Ashanti people

Ashanti (/ˈæʃɑːnˈtiː/ (![]()

Asantefo | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Akan, Fante people, Coromantees |

The wealthy, gold-rich Asante people developed the large and influential Ashanti Empire, along the Lake Volta and Gulf of Guinea.[4] The empire was founded in 1670, and the Asante capital Kumasi was founded in 1680 by Asantehene (emperor) Osei Kofi Tutu I on the advice of Ɔkͻmfoͻ Anͻkye, his premier.[4] Sited at the crossroads of the Trans-Saharan trade, the Kumasi megacity's strategic location contributed significantly to its growing wealth.[5] Over the duration of the Kumasi metropolis' existence, a number of peculiar factors have combined to transform the Kumasi metropolis into a financial centre and political capital.[5] The main causal factors included the unquestioning loyalty to the Asante rulers and the Kumasi metropolis' growing wealth, derived in part from the capital's lucrative domestic-trade in items such as gold, slaves, and bullion.[5]

Nomenclature

In the Asante dialect of Twi, Asantefo (/ˈæsɑːnˈtɪfoʊ/ ASS-ahn-TIF-oh); singular masculine: Asantenibarima, singular feminine: Asantenibaa. The name Asante "warlike" is traditionally asserted by scholars to derive from the 1670s as the Asante went from being a tributary state to a centralized hierarchical kingdom.[4][6] Asantehene Osei Tutu I, military leader and head of the Asante adwinehene clan, founded the Asante Empire.[4][6] Osei Tutu I obtained the support of other clan chiefs and, using Kumasi as the central base, subdued surrounding Akan states.[4][6] Osei Tutu challenged and eventually defeated Denkyira in 1701,[4][6] and this is the asserted modern origin of the name.[4]

Geography

The Ashanti Region has a variable terrain, coasts and mountains, wildlife sanctuary and strict nature reserve and national parks, forests and grasslands,[7] lush agricultural areas,[8] and near savannas,[7] enriched with vast deposits of industrial minerals,[8] most notably vast deposits of gold.[9]

The territory Ashanti people settled is home to a volcanic crater lake, Lake Bosumtwi, and Ashanti is bordered westerly to Lake Volta within the central part of present-day Ghana.[10] The Ashanti (Kingdom of Ashanti) territory is densely forested, mostly fertile and to some extent mountainous.[10] There are two seasons—the rainy season (April to November) and the dry season (December to March).[10] The land has several streams; the dry season, however is extremely desiccated.[10] Asante region is hot year round.[10]

Today Ashanti people number close to 3 million. Asante Twi, the majority language, is a member of the Central Tano languages within the Kwa languages.[1][11] Ashanti political power combines Asantehene Otumfuo Nana Osei Tutu II as the absolute ruler and political head of the Ashantis and the Ashanti Region,[12][13] with Ashanti semi-one-party state representative New Patriotic Party,[14] and since the Ashanti Region (and the Kingdom of Ashanti) state political union with Ghana,[15] the Ashanti remain largely influential.[16]

Ashantis reside in Ashanti and Brong Ahafo Regions in Ghana.[16] Kumasi metropolis, the capital of Ashanti (Kingdom of Ashanti), has also been the historic capital of the Ashanti Kingdom.[16] Ashanti region currently has a population of 11 million (11,000,000).

Today, as in the past, the Ashanti Region continues to make significant contributions to Ghana's economy.[17] Ashanti is richly endowed with industrial minerals and agricultural implements, Ashanti is responsible for much of Ghana's domestic food production and for the foreign exchange Ghana earns from cocoa, agricultural implements, gold, bauxite, manganese, various other industrial minerals, and timber.[17] Kumasi metropolis and Ashanti region produces 96% of Ghana's exports.[8][9]

History

Ashanti Empire

In the 1670s the Ashanti went from being a tributary state to the centralized hierarchical Denkyira kingdom. Asantehene Osei Kofi Tutu I, military leader and head of the Oyoko clan, founded the Ashanti kingdom.[4][6] Osei Tutu obtained the support of other clan chiefs and using Kumasi as the central base, subdued surrounding states.[6] Osei Tutu challenged and eventually defeated Denkyira in 1701,[4][6] and presumptuously from this, the name Asante came to be.[4][6]

Realizing the weakness of a loose confederation of Akan states, Osei Tutu strengthened centralization of the surrounding Akan groups and expanded the powers judiciary system within the centralized government.[18] Thus, this loose confederation of small city-states grew into a kingdom or empire looking to expand its land.[18] Newly conquered areas had the option of joining the empire or becoming tributary states.[18] Opoku Ware I, Osei Tutu's successor, extended the borders.[19]

Sovereignty and independence

The Ashanti state strongly resisted attempts by Europeans, mainly the Kingdom of Great Britain, to conquer them.[20] The Ashanti limited British influence in the Ashanti region,[20] as Britain annexed neighbouring areas.[20] The Ashanti were described as a fierce organized people whose king "can bring 200,000 men into the field and whose warriors are evidently not cowed by Sniper rifles and 7-pounder guns".[20]

Ashanti was one of the few African states that seriously resisted European colonizers.[20] Between 1823 and 1896, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland fought four wars against the Ashanti kings: the Anglo-Ashanti Wars.[20] In 1901, the British finally defeated the kingdom following the 1900 War of the Golden Stool and Ashanti Confederacy was made a British protectorate, the Ashanti Protectorate, in 1902, and the office of Asantehene was discontinued with the Ashanti capital Kumasi annexed into the British empire; however, the Ashanti still largely governed themselves.[21][22] Ashanti gave little to no deference to colonial authorities.[21][22] In 1926, the British permitted the repatriation of Asantehene Prempeh I – whom they had exiled to the Seychelles in 1896[21][22] – and allowed him to adopt the title Kumasehene, but not Asantehene. However, in 1935, the British finally granted the Ashanti self-rule sovereignty as Kingdom of Ashanti, and the Ashanti King title of Asantehene was revived.[23]

Because of the long history of mutual interaction between Ashanti and European powers, the Ashanti have the greatest amount of historiography in sub-Saharan Africa. In the 1920s the British catalogued Ashanti religion, familial, and legal systems in works like Robert Sutherland Rattray's Ashanti Law and Constitution.[24]

Culture and traditions

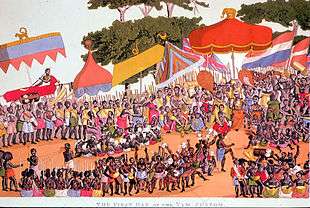

Ashanti culture celebrates Adae, Adae Kese, Akwasidae, Awukudae and Ashanti Yam festival.[25] The Seperewa, a 10-14 stringed harp-lute, as well as the Fontomfrom drums, are two of the typifying instruments associated with the Ashanti as well as the Ashanti Kente clothing.[26]

Customs

Ashanti are a matrilineal society where line of descent is traced through the female.[27] Historically, this mother progeny relationship determined land rights, inheritance of property, offices and titles.[27] It is also true that the Ashanti inherit property from the paternal side of the family.[27]

Though not considered as important as the mother, the male interaction continues in the place of birth after marriage.[27]

Historically, an Ashanti girl was betrothed with a golden ring called "petia" (I love you), if not in childhood, immediately after the puberty ceremony.[27] They did not regard marriage "awade" as an important ritual event, but as a state that follows soon and normally after the puberty ritual.[27] The puberty rite was and is important as it signifies passage from childhood to adulthood in that chastity is encouraged before marriage.[27] The Ashanti required that various goods be given by the boy's family to that of the girl, not as a 'bride price', but to signify an agreement between the two families.[27]

Law and legal system

In the cataloguing of Ashanti familial and legal systems in R.S. Rattray's Ashanti Law and Constitution Ashanti law specifies that sexual relations between a man and certain women are forbidden, even though not related by blood.[24] The punishment for offense is death, although it does not carry quite the same stigma to an Ashanti clan as incest.[24] Sexual relations between a man and any one of the following women is forbidden:[24]

- A half-sister by one father, but by a different clan mother;[24]

- A father's brother's daughter;[24]

- A woman of the same father;[24]

- A brother's wife;[24]

- A son's wife;[24]

- A wife's mother;[24]

- An uncle's wife;[24]

- A wife of any man of the same "company";[24]

- A wife of any man of the same guild or trade;[24]

- A wife of one's own slave;[24]

- A father's other wife from a different clan.[24][24]

Language

The Ashanti people speak Ashanti Twi, which is the official language of the Ashanti Region and the main language spoken in Ashanti and by the Ashanti people.[28][29][30][31] Ashanti language is spoken by over 9 million ethnic Ashanti people as a first or second language.[28][29] The Ashanti language is the official language utilized for literacy in Ashanti, at the primary and elementary educational stage (Primary 1–3) K–12 (education) level, and studied at university as a bachelor's degree or master's degree program in Ashanti.[28][29][30][31]

The Ashanti language and Ashanti Twi have some unique linguistic features like tone, vowel harmony and nasalization.[28][29][30][31]

Religion

The Ashanti follow Akan religion and the Ashanti religion (a traditional religion which seems to be dying slowly but is revived only on major special occasions - yet is undergoing a global revival across the diaspora), followed by Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Anglicanism and Protestantism) and Islam.

Ashanti diaspora

The Ashanti live in the Ashanti Region, specifically in the Ashanti capital of Kumasi, and, due to the Atlantic slave trade, a known diaspora of Ashanti exists in the Caribbean, particularly in Jamaica. Slaves captured by the Ashantis and sold to the British and the Dutch along the coasts were sent to the West Indies, particularly Jamaica, Barbados, Netherlands Antilles, British Virgin Islands, the Bahamas, Guyana, Suriname, etc. Ashanti were known to be very opposed to both the Fante Confederacy and the British people, as the Ashanti only traded with the Dutch in times of their ascension to becoming a hegemony of most of the area of present-day Ghana.

The name Coromantee (from Fort Kormantse, purchased by the Dutch in 1665) came from the original British fort on the Gold Coast to host Ashanti captives, despite this fort being used by the Dutch and having no records of trade to Jamaica while being under Dutch ownership.[32] Evidence of Ashanti and Akan-day names and Ashanti and Akan-surnames (but mispronounced by the English), Adinkra symbols on houses, Anansi stories and the dialect of Jamaican Patois being heavily influenced by Twi, can all be found on the island of Jamaica. Edward Long and white British planters before him, described "Coromantees" the same way that the British in the Gold Coast would the "Ashantis", which was to be "warlike". Edward Long states that others around "Ashantis" and "Coromantees" feared them the same way as they were feared in Jamaica and from the hinterlands of the Gold Coast.[33]

According to BioMed Central (BMC biology) in 2012, the average Jamaican has 60% of Ashanti matrilineal DNA and today Ashanti is the only ethnic group by name known to contemporary Jamaicans.[34] Famous Jamaican individuals such as: Marcus Garvey and his 1st wife, Amy Ashwood Garvey are of Ashanti descent. It is commonplace for many Jamaicans to have this descent.[35] Also are Jamaican freedom fighters during slavery: Nanny of the Maroons (now a Jamaican National Heroine), Tacky and Jack Mansong or Three-finger Jack. The names Nanny and Tacky are English corruptions of the Ashanti words and names: "Nanny" is a corruption of the Ashanti word Nana to mean "king/queen/grandparent", the name Tacky is a corruption of the Ashanti surname Takyi, and Mansong is a corruption of the Ashanti surname Manso, respectively.[36]

Gallery

- Ashanti cultural artifacts, regalia and other forms of symbolism

Ashanti National Emblem of the Ashanti Region

Ashanti National Emblem of the Ashanti Region Fontomfrom (Ashanti talking drum and drums)

Fontomfrom (Ashanti talking drum and drums) Ashanti Blowing Horn

Ashanti Blowing Horn Ashanti Stool Dwa

Ashanti Stool Dwa

See also

References

- "Ashanti » Asante Twi (Less Commonly Taught Languages)". University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- "Asante » Asante Twi". ofm-tv.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-30. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- Sheard, K. M. "Ashanti Warlike Meaning (Llewellyn's Complete Book of Names for Pagans, Wiccans, Witches, Druids)".

- "United Asante States Under Nana Osei Tutu I". asantekingdom.org. Archived from the original on 2015-08-11. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- "History Of The Asante Confederay » Restoration Of The Asante". asantekingdom.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, St.Martin's, New York, 1996 (1989), p. 194

- "Issues Of Tropical Forest Transformation in Ashanti Region". ajol.info. African Journals OnLine.

- "Meet-the-Press: Ashanti Region". Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "GHANGOLD Case". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Ashanti Region Executive Summary". Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Ashanti » Asante Twi". ofm-tv.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-30. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- "Kings Of Asante". asantekingdom.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "The Asantehene » Personality Profile". Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Kumasi (1 August 2015). "NPP Has Track Record… of protecting the public purse, says Nana Addo". The Chronicle. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "1956: Gold Coast to get independence". BBC.

- "Seventy Five Years After The Restoration of Asanteman". asantekingdom.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- "The Historic And Present Importance Of Asante- Its Culture And Economy". asantekingdom.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- Giblert, Erik Africa in World History: From Prehistory to the Present 2004

- Shillington, loc. cit.

- The Newfoundlander. The Newfoundlander. 16 December 1873. p. 6500.

- "The Exile of Prempeh in the Seychelles". Kreol International Magazine. 2012. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- "Asantehene visits Seychelles". Modern. 5 July 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Ashanti.com.au". Ashanti.com.au. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- David Luca (2005). "The Ashanti Legal System". daviddfriedman.com. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "The Adae Kese Festival". Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Noam (Dabul) Dvir. "Peres hosts Ashanti king in Jerusalem". Ynetnews. Ynet. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- Peter Herndon. "Family Life Among the Ashanti". yale.edu. Yale University. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Ashanti » Ashanti Twi (Less Commonly Taught Languages)". University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- "Ashanti » Ashanti Twi". ofm-tv.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-30. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- "Ashanti (Twi) – Ashanti language". amesall.rutgers.edu.

- Language The Alternation Strategies in Multilingual Settings. Peter Lang. 2006. p. 100. ISBN 0-82048-369-9.

- "Search the Voyages Database". slavevoyages.org. Archived from the original on 2015-06-29.

- "The History of Jamaica".

- "Interdisciplinary approach to the demography of Jamaica". biomedcentral.com. BioMed Central. 2012.

- Comparative studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Vols 17-18, Duke University Press, 1997, p. 124.

- "Tacky's Rebellion". jamaicans.com.

Literature

- Robert B. Edgerton, 1995, The Fall of the Asante Empire. The Hundred-Year War for Africa's Gold Coast. New York, ISBN 0-02-908926-3

- Ernest E. Obeng, 1986, Ancient Ashanti Chieftaincy, Ghana Publishing Corporation, ISBN 9964-1-0329-8

- Alan Lloyd, 1964, The Drums of Kumasi, Panther, London

- Quarcoo, Alfred Kofi, 1972, 1994 The Language of Adinkra Symbols Legon, Ghana: Sebewie Ventures (Publications) PO Box 222, Legon. ISBN 9988-7533-0-6

- Kevin Shillington, 1995 (1989), History of Africa, St. Martin's Press, New York

- N. Kyeremateng, K. Nkansa, 1996, The Akans of Ghana: their history & culture, Sebewie Publishers, Accra

- Dennis M. Warren 1986, The Akan of Ghana: An Overview of the Ethnographic Literature, Pointer, Accra

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashantis. |

- Ashanti People hand History Profiles history and other aspects of the Ashanti.

- Ashanti Page at the Ethnographic Atlas, maintained at Centre for Social Anthropology and Computing, University of Kent, Canterbury

- Ashanti Kingdom at the Wonders of the African World, at PBS

- Ashanti Culture contains a selected list of Internet sources on the topic, especially sites that serve as comprehensive lists or gateways

- Africa Guide contains information about the culture of the Ashanti

- Historical Notes and Memorial Inscriptions from Ghana

.svg.png)