Book of Leinster

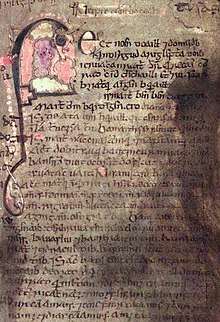

The Book of Leinster (Irish Lebor Laignech [ˈl͈ʲevor laignex]), is a medieval Irish manuscript compiled c. 1160 and now kept in Trinity College, Dublin, under the shelfmark MS H 2.18 (cat. 1339). It was formerly known as the Lebor na Nuachongbála "Book of Nuachongbáil", a monastic site known today as Oughaval.

| Book of Leinster | |

|---|---|

| Dublin, TCD, MS 1339 (olim MS H 2.18) | |

f. 53 | |

| Also known as | Lebor Laignech (Modern Irish Leabhar Laighneach); Lebor na Nuachongbála |

| Type | miscellany |

| Date | 12th century, second half |

| Place of origin | Terryglass (Co. Tipperary) and possibly Oughaval or Clonenagh (Co. Laois) |

| Scribe(s) | Áed Ua Crimthainn |

| Size | c. 13″ × 9″; 187 leaves |

| Condition | 45 leaves lost, according to manuscript note. |

| Previously kept | by the Ó Mhorda and Sir James Ware |

Some fragments of the book, such as the Martyrology of Tallaght, are now in the collection of University College, Dublin.[1]

Date and provenance

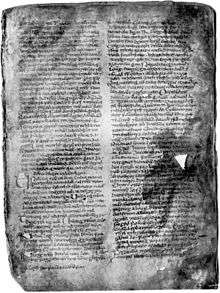

The manuscript is a composite work and more than one hand appears to have been responsible for its production. The principal compiler and scribe was probably Áed Ua Crimthainn,[2][3] who was abbot of the monastery of Tír-Dá-Glas on the Shannon, now Terryglass (County Tipperary), and the last abbot of that house for whom we have any record.[3] Internal evidence from the manuscript itself bears witness to Áed's involvement. His signature can be read on f. 32r (p. 313): Aed mac meic Crimthaind ro scrib in leborso 7 ra thinoil a llebraib imdaib ("Áed Húa Crimthaind wrote this book and collected it from many books"). In a letter copied by a later hand into a bottom margin (p. 288), the bishop of Kildare, Finn mac Gormáin (d. 1160), addresses him as a man of learning (fer léiginn) of the high-king of Leth Moga, the coarb (comarbu lit. 'successor') of Colum mac Crimthainn, and the chief scholar (prímsenchaid) of Leinster. An alternative theory was that by Eugene O'Curry, who suggested that Finn mac Gormáin transcribed or compiled the Book of Leinster for Áed.[3]

The manuscript was produced by Aéd and some of his pupils over a long period between 1151 and 1224.[3] From annals recorded in the manuscript we can say it was written between 1151 and 1201, with the bulk of the work probably complete in the 1160s. As Terryglass was burnt down in 1164, the manuscript must have been finalised in another scriptorium.[3] Suggested locations include Stradbally (Co. Loais) and Clonenagh (Co. Laois), the home of Uí Chrimthainn (see below).[3]

Eugene O'Curry suggested that the manuscript may have been commissioned by Diarmait Mac Murchada (d. 1171), king of Leinster, who had a stronghold (dún) in Dún Másc, near Oughaval (An Nuachongbáil). Dún Másc passed from Diarmait Mac Murchada to Strongbow, from Strongbow to his daughter Isabel, from Isabel to the Marshal Earls of Pembroke and from there, down several generations through their line. When Meiler fitz Henry established an Augustinian priory in Co. Laois, Oughaval was included in the lands granted to the priory.

History

Nothing certain is known of the manuscript's whereabouts in the next century or so after its completion, but in the 14th century, it came to light at Oughaval. It may have been kept in the vicarage in the intervening years.

The Book of Leinster owes its present name to John O'Donovan (d. 1861), who coined it on account of the strong associations of its textual contents with the province of Leinster, and to Robert Atkinson, who adopted it when he published the lithographic facsimile edition.[3]

However, it is now commonly accepted that the manuscript was originally known as the Lebor na Nuachongbála, that is the "Book of Noghoval", now Oughaval (Co. Laois), near Stradbally. This was established by R.I. Best, who observed that several short passages from the Book of Leinster are cited in an early 17th-century manuscript written by Sir James Ware (d. 1666), found today under the shelfmark London, British Library, Add. MS 4821. These extracts are attributed to the "Book of Noghoval" and were written at a time when Ware stayed at Ballina (Ballyna, Co. Kildare), enjoying the hospitality of Rory O'Moore. His family, the O'Moores (Ó Mhorda), had been lords of Noghoval since the early 15th century if not earlier, and it was probably with their help that he obtained access to the manuscript. The case for identification with the manuscript now known as the Book of Leinster is suggested by the connection of Rory's family to the Uí Chrimthainn, coarbs of Terryglass: his grandfather had a mortgage on Clonenagh, the home of Uí Chrimthainn.[4]

Best's suggestion is corroborated by evidence from Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS B. iv. 2, also of the early 17th century. As Rudolf Thurneysen noted, the scribe copied several texts from the Book of Leinster, identifying his source as the "Leabhar na h-Uachongbála", presumably for Leabhar na Nuachongbála ("Book of Noughaval").[5] Third, in the 14th century, the Book of Leinster was located at Stradbally (Co. Laois), the place of a monastery known originally as Nuachongbáil "of the new settlement" (Noughaval) and later as Oughaval.[6]

Contents

The manuscript has 187 leaves, each approximately 13" by 9" (33 cm by 23 cm). A note in the manuscript suggests as many as 45 leaves have been lost. The book, a wide-ranging compilation, is one of the most important sources of medieval Irish literature, genealogy and mythology, containing, among many others, texts such as Lebor Gabála Érenn (the Book of Invasions), the most complete version of Táin Bó Cuailnge (the Cattle Raid of Cooley), the Metrical Dindshenchas and an Irish translation/adaptation of the De excidio Troiae Historia, and before its separation from the main volume, the Martyrology of Tallaght.

A diplomatic edition was published by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies in six volumes over a period of 29 years.

Notes

- Ms A3 at www.ucd.ie

- Best, The Book of Leinster, vol 1, p. xv.

- Hellmuth, "Lebor Laignech", pp. 1125-6.

- Best, The Book of Leinster, vol 1, pp. xi–xvii.

- Thurneysen, Die irische Helden- und Königsage bis zum 17. Jahrhundert, p. 34.

- Best, Book of Leinster, vol. 1, p. xi-xv

References

Editions

- Atkinson, Robert. The Book of Leinster, sometimes called the Book of Glendalough. Dublin, 1880. 1–374. Facsimile edition.

- Book of Leinster, ed. R.I. Best; Osborn Bergin; M.A. O'Brien; Anne O'Sullivan (1954–83). The Book of Leinster, formerly Lebar na Núachongbála. 6 vols. Dublin: DIAS. Available from CELT: vols. 1 (pp. 1–260), 2 (pp. 400–70), 3 (pp. 471–638, 663), 4 (pp. 761–81 and 785–841), 5 (pp. 1119–92 and 1202–1325) . Diplomatic edition.

Secondary sources

- Hellmuth, Petra S. (2006). "Lebor Laignech". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Denver, and Oxford: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1125–6.

- Ní Bhrolcháin, Muireann (2005). "Leinster, Book of". In Seán Duffy (ed.). Medieval Ireland. An Encyclopedia. New York and Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 272–4.

- Ó Concheanainn, Tomás (1984). "LL and the Date of the Reviser of LU". Éigse. 20: 212–25.

- O'Sullivan, William (1966). "Notes on the Scripts and Make-Up of the Book of Leinster". Celtica. 7: 1–31.

External links

- Contents of the Book of Leinster

- Translations into English for much of the Book of Leinster

- Irish text: volumes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 & 6 at CELT