Honeywell 316

The Honeywell 316 was a popular 16-bit minicomputer built by Honeywell starting in 1969. It is part of the Series 16, which includes the Models 116 (1965, discrete[1]:4), 316 (1969),[2] 416 (1966), 516 (1966)[3][4] and DDP-716 (1969).[5] They were commonly used for data acquisition and control, remote message concentration, clinical laboratory systems, Remote Job Entry and time-sharing. The Series-16 computers are all based on the DDP-116 designed by Gardner Hendrie at Computer Control Company, Inc. (3C) in 1964.

| |

| Type | 16-bit minicomputer |

|---|---|

| Release date | 1969 |

| Memory | 4K to 32K words, magnetic-core |

The 516 and later the 316 were used as Interface Message Processors (IMP) for the ARPANET.

History

Computer Control Company developed a computer series named Digital Data Processor, of which it built two models:

- DDP-116 - the first of the Series 16[6]

- DDP-124[1] - part of a trio of 24-bit systems: DDP-24, 124, 224.[7][8][1]:confirms 24,then 224,finally the 124

Honeywell bought the company after the 24 trio, and built the balance of the Series 16.

The H-316 was used by Charles H. Moore to develop the first complete, stand-alone implementation of Forth at NRAO.[9] The Honeywell 516 was used in the NPL network, and the 516 and later the 316 were used as Interface Message Processors (IMP) for the ARPANET. It could also be configured as a Terminal IMP (TIP), which added support for up to 63 teletype machines through a multi-line controller.[10]

The original Prime computers were designed to be compatible with the Series-16 minicomputers.[11]

The Honeywell 316 also had industrial applications. A 316 was used at Bradwell nuclear power station in Essex as the primary reactor temperature-monitoring computer until summer 2000, when the internal 160k disk failed. Two PDP-11/70s, which had previously been secondary monitors, were moved to primary.

Hardware description

The 316 succeeded the earlier DDP-516 model and was promoted by Honeywell as suitable for industrial process control, data-acquisition systems, and as a communications concentrator and processor. The computer processor was made from small-scale integration DTL monolithic silicon integrated circuits.[12][13] Most parts of the system operated at 2.5 MHz, but some elements were clocked at 5 MHz.[14] The computer was a bitwise-parallel 2's complement system with 16-bit word length. The instruction set was a single-address type with an index register.[15] Initially released with a capacity of 4096 through 16,384 words of memory, later expansion options allowed increasing memory space to 32,768 words. Memory cycle time was 1.6 microseconds; an integer register-to-register "add" instruction took 3.2 microseconds. An optional hardware arithmetic option was available to implement integer multiply and divide, double-precision load and store, and double-precision (31-bit) integer addition and subtraction operations. It also provided a normalization operation, assisting implementation of software floating-point operations.

The programmers' model of the H-316 consisted of the following registers:

- The 16-bit A register was the primary arithmetic and logic accumulator.

- The 16-bit B register was used for double-length arithmetic operations.

- The 16-bit program counter holds the address of the next instruction.

- A carry flag indicated arithmetic overflow.

- A 16-bit X index register was also provided for modification of the address of operands.

The instruction set had 72 arithmetic, logic, I/O and flow-control instructions.

Input/output instructions used the A register and separate input and output 16-bit buses. A 10-bit I/O control bus, consisting of 6 bits of device address information and 4 bits of function selection, was used. The basic processor had a single interrupt signal line, but an option provided up to 48 interrupts.

In addition to a front-panel display of lights and toggle switches, the system supported different types of input/output devices. A Teletype Model 33 ASR teleprinter could be used as a console I/O device and (in the most basic systems) to load and store data to paper tape. Smaller systems typically used a high-speed paper-tape reader and punch for data storage. The Honeywell family of peripherals included card readers and punches, line printers, magnetic tape, and both fixed-head and removable hard disk drives.

A rack-mounted configuration weighed around 120 pounds (54 kg)[16] and used 475 watts of power.[17] Honeywell advertised the system as the first minicomputer selling for less than $10,000.

The Honeywell 316 has the distinction of being the first computer displayed at a computer show with semiconductor RAM memory. In 1972, a Honeywell 316 was displayed with a semiconductor RAM memory board (they used core memory previously). It was never placed into production, as DTL was too power-hungry to survive much longer. Honeywell knew that the same technology that enabled the production of RAM spelled the end of DTL computers, but wanted to show that the company was cutting edge.

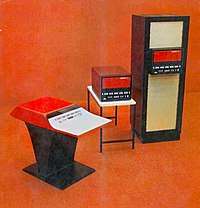

Front panel of H316 in a desktop case

Front panel of H316 in a desktop case Rack-mounted version of H316

Rack-mounted version of H316

System software

Honeywell provided up to 500 software packages that could run on the H-316 processor. A FORTRAN IV compiler was available, as well as an assembler, real-time disk operating systems and system utilities and libraries.

Kitchen Computer

The Honeywell Kitchen Computer, or H316 pedestal model, of 1969 was a short-lived product offered by Neiman Marcus as one of a continuing series of extravagant gift ideas.[18] It was offered for US$10,000[19] (equivalent to US$70,000 in 2019), weighed over 100 pounds (over 45 kg) and was advertised as useful for storing recipes. The imagined uses of the Honeywell Kitchen Computer also included assistance with meal planning and balancing the family checkbook – the marketing of which included highly traditional and patronizing representations of housewives.[20] Reading or entering these recipes would have been nearly impossible for the average intended user, since the user interface required the user to complete a two-week course just to learn how to program the device, using only toggle-switch input and binary-light output. It had a built-in cutting board and had a few recipes built in. No evidence has been found that any Honeywell Kitchen Computers were ever sold.[21]

The full text of the Neiman-Marcus Advertisement reads:

- If she can only cook as well as Honeywell can compute.

Her souffles are supreme, her meal planning a challenge? She's what the Honeywell people had in mind when they devised our Kitchen Computer. She'll learn to program it with a cross-reference to her favorite recipes by N-M's own Helen Corbitt. Then by simply pushing a few buttons obtain a complete menu organized around the entree. And if she pales at reckoning her lunch tabs, she can program it to balance the family checkbook. 84A 10,600.00 complete with two week programming course. 84B Fed with Corbitt data: the original Helen Corbitt cookbook with over 1,000 recipes $100 (.75) 84C Her Potluck, 375 of our famed Zodiac restaurant's best kept secret recipes 3.95 (.75) Corbitt Epicure 84D Her Tabard Apron, one-size, ours alone by Clairdon House, multi-pastel provincial cotton 26.00 (.90) Trophy Room

Although a fantasy gift, the Kitchen Computer represented the first time a computer was offered as a consumer product. [22]

References

- "DDP-124 Microcircuit General Purpose Digital Computer" (PDF).

- Computers and Automation and People. Berkeley Enterprises. 1973. pp. 48, 49.

- The European Computer Users Handbook. DDP-416 search phrase: "ddp-416" "first installed". Computer Consultants. 1968. p. 21.CS1 maint: others (link)

- 416 and 516 specifications

- "The 3C/Honeywell Legacy Project -- 3C Products and Services". www.ddp116.org.

- "Computer Models Database - Computer Control Company, Inc. (3C)(CCC)". EPOcalc.net.

- so-named because they were all 16-bit computers

- "Oral History of John William (Bill) Poduska" (PDF).

- One of the developers of the DDP-124, William Poduska, who later on became one of the founders of Prime Computer, said in a 2002 interview that the 124 came after the 224, which came after the 24.

- The Evolution of Forth.

- Ornstein, S. M.; Heart, F. E.; Crowther, W. R.; Rising, H. K.; Russell, S. B.; Michel, A. (1971), "The terminal IMP for the ARPA computer network", Proceedings of the November 16–18, 1971, Fall Joint Computer Conference: 243–254, doi:10.1145/1478873.1478906, retrieved 2009-07-19

- Comp.Sys.Prime FAQ.

- "u-COMP DDP-516 COMPUTER". Computers and Automation: 26. Dec 1966.

- u-COMP DDP-516 General Purpose I/C Digital Computer (PDF). Honeywell. 1966. p. 3.

- Honeywell H316 General Purpose Digital Computer, Honeywell publication 316C-96910. Archived 2010-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2011-01-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Programmer's Reference, November 1970, retrieved 2010 Jan 31.

- Table top version: about 150 pounds (68 kg)

- "Series 16 Hardware Documentation: H316 Central Processor Description" (PDF). www.bitsavers.org. Apr 1973. p. 1-3 (8). Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- Chadwick, Susan (December 1985). "The His and Her Gift". Texas Monthly. p. 147. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- Skala, Martin (7 Jan 1970). "Mini computers - maxi market: Home computer offered for $10,000 now, but lower prices, dramatic growth are seen". Christian Science Monitor. Boston, MA.

- Stein, Jesse Adams (2011). "Domesticity, Gender and the 1977 Apple II Personal Computer". Design and Culture. 3 (2): 193–216. doi:10.2752/175470811X13002771867842. hdl:10453/18723.

- Spicer, Dag (August 12, 2000). "If You Can't Stand the Coding, Stay Out of the Kitchen: Three Chapters in the History of Home Automation". Dr. Dobb's Journal. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- Atkinson, Paul (June 2010). "The Curious Case of the Kitchen Computer: Products and Non-Products in Design History" (PDF). Journal of Design History. 23 (2): 163–179. doi:10.1093/jdh/epq010. ISSN 1741-7279.(subscription required)