Azcapotzalco

Azcapotzalco (Classical Nahuatl: Āzcapōtzalco Nahuatl pronunciation: [aːskapoːˈt͡saɬko] (![]()

![]()

Azcapotzalco | |

|---|---|

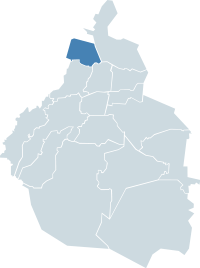

Azcapotzalco within the Federal District | |

| Coordinates: 19°28′58″N 99°11′00″W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| Federal entity | Mexico City |

| Established | 1928 |

| Named for | Ancient Tepanec city |

| Seat | Av. Castilla Oriente s/n esq. 22 de Febrero |

| Government | |

| • Jefe delegacional | Sergio Palacios Trejo (PRD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 33.6 km2 (13.0 sq mi) |

| Population 2010[2] | |

| • Total | 414,711 |

| • Density | 12,000/km2 (32,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central Daylight Time) |

| Postal codes | 02000-02990 |

| Area code(s) | 55 |

| Website | www.azcapotzalco.gob.mx |

Geography and environment

The municipality of Azcapotzalco is in the Valley of Mexico with its eastern half on the lakebed of the former Lake Texcoco and the west on more solid ground. The historic center is on the former shoreline of this lake.[4][5] The average altitude is 2240 meters above sea level.[6] Politically, the municipality extends over 34.5km2 in the northwest of the Federal District of Mexico City, bordering the municipality of Gustavo A. Madero, Cuauhtémoc, Miguel Hidalgo along with the municipalities of Tlalnepantla de Baz, and Naucalpan in the State of Mexico.[6]

It has a semi moist temperate climate with an average temperature of 15C.[6]

| Azcapotzalco | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As the municipality is 100% urbanized, there are no ecological reserves. It is divided into 2,723 city blocks.[5][6] There are 54 parks which have no wild vegetation but rather planted species such as willow, cedar and pine trees. These parks cover 100.51 hectares, which is 2.9% of the entire municipality. The most important of these are the Parque Tezozómoc and Alameda Norte, which together account for 52.4 hectares.[5][7]

Parque Tezozomoc was inaugurated in 1982 designed as a scaled replica of the Valley of Basin of Mexico in the pre-Hispanic era.[5] The Alamedia Norte park is next to the Ferrería station. It has a pond which was used as an ice rink and playing field but was rehabilitated in the 2000s.[8]

Other important green areas include community squares such as Plaza Hidalgo, sports centers, college campuses, especially that of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, community parks and cemeteries.

Sports facilities cover about 67 hectares of the municipality with 70 fields and sports centers open to the public. These include the Deportivo Renovacion Nacional, Deportivo Reynosa, Centro Deportivo Ferrocarrilero and the Unidad Deportiva Benito Juarez.[5] Deportivo Reynosa used to host one of Mexico City's temporary “artificial beaches” consisting of pools and a sand area, which were constructed by the city government as a service to the poor.[9] The municipality has cemeteries which are counted as green spaces, especially San Isidro because of its large size.[5]

There is little surface water with the exception of the Río de los Remedios which is primarily used for drainage of wastewater.[6] The lowering of water tables in the valley has led to large cracks developing in areas of the municipality which has caused damage to infrastructure.[5] The municipality is flat with inclines of between zero and five percent with no prominent elevations.[5][6] Because of its flatness, flooding is a problem in heavy rain, especially in areas such as Santiago Ahuizotla, Nueva Santa María, San Pedro Xalpa and Pro Hogar.[5]

Sixty five percent of the municipality is occupied by about 500 industries which use toxic substances. There are hundreds of km of underground gas lines. Nine communities have been classified as high risk because they are surrounded by industries.[10] There are 250 chemical producers mostly concentrated in Colonia Industrial Vallejo which make ethanol, cyanide compounds, phosphates, organic solvents and more.[5]

Air pollution is a significant problem in the municipality as it is in the rest of Mexico City. Most comes from vehicular traffic and industry; it includes ozone, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide as well as suspended particles. Noise pollution is caused by industry and truck traffic.[5] Although the municipality has no surface water, water pollution in its drainage is a problem from residential areas and industry. Industry contamination is mostly in the form of poor water use and the dumping of prime materials often from cleaning and includes organic matter, grease, soaps and detergents, dyes, solvents and more. Solid waste production is a problem from industrial and residential sources. The amount of waste produced in the municipality has grown almost seven-fold since the 1980s at a current rate of 571 tons per day.[5]

Due to the proximity of the old 18 de Marzo refinery (which was part of the municipality), there are many underground pipes some of which are still in use. Even more are associated with another nearby but active refinery Terminal de Almacenamiento y Distribución de Destiados de Pemex-Refinación. Most pipelines are found under Avenida Tezozomoc, 5 de Mayo, Salónica, Eje 3 Norte, Ferrocarril Central and Encarnación Ortiz.[5]

Communities

Originally the town of Azcapotzalco consisted of neighborhoods from the pre-Hispanic period. Many of these neighborhoods exist to this day, called colonias, barrios or pueblos. A number of them maintain individual cultural traits despite being fully engulfed by the urban sprawl of Mexico City. These include San Juan Tlihuaca, San Pedro Xalpa, San Bartolo Cahualtongo, Santiago Ahuizotla, San Miguel Amantla, Santa Inés, Santo Domingo, San Francisco Tetecala, San Marcos, Los Reyes and Santa María Malinalco.[5] Today, the municipality has 61 colonias, 15 pueblos and 11 barrios.[7] In 1986, INAH designated the center of Azcapotzalco as a historical monument.[11]

In 2011, the historic center was designated as a "Barrio Mágico".[12]

The most important community remains the former town of Azcapotzalco, also called the historic center, marked by Plaza Hidalgo. This square consists of fenced stone paths surrounding gardens. Its two main focal points are a statue of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla facing Avenida Azcapotzalco and a six-sided kiosk in the center.[13] On Saturdays, chess players convene to play during the afternoon.[14] Café Alameda is on Plaza Hidalgo — a café and bar with a rock and roll theme. It has images of Jim Morrison, Freddie Mercury, Elvis Presley, and John Lennon lining its walls. At night on weekends, it hosts live bands which attracts youths from the area.[14] The Historic Archive of Azcapotzalco is on the south side of Plaza Hidalgo. It contains a mural painted by Antonio Padilla Pérez titled Origen y Trascendencia del Pueblo Tepaneca. The building contains archeological pieces.[13]

Across the street from the plaza are the parish church and the former municipal hall. The parish and former monastery of San Felipe and Santiago Apóstoles dates from 1565.[13] It has the largest atrium in Mexico City, surrounded by a thick wall with inverted arches.[13][15] The main church has a large Baroque portal which contains the main door topped by a choir window. To the side there is a slender bell tower with pilasters on it four sides. Under the tower, there is an image of a red ant. A local legend says that when the ant climbs the bell tower, the world will end.[13][15] To the right of the portal are three arches that front the former Dominican monastery. The interior of the church has a Baroque gilded altarpiece with Salomonic columns which contains images of the Virgin Mary. The main altar is Neoclassical. To the side there is a chapel called the Capilla del Rosario from 1720 with Baroque and Churrigueresque altars. The former cloisters has remains of its former mural work.[13]

Next to the parish and taking over some of its former atrium space is the Casa de Cultura cultural center. The building was constructed in 1891 originally as the municipal hall for Azcapotzalco.[13][16] It has a sandstone portal with a balcony on the upper level featuring a double arch and an ironwork railing from 1894.[13] The building has three exhibition halls on the lower level. The upper level is dedicated to the Sala Tezozomoc hall, larger than the lower halls combined. The garden areas have rosebushes and orange trees. These areas host art exhibits, workshops, classes and other cultural events.[16] The center has a mural called La herencia tepaneca en ul umbral del tercer milenio by Arturo García Bustos, a student of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.[15] In 1986, the building was named a historic monument by INAH and converted into its current use in 1991 on its 100th anniversary.[16]

The main street in the historic center is Avenida Azcapotzalco, which is home to long-established businesses. One of these is the Nevería y Cafetería El Nevado, which has a 1950s rock and roll atmosphere, uniformed waitresses and mid 20th-century furnishings.[13][14] There are cantinas such as El Dux de Venicia (over 100 years old) with its original furniture and La Luna established in 1918 and noted for its “torta” sandwiches.[13][15]

The Principe Tlaltecatzin Archeological Museum is a private institution founded by Octavio Romera that focuses on pre-Hispanic pieces related to the Azcapotzalco area. It is the result of a lifelong exploration and study of artifacts he found since he was a child. He educated himself and is considered an expert in the pre-Hispanic history and archeology of the area.[17]

The oldest library of the municipality, Biblioteca Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, has murals by Juan O’Gorman.[15]

In addition to the historic center there are other important communities, many of which maintain old traditions. The Barrio de San Miguel Amantla is near the former 18 de Marzo refinery. It is one of the oldest in the municipality with one of the oldest churches. In the Mesoamerican period, it was noted for its plumería or the making of objects with feathers.[6] The oldest standing church is in San Miguel Amantla which had fallen into ruins but was rebuilt using the original blocks.[6] Barrio de San Luis is one of over 20 which date from the Mesoamerican period. It is noted for its church and its barbacoa.[15] The Barrio de Santa Apolonia Tezcolco was the site of the Tezozomoc's treasury. The Barrio de San Juan Tlilhuaca is the largest neighborhood in the municipality and contains the largest church. This church is famous for its passion play for Holy Week and is surrounded by old cypress trees said to have been planted as tribute to Moctezuma.[6]

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, areas in the municipality became the site of country homes for the wealthy of Mexico City. Today a number of chalet and English style homes with pitched roofs, towers, porches and gardens can be seen especially in the Clavería neighborhood. This neighborhood was as exclusive as Colonia Juárez and Colonia Condesa at that time.[13][15] Of the housing developments construction in the latter 20th century, the most important is the Unidad Habitational El Rosario. This apartment complex has 170 buildings, with 7,606 apartments housing over 50,500 residents. It is the largest of its kind in Latin America.[6][18]

Socioeconomics

The municipality as it is found today is a product of the growth of the Mexico City area in the 20th century, especially since the 1970s. The population rose from 534,554 in 1970 to a peak of 601,524 in 1980. The population began to drop to 474,688 in 1990 and 441,008 in 2000. In addition to loss of employment, reasons for the population loss include the 1985 earthquake and the high cost of living space, especially compared to neighboring state of Mexico.[5] Problems in the municipality include uncontrolled street vending, historic buildings abandoned or used as commercial space, lack of maintenance of parks, and heavy traffic. This is particularly problematic in the historic center.[11]

21.7% of the territory is used for industry, 15.5% for storage, 42.12% for housing, open spaces 2.9%, and mixed use 17.78%. Overall, the level of socioeconomic marginalization is low compared to the other municipalities, coming in 12th of 16 in 2005. However, areas of the municipality have very high levels of socioeconomic socialization including Barrio Coltongo, Nueva España, Pasteros, Porvenir, Barrio de San Andrés, Pueblo de San Andrés, San Francisco Xocotitla, San Martín Xochinahuac, San Miguel Amantla, San Rafael, San Sebastián, Santa Barbara, Santiago Ahuizotla. Santo Tomas, Tierra Nueva and the Unidad Habitacional Cruz Roja Tepantongo. Sixty nine percent of the communities are considered to be of medium to high marginalization with 10 communities considered to be of low socioeconomic marginalization: Ampliación San Pedro Xalpa, Ferrería, Industrial Vallejo, Las Salinas and Santa Cruz de las Salinas.[5]

About 80% of the municipality's population is working age. Just over 53% of the population is employed. The rest are mostly students, homemakers and retired. Almost all employed persons work in industry, commerce and services. Industry employs just over 21%.[5]

The most important sector to the municipality's economy is industry despite its decline since the very late 20th century. Industry accounts for about 72% of the municipality's production with commerce and services accounting for the rest. The industrial zone in Azcapotzalco is one of the most important in the Federal District. This zone is centered on Colonia Industrial Vallejo extending into San Salvador Xochimanca, Coltongo, Santo Tomas, San Martin Xochinahuac, Santa Ines, Santo Domingo, Ampliacion Petrolera, Industrial San Antonio, San Miguel Amantla, San Pablo Xalpa and San Juan Tlihuaca. Much of the industry has slowed or halted due to competition abroad which can make them cheaper. This has led to efforts to reorient the municipality's economy because of the high rates of unemployment and migration out of the area.[5] About sixty percent of the Federal District's heavy industry is in the municipality.[10] The municipality accounts for about 40% of the Federal District's industrial zoning and provides over 15% of industrial employment.[5]

Housing in the municipality is varied. Most residential buildings (45%) are two or three levels, as a single house with two or three families. Apartment buildings average about five floors. Since the 1970s, there has been construction of extremely large apartment complexes such as the Unidad Habitacional El Rosario. There are 340 “vecindades,” irregular structures generally made with construction and industrial waste, which can be found mostly in Colonia Pro-Hogar, Colonia Ampliacion San Pedro Xalpa, Coltongo and Liberación. Azcapotzalco is one of the city most crowded municipalities, mostly due to the large apartment complexes, but the decline in population has alleviated this somewhat.[5]

Azcapotzalco is ranked 9th of 16 municipalities in reported crime which is often associated with gangs and the use of drugs.[19] In the municipality there are 70 communities considered to have high drug use accounting for about 45% of the total population. These include La Raza, El Rosario, Prohogar, Industrial Vallejo, La Preciosa, San Pedro Xalpa and ObreraMundial.[20] There are crime gangs identified by police such as Los Pepes, Los Negros and Los Maquedas.[18] The most frequent violent crimes include muggings, car theft and robbery of businesses — much of which is related to the socioeconomic problems of the area.[19]

The municipality provides services to ease socioeconomic problems such as health, education, recreation and other programs.[5] It runs 20 traditional fixed markets and has offered vendors courses in marketing.[21] In 2008 the city sponsored an entrepreneurship program with the Instituto Politécinco Nacional and the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana to help deal with the loss of employment.[22] Starting in 2008, the municipality has offered free wedding ceremonies and certificates to encourage couples to formally legalize their unions. The wedding ceremonies involve hundreds of couples who are married at the same time.[23]

History

The name is derived from Nahuatl and means “ant hill” with the municipality Aztec glyph depicting a red ant surrounded by corn. It comes from a legend that says that after the creation of the Fifth Sun, the god Quetzalcoatl was tasked with recreating man. To do this, he needed to enter the realm of the dead, Mictlan, to recover the bones of men from the Fourth Sun. Ants helped Quetzalcoatl to find the realm of the dead and bring the bones up as well as grains of corn. Another version of the legend relates to the discovery of corn by observing that ants had put grains underground and corn plants grew there.[4]

The very early history of the area follows that of the rest of the Valley of Mexico.[6] About 7,000 years ago, hunter/gatherers arrived to the valley attracted by the vegetation and large game such as mammoths. Fossilized mammoth, bison and other bones were found when Line 6 of the Metro was constructed. When the large game died out, the inhabitants of the valley turned to agriculture, forming permanent villages sometime between 5000 and 2000 BCE. Plants were domesticated — the most important of which were corn, squash, chili peppers, avocados and beans.[4]

Pottery and villages were founded all over the Valley of Mexico from 2200 BCE to 1200 BCE, supported by agriculture with some hunting and fishing. From 1200 to 700BCE the most important villages were in the south of the valley.[4] Around 200 BCE, the Teotihuacan civilization arose and the Azcapotzalco area rose in importance as well, being in the empire's political and cultural sphere. Villages that grew during this time included San Miguel Amantla, Santiago Ahuixotla and Santa Lucia which are in the south of the modern municipality.[4][24] When Teotihuacan waned in 800 CE, the Azcapotzalco area remained important as a center of that culture, becoming an important ceremonial center. When Tula rose, Toltec influence then dominated Azcapotzalco and the rest of the Valley of Mexico. Toltec influence is most evident in ceramic finds from Santiago Ahuizotla and was possibly a Toltec tribute city.[5]

When Tula fell, there were new migrations into the Valley of Mexico including Otomis, Mazahuas and Matlatzincas.[5] One of these groups was led by a chieftain called Matlacoatl in the 12th century. Legend states that he established the village of Azcapotzaltongo, which is now Villa Nicolás Romero in 1152, but its development is best documented between 1200 and 1230.[4][6] The village grew to become the Tepanec Empire in the 12th and 13th centuries with a ruling dynasty with the territory expanding over the Valley of Mexico.[5][6] Acolhuatzin was leader from 1283 to 1343. He married a daughter of Xolotl of Tenayuca and then moved the capital of the dominion to what is now the historic center of Azcapotzalco, on the edge of what was Lake Texcoco. He allowed the Mexica to settle on Tepaneca lands, founding Tenochtitlan, in exchange for tribute and military service.[4][6] The last major ruler of Azcapotzalco was Tezozomoc who ruled from 1367 to 1427. Under him the empire reached over most of the Valley of Mexico into Cuernavaca and north into Tenayuca and Atotonilco.[5][6] This made Azcapotzalco the most important city in the Valley of Mexico and archeological work related to this dominion continues to this day.

In 2012, burials and remains of buildings were found the San Simon Pochtlan neighborhood, believed to have belonged to Tepaneca traders between 1200 and 1300CE. Other settlements were found in the same area when Line 6 was constructed in 1980.[6][25]

Under the Tepanecas, conquered areas were allowed to keep their own leadership as long as they paid tribute and performed military service. In 1427, these leaders included Nezahualcoyotl of Texcoco, Izcoatl of Tenochtitlan and Totoquihuaztli of Tlacopan.[6] When Tezozomoc died, there was a power struggle for the throne which allowed these tribute-paying entities a chance to rebel, forming the Triple Alliance and defeating Azcapotzalco in 1428. The former Tepanec lands were divided among the three leaders and the city of Azcapotzalco was destroyed and turned into a slave market.[4][6][13]

With the end of the Tepanec Empire political and economic power shifted to Texcoco, Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan.[5]

The area remained ruled by the Aztec Empire until 1521, when the Aztecs fell to the Spanish when Azcapotzalco had a population of 17,000.[6] From 1528 to 1529 the Dominicans were in charge of the evangelization of the area under Fray Lorenzo de la Asunción, who built churches of over the former Tepaneca ceremonial center dedicated to the Apostles Phillip and James.[4] Despite accounts that Lorenzo de la Asuncion defended the indigenous against their Spanish overlords,[26] during the 16th century, the indigenous population of the area fell from 17,000 to about 3,000 due to mistreatment and disease.[4]

During the colonial period, the area not underwater was home to haciendas, resulting from the partition of lands among the conquistadors and their descendants.[26] In 1709, Azcapotzalco was formed by 27 communities, divided into six haciendas and nine ranches.[5] Azcapotzalco was the scene of one of the last battle of the Mexican War of Independence with the Army of the Three Guarantees under Anastasio Bustamante defeating royalist forces on August 19, 1821 shortly before Agustín de Iturbide entered Mexico City.[4][13]

At the beginning of the 19th century, the area was rural, far outside Mexico City proper, part of the State of Mexico.[4] It was organized as a municipality in 1824 with the town of Azcapotzalco serving as the seat of government for ranches and haciendas such as Ameleo, San Rafael, San Marcos, El Rosario, Pantaco, San Isidro, San Lucua, Acaletengo and Azpeitia along with communities such as Concepción, San Simón, San Martín, Santo Domingo, Los Reyes, Santa Catarina, Santa Bárbara, San Andrés, San Marcos, San Juan Mexicanos, San Juan Tlilhuaca, Xiocoyahualco, Santa Cruz del Monte, San Mateo, San Pedro, San Bartolome, San Francisco, Santa Apolonia, Santa Lucia, Santiago, San Miguel Ahuizutla, Santa Cruz Acayuca, Nextengo, San Lucas, San Bernabe, Santa Maria, San Sebastian and Santo Tomas.[5][26] When it became part of the Federal District of Mexico City in 1854, Azcapotzalco was classified as a town as part of the Guadalupe municipality but in 1899 it became the head of its own municipality.[4] The town of Azcapotzalco was still separate from Mexico City by about two leagues.[26] In the 19th century the community of San Juan Tlilhuaca was known for its warlocks.[26] By the end of the 19th century, the municipality had a population of about 11,000 with 7,500 in the seat.[5]

At that time, the area became popular with the wealthy who built country homes, especially along the Mexico-Tacuba road and near the town of Azcapotzalco. This construction was the forerunner of many of the municipality's more modern neighborhoods.[5] In the first decades of the 20th century, rail lines were constructed, including a trolley that connected the town of Azcapotzalco with Mexico City center in 1913.[13][26]

According to the 1900 census, the Federal District has an Azcapotzalco District which consisted of the municipalities of Azcapotzalco and Tacuba. These districts were eliminated in 1903, creating thirteen municipalities, of which Azcapotzalco was one. In 1928, the District was reorganized again into municipalities which the town of Azcapotzalco still heads.[4]

From the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1920, the Mexico City area began a process of rapid growth, with the modernization of infrastructure and the establishment of industry in the area. The first factories in the municipality were established in Colonia Vallejo in 1929, which lead to the industrialization of most of the area. The Refinería 18 de Marzo refinery was founded at the end of the 1930s and attracted even more industry. Today, it has been abandoned. In 1944, the federal government formally established the industrial zone of Colonia Vallejo. Around the same time the government also established a major rail station for cargo at Pantaco.[5]

The industrialization created new residential neighborhoods, mostly for the working classes. Two exception were Colonia Clavería and Nueva Santa María which remained middle class in the mid 20th century, mostly descendants of those who had built country homes.[5] In the latter 20th century, the rest of the vacant land in the municipality was built over to make the territory 100% urbanized. The urbanized area in the municipality increased from 1.8% in 1940 to 95.2% at the beginning of the 1980s. Most of this last construction in the north and west was residential areas. In the 1970s, the Azcapotzalco campus of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana was established as a major educational center for Mexico City as well as the El Rosario apartment complex, the largest of its kind in Latin America.[5]

Culture

Residents of Azcapotzalco are referred to as Chintololos.[15] There are several stories as to the origin of the term, but Azcapotzalco chronicler José Antonio Urdapilleta states that it came from a disrespectful Aztec term “tsintli- tololontic” which means excessively round buttock. Over time the pronunciation changed to the current and its disrespectful meaning disappeared.[27]

Azcapotzalco holds one of the oldest continuous annual pilgrimages to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which has been done for over 475 years. It is considered to be the first one organized by the indigenous in Mexico with records indicating the first one done in 1532, only 11 months after the report of the appearance of the Virgin Mary to Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin. The annual event is known as the Fiesta de los Naturales in which leaders from 28 communities collect money and more as offering to Guadalupe. Before the procession sets off, there is a festival with fireworks and a mass to bless the pilgrims.[28]

One legend of the area is about the “Enchanted Pool of Xancopina” a fresh water spring that existed during the pre-Hispanic era and where Moctezuma is said to have submerged much of his treasure after being defeated by the Spanish. It was where the Unidad Habitacional Cuitláhuac is now.[13] The first El Bajio restaurant was founded in Azcapotzalco and is still in operation. The chain specializes in Mexican food from the center of the country.[29]

Education

The municipality has 228 schools and other public educational facilities from preschool to university levels. These include 61 preschools, 79 primary schools, 42 middle schools, 17 high/vocational schools, six night schools, eight special education schools, four middle schools for adults, one open enrollment facility and ten infant development centers. Private education includes 71 preschools, 21 elementary schools, six middle schools, five high school level institutions and one college. However, many of the schools at the basic levels lack maintenance. The illiteracy rate is 2.34 percent, lower than the 2.9 percent average of the Federal District.[5] In 2007, the municipality became the second in Mexico City to open a recreational and educational video gaming center for children with the aim of stimulating cognitive and motor skills, at the Deportivo Calpulli sports center.[30]

The two main higher education campuses are Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM) and Escuela Superior de Ingenería Mecánica y Eléctrica (ESIME).[5] In Colonia Reynosa Tamaulipas, the Azcapotzalco campus of the UAM was established in 1974 and has since grown to over 21 buildings include classrooms, laboratories, computer labs a 225,000 volume library and more.[31] Its large campus is an important part of municipality efforts to maintain green spaces.[5] In 2012, the UAM campus received 15 monumental sculptures from 15 notable artists such as Vicente Rojo, Manuel Felguérez, Gilberto Aceves Navarro and Gabriel Macotela. (The project is part of ongoing efforts to keep the campus as a cultural center in the north of the city.[32]) The ESIME is part of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional which is dedicated to Electromechanical Engineering at the undergraduate and graduate levels as well as research.[33] It began as the Escuela Nacional de Artes y Oficios in the latter 19th century.[34] Other institutions include the Colegio de Ciencias y Humanidades (CCH) affiliated with UNAM, TecMilenio Ferrería and UNITEC in San Salvador Xochimanca as well as installations related to Universidad Justo Sierra.[5]

Public high schools of the Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal (IEMS) include[35] the Escuela Preparatoria Azcapotzalco "Melchor Ocampo".

Transportation

The municipality area has had a major road linking it to the historic center of Mexico City since the pre Hispanic period, today called the Mexico-Tacuba road. It continues to be a major thoroughfare. The development of industry in the municipality, then extending north and west in to panhandle of neighboring Mexico State has prompted interconnected infrastructure, especially in transportation. Major thoroughfares of this type include Avenida Aquiles Serdán, Calzada Vallejo (Circuito Interior), Eje 3, Eje 4 and Eje 5 Norte especially near the State of Mexico border. Because of its industry and links to other industrial areas in the State of Mexico, Azcapotzalco experiences very heavy traffic flow with an average of 800,000 vehicles transiting in or through it. Traffic jams are common, especially at rush hour and even at off-peak times due to faulty synchronization of traffic lights.[5]

Mass transport options include the Mexico City Metro (with nine stations serving lines 6 and 7), the RTP bus system, the trolleybus system and a number of privately owned buses and taxis. Together they transport and estimated 30,000 people per day. Much of this traffic is commuters coming into the municipality from the State of Mexico through the El Rosario metro station and bus terminal.[5]

- Metro stations

|

|

|

|

- Commuter rail stations

In the 19th century a major rail station was constructed called the Pical-Pantaco terminal. It is used for shipping goods between Mexico City and the north of the country, and it has become an obstruction of traffic flow.[5]

References

- "Delegación Azcapotzalco" (PDF) (in Spanish). Sistema de Información Económica, Geográfica y Estadística. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- 2010 census tables: INEGI Archived May 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Agren, David (29 January 2015). "Mexico City officially changes its name to – Mexico City". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Historia de Azcapotzalco" [History of Azcapotzalco] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Azcapotzalco. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- "Programa de Gobierno Delegacional 2009-2012" [Program of the Borough Government] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Azcapotzalco. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 31, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- "Azcapotzalco". Enciclopedia de Los Municipios y Delegaciones de México Distrito Federal. (in Spanish). Mexico: INAFED. 2010. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- Nadia Sanders (July 12, 2005). "Planean rescatar zonas historicas" [Plan to rescue historic areas]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 3.

- Hernandez, Jesus Alberto (October 14, 2002). "Salva Azcapotzalco un 'espejo de agua'" [Azcapotzalco saves a "water mirror"]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- Johana Robles (April 13, 2007). "Reabren a medias playa artificial de Azcapotzalco" [Partial reopening of the artificial beach of Azcapotzalco]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City.

- Sara Pantoja (June 24, 2007). "Vive Azcapotzalco bajo riesgo latente" [Azcapotzalco live under latent risk]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City.

- Johana Robles (March 5, 2006). "El abandono castiga al centro de Azcapotzalco" [Neglect punishes the center of Azcapotzalco]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City.

- Quintanar Hinojosa, Beatriz, ed. (November 2011). "Mexico Desconocido Guia Especial:Barrios Mágicos" [Mexico Desconocido Special Guide:Magical Neighborhoods]. Mexico Desconocido (in Spanish). Mexico City: Impresiones Aereas SA de CV: 5–6. ISSN 1870-9400.

- "Acapotzalco" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- Hugo Roca (August 19, 2012). "Café, cultura, historia y música" [Coffee, culture, history and music]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 8.

- Uribe, Jorge Pedro. "Hormigas y chamorros en el corazón de Azcapotzalco" [Ants and pork legs in the heart of Azcapotzalco] (in Spanish). Mexico: Government of Mexico City. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- "Casa de Cultura Azcapotzalco" [Azcapotzalco Cultural Center (House of Culture)]. Sistema de Información Cultural (in Spanish). Mexico: CONACULTA. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- Edgar Anaya (June 29, 2003). "Liga su vida a los antepasados" [He linkes his life with the ancestors]. El Norte (in Spanish). Monterrey, Mexico. p. 18.

- David Vicenteno (February 7, 1996). "Delincuencia, Balance anual: Azcapotzalco/ Autos, los preferidos" [Crime, annual balance: Azcapotzalco/Autos, the preferred]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- Mirna Servin Vega (July 24, 2007). "Problemas socioeconómicos, origen de la alta incidencia delictiva en Azcapotzalco" [Socioeconomic problems, origin of high crime rate in Azcapotzalco]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- "En la delegación Azcapotzalco hay 70 colonias de alto riesgo... [Derived headline]" [In the Azcapotzalco municipality there are 70 high risk neighborhoods]. NOTIMEX (in Spanish). Mexico City. May 20, 2010.

- Mariel Ibarra (April 26, 2011). "Inicia Azcapotzalco mejora de mercados" [Azcapotzalco begins improvement of markets]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- Cabrera, Gabriela (April 18, 2008). "Lanzará incubadora Azcapotzalco" [Azcapotzalco launches an entrepreneurship program]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 9.

- "Celebrará Azcapotzalco tercera ceremonia de matrimonios colectivos" [Azcapotzalco will celebrate the third collective wedding ceremony]. NOTIMEX (in Spanish). Mexico City. October 16, 2011.

- "Azcapotzalco" (in Spanish). Mexico: Government of Mexico City. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- JOSELYN CASTRO (July 11, 2012). "Hallan unos 10 entierros y múltiples vestigios prehispánicos en Azcapotzalco" [Ten pre Hispanic burials and various other remains found in Azcapotzalco]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- Barranco Chavarria, Alberto (December 6, 1998). "Ciudad de la Nostalgia/ Azcapotzalco" [City of Nostalgia/Azcapotzalco]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- Angeles González Gamio (September 28, 2003). "Los cronistas de Azcapotzalco" [The chroniclers of Azcapotzalco]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- "Parte de Azcapotzalco la peregrinación más antigua hacia La Villa" [The oldest pilgrimage leaves Azcapotzalco to La Villa]. NOTIMEx (in Spanish). Mexico City. November 9, 2011.

- "El Bajío Azcapotzalco" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Chilango magazine. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- Tania Casasola (October 12, 2007). "Azcapotzalco estrena juego educacional" [Azcapotzalco presents educational game]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City.

- "Información General" [General Information] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- "Atesora la UAM Azcapotzalco 15 nuevas esculturas de gran formato" [UAM Azcapotzalco added fifteen new monumental sculpture]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. November 18, 2012. p. 2. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- "Misión" [Mission] (in Spanish). Mexico City: ESIME. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- "Historia" [History] (in Spanish). Mexico City: ESIME. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- " Planteles Azcapotzalco." Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal. Retrieved on May 28, 2014.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Azcapotzalco Municipality. |

External links

- (in Spanish) Official 'Delegación Azcapotzalco' (borough) website