As the Aztecs grew in power, the state needed to find ways to maintain order and control over the conquered peoples, and they used religion and violence to accomplish the task.[29]

The state religion included a vast canon of deities that were involved in the constant cycles of death and rebirth. When the gods made the sun and the earth, they sacrificed themselves in order for the cycles of the sun to continue, and therefore for life to continue. Because the gods sacrificed themselves for humanity, humans had an understanding that they should sacrifice themselves to the gods in return. The Sun Stone's discovery near the Templo Mayor in the capital connects it to sacred rituals such as the New Fire ceremony, which was conducted to ensure the earth's survival for another 52-year cycle, and human heart sacrifice played an important role in preserving these cosmic cycles.[29] Human sacrifice was not only used in religious context; additionally, sacrifice was used as a military tactic to frighten Aztec enemies and remind those already under their control what might happen if they opposed the Empire. The state was then exploiting the sacredness of the practice to serve its own ideological intentions. The Sun Stone served as a visual reminder of the Empire's strength as a monumental object in the heart of the city and as a ritualistic object used in relation to the cosmic cycles and terrestrial power struggles.[30]

Modern use

The sun stone image is displayed on the obverse the Mexican 20 Peso gold coin, which has a gold content of 15 grams (0.4823 troy ounces) and was minted from 1917–1921 and restruck with the date 1959 from the mid 1940s to the late 1970s. Different parts of the sun stone are represented on the current Mexican coins, each denomination has a different section.

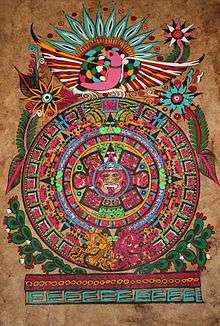

The sun stone image also has been adopted by modern Mexican and Mexican American/Chicano culture figures, and is used in folk art and as a symbol of cultural identity.[31]

Impact of Spanish Colonization

After the conquest of the Aztec Empire by the Spanish in 1521 and the subsequent colonization of the territory, the prominence of the Mesoamerican empire was placed under harsh scrutiny by the Spanish. The rationale behind the bloodshed and sacrifice conducted by the Aztec was supported by religious and militant purposes, but the Spanish were horrified by what they saw, and the published accounts twisted the perception of the Aztecs into bloodthirsty, barbaric, and inferior people.[32] The words and actions of the Spanish, such as the destruction, removal, or burial of Aztec objects like the Sun Stone supported this message of inferiority, which still has an impact today. The Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was covered by the construction of Mexico City, and the monument was lost for centuries until it was unearthed in 1790.[21] The reemergence of the Sun Stone sparked a renewed interest in Aztec culture, but since the Western culture now had hundreds of years of influence over the Mexican landscape, the public display of the monument next to the city's main cathedral sparked controversy. Although the object was being publicly honored, placing it in the shadow of a Catholic institution for nearly a century sent a message to some people that the Spanish would continue to dominate over the remnants of Aztec culture.[33]

Another debate sparked by the influence of the Western perspective over non-Western cultures surrounds the study and presentation of cultural objects as art objects. Carolyn Dean, a scholar of pre-Hispanic and Spanish colonial culture discusses the concept of “art by appropriation,” which displays and discusses cultural objects within the Western understanding of art. Claiming something as art often elevates the object in the viewer’s mind, but then the object is only valued for its aesthetic purposes, and its historical and cultural importance is depleted.[34] The Sun Stone was not made as an art object; it was a tool of the Aztec Empire used in ritual practices and as a political tool. By referring to it as a "sculpture"[34] and by displaying it vertically on the wall instead of placed horizontally how it was originally used[21], the monument is defined within the Western perspective and therefore loses its cultural significance. The current display and discussion surrounding the Sun Stone is part of a greater debate on how to decolonize non-Western material culture.

Other sun stones

There are several other known monuments and sculptures that bear similar inscriptions. Most of them were found underneath the center of Mexico City, while others are of unknown origin. Many fall under a category known as temalacatl, large stones built for ritual combat and sacrifice. Matos Moctezuma has proposed that the Aztec Sun Stone might also be one of these.[35]

Temalacatls

The Stone of Tizoc's upward-facing side contains a calendrical depiction similar to that of the subject of this page. Many of the formal elements are the same, although the five glyphs at the corners and center are not present. The tips of the compass here extend to the edge of the sculpture. The Stone of Tizoc is currently located in the National Anthropology Museum in the same gallery as the Aztec Sun Stone.

The Stone of Motecuhzoma I is a massive object approximately 12 feet in diameter and 3 feet high with the 8 pointed compass iconography. The center depicts the sun deity Tonatiuh with the tongue sticking out.[36]

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has another, viewable here. This one is much smaller, but still bears the calendar iconography and is listed in their catalog as "Calendar Stone". The side surface is split into two bands, the lower of which represents Venus with knives for eyes; the upper band has two rows of citlallo star icons.[36]

A similar object is on display at the Yale University Art Gallery, on loan from the Peabody Museum of Natural History. This object can be viewed here.[37] The sculpture, officially known as Aztec Calendar Stone in the museum catalog but called Altar of the Five Cosmogonic Eras,[36] bears similar hieroglyphic inscriptions around the central compass motif but is distinct in that it is a rectangular prism instead of cylindrical shape, allowing the artists to add the symbols of the four previous suns at the corners.[36] It bears some similarities to the Coronation Stone of Moctezuma II, listed in the next section.

Calendar iconography in other objects

The Coronation Stone of Motecuhzoma II (also known as the Stone of the Five Suns) is a sculpture measuring 55.9 x 66 x 22.9 cm (22 x 26 x 9 in[38]), currently in the possession of the Art Institute of Chicago. It bears similar hieroglyphic inscriptions to the Aztec Sun Stone, with 4-Movement at the center surrounded by 4-Jaguar, 4-Wind, 4-Rain, and 4-Water, all of which represent one of the five suns, or "cosmic eras". The year sign 11-Reed in the lower middle places the creation of this sculpture in 1503, the year of Motecuhzoma II's coronation, while 1-Crocodile, the day in the upper middle, may indicate the day of the ceremony.[38] The date glyph 1-Rabbit on the back of the sculpture (not visible in the image to the right) orients Motecuhzoma II in the cosmic cycle because that date represents "the beginning of things in the distant mythological past."[38]

The Throne of Montezuma uses the same cardinal point iconography[39] as part of a larger whole. The monument is on display at the National Museum of Anthropology alongside the Aztec Sun Stone and the Stone of Tizoc. The monument was discovered in 1831 underneath the National Palace[40] in Mexico City and is approximately 1 meter square at the base and 1.23 meters tall.[39] It is carved in a temple shape, and the year at the top, 2-House, refers to the traditional founding of Tenochtitlan in 1325 CE.[39]

The compass motif with Ollin can be found in stone alters built for the New Fire ceremony.[36] Another object, the Ceremonial Seat of Fire which belongs to the Eusebio Davalos Hurtado Museum of Mexica Sculpture,[36] is visually similar but omits the central Ollin image in favor of the Sun.

The British Museum possesses a cuauhxicalli which may depict the tension between two opposites, the power of the sun (represented by the solar face) and the power of the moon (represented with lunar iconography on the rear of the object). This would be a parallel to the Templo Mayor with its depictions of Huitzilopochtli (as one of the two deities of the temple) and the large monument to Coyolxauhqui.[36]

|

|

Coronation stone of Motecuhzoma II | ||||||||||||

See also

Notes and references

References

- "National Anthropology Museum, Mexico City, "Sun Stone"". Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- Carrasco, David L. (2012). The Aztects: A Very Short Introduction. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195379389.

- Ordóñez, Esequiel (1893). La roca del Calendario Azteca (Primera Edición edición). México: Imprenta del Gobierno Federal. pp. 326-331.

- Florescano, Enrique (2006). National Narratives in Mexico. Nancy T. Hancock (trans.), Raul Velasquez (illus.) (English-language edition of Historia de las historias de la nación mexicana, ©2002 [Mexico City:Taurus] ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3701-0. OCLC 62857841.

- Getty Museum, "Aztec Calendar Stone" getty.edu, accessed 22 August 2018

- Villela, Khristaan. "The Aztec Calendar Stone or Sun Stone", MexicoLore. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- Hassig, Ross (2001). "Reinterpreting Aztec Perspectives". Time, History, and Belief in Aztec and Colonial Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 48–69. ISBN 9780292731400.

- Moreno de los Arcos, Roberto (1967). "Los cinco soles cosmogónicos". Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl.

También estaba ocupado en labrar la piedra famosa y grande, muy labrada donde estaban esculpidas las figuras de los meses y años, días 21 y semanas

- López Luján, Leonardo (2006). "El adiós y triste queja del gran Calendario Azteca" (PDF). Arqueología Mexicana 78. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- "History in Stone".

- Chavero, Alfredo (1876). "Calendario Azteca: un ensayo arqueológico" (PDF). Imprenta de Jens y Zapiaine.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (2012). "La Piedra del Sol o Calendario Azteca". Escultura Monumental Mexica. Fondo de Cultura.

- Van Wagengen, Michael Scott. Remembering the Forgotten War: The Enduring Legacies of the U.S.-Mexican War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press 2012, pp. 25-26

- Brumfiel, Elizabeth (1998). "Huitzilopochtli's Conquest: Aztec Ideology in the Archaeological Record". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 8: 3–13. doi:10.1017/s095977430000127x.

- The public description by the National Anthropology Museum assigns the face to the fire god, Xiuhtecuhtli.

- Klein, Cecelia F. (March 1972). "The Identity of the Central Deity on the Aztec Calendar". The Art Bulletin. 58 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/00043079.1976.10787237 – via JSTOR.

- Villela, Khristaan; Michel Graulich (2010). "The Stone of the Sun". The Aztec Calendar Stone. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute. p. 258.

- Umberger, Emily. "The Structure of Aztec History". Archaeoastronomy IV, no. 4 (Oct–Dec 1981): 10–18.

- Kelin, Cecelia F. (March 1972). "The Identity of the central Deity on the Aztec Calendar". The Art Bulletin. 58 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/00043079.1976.10787237 – via JSTOR.

- Eduardo., Matos Moctezuma (2004). The Aztec calendar and other solar monuments. Solís Olguín, Felipe R. México, D.F.: Conaculta-Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia. pp. 13, 48–59, 68, 70, 72, 74. ISBN 9680300323. OCLC 57716237.

- Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel (2006). Handbook to: Life in the Aztec World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0195330830.

- K. Mills, W. B. Taylor & S. L. Graham (eds), Colonial Latin America: A Documentary History, 'The Aztec Stone of the Five Eras', p. 23

- Solís, Felipe (2000). "La Piedra del Sol". Arqueología Mexicana. VII (41): 32–39.

- Antonio de León y Gama: Descripción histórica y cronológica de las dos piedras León y Gama

- Townsend, Casey (1979). State and Cosmos in the Art of Tenochtitlan. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks.

- K. Mills, W. B. Taylor & S. L. Graham (eds), Colonial Latin America: A Documentary History, 'The Aztec Stone of the Five Eras', pp. 23, 25

- K. Mills, W. B. Taylor & S. L. Graham (eds), Colonial Latin America: A Documentary History, 'The Aztec Stone of the Five Eras', pp. 25–6

- Townsend, Richard Fraser (1997-01-01). State and cosmos in the art of Tenochtitlan. Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. ISBN 9780884020837. OCLC 912811300.

- Smith, Michael (2002). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631230168.

- Umberger, Emily (1996). "Art and Imperial Strategy in Tenochtitlan". In Hodge, Mary G. (ed.). Aztec Imperial Strategies. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 85–106. ISBN 978-0884022114.

- Latorre, Guisela (December 2008). Walls of Empowerment: Chicana/O Indigenist Murals of California. ISBN 9780292793934.

- Austin, Alfredo Lopéz; Luján, Leonardo López (2008). "Aztec Human Sacrifice". In Brumfiel, Elizabeth M.; Feinman, Gary M. (eds.). The Aztec World. New York: Abrams. pp. 137–152. ISBN 978-0810972780.

- Brumfiel, Elizabeth M.; Millhauser, John K. (2014). "Representing Tenochtitlan: Understanding Urban Life by Collecting Material Culture". Museum Anthropology. 37 (1): 6–16. doi:10.1111/muan.12046.

- Dean, Carolyn (Summer 2006). "The Trouble with (The Term) Art". Art Journal. 65 (2): 24–32. doi:10.2307/20068464. JSTOR 20068464.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (2012). "La Piedra de Tízoc y la del Antiguo Arzobispado". Escultura monumental mexica. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 9786071609328.

- Matos Moctezuma, The Aztec Calendar and other Solar Monuments

- Peabody Museum http://collections.peabody.yale.edu/search/Record/YPM-ANT-019231

- Art Institute of Chicago https://www.artic.edu/artworks/75644/coronation-stone-of-motecuhzoma-ii-stone-of-the-five-suns

- "Throne of Montezuma".

- "Moctezuma's Throne".

Sources

- Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel. Handbook To: Life in the Aztec World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. "Huitzilopotchli's Conquest: Aztec Ideology in the Archaeological Record." Cambridge Archaeological Journal 8, no. 1 (1998): 3–13.

- Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. and John K. Millhauser. "Representing Tenochtitlan: Understanding Urban Life by Collecting Material Culture." Museum Anthropology 37, no. 1 (2014): 6–16.

- Carrasco, David L. The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Dean, Carolyn. "The Trouble with (The Term) Art." Art Journal 65, no. 2 (Summer 2006): 24–32.

- Fauvet-Berthelot, Marie-France and Leonardo López Luján. "La Piedra del Sol ¿en París?". Arqueología Mexicana 18, no. 107 (2011): 16-21.

- Hassig, Ross. "Reinterpreting Aztec Perspectives." In Time, History, and Belief in Aztec and Colonial Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001.

- Klein, Cecelia F. "The Identity of the Central Deity on the Aztec Calendar." The Art Bulletin 58, no. 1 (March 1972): 1–12.

- León y Gama, Antonio de. Descripción histórica y cronológica de las dos piedras: que con ocasión del empedrado que se está formando en la plaza Principal de México, se hallaron en ella el año de 1790. Impr. de F. de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, 1792. An expanded edition, with descriptions of additional sculptures (like the Stone of Tizoc), edited by Carlos Maria Bustamante, published in 1832. There have been a couple of facsimile editions, published in the 1980s and 1990s.

- López Austin, Alfredo and Leonardo López Luján. “Aztec Human Sacrifice.” In The Aztec World, edited by Elizabeth M Brumfiel and Gary M. Feinman, 137–152. New York: Abrams, 2008.

- López Luján, Leonardo. ""El adiós y triste queja del Gran Calendario Azteca": el incesante peregrinar de la Piedra del Sol." Arqueología Mexicana 16, no. 91 (2008): 78-83.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo, and Felipe Solís. The Aztec Calendar and other Solar Monuments. Grupo Azabache, Mexico. 2004.

- Mills, K., W. B. Taylor & S. L. Graham (eds.), Colonial Latin America: A Documentary History, 'The Aztec Stone of the Five Eras'

- Smith, Michael E. The Aztecs. 2nd ed. Hoboken: WIley-Blackwell, 2002.

- Solis, Felipe. "La Piedra del Sol." Arqueologia Mexicana 7(41):32–39. Enero – Febrero 2000.

- Umberger, Emily. "The Structure of Aztec History." Archaeoastronomy IV, no. 4 (Oct–Dec 1981): 10–18.

- Umberger, Emily. "Art and Imperial Strategy in Tenochtitlan." In Azter Imperial Strategies, edited by Mary G. Hodge, 85–106. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 1996.

- Villela, Khristaan D., and Mary Ellen Miller (eds.). The Aztec Calendar Stone. Getty Publications, Los Angeles. 2010. (This is an anthology of significant sources about the Sun Stone, from its discovery to the present day, many presented in English for the first time.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aztec sun stone. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |