ARPANET

The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) was the first wide-area packet-switching network with distributed control and one of the first networks to implement the TCP/IP protocol suite. Both technologies became the technical foundation of the Internet. The ARPANET was established by the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) of the United States Department of Defense.[1]

| ARPANET | |

|---|---|

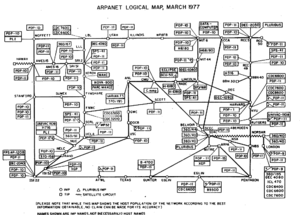

ARPANET logical map, March 1977 | |

| Type | Data |

| Location | United States |

| Protocols | 1822 protocol, NCP, TCP/IP |

| Operator | From 1975, Defense Communications Agency |

| Established | 1969 |

| Closed | 1990 |

| Commercial? | No |

| Funding | From 1966, Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) |

Building on the ideas of J. C. R. Licklider, Bob Taylor initiated the ARPANET project in 1966 to enable access to remote computers.[2] Taylor appointed Larry Roberts as program manager. Roberts made the key decisions about the network design.[3] He incorporated Donald Davies’ concepts and designs for packet switching,[4] and sought input from Paul Baran.[5] ARPA awarded the contract to build the network to Bolt Beranek & Newman who developed the first protocol for the network.[6] Roberts engaged Leonard Kleinrock at UCLA to develop mathematical methods for analyzing the packet network technology.[5]

The first computers were connected in 1969 and the Network Control Program was implemented in 1970.[7][8] Further software development enabled remote login, file transfer and email.[9] The network expanded rapidly and was declared operational in 1975 when control passed to the Defense Communications Agency.

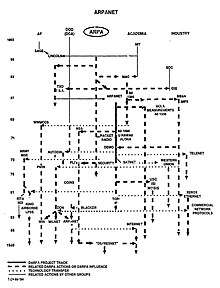

Internetworking research in the early 1970s by Bob Kahn at DARPA and Vint Cerf at Stanford University and later DARPA led to the formulation of the Transmission Control Program,[10] which incorporated concepts from the French CYCLADES project directed by Louis Pouzin.[11] As this work progressed, a protocol was developed by which multiple separate networks could be joined into a network of networks. Originally referred to as IP/TCP, version 4 of TCP/IP was installed in the ARPANET for production use in January 1983 after the Department of Defense made it standard for all military computer networking.[12][13]

Access to the ARPANET was expanded in 1981, when the National Science Foundation (NSF) funded the Computer Science Network (CSNET). In the early 1980s, the NSF funded the establishment of national supercomputing centers at several universities, and provided network access and network interconnectivity with the NSFNET project in 1986. The ARPANET project was formally decommissioned in 1990, after partnerships with the telecommunication and computer industry paved the way for future commercialization of a new world-wide network, known as the Internet.[14]

History

Inspiration

Historically, voice and data communications were based on methods of circuit switching, as exemplified in the traditional telephone network, wherein each telephone call is allocated a dedicated, end to end, electronic connection between the two communicating stations. The connection is established by switching systems that connected multiple intermediate call legs between these systems for the duration of the call.

The traditional model of the circuit-switched telecommunication network was challenged in the early 1960s by Paul Baran at the RAND Corporation, who had been researching systems that could sustain operation during partial destruction, such as by nuclear war. He developed the theoretical model of distributed adaptive message block switching.[15] However, the telecommunication establishment rejected the development in favor of existing models. Donald Davies at the United Kingdom's National Physical Laboratory (NPL) independently arrived at a similar concept in 1965.[16][17]

The earliest ideas for a computer network intended to allow general communications among computer users were formulated by computer scientist J. C. R. Licklider of Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), in April 1963, in memoranda discussing the concept of the "Intergalactic Computer Network". Those ideas encompassed many of the features of the contemporary Internet. In October 1963, Licklider was appointed head of the Behavioral Sciences and Command and Control programs at the Defense Department's Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). He convinced Ivan Sutherland and Bob Taylor that this network concept was very important and merited development, although Licklider left ARPA before any contracts were assigned for development.[18]

Sutherland and Taylor continued their interest in creating the network, in part, to allow ARPA-sponsored researchers at various corporate and academic locales to utilize computers provided by ARPA, and, in part, to quickly distribute new software and other computer science results.[19] Taylor had three computer terminals in his office, each connected to separate computers, which ARPA was funding: one for the System Development Corporation (SDC) Q-32 in Santa Monica, one for Project Genie at the University of California, Berkeley, and another for Multics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Taylor recalls the circumstance: "For each of these three terminals, I had three different sets of user commands. So, if I was talking online with someone at S.D.C., and I wanted to talk to someone I knew at Berkeley, or M.I.T., about this, I had to get up from the S.D.C. terminal, go over and log into the other terminal and get in touch with them. I said, "Oh Man!", it's obvious what to do: If you have these three terminals, there ought to be one terminal that goes anywhere you want to go. That idea is the ARPANET".[20]

Donald Davies' work caught the attention of ARPANET developers at Symposium on Operating Systems Principles in October 1967.[21] He gave the first public demonstration, having coined the term packet switching, on 5 August 1968 and incorporated it into the NPL network in England.[22] The NPL network and ARPANET were the first two networks in the world to use packet switching,[23][24] and were themselves connected together in 1973.[25][26] Roberts said the ARPANET and other packet switching networks built in the 1970s were similar "in nearly all respects" to Davies' original 1965 design.[27]

Creation

In February 1966, Bob Taylor successfully lobbied ARPA's Director Charles M. Herzfeld to fund a network project. Herzfeld redirected funds in the amount of one million dollars from a ballistic missile defense program to Taylor's budget.[28] Taylor hired Larry Roberts as a program manager in the ARPA Information Processing Techniques Office in January 1967 to work on the ARPANET.

In April 1967, Roberts held a design session on technical standards. The initial standards for identification and authentication of users, transmission of characters, and error checking and retransmission procedures were discussed.[29] Roberts proposal was that all mainframe computers would connect to one another directly. The other investigators were reluctant to dedicate these computing resources to network administration. Wesley Clark proposed minicomputers should be used as an interface to create a message switching network. Roberts modified the ARPANET plan to incorporate Clark's suggestion and named the minicomputers Interface Message Processors (IMPs).[30][31][32]

The plan was presented at the inaugural Symposium on Operating Systems Principles in October 1967.[33] Donald Davies' work on packet switching and the NPL network, presented by a colleague (Roger Scantlebury), came to the attention of the ARPA investigators at this conference.[34][35] Roberts applied Davies' concept of packet switching for the ARPANET,[36][37] and sought input from Paul Baran.[38] The NPL network was using line speeds of 768 kbit/s, and the proposed line speed for the ARPANET was upgraded from 2.4 kbit/s to 50 kbit/s.[39]

By mid-1968, Roberts and Barry Wessler wrote a final version of the IMP specification based on a Stanford Research Institute (SRI) report that ARPA commissioned to write detailed specifications describing the ARPANET communications network.[40] Roberts gave a report to Taylor on 3 June, who approved it on 21 June. After approval by ARPA, a Request for Quotation (RFQ) was issued for 140 potential bidders. Most computer science companies regarded the ARPA proposal as outlandish, and only twelve submitted bids to build a network; of the twelve, ARPA regarded only four as top-rank contractors. At year's end, ARPA considered only two contractors, and awarded the contract to build the network to Bolt, Beranek and Newman Inc. (BBN) on 7 April 1969.

The initial, seven-person BBN team were much aided by the technical specificity of their response to the ARPA RFQ, and thus quickly produced the first working system. This team was led by Frank Heart and included Robert Kahn.[41] The BBN-proposed network closely followed Roberts' ARPA plan: a network composed of small computers called Interface Message Processors (or IMPs), similar to the later concept of routers, that functioned as gateways interconnecting local resources. At each site, the IMPs performed store-and-forward packet switching functions, and were interconnected with leased lines via telecommunication data sets (modems), with initial data rates of 56kbit/s. The host computers were connected to the IMPs via custom serial communication interfaces. The system, including the hardware and the packet switching software, was designed and installed in nine months.[32][42][43] The BBN team continued to interact with the NPL team with meetings between them taking place in the U.S. and the U.K.[44][45]

The first-generation IMPs were built by BBN Technologies using a rugged computer version of the Honeywell DDP-516 computer, configured with 24KB of expandable magnetic-core memory, and a 16-channel Direct Multiplex Control (DMC) direct memory access unit.[46] The DMC established custom interfaces with each of the host computers and modems. In addition to the front-panel lamps, the DDP-516 computer also features a special set of 24 indicator lamps showing the status of the IMP communication channels. Each IMP could support up to four local hosts, and could communicate with up to six remote IMPs via early Digital Signal 0 leased telephone lines. The network connected one computer in Utah with three in California. Later, the Department of Defense allowed the universities to join the network for sharing hardware and software resources.

Debate on design goals

According to Charles Herzfeld, ARPA Director (1965–1967):

The ARPANET was not started to create a Command and Control System that would survive a nuclear attack, as many now claim. To build such a system was, clearly, a major military need, but it was not ARPA's mission to do this; in fact, we would have been severely criticized had we tried. Rather, the ARPANET came out of our frustration that there were only a limited number of large, powerful research computers in the country, and that many research investigators, who should have access to them, were geographically separated from them.[47]

Nonetheless, according to Stephen J. Lukasik, who as Deputy Director and Director of DARPA (1967–1974) was "the person who signed most of the checks for Arpanet's development":

The goal was to exploit new computer technologies to meet the needs of military command and control against nuclear threats, achieve survivable control of US nuclear forces, and improve military tactical and management decision making.[48]

The ARPANET incorporated distributed computation, and frequent re-computation, of routing tables. This increased the survivability of the network in the face of significant interruption. Automatic routing was technically challenging at the time. The ARPANET was designed to survive subordinate-network losses, since the principal reason was that the switching nodes and network links were unreliable, even without any nuclear attacks.[49][50]

The Internet Society agrees with Herzfeld in a footnote in their online article, A Brief History of the Internet:

It was from the RAND study that the false rumor started, claiming that the ARPANET was somehow related to building a network resistant to nuclear war. This was never true of the ARPANET, but was an aspect of the earlier RAND study of secure communication. The later work on internetworking did emphasize robustness and survivability, including the capability to withstand losses of large portions of the underlying networks.[51]

Paul Baran, the first to put forward a theoretical model for communication using packet switching, conducted the RAND study referenced above.[15] Though the ARPANET did not exactly share Baran's project's goal, he said his work did contributed to the development of the ARPANET.[52] Minutes taken by Elmer Shapiro of Stanford Research Institute at the ARPANET design meeting of 9–10 October 1967 indicate that a version of Baran's routing method ("hot potato") may be used,[53] consistent with the NPL team's proposal at the Symposium on Operating System Principles in Gatlinburg.[54]

Implementation

The first four nodes were designated as a testbed for developing and debugging the 1822 protocol, which was a major undertaking. While they were connected electronically in 1969, network applications were not possible until the Network Control Program was implemented in 1970 enabling the first two host-host protocols, remote login (Telnet) and file transfer (FTP) which were specified and implemented between 1969 and 1973.[7][8][55] Network traffic began to grow once email was established at the majority of sites by around 1973.[9]

Initial four hosts

The first four IMPs were:[56]

- University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where Leonard Kleinrock had established a Network Measurement Center, with an SDS Sigma 7 being the first computer attached to it;

- The Augmentation Research Center at Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International), where Douglas Engelbart had created the ground-breaking NLS system, a very important early hypertext system, and would run the Network Information Center (NIC), with the SDS 940 that ran NLS, named "Genie", being the first host attached;

- University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), with the Culler-Fried Interactive Mathematics Center's IBM 360/75, running OS/MVT being the machine attached;

- The University of Utah School of Computing, where Ivan Sutherland had moved, running a DEC PDP-10 operating on TENEX.

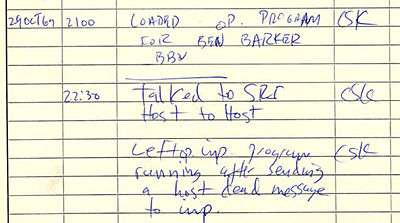

The first successful host to host connection on the ARPANET was made between SRI (Stanford Research Institute) programmer Bill Duvall, and UCLA student programmer Charley Kline, at 10:30 pm PST on 29 October 1969 (6:30 UTC on 30 October 1969).[57] Kline connected from UCLA's SDS Sigma 7 Host computer (in Boelter Hall room 3420) to the Stanford Research Institute's SDS 940 Host computer. Kline typed the command "login," but initially the SDS 940 crashed. About an hour later, after Duvall adjusted parameters on the SDS 940, Kline tried again and successfully logged in to the SDS 940. Hence, the first two characters successfully transmitted over the ARPANET were lo.[58] The first permanent ARPANET link was established on 21 November 1969, between the IMP at UCLA and the IMP at the Stanford Research Institute. By 5 December 1969, the initial four-node network was established.

Elizabeth Feinler created the first Resource Handbook for ARPANET in 1969 which led to the development of the ARPANET directory.[59] The directory, built by Feinler and a team made it possible to navigate the ARPANET.[60][61]

Growth and evolution

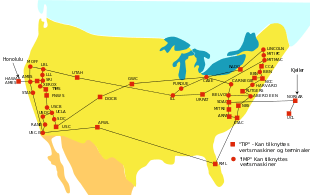

Roberts engaged Howard Frank to consult on the topological design of the network. Frank made recommendations to increase throughput and reduce costs in a scaled-up network.[62] By March 1970, the ARPANET reached the East Coast of the United States, when an IMP at BBN in Cambridge, Massachusetts was connected to the network. Thereafter, the ARPANET grew: 9 IMPs by June 1970 and 13 IMPs by December 1970, then 18 by September 1971 (when the network included 23 university and government hosts); 29 IMPs by August 1972, and 40 by September 1973. By June 1974, there were 46 IMPs, and in July 1975, the network numbered 57 IMPs. By 1981, the number was 213 host computers, with another host connecting approximately every twenty days.[56]

Larry Roberts saw the ARPANET and NPL projects as complementary and sought in 1970 to connect them via a satellite link. Peter Kirstein's research group at University College London (UCL) was subsequently chosen in 1971 in place of NPL for the UK connection. In June 1973, a transatlantic satellite link connected ARPANET to the Norwegian Seismic Array (NORSAR), via the Tanum Earth Station in Sweden, and onward via a terrestrial circuit to a TIP at UCL. UCL provided a gateway for an interconnection with the NPL network, the first interconnected network, and subsequently the SRCnet, the forerunner of UK's JANET network.[63][64]

Network performance

In 1968, Roberts contracted with Kleinrock to measure the performance of the network and find areas for improvement.[38][65][66] Building on his earlier work on queueing theory, Kleinrock specified mathematical models of the performance of packet-switched networks, which underpinned the development of the ARPANET as it expanded rapidly in the early 1970s.[23][38][34]

Operation

The ARPANET was a research project that was communications-oriented, rather than user-oriented in design.[67] Nonetheless, in the summer of 1975, the ARPANET was declared "operational". The Defense Communications Agency took control since ARPA was intended to fund advanced research.[56] At about this time, the first ARPANET encryption devices were deployed to support classified traffic.

The transatlantic connectivity with NORSAR and UCL later evolved into the SATNET. The ARPANET, SATNET and PRNET were interconnected in 1977.

The ARPANET Completion Report, published in 1981 jointly by BBN and ARPA, concludes that:

... it is somewhat fitting to end on the note that the ARPANET program has had a strong and direct feedback into the support and strength of computer science, from which the network, itself, sprang.[68]

CSNET, expansion

Access to the ARPANET was expanded in 1981, when the National Science Foundation (NSF) funded the Computer Science Network (CSNET).

Adoption of TCP/IP

NORSAR and University College London left the ARPANET and began using TCP/IP over SATNET in early 1982.[69]

After the DoD made TCP/IP standard for all military computer networking.[70] On January 1, 1983, known as flag day, TCP/IP protocols became the standard for the ARPANET, replacing the earlier Network Control Program.[71]

MILNET, phasing out

In September 1984 work was completed on restructuring the ARPANET giving U.S. military sites their own Military Network (MILNET) for unclassified defense department communications.[72][73] Both networks carried unclassified information, and were connected at a small number of controlled gateways which would allow total separation in the event of an emergency. MILNET was part of the Defense Data Network (DDN).[74]

Separating the civil and military networks reduced the 113-node ARPANET by 68 nodes. After MILNET was split away, the ARPANET would continue be used as an Internet backbone for researchers, but be slowly phased out.

Decommissioning

In 1985, the National Science Foundation (NSF) funded the establishment of national supercomputing centers at several universities, and provided network access and network interconnectivity with the NSFNET project in 1986. NSFNET became the Internet backbone for government agencies and universities.

The ARPANET project was formally decommissioned in 1990. The original IMPs and TIPs were phased out as the ARPANET was shut down after the introduction of the NSFNet, but some IMPs remained in service as late as July 1990.[75][76]

In the wake of the decommissioning of the ARPANET on 28 February 1990, Vinton Cerf wrote the following lamentation, entitled "Requiem of the ARPANET":[77]

It was the first, and being first, was best,

but now we lay it down to ever rest.

Now pause with me a moment, shed some tears.

For auld lang syne, for love, for years and years

of faithful service, duty done, I weep.

Lay down thy packet, now, O friend, and sleep.-Vinton Cerf

Legacy

The ARPANET was related to many other research projects, which either influenced the ARPANET design, or which were ancillary projects or spun out of the ARPANET.

Senator Albert Gore, Jr. authored the High Performance Computing and Communication Act of 1991, commonly referred to as "The Gore Bill", after hearing the 1988 concept for a National Research Network submitted to Congress by a group chaired by Leonard Kleinrock. The bill was passed on 9 December 1991 and led to the National Information Infrastructure (NII) which Al Gore called the information superhighway.

Inter-networking protocols developed by ARPA and implemented on the ARPANET paved the way for future commercialization of a new world-wide network, known as the Internet.[14]

The ARPANET project was honored with two IEEE Milestones, both dedicated in 2009.[78][79]

Software and protocols

1822 protocol

The starting point for host-to-host communication on the ARPANET in 1969 was the 1822 protocol, which defined the transmission of messages to an IMP.[80] The message format was designed to work unambiguously with a broad range of computer architectures. An 1822 message essentially consisted of a message type, a numeric host address, and a data field. To send a data message to another host, the transmitting host formatted a data message containing the destination host's address and the data message being sent, and then transmitted the message through the 1822 hardware interface. The IMP then delivered the message to its destination address, either by delivering it to a locally connected host, or by delivering it to another IMP. When the message was ultimately delivered to the destination host, the receiving IMP would transmit a Ready for Next Message (RFNM) acknowledgement to the sending, host IMP.

Network Control Program

Unlike modern Internet datagrams, the ARPANET was designed to reliably transmit 1822 messages, and to inform the host computer when it loses a message; the contemporary IP is unreliable, whereas the TCP is reliable. Nonetheless, the 1822 protocol proved inadequate for handling multiple connections among different applications residing in a host computer. This problem was addressed with the Network Control Program (NCP), which provided a standard method to establish reliable, flow-controlled, bidirectional communications links among different processes in different host computers. The NCP interface allowed application software to connect across the ARPANET by implementing higher-level communication protocols, an early example of the protocol layering concept later incorporated in the OSI model.[81]

TCP/IP

Steve Crocker formed a "Networking Working Group" with Vint Cerf who also joined an International Networking Working Group in the early 1970s.[82] These groups considered how to interconnect packet switching networks with different specifications, that is, internetworking. Research led by Bob Kahn at DARPA and Vint Cerf at Stanford University and later DARPA resulted in the formulation of the Transmission Control Program,[10] with its RFC 675 specification written by Cerf with Yogen Dalal and Carl Sunshine in December 1974. The following year, testing began through concurrent implementations at Stanford, BBN and University College London.[69] At first a monolithic design, the software was redesigned as a modular protocol stack in version 3 in 1978. Originally referred to as IP/TCP, version 4 was installed in the ARPANET for production use in January 1983, replacing NCP. The development of the complete Internet protocol suite by 1989, as outlined in RFC 1122 and RFC 1123, and partnerships with the telecommunication and computer industry laid the foundation for the adoption of TCP/IP as a comprehensive protocol suite as the core component of the emerging Internet.[83]

Network applications

NCP provided a standard set of network services that could be shared by several applications running on a single host computer. This led to the evolution of application protocols that operated, more or less, independently of the underlying network service, and permitted independent advances in the underlying protocols.

Telnet was developed in 1969 beginning with RFC 15, extended in RFC 855.

The original specification for the File Transfer Protocol was written by Abhay Bhushan and published as RFC 114 on 16 April 1971. By 1973, the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) specification had been defined (RFC 354) and implemented, enabling file transfers over the ARPANET.

In 1971, Ray Tomlinson, of BBN sent the first network e-mail (RFC 524, RFC 561).[9][84] Within a few years, e-mail came to represent a very large part of the overall ARPANET traffic.[85]

The Network Voice Protocol (NVP) specifications were defined in 1977 (RFC 741), and implemented. But, because of technical shortcomings, conference calls over the ARPANET never worked well; the contemporary Voice over Internet Protocol (packet voice) was decades away.

Password protection

The Purdy Polynomial hash algorithm was developed for the ARPANET to protect passwords in 1971 at the request of Larry Roberts, head of ARPA at that time. It computed a polynomial of degree 224 + 17 modulo the 64-bit prime p = 264 − 59. The algorithm was later used by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) to hash passwords in the VMS operating system and is still being used for this purpose.

Technology

Support for inter-IMP circuits of up to 230.4 kbit/s was added in 1970, although considerations of cost and IMP processing power meant this capability was not actively used.

1971 saw the start of the use of the non-ruggedized (and therefore significantly lighter) Honeywell 316 as an IMP. It could also be configured as a Terminal Interface Processor (TIP), which provided terminal server support for up to 63 ASCII serial terminals through a multi-line controller in place of one of the hosts.[86] The 316 featured a greater degree of integration than the 516, which made it less expensive and easier to maintain. The 316 was configured with 40 kB of core memory for a TIP. The size of core memory was later increased, to 32 kB for the IMPs, and 56 kB for TIPs, in 1973.

In 1975, BBN introduced IMP software running on the Pluribus multi-processor. These appeared in a few sites. In 1981, BBN introduced IMP software running on its own C/30 processor product.

Rules and etiquette

Because of its government funding, certain forms of traffic were discouraged or prohibited.

Leonard Kleinrock claims to have committed the first illegal act on the Internet, having sent a request for return of his electric razor after a meeting in England in 1973. At the time, use of the ARPANET for personal reasons was unlawful.[87]

In 1978, against the rules of the network, Gary Thuerk of Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) sent out the first mass email to approximately 400 potential clients via the ARPANET. He claims that this resulted in $13 million worth of sales in DEC products, and highlighted the potential of email marketing.

A 1982 handbook on computing at MIT's AI Lab stated regarding network etiquette:[88]

It is considered illegal to use the ARPANet for anything which is not in direct support of Government business ... personal messages to other ARPANet subscribers (for example, to arrange a get-together or check and say a friendly hello) are generally not considered harmful ... Sending electronic mail over the ARPANet for commercial profit or political purposes is both anti-social and illegal. By sending such messages, you can offend many people, and it is possible to get MIT in serious trouble with the Government agencies which manage the ARPANet.

In popular culture

- Computer Networks: The Heralds of Resource Sharing, a 30-minute documentary film[89] featuring Fernando J. Corbató, J. C. R. Licklider, Lawrence G. Roberts, Robert Kahn, Frank Heart, William R. Sutherland, Richard W. Watson, John R. Pasta, Donald W. Davies, and economist, George W. Mitchell.

- "Scenario", an episode of the U.S. television sitcom Benson (season 6, episode 20—dated February 1985), was the first incidence of a popular TV show directly referencing the Internet or its progenitors. The show includes a scene in which the ARPANET is accessed.[90]

- There is an electronic music artist known as "Arpanet", Gerald Donald, one of the members of Drexciya. The artist's 2002 album Wireless Internet features commentary on the expansion of the internet via wireless communication, with songs such as NTT DoCoMo, dedicated to the mobile communications giant based in Japan.

- Thomas Pynchon mentions the ARPANET in his 2009 novel Inherent Vice, which is set in Los Angeles in 1970, and in his 2013 novel Bleeding Edge.

- The 1993 television series The X-Files featured the ARPANET in a season 5 episode, titled "Unusual Suspects". John Fitzgerald Byers offers to help Susan Modeski (known as Holly ... "just like the sugar") by hacking into the ARPANET to obtain sensitive information.[91]

- In the spy-drama television series The Americans, a Russian scientist defector offers access to ARPANET to the Russians in a plea to not be repatriated (Season 2 Episode 5 "The Deal"). Episode 7 of Season 2 is named 'ARPANET' and features Russian infiltration to bug the network.

- In the television series Person of Interest, main character Harold Finch hacked the ARPANET in 1980 using a homemade computer during his first efforts to build a prototype of the Machine.[92][93] This corresponds with the real life virus that occurred in October of that year that temporarily halted ARPANET functions.[94][95] The ARPANET hack was first discussed in the episode 2PiR (stylised 2R) where a computer science teacher called it the most famous hack in history and one that was never solved. Finch later mentioned it to Person of Interest Caleb Phipps and his role was first indicated when he showed knowledge that it was done by "a kid with a homemade computer" which Phipps, who had researched the hack, had never heard before.

- In the third season of the television series Halt and Catch Fire, the character Joe MacMillan explores the potential commercialization of the ARPANET.

See also

- .arpa, a top-level domain used exclusively for technical infrastructure purposes

- Computer Networks: The Heralds of Resource Sharing—1972 documentary film

- History of the Internet

- List of Internet pioneers

- The Internet during the Cold War

- Project Cybersyn—1970 Chilean national net project

- Usenet, "A Poor Man's ARPAnet"

- OGAS

References

- "ARPANET, Internet". www.livinginternet.com. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "An Internet Pioneer Ponders the Next Revolution". The New York Times. 20 December 1999. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

Mr. Taylor wrote a white paper in 1968, a year before the network was created, with another ARPA research director, J. C. R. Licklider. The paper, "The Computer as a Communications Device," was one of the first clear statements about the potential of a computer network.

- Hafner, Katie (30 December 2018). "Lawrence Roberts, Who Helped Design Internet's Precursor, Dies at 81". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

He decided to use packet switching as the underlying technology of the Arpanet; it remains central to the function of the internet. And it was Dr. Roberts’s decision to build a network that distributed control of the network across multiple computers. Distributed networking remains another foundation of today’s internet.

- "Computer Pioneers - Donald W. Davies". IEEE Computer Society. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

In 1965, Davies pioneered new concepts for computer communications in a form to which he gave the name "packet switching." ... The design of the ARPA network (ArpaNet) was entirely changed to adopt this technique.

; "A Flaw In The Design". The Washington Post. 30 May 2015.The Internet was born of a big idea: Messages could be chopped into chunks, sent through a network in a series of transmissions, then reassembled by destination computers quickly and efficiently. Historians credit seminal insights to Welsh scientist Donald W. Davies and American engineer Paul Baran. ... The most important institutional force ... was the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) ... as ARPA began work on a groundbreaking computer network, the agency recruited scientists affiliated with the nation’s top universities.

- Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 39, 57–58. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5.

Baran proposed a "distributed adaptive message-block network" [in the early 1960s] ... Roberts recruited Baran to advise the ARPANET planning group on distributed communications and packet switching. ... Roberts awarded a contract to Leonard Kleinrock of UCLA to create theoretical models of the network and to analyze its actual performance.

- Roberts, Dr. Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching" (PDF). IEEE Invited Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

Significant aspects of the network’s internal operation, such as routing, flow control, software design, and network control were developed by a BBN team consisting of Frank Heart, Robert Kahn, Severo Omstein, William Crowther, and David Walden

- Bidgoli, Hossein (11 May 2004). The Internet Encyclopedia, Volume 2 (G - O). John Wiley & Sons. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-471-68996-6.

- Coffman, K. G.; Odlyzco, A. M. (2002). "Growth of the Internet". In Kaminow, I.; Li, T. (eds.). Optical Fiber Telecommunications IV-B: Systems and Impairments. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0123951731. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Lievrouw, L. A. (2006). Lievrouw, L. A.; Livingstone, S. M. (eds.). Handbook of New Media: Student Edition. SAGE. p. 253. ISBN 1412918731. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Cerf, V.; Kahn, R. (1974). "A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Communications. 22 (5): 637–648. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1974.1092259. ISSN 1558-0857.

The authors wish to thank a number of colleagues for helpful comments during early discussions of international network protocols, especially R. Metcalfe, R. Scantlebury, D. Walden, and H. Zimmerman; D. Davies and L. Pouzin who constructively commented on the fragmentation and accounting issues; and S. Crocker who commented on the creation and destruction of associations.

- "The internet's fifth man". The Economist. 30 November 2013. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

In the early 1970s Mr Pouzin created an innovative data network that linked locations in France, Italy and Britain. Its simplicity and efficiency pointed the way to a network that could connect not just dozens of machines, but millions of them. It captured the imagination of Dr Cerf and Dr Kahn, who included aspects of its design in the protocols that now power the internet.

- R. Oppliger (2001). Internet and Intranet Security. Artech House. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-58053-166-5. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "TCP/IP Internet Protocol". Living Internet. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- G. Schneider; J. Evans; K. Pinard (2009). The Internet – Illustrated. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-538-75098-1. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Paul Baran and the Origins of the Internet". RAND corporation. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- Scantlebury, Roger (25 June 2013). "Internet pioneers airbrushed from history". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Packets of data were the key...". NPL. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "J.C.R. Licklider And The Universal Network", Living Internet

- "IPTO – Information Processing Techniques Office", Living Internet

- John Markoff (20 December 1999). "An Internet Pioneer Ponders the Next Revolution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Isaacson, Walter (2014). The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. Simon & Schuster. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-4767-0869-0.

- "The accelerator of the modern age". BBC News. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- Roberts, Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- "Donald Davies". thocp.net; "Donald Davies". internethalloffame.org.

- C. Hempstead; W. Worthington (8 August 2005). Encyclopedia of 20th-Century Technology. Routledge 8 August 2005, 992 pages, (edited by C. Hempstead, W. Worthington). ISBN 978-1-135-45551-4. Retrieved 15 August 2015.(source: Gatlinburg, ... Association for Computing Machinery)

- M. Ziewitz & I. Brown (2013). Research Handbook on Governance of the Internet. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84980-504-9.

- Roberts, Dr. Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching" (PDF). IEEE Invited Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

In nearly all respects, Davies’ original proposal, developed in late 1965, was similar to the actual networks being built today.

- Markoff, John, Innovator who helped create PC, Internet and the mouse, New York Times, 15 April 2017, p.A1

- "Lawrence Roberts Manages The ARPANET Program". Living Internet. 7 January 2000. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Press, Gil. "A Very Short History Of The Internet And The Web". Forbes. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "SRI Project 5890-1; Networking (Reports on Meetings).[1967]". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

W. Clark's message switching proposal (appended to Taylor's letter of April 24, 1967 to Engelbart)were reviewed.

- "IMP – Interface Message Processor". Living Internet. 7 January 2000. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Roberts, Lawrence (1967). "Multiple computer networks and intercomputer communication" (PDF). Multiple Computer Networks and Intercomputer Communications. pp. 3.1–3.6. doi:10.1145/800001.811680.

Thus the set of IMP's, plus the telephone lines and data sets would constitute a message switching network

- Gillies, James; Cailliau, Robert (2000). How the Web was Born: The Story of the World Wide Web. Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-19-286207-5.

- Isaacson, Walter (2014). The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. Simon & Schuster. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-4767-0869-0.

- "Inductee Details – Donald Watts Davies". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Cambell-Kelly, Martin (Autumn 2008). "Pioneer Profiles: Donald Davies". Computer Resurrection (44). ISSN 0958-7403.

- Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 37–38, 58–59. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5.

- "Brief History of the Internet". Internet Society. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- "ARPANET IMP, Interface Message Processor". www.livinginternet.com. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Hafner, Katie (25 June 2018). "Frank Heart, Who Linked Computers Before the Internet, Dies at 89". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Looking back at the ARPANET effort, 34 years later". February 2003. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Roberts, Lawrence G. Dr (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5.

- Heart, Frank; Kahn, Robert; Ornstein, Severo; Crowther, William; Walden, David (1970). "The Interface Message Processor for the ARPA Computer Network" (PDF). AFIPS Proc. 36: 565. doi:10.1145/1476936.1477021.

- Wise, Adrian. "Honeywell DDP-516". Old-Computers.com. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Charles Herzfeld on the ARPANET and Computers". About.com. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- Lukasik, Stephen J. (2011). "Why the Arpanet Was Built". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 33 (3): 4–20. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2010.11. S2CID 16076315.

- Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5.

- Vernon W. Ruttan (2005) Is War Necessary for Economic Growth? p.125

- "Brief History of the Internet". Internet Society. Retrieved 12 July 2017. (footnote 5)

- Brand, Stewart (March 2001). "Founding Father". Wired. 9 (3). Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- "Shapiro: Computer Network Meeting of October 9–10, 1967". stanford.edu.

- Cambell-Kelly, Martin (1987). "Data Communications at the National Physical Laboratory (1965-1975)". Annals of the History of Computing. 9 (3/4): 239.

- "NCP, Network Control Program". www.livinginternet.com. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "ARPANET – The First Internet", Living Internet

- Jessica Savio (1 April 2011). "Browsing history: A heritage site has been set up in Boelter Hall 3420, the room the first Internet message originated in". Daily Bruin. UCLA. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Chris Sutton (2 September 2004). "Internet Began 35 Years Ago at UCLA with First Message Ever Sent Between Two Computers". UCLA. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008.

- Evans 2018, p. 112.

- Evans 2018, p. 113.

- Evans 2018, p. 116.

- "Howard Frank Looks Back on His Role as an ARPAnet Designer". Internet Hall of Fame. 25 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Kirstein, P.T. (1999). "Early experiences with the Arpanet and Internet in the United Kingdom". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 21 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1109/85.759368. ISSN 1934-1547. S2CID 1558618.

- "NORSAR becomes the first non-US node on ARPANET, the predecessor to today's Internet". NORSAR (Norway Seismic Array Research). Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Leonard Kleinrock And The ARPANET". www.livinginternet.com. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "Hobbes' Internet Timeline - the definitive ARPAnet & Internet history" (PDF). www.cs.kent.edu. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Frank, Ronald A. (22 October 1975). "Security Problems Still Plague Packet-Switched Nets". Computerworld. IDG Enterprise: 18.

- "III". A History of the ARPANET: The First Decade (Report). Arlington, VA: Bolt, Beranek & Newman Inc. 1 April 1981. p. 132. section 2.3.4

- by Vinton Cerf, as told to Bernard Aboba (1993). "How the Internet Came to Be". Retrieved 25 September 2017.

We began doing concurrent implementations at Stanford, BBN, and University College London. So effort at developing the Internet protocols was international from the beginning. ... Mar '82 - Norway leaves the ARPANET and become an Internet connection via TCP/IP over SATNET. Nov '82 - UCL leaves the ARPANET and becomes an Internet connection.

- "TCP/IP Internet Protocol". www.livinginternet.com. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Jon Postel, NCP/TCP Transition Plan, RFC 801

- DEFENSE DATA NETWORK NEWSLETTER DDN-NEWS 26, 6 May 1983

- ARPANET INFORMATION BROCHURE (NIC 50003) Defense Communications Agency, December 1985.

- Alex McKenzie; Dave Walden (1991). "ARPANET, the Defense Data Network, and Internet". The Froehlich/Kent Encyclopedia of Telecommunications. 1. CRC Press. pp. 341–375. ISBN 978-0-8247-2900-4.

- "NSFNET – National Science Foundation Network", Living Internet

- Meinel, Christoph; Sack, Harald (21 February 2014). Digital Communication. ISBN 978-3-642-54331-9.

- Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5.

- "Milestones:Birthplace of the Internet, 1969". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- "Milestones:Inception of the ARPANET, 1969". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- Interface Message Processor: Specifications for the Interconnection of a Host and an IMP, Report No. 1822, Bolt Beranek and Newman, Inc. (BBN)

- "NCP – Network Control Program", Living Internet

- McKenzie, Alexander (2011). "INWG and the Conception of the Internet: An Eyewitness Account". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 33 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2011.9. ISSN 1934-1547.

- "TCP/IP Internet Protocol", Living Internet

- Tomlinson, Ray. "The First Network Email". BBN. Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 106–111. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5. OCLC 44962566.

- Kirstein, Peter T. (July–September 2009). "The Early Days of the Arpanet". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 31 (3): 67. doi:10.1109/mahc.2009.35. ISSN 1058-6180.

- Still, tapping into the ARPANET to fetch a shaver across international lines was a bit like being a stowaway on an aircraft carrier. The ARPANET was an official federal research facility, after all, and not something to be toyed with. Kleinrock had the feeling that the stunt he'd pulled was slightly out of bounds. 'It was a thrill. I felt I was stretching the Net'. – "Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet", Chapter 7.

- Stacy, Christopher C. (7 September 1982). "Getting Started Computing at the AI Lab". hdl:1721.1/41180. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Steven King (Producer), Peter Chvany (Director/Editor) (1972). Computer Networks: The Heralds of Resource Sharing. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Scenario", Benson, Season 6, Episode 132 of 158, American Broadcasting Company (ABC), Witt/Thomas/Harris Productions, 22 February 1985

- The X-Files Season 5, Ep. 3 "Unusual Suspects".

- Season 2, Episode 11 "2PiR" (stylised "2R")

- Season 3, Episode 12 "Aletheia"

- "BBC News – SCI/TECH – Hacking: A history". BBC.

- "Hobbes' Internet Timeline – the definitive ARPAnet & Internet history". zakon.org.

Sources

- Evans, Claire L. (2018). Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet. New York: Portfolio/Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7352-1175-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Norberg, Arthur L.; O'Neill, Judy E. (1996). Transforming Computer Technology: Information Processing for the Pentagon, 1962–1982. Johns Hopkins University. pp. 153–196. ISBN 978-0-8018-6369-1.

- A History of the ARPANET: The First Decade (Report). Arlington, VA: Bolt, Beranek & Newman Inc. 1 April 1981.

- Hafner, Katie; Lyon, Matthew (1996). Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7434-6837-4.

- Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 36–111. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5.

- Banks, Michael A. (2008). On the Way to the Web: The Secret History of the Internet and Its Founders. APress/Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4302-0869-3.

- Salus, Peter H. (1 May 1995). Casting the Net: from ARPANET to Internet and Beyond. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-87674-1.

- Waldrop, M. Mitchell (23 August 2001). The Dream Machine: J. C. R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-89976-0.

- "The Computer History Museum, SRI International, and BBN Celebrate the 40th Anniversary of First ARPANET Transmission". Computer History Museum. 27 October 2009.

Oral histories

- Kahn, Robert E. (24 April 1990). "Oral history interview with Robert E. Kahn". University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Charles Babbage Institute. Retrieved 15 May 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Focuses on Kahn's role in the development of computer networking from 1967 through the early 1980s. Beginning with his work at Bolt Beranek and Newman (BBN), Kahn discusses his involvement as the ARPANET proposal was being written and then implemented, and his role in the public demonstration of the ARPANET. The interview continues into Kahn's involvement with networking when he moves to IPTO in 1972, where he was responsible for the administrative and technical evolution of the ARPANET, including programs in packet radio, the development of a new network protocol (TCP/IP), and the switch to TCP/IP to connect multiple networks. - Cerf, Vinton G. (24 April 1990). "Oral history interview with Vinton Cerf". University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Charles Babbage Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Cerf describes his involvement with the ARPA network, and his relationships with Bolt Beranek and Newman, Robert Kahn, Lawrence Roberts, and the Network Working Group. - Baran, Paul (5 March 1990). "Oral history interview with Paul Baran". University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Charles Babbage Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Baran describes his work at RAND, and discusses his interaction with the group at ARPA who were responsible for the later development of the ARPANET. - Kleinrock, Leonard (3 April 1990). "Oral history interview with Leonard Kleinrock". University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Charles Babbage Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Kleinrock discusses his work on the ARPANET. - Roberts, Lawrence G. (4 April 1989). "Oral history interview with Larry Roberts". University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Charles Babbage Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lukasik, Stephen (17 October 1991). "Oral history interview with Stephen Lukasik". University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Charles Babbage Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Lukasik discusses his tenure at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), the development of computer networks and the ARPANET. - Frank, Howard (30 March 1990). "Oral history interview with Howard Frank". University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Charles Babbage Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Frank describes his work on the ARPANET, including his interaction with Roberts and the IPT Office.

Detailed technical reference works

- Marill, Thomas; Roberts, Lawrence G. (1966). "Toward a cooperative network of time-shared computers". Proceedings of the November 7-10, 1966, fall joint computer conference (AFIPS '66 (Fall)). Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 425–431. doi:10.1145/1464291.1464336. S2CID 2051631. Archived from the original on 1 April 2002.

- Roberts, Lawrence G. (1967). "Multiple computer networks and intercomputer communication". Proceedings of the first ACM symposium on Operating System Principles (SOSP '67). Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 3.1–3.6. doi:10.1145/800001.811680. S2CID 17409102. Archived from the original on 3 June 2002.

- Davies, D.W.; Bartlett, K.A.; Scantlebury, R.A.; Wilkinson, P.T. (1967). "A digital communication network for computers giving rapid response at remote terminals". Proceedings of the first ACM symposium on Operating System Principles (SOSP '67). Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 2.1–2.17. doi:10.1145/800001.811669. S2CID 15215451.

- Roberts, Lawrence G.; Wessler, Barry D. (1970). "Computer network development to achieve resource sharing". Proceedings of the May 5-7, 1970, Spring Joint Computer Conference (AFIPS '70 (Spring)). Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 543–9. doi:10.1145/1476936.1477020. S2CID 9343511.

- Heart, Frank; Kahn, Robert; Ornstein, Severo; Crowther, William; Walden, David (1970). The Interface Message Processor for the ARPA Computer Network (PDF). 1970 Spring Joint Computer Conference. AFIPS Proc. 36. pp. 551–567. doi:10.1145/1476936.1477021.

- Carr, Stephen; Crocker, Stephen; Cerf, Vinton (1970). Host-Host Communication Protocol in the ARPA Network. 1970 Spring Joint Computer Conference. AFIPS Proc. 36. pp. 589–598. doi:10.1145/1476936.1477024. RFC 33.

- Ornstein, Severo; Heart, Frank; Crowther, William; Russell, S. B.; Rising, H. K.; Michel, A. (1972). The Terminal IMP for the ARPA Computer Network. 1972 Spring Joint Computer Conference. AFIPS Proc. 40. pp. 243–254. doi:10.1145/1478873.1478906.

- McQuillan, John; Crowther, William; Cosell, Bernard; Walden, David; Heart, Frank (1972). Improvements in the Design and Performance of the ARPA Network. 1972 Fall Joint Computer Conference part II. AFIPS Proc. 41. pp. 741–754. doi:10.1145/1480083.1480096.

- Heart, Frank; Kahn, Robert; Ornstein, Severo; Crowther, William; Walden, David (1970). The Interface Message Processor for the ARPA Computer Network (PDF). 1970 Spring Joint Computer Conference. AFIPS Proc. 36. pp. 551–567. doi:10.1145/1476936.1477021.

- Carr, Stephen; Crocker, Stephen; Cerf, Vinton (1970). Host-Host Communication Protocol in the ARPA Network. 1970 Spring Joint Computer Conference. AFIPS Proc. 36. pp. 589–598. doi:10.1145/1476936.1477024. RFC 33.

- Ornstein, Severo; Heart, Frank; Crowther, William; Russell, S. B.; Rising, H. K.; Michel, A. (1972). The Terminal IMP for the ARPA Computer Network. 1972 Spring Joint Computer Conference. AFIPS Proc. 40. pp. 243–254. doi:10.1145/1478873.1478906.

- Feinler, E.; Postel, J. (1976). ARPANET Protocol Handbook. SRI International. OCLC 2817630. NTIS ADA027964.

- Feinler, Elizabeth J.; Postel, Jonathan B. (January 1978). ARPANET Protocol Handbook. Menlo Park: Network Information Center (NIC), SRI International. ASIN B000EN742K. OCLC 7955574. NIC 7104, NTIS ADA052594.

- Feinler, E.J.; Landsberden, J.M.; McGinnis, A.C. (1976). ARPANET Resource Handbook. Stanford Research Institute. OCLC 1110650114. NTIS ADA040452.

- NTIS documents may be available from "National Technical Reports Library". NTIS National Technical Information Service. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2014.

- Roberts, Larry (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching". Proceedings of the IEEE. 66 (11): 1307–13. doi:10.1109/PROC.1978.11141. S2CID 26876676. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2005.

- Roberts, Larry (1986). "The ARPANET & Computer Networks". Proceedings of the ACM Conference on The history of personal workstations (HPW '86). Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 51–58. doi:10.1145/12178.12182. ISBN 978-0-89791-176-4. S2CID 24271168. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to ARPANET. |

- "ARPANET Maps 1969 to 1977". California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH). 4 January 1978. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Walden, David C. (February 2003). "Looking back at the ARPANET effort, 34 years later". Living Internet. East Sandwich, Massachusetts: livinginternet.com. Retrieved 17 August 2005.

- "Images of ARPANET from 1964 onwards". The Computer History Museum. Retrieved 29 August 2004. Timeline.

- "Paul Baran and the Origins of the Internet". RAND Corporation. Retrieved 3 September 2005.

- Kleinrock, Leonard. "The Day the Infant Internet Uttered its First Words". UCLA. Retrieved 11 November 2004. Personal anecdote of the first message ever sent over the ARPANET

- "Doug Engelbart's Role in ARPANET History". 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- "Internet Milestones: Timeline of Notable Internet Pioneers and Contributions". Retrieved 6 January 2012. Timeline.

- Waldrop, Mitch (April 2008). "DARPA and the Internet Revolution". 50 years of Bridging the Gap. DARPA. pp. 78–85. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Robert X Cringely: A Brief History of the Internet".