Auraicept na n-Éces

Auraicept na n-Éces ([arakʲept na neːgʲes], "the scholars' [éices] primer [airaiccecht]"; in the modern Gaelic languages: Irish: Aiceacht na nÉigeas, Scottish Gaelic: Uraiceachd nan Éigeas) was historically thought to be a 7th-century work of Irish grammarians, written by a scholar named Longarad. The core of the text may date to the mid-7th century, but much material was added between that date and the production of the earliest surviving copy in the 12th century.

If it indeed dates to the 7th century, the text is the first instance of a defence of vernaculars, defending the spoken Irish language over Latin, predating Dante's De vulgari eloquentia by 600 years and Chernorizets Hrabar's O pismeneh by 200 years.

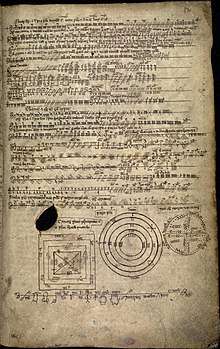

Manuscripts

- TCD H 2.18. (Book of Leinster), ca. 1160

- TCD H 2.16. (YBL), 14th century

- RIA 23 P 12 (Book of Ballymote), foll. 169r–180r, ca. 1390

- BM E.g. 88, 1564

Contents

The Auraicept consists of four books,

- I: The Book of Fenius Farsaidh

- II: The Book of Amergin

- III: The Book of Fercheirtne Filidh

- IV: The Book of Cennfaeladh

The author argues from a comparison of Gaelic grammar with the materials used in the constructions of the Tower of Babel:

Others affirm that in the tower there were only nine materials and that these were clay and water, wool and blood, wood and lime, pitch, linen, and bitumen ... These represent noun, pronoun, verb, adverb, participle, conjunction, preposition, interjection

(note the discrepancy of nine materials vs. eight parts of speech). As pointed out by Eco (1993), Gaelic was thus argued to be the only instance of a language that overcame the confusion of tongues, being the first language that was created after the fall of the tower by the seventy-two wise men of the school of Fenius, choosing all that was best in each language to implement in Irish. Calder notes (p. xxxii) that the poetic list of the "72 races" was taken from a poem by Luccreth moccu Chiara.

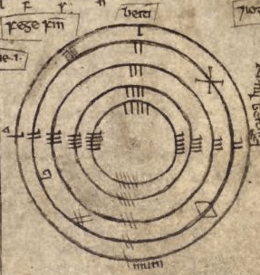

Ogham

The Auraicept is one of the three main sources of the manuscript tradition about Ogham, the others being In Lebor Ogaim and De dúilib feda na forfed. A copy of In Lebor Ogaim immediately precedes the Auraincept in the Book of Ballymote, but instead of the Bríatharogam Con Culainn given in other copies, there follows a variety of other "secret" modes of ogham. The Younger Futhark are also included, as ogam lochlannach "ogham of the Norsemen".

Similar to the argument of the precedence of the Gaelic language, the Auraicept claims that Fenius Farsaidh discovered four alphabets, the Hebrew, Greek and Latin ones, and finally the ogham, and that the ogham is the most perfected because it was discovered last. The text is the origin of the tradition that the ogham letters were named after trees, but it gives as an alternative possibility that the letters are named for the 25 members of Fenius' school.

In the translation of Calder (1917),

This is their number: five Oghmic groups, i.e., five men for each group, and one up to five for each of them, that their signs may be distinguished. These are their signs: right of stem, left of stem, athwart of stem, through stem, about stem. Thus is a tree climbed, to wit, treading on the root of the tree first with thy right hand first and thy left hand after. Then with the stem, and against it and through it and about it. (Lines 947-951)

In the translation of McManus:

This is their number: there are five groups of ogham and each group has five letters and each of them has from one to five scores and their orientations distinguish them. Their orientations are: right of the stemline, left of the stemline, across the stemline, through the stemline, around the stemline. Ogham is climbed as a tree is climbed

References

- James Acken, Structure and Interpretation in the Auraicept na nÉces. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller e.K., 2008. ISBN 978-3-639-02030-4

- George Calder, Auraicept na n-éces, The Scholars Primer, being the texts of the ogham tract from the Book of Ballymote and the Yellow Book of Lecan, and the text of the Trefhocul from the Book of Leinster, ... , John Grant, Edinburgh 1917 (1995 repr.)

- Anders Ahlqvist, The Early Irish Linguist (Auraicept na nÉces), Helsinki 1982

- R. Thurneysen, "Auraicept na n-éces", in: ZCP 17, 1928, pp. 277–303.

- Erich Poppe, "Die mittelalterliche irische Abhandlung Auraicept na nÉces und ihr geistesgeschichtlicher Standort", in: Theorie und Rekonstruktion, edd. von Klaus D. Dutz & Hans-J. Niederehe. Münster: Nodus, 1996, 55-74.

- Erich Poppe, "Natural and Artificial Gender in Auraicept na nÉces", in: SH 29, 1995–97, 195-203.

- Erich Poppe, "Latinate Terminology in Auraicept na nÉces", in: History of Linguistics 1996. Vol. 1: Traditions in Linguistics Worldwide. Eds. David Cram, Andrew Linn, Elke Nowak. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins. 1999, 191-201.

- Erich Poppe, "The Latin Quotations in Auraicept na nÉces: Microtexts and their Transmission", in: Ireland and Europe in the Early Middle Ages. Texts and Transmission, edd. Próinséas Ní Chatháin & Michael Richter. Dublin: Four Courts. 2002, 296-312.

- Umberto Eco, The search for the perfect language (1993, book translated in English 1995).

- — Serendipities : Language and Lunacy (1998).

- Damian McManus, A Guide to Ogam, An Sagart, 1997

Editions

- Calder, George, ed. (1995) [1917]. Auraicept na n-Éces : the scholars' primer ; being the texts of the Ogham tract from the Book of Ballymote and the Yellow Book of Lecan, and the text of the Trefhocul from the Book of Leinster (Repr. [d. Ausg.] Edinburgh 1917. ed.). Blackrock: Four Courts Press. ISBN 1-85182-181-3. Archived from the original on 2006-09-04. Retrieved 2005-11-01.