Adrian Willaert

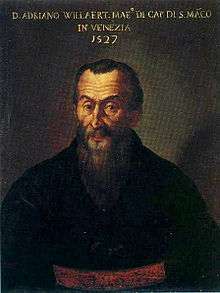

Adrian Willaert (c. 1490 – 7 December 1562) was a Netherlandish composer of the Renaissance and founder of the Venetian School. [1] He was one of the most representative members of the generation of northern composers who moved to Italy and transplanted the polyphonic Franco-Flemish style there.[2]

Life

He was born at Rumbeke near Roeselare. According to his student, the renowned 16th century music theorist Gioseffo Zarlino, Willaert went to Paris first to study law, but instead decided to study music. In Paris he met Jean Mouton, the principal composer of the French royal chapel and stylistic compatriot of Josquin des Prez, and studied with him.

Sometime around 1515 Willaert first went to Rome. An anecdote survives that indicates the musical ability of the young composer: Willaert was surprised to discover the choir of the papal chapel singing one of his own compositions, most likely the six-part motet Verbum bonum et suave, and even more surprised to learn that they thought it had been written by the much more famous composer Josquin. When he informed the singers of their error – that he was in fact the composer – they refused to sing it again. Indeed, Willaert's early style is very similar to that of Josquin, with smooth polyphony, balanced voices and frequent use of imitation or strict canon. Indeed, the early Willaert admired Josquin so much that he wrote a mass, Missa Mente Tota, in double canon throughout with two free voices, based upon a movement of a famous Josquin motet (Vultum tuum deprecabuntur).

In July 1515, Willaert entered the service of Cardinal Ippolito I d'Este of Ferrara. Ippolito was a traveler, and Willaert likely accompanied him to various places, including Hungary, where he likely resided from 1517 to 1519. When Ippolito died in 1520, Willaert entered the service of Duke Alfonso of Ferrara. In 1522 Willaert had a post at the court chapel of Duke Alfonso; he remained there until 1525, at which time records show he was in the employ of Ippolito II d'Este in Milan.

Willaert's most significant appointment, and one of the most significant in the musical history of the Renaissance, was his selection as maestro di cappella of St. Mark's at Venice. Music had languished there under his predecessor, Pietro de Fossis (1491–1525), but that was shortly to change. The Venetian Doge Andrea Gritti had a rather large hand in Willaert's appointment to the position of maestro di cappella at St. Mark's.[3]

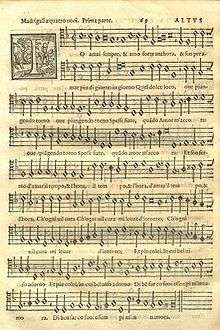

From his appointment in 1527 until his death in 1562, he retained the post at St. Mark's.[4] Composers came from all over Europe to study with him, and his standards were high both for singing and composition. During his previous employment with the dukes of Ferrara, he had acquired numerous contacts and influential friends elsewhere in Europe, including the Sforza family in Milan; doubtless this assisted in the spread of his reputation, and the consequent importation of musicians from foreign countries into northern Italy. In Ferrarese court documents, Willaert is referred to as "Adriano Cantore".[5] In addition to his output of sacred music as the director of St. Mark's, he wrote numerous madrigals, a secular form; he is considered a Flemish madrigal composer of the first rank.[6]

Musical style and influence

Willaert was one of the most versatile composers of the Renaissance, writing music in almost every extant style and form. In force of personality, and with his central position as maestro di cappella at St. Mark's, he became the most influential musician in Europe between the death of Josquin and the time of Palestrina.[7] Some of Willaert's motets and chanzoni franciose a quarto sopra doi (double canonic chansons) had been published as early as 1520 in Venice.[8] Willaert owes much of his fame in sacred music to his motets.[9]

According to Gioseffo Zarlino, writing later in the 16th century, Willaert was the inventor of the antiphonal style from which the polychoral style of the Venetian school evolved. As there were two choir lofts – one to each side of the main altar of St. Mark's, both provided with an organ —, Willaert divided the choral body into two sections, using them either antiphonally or simultaneously. De Rore, Zarlino, Andrea Gabrieli, Donato, and Croce, Willaert's successors, all cultivated this style.[10] The tradition of writing that Willaert established during his time at St. Mark's was continued by other composers working there throughout the 17th century.[3] He then composed and performed psalms and other works for two alternating choirs. This innovation met with instantaneous success and strongly influenced the development of the new method.[4] In Venice, a compositional style, established by Willaert, for multiple choirs dominated.[10] In 1550 he published Salmi spezzati, antiphonal settings of the psalms, the first polychoral work of the Venetian school. Willaert's work in the religious genre established Flemish techniques firmly as an important part of the Venetian Style.[11] While more recent research has shown that Willaert was not the first to use this antiphonal, or polychoral method — Dominique Phinot had employed it before Willaert, and Johannes Martini even used it in the late 15th century – Willaert's polychoral settings were the first to become famous and widely imitated.[12]

With his contemporaries, Willaert developed the canzone (a form of polyphonic secular song) and ricercare, which were forerunners of modern instrumental forms.[13] Willaert also arranged 22 four-part madrigals for voice and lute written by Verdelot.[14] In an early 4-part vocal work, Quid non-ebrietas? (In some sources called the Chromatic Duo) Willaert uses musica ficta around the circle of 5ths in one of the voices resulting in an augmented 7th in unison with the ending octave, an outstanding experiment with chromatic enharmonicism. Willaert was among the first to extensively use chromaticism in the madrigal.[15] Looking forward, we are given an image of early word painting in his madrigal Mentre che'l cor.[16] Willaert, who was fond of the older compositional techniques such as the canon, often placed the melody in the tenor of his compositions, treating it as a cantus firmus.[17] Willaert, with the help of De Rore, standardized a five-voice setting in madrigal composition.[17] Willaert also pioneered a style that continued until the end of the madrigal period of reflecting the emotional qualities of the text and the meanings of important words as sharply and clearly as possible.[15]

Willaert was no less distinguished as a teacher than as a composer.[9] Among his disciples were Cipriano de Rore, his successor at St. Mark's; Costanzo Porta; the Ferrarese Francesco Viola; Gioseffo Zarlino; and Andrea Gabrieli. Another composer stylistically descended from Willaert was Lassus.[6] These composers, except for Lassus, formed the core of what came to be known as the Venetian school, which was decisively influential on the stylistic change that marked the beginning of the Baroque era. Among Willaert's pupils in Venice, one of the most prominent was his fellow northerner Cipriano de Rore.[18] The Venetian School flourished for the rest of the 16th century, and into the 17th, led by the Gabrielis and others.[4] Willaert also probably influenced a young Palestrina.[6] Willaert left a large number of compositions – 8 (or possibly 10) masses, over 50 hymns and psalms, over 150 motets, about 60 French chansons, over 70 Italian madrigals and 17 instrumental (ricercares).

Notes

- Miller, Hugh M. (1972). History of Music. New York: Harper & Rowe, Publishers, Inc. p. 53.

- Reese, Gustave (1959). Music in the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc. pp. 370–371.

- Fenlon, Iain, ed. (1989). The Renaissance From the 1470s to the end of the 16th century. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. pp. 111–112.

- World of Music An Illustrated Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Abradale Press. 1963. p. 1484. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Lockwood, Lewis; Giulio, Giulio (2001). "Adrian Willaert 1. Early career and Ferrarese service.". In Root, Deane L. (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Oxford University Press.

DB1

- Wooldridge, H. E. (1973). The Oxford History of Music. 2. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, Inc. p. 197.

- Reese, Gustave (1959). Music in the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc. p. 348.

- Abraham, Gerald (1917). The Concise Oxford History of Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 230.

- Reese, Gustave (1959). Music in the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc. p. 371.

- Einstein, Alfred (1965). A Short History of Music. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 67.

- Robertson, Alec; Stevens, Denis, eds. (1965). A History of Music. 2. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 160.

- Fenlon, Iain, ed. (1989). The Renaissance From the 1470s to the end of the 16th century. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. p. 114.

- World of Music An Illustrated Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Abradale Press. 1963. p. 1485. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Abraham, Gerald (1917). The Concise Oxford History of Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 228–229.

- Robertson, Alec; Stevens, Denis, eds. (1965). A History of Music. 2. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 149.

- Reese, Gustave (1959). Music in the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc. p. 324.

- Ulrich, Homer; Pisk, Paul A. (1963). A History of Music and Musical Style. New York: Harcourt, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. p. 177.

- Reese, Gustave (1959). Music in the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc. p. 310.

References and further reading

- Article "Adrian Willaert," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. 20 vol. London, Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1980. ISBN 1-56159-174-2

- Gustave Reese, Music in the Renaissance. New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1954. ISBN 0-393-09530-4

- Harold Gleason and Warren Becker, Music in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Music Literature Outlines Series I). Bloomington, Indiana. Frangipani Press, 1986. ISBN 0-89917-034-X

- Kidger, David M. Adrian Willaert: a guide to research Routledge ISBN 0-8153-3962-3 ISBN 978-0-8153-3962-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adrian Willaert. |

- Adriaan Willaert at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Adrian Willaert at HOASM

- Free scores by Adrian Willaert at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free access to high-resolution images of manuscripts containing works by this composer from Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music

- Free scores by Adrian Willaert in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Listen to free recordings of songs from Umeå Akademiska Kör.

- The Academy of Musical and Theatrical Arts Adriaen Willaert in Roeselare (Belgium) was named after Adrian Willaert.