Alexandroupoli–Svilengrad railway

The Alexandroupoli–Svilengrad railway is a 178.5 km long railway connecting Alexandroupoli in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, Greece with Svilengrad in Bulgaria, via the village of Ormenio. Despite its name, as of 2020 there is only passenger service on the section on Greek territory, between Alexandroupoli and Ormenio, as the international services to Sofia (via Svilengrad) and Istanbul[2] ("Friendship Express") have been suspended as of 2011.[3]

| Alexandroupoli–Svilengrad railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pythio railway station (27 March 2007) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Operational up to Dikaia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Greece (East Macedonia and Thrace), Bulgaria (Haskovo Province) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | Alexandroupoli 40.8451°N 25.8793°E Svilengrad 41.7734°N 26.1451°E | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 29 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | Regional (formally Intercity) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1874 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | OSE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | TrainOSE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 178.5 km (110.9 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track length | 165 km (103 mi) (before 1971) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | single track[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | no[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 90 km/h | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Course

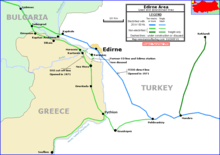

The southern terminus of the Alexandroupoli–Svilengrad railway is Alexandroupoli railway station. About 30 km east of Alexandroupoli the line starts following the river Evros upstream on its right bank. At Pythio, between Didymoteicho and Orestiada, the line to Istanbul branches off. It reaches Ormenio, the current terminus of all passenger services, shortly before crossing the Bulgarian border and continuing to Svilengrad, where it joins the railway from Sofia to Istanbul.

History

The section between Alexandroupoli (formerly Dedeagatch) and Svilengrad was opened in 1874 by the Chemins de fer Orientaux (CO) when the entire Thrace was part of the Ottoman Empire. The part between Pythio and Svilengrad was part of the CO main line from Istanbul to western Europe. After World War I and the subsequent Greek-Turkish War from 1919 to 1922, and finally peace in the form of the Lausanne treaty, the Chemins de fer Orientaux (CO) ended up having a network straddling Turkey and Greece. This created operational difficulties, each country having now its own set of rules and regulations, currencies, and languages. In order to resolve this situation, the CO decided to split itself into two companies: one for the Greek part, one for the Turkish part of the railway.[4]

After the Treaty of Lausanne was signed in 1923 and the borders between Greece and Turkey were drawn, the line was in Greek territory with the exception of a 10 km (6.2 mi) long section from Nea Vyssa to Marasia via Karaağaç that was in Turkey. In order to get from Alexandroupoli to Dikaia, Ormenio and Svilengrad in Bulgaria, trains of the French-Hellenic Railway Company (Chemin de fer Franco-Hellenique) and later of the Hellenic State Railways would travel through Turkish territory. Trains stopped at Karaağaç, which in Greek timetables was listed as Αδριανούπολις (Adrianoupolis)/Edirne.

The CO created the "Companie franco-hellenique des chemins de fer" (CFFH) as a subsidiary company. The CFFH was incorporated in July 1929 as a French company and its headquarters was located in Paris. The CO transferred to the CFFH the Greek part of its line from Alexandroupoli to Svilengrad, except for a short section of about 10 km[5] in Turkey serving Edirne Karaagaç station and for about 3 km between the Greek border and Svilengrad station in Bulgaria.[6] Overall, this line was 165 km[7] long route from the Aegean Sea port city Alexandroupoli to Ormenio the last station in Greece before entering Bulgaria. Pythion station was the junction towards Turkey. Along with the infrastructure, the CO transferred also some motive power and rolling stock to the CFFH. The CFFH stock was transferred to CO shareholders on the basis of 1 CFFH stock for every 5 CO stock.[8] These CFFH stock started trading on the market in July 1931.

Regarding the Edirne Karaagaç railway enclave so to speak, the CO retained operating rights over the section Svilengrad to Pythion to be able to reach Edirne and even Svilengrad. On the other hand, the CFFH retained operating rights through the Edirne section of the line to access the Greek part of the line past Edirne, through to Svilengrad. When the Turkish part of the CO was sold to the Turkish railways, these operating rights were also sold, enabling TCDD to reach Edirne with its own motive power, albeit with a CFFH driver. Likewise, when Greek State Railways (SEK) took over from the CFFH, they kept the operating right through Edirne Karaagaç. Operational working was facilitated by a provision in the Lausanne treaty allowing for trains to cross the borders in and out of Karaagaç without border control not custom taxes.[9] These rights survived until 1971 when TCDD inaugurated its own line from Pehlivanköy to Edirne & Svilengrad fully on Turkish territory.

At the same time, in 1971, SEK designed and constructed a 9 km (5.6 mi) direct connection between Nea Vyssa and Marasia within the Greek borders, thus avoiding Turkish territory and bypassing Karaağaç and with a new intermediate station at Kastanies. The new passing loop section, which includes a new bridge over the river Ardas is still in use.[10] The former CO station in Edirne Karaağaç, west of the Maritsa, was not no longer served by either TCDD or by SEK and went into disuse. The tracks lifted and the building converted to other use.

The CFFH was the only railway connecting Turkey to Europe and enjoyed the related traffic and revenue. Some prestigious trains like the Orient Express transited on CFFH network. Otherwise, the CFFH did not generate any major traffic, either freight or passengers along its line. During the Greek Civil War until 1949, the trains operated only by daylight and were supplemented with empty freight cars in front of the locomotive and armed with escort to protect them from mines. SEK took over operations of the line and rolling stock, effective 1 January 1955, and CFFH ceased.

In 2020 it was announced that section of line between Pythio and Ormenio was to be upgraded, at a cost of €1.4m as part of an ambitious integrated intergovernmental transport plan which will see this, and 39 other transport sector projects be built, with financing from the European Commission with a total of €117 million.[11][12] The package of measures aims to build or improve transport connections and connectivity across Europe, with a focus on sustainable transport. The project at the Pythian-Ormenio section envisions upgrading the existing line and the construction of a second one, with the aim of improving freight transport with Bulgaria and Turkey.[13]

Main stations

The stations on the Alexandroupoli–Svilengrad railway are:

Services

As of 2020, the Alexandroupoli–Svilengrad railway is only used by four daily pairs of local trains Alexandroupoli–Ormenio, two of which are express services.[14]

References

- "OSE - 2017 Network Statement Annexes". p. 5.

- Greece severs international links, International Railway Journal, March, 2011

- https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/rail-nip/nip-ccs-tsi-bulgaria-en.pdf

- Le Journal des finances, Paris, 27 December 1929 (in French)

- Moden measurement done on www.Openstreetmap.com indicate 10.2 km

- Le Journal des chemins de fer, des mines et des TP, Paris, 29 March 1930 (in French)

- See Alexandroupoli–Svilengrad railway. The railway is 178.5 km long minus 10 km in Turkey and 3 km in Bulgaria

- Le Journal des débats, 10 March 1931 (in French)

- Traité de paix entre les puissances alliées et la Turquie, Lausanne, 1923. Article n°107

- I. Zartaloudis; D. Karatolos; D. Koutelidis; G. Nathenas; S. Fasoulas; A. Filippoupolitis (1997). Οι Ελληνικοί Σιδηρόδρομοι (Hellenic Railways) (in Greek). Μίλητος (Militos). p. 126. ISBN 960-8460-07-7.

- http://v4.deltatv.gr/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=25313:αναβαθμίζεται-η-σιδηροδρομική-γραμμή-ορμενίου-πυθίου&Itemid=213

- "Studies for upgrading and doubling the railway line from Pythio to Ormenio". European Commission. Innovation and Networks Executive Agency. May 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) 2019 TRANSPORT CALL Proposal for the selection of projects - Studies for upgrading and duplicating the railway line from Pythio to Ormenio" (pdf). European Commission. Innovation and Networks Executive Agency. September 2019. p. 29. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- https://www.radioevros.gr/ksekinoun-ksana-ta-dromologia-trenou-aleksandroupoli-ormenio-aleksandroupoli/