Aeta people

The Aeta (Ayta /ˈaɪtə/ EYE-tə; Kapampangan: áitâ), or Agta, are an indigenous people who live in scattered, isolated mountainous parts of the island of Luzon, the Philippines.

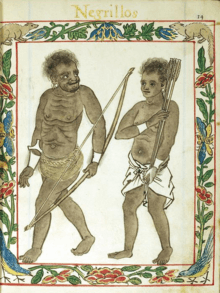

These people are considered to be Negritos, whose skin ranges from dark to very dark brown, and possessing features such as a small stature and frame; hair of a curly to kinky texture and a higher frequency of naturally lighter colour (blondism) relative to the general population, small nose, and dark brown eyes. They are thought to be among the earliest inhabitants of the Philippines, preceding the Austronesian migrations.[1]

The Aeta were included in the group of people named "Negrito" during the Spanish Era. Various Aeta groups in northern Luzon are named Pugut or Pugot, an Ilocano term that also means "goblin" or "forest spirit",[2] and is the colloquial term for people with darker complexions.

As nomadic people, Aeta communities typically consist of approximately 1 to 5 families of mobile group.[3] So the word Aeta or Agta is frequently used as an umbrella term for numerous Aeta groups in the Philippines, considering their varied locations in Luzon, including some living in parts of Visayas and Mindanao. Groups under the “Aeta” umbrella are normally referred to after their demographic locations. Scholars (particularly anthropologists and ethnographers) focusing on the Aeta communities tend to follow this particular naming to also account for cultural variations (most notably, in language) for each individual group. Aeta of Magbukun (also called Aeta of Bataan),[4] Casiguran Dumagat Agta, Aeta of Zambales (also called Aeta of Mt. Pinatubo), Aeta of San Mariano Isabela,[5] and Agta of Lamika,[6] are some of the Aeta communities in the Philippine archipelago.

History

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Aeta people in the Philippines are often grouped with other Negritos, such as the Semang on the Malay Peninsula, and sometimes grouped with Australo-Melanesians, which includes groups such as the natives of Australia; Papuans; and the Melanesians of the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and the French overseas special collectivity of New Caledonia.

The history of the Aetas continues to confound anthropologists and archaeologists. One theory suggests that the Aeta are the descendants of the original inhabitants of the Philippines, who, contrary to their seafaring Austronesian neighbors, arrived through land bridges that linked the islands with the Asian mainland. Unlike many of their Austronesian counterparts, the Aetas have shown resistance to change. Aetas had little interaction with the Spaniards as they remained in the mountains during the Spanish rule. Even the attempts of the Spaniards failed to settle them in reducciones or reservations all throughout Spanish rule. According to Spanish observers like Miguel López de Legazpi, Negritos possessed iron tools and weapons. Their speed and accuracy with a bow and arrow were proverbial and they were fearsome warriors. Unwary travelers or field workers were often easy targets. Despite their martial prowess, however, the Aeta's small numbers, primitive economy and lack of organization often made them easy prey for better-organized groups. Zambals seeking people to enslave would often take advantage of their internal feuding. They were often enslaved and sold to Borneo and China, and, unlike the serf feudal system imposed on other Filipinos, there was little chance of manumission.[7]

Demographics

In 2010, there were 50,236 Aeta people in the Philippines.[8]

Ancestral lands

Aetas are found in Zambales, Tarlac, Pampanga, Panay, Bataan, and Nueva Ecija, but were forced to move to resettlement areas in Pampanga and Tarlac following the devastating Mount Pinatubo eruption in June 1991.[9]

Some Aeta communities have received government land titles recognizing their claims to their ancestral lands.

A total of 454 Aeta families in Floridablanca, Pampanga, received their Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) on May 27, 2009. The title covers 7,440.10 hectares in San Marcelino and Brgy. Batiawan in Zambales and barangays Mawakat and Nabuklod in Floridablanca.[10] It was the first time clean ancestral domain titles were distributed by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples.

The Aeta Abellen community of Sitio Maporac, Barangay New San Juan, Cabangan, Zambales, received the first Philippine’s first Certificate of Ancestral Domain Claim (CADC) on March 8, 1996. The CADT was acquired 16 years later in December 2010.[11]

Lifestyle

The Aeta are nomadic and build only temporary shelters made of sticks driven to the ground and covered with the palm of banana leaves. The more modernized Aetas have moved to villages and areas of cleared mountains. They live in houses made of bamboo and cogon grass.

Mining, deforestation, illegal logging, and slash-and-burn farming have caused the indigenous population in the country to steadily decrease to the point where they number only in the thousands today. The Philippine government affords them little or no protection, and the Aeta have become extremely nomadic due to social and economic strain on their culture and way of life that had previously remained unchanged for thousands of years.

As hunter-gatherers, adaptation plays an important role in Aeta communities to survive. This often includes gaining knowledge about the tropical forest that they live in, the typhoon cycles that travel through their area, and other seasonal weather changes that affect the behavior of the flora and fauna in their location.[12] Another important survival skill is storytelling. Like many other hunter-gatherer societies, the Aeta promote social values, such as cooperation, through stories. Thus, they highly value skilled storytellers.[13]

Dry season for many Aeta communities means intense work. They not only hunt and fish more, the start of the dry season also means swiddening the land for future harvest. While the clearing of land is done by both men and women, Aeta women tend to do most of the harvesting. During this period, they also do business transactions with non-Aeta communities living around the vicinity they temporarily settled in either to sell the food they gathered, or to work as temporary farmers or field laborers. Aeta women play more active roles in business transactions with non-Aeta communities, mostly as traders and agricultural workers for lowland farmers.[14] While dry season typically means bountiful food for Aetas, rainy season (which often falls in the Philippines between September and December) often provides the opposite experience, considering the difficulties of traversing flooded and wet forests for hunting and gathering.

Aeta communities use different tools in their hunting and gathering activities. Traditional tools include traps, knives, and bow and arrow, with different types of arrow points for specialized purposes.[6] Most Aetas are trained for hunting and gathering at age 15, including Aeta women. While men and some women typically use the standard bow and arrow, most Aeta women prefer knives and often hunt with their dogs and in groups to increase efficiency and for social reasons.[15] Fishing and food gathering are also done by both males and females. In terms of gender, then, Aeta communities are more egalitarian in structure and in practice.

Language

All Aeta communities have adopted the language of their Austronesian Filipino neighbors, which have sometimes diverged over time to become different languages.[16] These include, in order of number of speakers, Mag-indi, Mag-antsi, Abellen, Ambala, and Mariveleño.

Religion

Indigenous monotheistic religion

There are different views on the dominant character of the Aeta religion. Those who believe they are monotheistic argue that various Aeta tribes believe in a supreme being who rules over lesser spirits or deities, with the Aeta of Mt. Pinatubo worshipping "Apo Na". The Aetas are also animists. For example, the Pinatubo Aeta believe in environmental spirits. They believe that good and evil spirits inhabit the environment, such as the spirits of the river, sea, sky, mountain, hill, valley and other places.

No special occasion is needed for the Aeta to pray, but there is a clear link between prayer and economic activities. The Aeta dance before and after a pig hunt. The night before Aeta women gather shellfish, they perform a dance which is partly an apology to the fish and partly a charm to ensure the catch. Similarly, the men hold a bee dance before and after the expeditions for honey.

Indigenous polytheistic religion

There are four manifestations of the "great creator" who rules the world: Tigbalog is the source of life and action; Lueve takes care of production and growth; Amas moves people to pity, love, unity, and peace of heart; while Binangewan is responsible for change, sickness, and death.

- Gutugutumakkan – The Supreme Being and Great Creator who have four manifestations, namely, Tigbalog, Lueve, Amas, and Binangewan.

- Kedes - The god of the hunt.

- Pawi - The god of the forest.

- Sedsed - The god of the sea.

Colonial religion

In the mid-1960s, missionaries of the American-based Evangelical Protestant mission group New Tribes Mission, in their effort to reach every Philippine tribal group with the Christian Gospel, reached out to the Agtas/Aetas. The mission agency provided education, including pastoral training for natives to reach members of their own tribe. Today, a large percentage of Agtas/Aetas of Zambales and Pampanga are Evangelicals.[17] Jehovah's Witnesses also have members of the Aeta people. (See 1993 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses)

Clothing

Their traditional clothing is very plain. The young women wear wrap around skirts. Elder women wear bark cloth, while elder men wear loin cloths. The old women of the Agta wear a bark cloth strip which passes between the legs, and is attached to a string around the waist. Today, most Aeta who have been in contact with lowlanders have adopted the T-shirts, pants and rubber sandals commonly used by the latter.

Practices

The Aetas are skillful in weaving and plaiting. Women exclusively weave winnows and mats. Only men make armlets. They also produce raincoats made of palm leaves whose bases surround the neck of the wearer, and whose topmost part spreads like a fan all around the body.

According to one study, "About 85% of Philippine Aeta women hunt, and they hunt the same quarry as men. Aeta women hunt in groups and with dogs, and have a 31% success rate as opposed to 17% for men. Their rates are even better when they combine forces with men: mixed hunting groups have a full 41% success rate among the Aeta."[18]

Medicine

Aeta women are known around the country as experts of the herbal medicines.

Among the Aeta community in Ilagan, Isabela for example, banana leaves are used to cure toothache. They also bathe themselves with cooled-down water boiled with camphor leaves (subusob) to help alleviate fever, or they make herbal teas out of the camphor leaves that they then drink thrice a day if the fever and cold still persist. For muscle pains, they drink herbal teas extracted from kalulong leaves and have the patient take it thrice a day. In order to prevent relapse after giving birth, women also bathe themselves in cooled-down water boiled with sahagubit roots. The drinking of sahagubit herbal tea is likewise recommended to deworm Aeta children, or generally to alleviate stomachache. For birth control purposes, Aeta women drink wine made out of lukban (pamelo) root. They are, however, not advised to drink herbal tea from makahiya extract even if it's also used to elevate stomachache problems due to the belief that it will cause abortion. The idea behind this is that like the closing of makahiya leaves once touched, the womb may also close once the makahiya touches it. The Aeta in Isabela also recommend drinking herbal tea out of wormwood (herbaca) leaves or stem to address women's irregular menstrual cycle. They take herbal teas from lemon grass (barbaraniw) extract thrice a day to normalize blood pressure.[19]

If the illness persists even after continuous drinking of recommended herbal medicine, that's when they seek the help of an herbolario (or soothsayer). They do so because the Aeta believe that their illnesses are caused by a spirit that they may have offended, in which case herbal medicines or medical doctors won't be able to address. In order to appease the spirits, they ask the herbolario to perform a ritual called ud- udung. In this ritual, the herbolario places rice or raw eggs on the patient's forehead first to determine what causes the illness and repeats this several times to confirm. After the herbolario is satisfied, the patient will be asked to bathe with ricewash, and then to offer food to appease the offended spirit.[20]

The Aeta communities take pride in their use of herbal medicines and their own natural ways of curing the sick. Finding their main source of herbal medicines in their habitat rather than buying costly medicines, emphasizing the mutual relationship with the nature, also has a great attitudinal impact pertaining to sustainability approach and practices in healthcare.[20]

Art

A traditional form of visual art is body scarification. The Aetas intentionally wound the skin on their back, arms, breast, legs, hands, calves and abdomen, and then they irritate the wounds with fire, lime and other means to form scars.

Other "decorative disfigurements" include the chipping of the teeth. With the use of a file, the Dumagat modify their teeth during late puberty. The teeth are dyed black a few years afterwards.

The Aetas generally use ornaments typical of people living in subsistence economies. Flowers and leaves are used as earplugs for certain occasions. Girdles, necklaces, and neckbands of braided rattan incorporated with wild pig bristles are frequently worn.

Music

The Aeta have a musical heritage consisting of various types of agung ensembles, ensembles composed of large hanging, suspended or held, bossed/knobbed gongs, which act as drone, without any accompanying melodic instrument.

Traditional political organization

While the father is normally the figurehead of the family, Aeta communities or bands traditionally had anarchic political structure wherein they don't have appointed chiefs to exercise authority over them. Individual Aeta is on equal grounds with the other and their main course of social interaction is through their tradition. It's also the tradition, and not constituted laws, that maintain the equality among them and guide their way of life. They do have group of elders in their community, called pisen, who they tend to go to when it comes to arbitrating decisions. However, the decisions made by the elders only remain in advisory capacity and no one could force any individual to follow those decisions. Their guiding principle and conflict resolution is through a sustained deliberation.[21]

Overtime, this egalitarian political structure was disturbed due to recurring contacts with the lowland Filipinos wherein the local officials and individuals they interact with forced Aeta communities to create government structure resembling those in the lowlands. At times, Aeta communities do organize themselves in government-like system with a Capitan (Captain), Conseyal (Council) and Policia (Police). But mostly, they resist such imposed organization. In particular, they refuse to appoint a chief (or a president) that will govern them although they do have one elder that takes the responsibility of leadership. This informal kind of government can also be found in their judicial process. When someone in their community did something wrong, they would deliberate about it but more importantly, they don't talk about what kind of punishment they will hand to the wrong-doer but instead the deliberation is about understanding the motivation behind the action and prevent the consequence of the action from developing into something worse. Young men and women are excluded from the deliberation process. In this particular case, women are also largely excluded from the deliberation process even when they are allowed to attend the hearing or even when sometimes they can make their opinion about the problem. For the most part, women are not given room within the decision making process because the Aeta communities also follow a strict gender role were women are mostly expected take care of the children and the husband.[21]

See also

References

- "The Aeta". peoplesoftheworld.org.

- Thomas N. Headland; John D. Early (Mar 1, 1998). Population Dynamics of a Philippine Rain Forest People: The San Ildefonso Agta. University Press of Florida. p. 208. ISBN 9780813015552.

- Allingham, R. Rand (December 2008). "Assessment of Visual Status of the Aeta, a Hunter-Gatherer Population of the Philippines (An AOS Thesis)". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 106: 240–251. ISSN 0065-9533. PMC 2646443. PMID 19277240.

- Balilla, Vincent S.; Anwar McHenry, Julia; McHenry, Mark P.; Parkinson, Riva Marris; Banal, Danilo T. (2013). "Indigenous Aeta Magbukún Self-Identity, Sociopolitical Structures, and Self-Determination at the Local Level in the Philippines". Journal of Anthropology. 2013: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2013/391878. ISSN 2090-4045.

- Rai, Navin K (1989). From forest to field: a study of Philippine Negrito foragers in transition (Thesis). Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms. OCLC 416933818.

- Griffin, P. Bion (2001). "A Small Exhibit on the Agta and Their Future". American Anthropologist. 103 (2): 515–518. doi:10.1525/aa.2001.103.2.515. ISSN 1548-1433.

- Scott, William (1994). Barangay. Manila, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila. pp. 252–256.

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues: Republic of the Philippines. International Fund For Agricultural Development. November 2012.

- Teves, Ma Althea (May 31, 2009). "First clean ancestral domain title for Aetas awarded". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "Explore Case Studies: Maalagay Dogal/Matilo, Philippines". ICCA Registry. March 2013. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Griffin, P. Bion. Griffin, Agnes Estioko- (1985). The Agta of northeastern Luzon : recent studies. University of San Carlos. OCLC 760167711.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Smith, Daniel; Schlaepfer, Philip; Major, Katie; Dyble, Mark; Page, Abigail E.; Thompson, James; et al. (5 December 2017). "Cooperation and the evolution of hunter-gatherer storytelling". Nature Communications. 8. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02036-8. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5717173. PMID 29208949.

- "Agta Forager Women in the Philippines". www.culturalsurvival.org. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Goodman, Madeleine J.; Griffin, P. Bion; Estioko-Griffin, Agnes A.; Grove, John S. (June 1985). "The compatibility of hunting and mothering among the agta hunter-gatherers of the Philippines". Sex Roles. 12 (11–12): 1199–1209. doi:10.1007/bf00287829. ISSN 0360-0025.

- Reid, Lawrence. 1987. "The early switch hypothesis". Man and Culture in Oceania, 3 Special Issue: 41-59.

- "37 NEW AETA BELIEVERS BAPTIZED IN THE PHILIPPINES". Asia Harvest. 11 November 2008.

- Dahlberg, Frances (1975). Woman the Gatherer. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02989-6.

- Modern psychology and ancient wisdom : psychological healing practices from the world's religious traditions. Mijares, Sharon G. (Sharon Grace), 1942- (Second ed.). New York. 2015-09-11. ISBN 9781138884502. OCLC 904506046.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Mijares, Sharon Grace, 1942- (2015-09-11). Modern psychology and ancient wisdom : psychological healing practices from the world's religious traditions. ISBN 978-1138884502. OCLC 1048748475.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Noval-Morales, Daisy; Monan, James (1979). A Primer on The Negrito of The Philippines. Manila, Philippines: Philippine Business for Social Progress.