Siege of Thessalonica (617)

The Siege of Thessalonica in 617 or 618 was an unsuccessful siege of the city of Thessalonica, the major Byzantine stronghold in the region, by the Avars and the Slavic tribes (Sclaveni) who had settled in the city's vicinity. The attack was the last and best-organized attempt by the Avars to take the city. It lasted 33 days and involved the use of siege engines, but in the end failed. The main source for these events are the Miracles of Saint Demetrius, named after Thessalonica's patron saint, Saint Demetrius.

Background

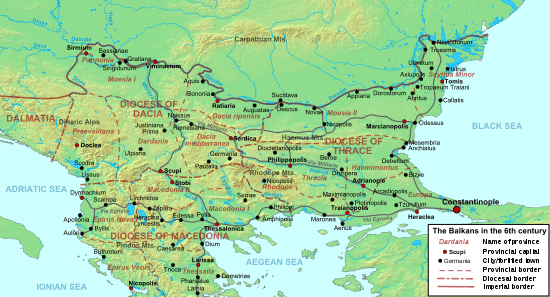

In the last third of the 6th century, the Byzantine Balkans were threatened by large-scale raids of the Avars, based in the Pannonian Plain, and their Slavic allies, based north of the Danube, which marked the northwestern border of the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines, focusing on their eastern border, where they faced the Sassanid Persians in a protracted war, were unable to maintain an effective defence of the region: following the fall of Sirmium in 582 and of Singidunum in the year after, the Balkans lay open to Avar raiding.[1][2] Along with the Avars, the breach in the Danube limes allowed the Slavic tribes to raid further and further south into as far south as Greece, and to begin a gradual process of settlement in these areas, the extent, chronology and other details of which are much debated.[3] During these raids, probably in 586 (although 597 is a possible alternative date), Thessalonica, the most important city throughout the Balkans except the capital Constantinople itself, was besieged by the Avars and their Slavic auxiliaries for seven days, as described in the Miracles of Saint Demetrius, a collection of miracles attributed to the city's patron saint in two books, one written ca. 610 and the other around 680.[4][5]

After peace had been settled with the Persians in the East in 591, Byzantine emperor Maurice and his generals were able to drive back the Slavs and the Avars in a series of campaigns. However, Maurice's victories ultimately failed to restore the stability of the Danube limes due to the rebellion of the Danube army in 602, which led to Maurice's deposition and murder, and the accession of the usurper Phocas.[6][7] The renewal of war with Persia meant the rapid and complete collapse of the Danube frontier in the first decades of the 7th century, as imperial forces were withdrawn to the East. Phocas and his successor Heraclius bought off peace with the Avars through annual tributes, but the Slavs once again had a free hand in raiding the Balkans, and in 604, a force of 5,000 men suddenly attacked Thessalonica at night, but failed to scale the city walls.[8][9]

Siege and aftermath

It was not until the 610s, however, that the Avars and the Slavs renewed their offensive; a number of cities seem to have fallen and/or been abandoned at this time, with many refugees streaming south.[10] In 615, a coalition of Slavic tribes under chief Chatzon, apparently independent of the Avars, attacked Thessalonica, but failed.[11][12] Following this failure, the Slavs turned to the Avars, and sent emissaries to the khagan, enticing him with promises of great riches to be found in the city, and the fact that Thessalonica was the ultimate refuge for the Byzantines "from the Danubian regions, Pannonia, Dacia, Dardania and the other provinces and cities" fleeing the Avar and Slavic raids.[13][12]

The Avar attack materialized in 617 (or possibly 618), as they needed time to mobilize their various subject tribes. According to the narrative of the Miracles of Saint Demetrius, the attack was unexpected: the Avars first sent scouts who captured anyone they caught outside the city walls. The khagan with the bulk of his forces, including heavy siege engines, catapults, battering rams, and siege towers, arrived a few days later. Emperor Heraclius, surprised by the Avar attack and heavily committed against the Persians, was unable to send any help; except for a few supply ships that arrived in time, the city was forced to rely on its own forces.[14][15] Although the technical sophistication of the besiegers was unprecedented, they were apparently unable to make full use of it due to inexperience: a siege tower collapsed and killed its crew, while the battering rams proved ineffective against the city walls. The siege was far better organized than the previous attempts, however, and dragged on for 33 days. In the end, the khagan reached a negotiated settlement with the Thessalonians: he departed in exchange for gold, but not before burning the churches of the surrounding countryside. The Slavs, on the other hand, sold their captives to the Thessalonians. For a generation, until the great Slavic siege of ca. 676–678, Thessalonica would remain in peace with its Slavic neighbours.[14][16]

References

- Christophilopoulou (2006), pp. 13–14

- Pohl (1988), pp. 70–89

- cf. Pohl (1988), pp. 94–128

- Christophilopoulou (2006), pp. 15, 22

- Pohl (1988), pp. 101–107

- Christophilopoulou (2006), pp. 14–17

- Pohl (1988), pp. 128–162

- Christophilopoulou (2006), pp. 19, 24–25

- Pohl (1988), pp. 237–241

- Pohl (1988), pp. 241–242

- Christophilopoulou (2006), p. 25

- Pohl (1988), p. 241

- Christophilopoulou (2006), pp. 25–26

- Christophilopoulou (2006), p. 26

- Pohl (1988), p. 242

- Pohl (1988), pp. 242–243

Sources

- Christophilopoulou, Aikaterini (2006). "Βυζαντινή Μακεδονία. Σχεδίασμα για την εποχή από τα τέλη του Στ' μέχρι τα μέσα του Θ' αιώνος". Βυζαντινή Αυτοκρατορία, Νεώτερος Ελληνισμός, Τόμος Γ' (in Greek). Athens: Herodotos. pp. 9–68. ISBN 960-8256-55-0.

- Pohl, Walter (1988). Die Awaren. Ein Steppenvolk in Mitteleuropa 567–822 n. Chr (in German). Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck. ISBN 3-406-33330-3.