Acer platanoides

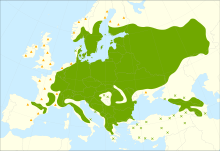

Acer platanoides, also called the Emerald Queen Maple or the Norway Maple, is a species of maple native to eastern and central Europe and western Asia, from France east to Russia, north to southern Scandinavia and southeast to northern Iran.[2][3][4] It was brought to North America in the mid-1700s as a shade tree.[5] It is a member of the family Sapindaceae.

| Norway maple | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Norway maple leaves | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Sapindaceae |

| Genus: | Acer |

| Section: | Acer sect. Platanoidea |

| Species: | A. platanoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Acer platanoides | |

| |

| Distribution map (native habitat) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Description

Acer platanoides is a deciduous tree, growing to 20–30 m (65–100 ft) tall with a trunk up to 1.5 m (5 ft) in diameter, and a broad, rounded crown. The bark is grey-brown and shallowly grooved. Unlike many other maples, mature trees do not tend to develop a shaggy bark. The shoots are green at first, soon becoming pale brown. The winter buds are shiny red-brown.

The leaves are opposite, palmately lobed with five lobes, 7–14 cm (2 3⁄4–5 1⁄2 in) long and 8–20 cm or 3 1⁄4–7 3⁄4 in (rarely 25 cm or 9 3⁄4 in) across; the lobes each bear one to three side teeth, and an otherwise smooth margin. The leaf petiole is 8–20 cm (3 1⁄4–7 3⁄4 in) long, and secretes a milky juice when broken. The autumn colour is usually yellow, occasionally orange-red.[6][7][8]

The flowers are in corymbs of 15–30 together, yellow to yellow-green with five sepals and five petals 3–4 mm (0–1⁄4 in) long; flowering occurs in early spring before the new leaves emerge. The fruit is a double samara ![]()

Under ideal conditions in its native range, Norway maple may live up to 250 years, but often has a much shorter life expectancy; in North America, for example, sometimes only 60 years. Especially when used on streets, it can have insufficient space for its root network and is prone to the roots wrapping around themselves, girdling and killing the tree. In addition, their roots tend to be quite shallow and thereby they easily out-compete nearby plants for nutrient uptake.[9] Norway maples often cause significant damage and cleanup costs for municipalities and homeowners when branches break off in storms as it does not have strong wood.[10][11]

Classification and identification

The Norway maple is a member (and is the type species) of the section Platanoidea Pax, characterised by flattened, disc-shaped seeds and the shoots and leaves containing milky sap. Other related species in this section include Acer campestre (field maple), Acer cappadocicum (Cappadocian maple), Acer lobelii (Lobel's maple), and Acer truncatum (Shandong maple). From the field maple, the Norway maple is distinguished by its larger leaves with pointed, not blunt, lobes, and from the other species by the presence of one or more teeth on all of the lobes.[10][11]

It is also frequently confused with the more distantly related Acer saccharum (sugar maple). The sugar maple is easy to differentiate by clear sap in the petiole (leaf stem); Norway maple petioles have white sap. The tips of the points on Norway maple leaves reduce to a fine "hair", while the tips of the points on sugar maple leaves are, on close inspection, rounded. On mature trees, sugar maple bark is more shaggy, while Norway maple bark has small, often criss-crossing grooves. While the shape and angle of leaf lobes vary somewhat within all maple species, the leaf lobes of Norway maple tend to have a more triangular shape, in contrast to the more squarish lobes often seen on sugar maples. Flowering and seed production begins at ten years of age, however large quantities of seeds are not produced until the tree is 20. As with most maples, Norway maple is normally dioecious (separate male and female trees), occasionally monoecious, and trees may change gender from year to year.

The fruits of Norway maple are paired samaras with widely diverging wings,[12]:372 distinguishing them from those of sycamore, Acer pseudoplatanus which are at 90 degrees to each other.[12] Norway maple seeds are flattened, while those of sugar maple are globose. The sugar maple usually has a brighter orange autumn color, where the Norway maple is usually yellow, although some of the red-leaved cultivars appear more orange.

The flowers emerge in spring before the leaves and last 2-3 weeks. Leafout of Norway Maple is tied to photoperiod and initiated when day lengths reach approximately 13 hours, which is generally in April. Leaf drop in autumn is initiated when day lengths fall to approximately 10 hours. Depending on the latitude, leaf drop may vary by as much as three weeks, beginning in the second week of October in Scandinavia and the first week of November in southern Europe. Unlike some other maples that wait for the soil to warm up, A. platanoides seeds require only three months of exposure to temperatures lower than 4 °C (40 °F) and will sprout in early spring, around the same time that leafout begins. Norway maple does not require freezing temperatures for proper growth, however it is adapted to higher latitudes with long summer days and does not perform well when planted south of the 37th parallel, the approximate southern limit of its range in Europe. The heavy seed crop and high germination rate contributes to its invasiveness in North America, where it forms dense monotypic stands that choke out native vegetation. Since Norway Maple's leafout in spring is also tied to photoperiod unlike most North American trees which leaf out based on air temperature, the tree has a competitive advantage in that it may leaf out well before native trees and shrubs since the latter may be delayed by the weather conditions. It is one of the few introduced species that can successfully invade and colonize a virgin forest. By comparison, in its native range, Norway maple is rarely a dominant species and instead occurs mostly as a scattered understory tree.[10][11]

Cultivation and uses

The wood is hard, yellowish-white to pale reddish, with the heartwood not distinct; it is used for furniture and turnery.[13] Norway maple sits ambiguously between hard and soft maple with a Janka hardness of 1,010 lbf or 4,500 N. The wood is rated as non-durable to perishable in regard to decay resistance.[14] In Europe, it is used for furniture, flooring and musical instruments. This species as grown in the former Yugoslavia is also called Bosnian Maple, and is probably the Maple used by the famous Italian violin makers, Stradivari and Guarneri.

Norway maple has been widely taken into cultivation in other areas, including western Europe northwest of its native range. It grows north of the Arctic Circle at Tromsø, Norway. In North America, it is planted as a street and shade tree as far north as Anchorage, Alaska.[15] It is most recommended in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 7 but will grow in warmer zones (at least up to Zone 10) where summer heat is moderate, as along the Pacific coast south to the Los Angeles basin.[16] During the 1950s–60s it became popular as a street tree due to the large-scale loss of American elms from Dutch elm disease.

It is favored due to its tall trunk and tolerance of poor, compacted soils and urban pollution, conditions in which sugar maple has difficulty. It has become a popular species for bonsai in Europe and is used for medium to large bonsai sizes and a multitude of styles.[17] Norway maples are not typically cultivated for maple syrup production due to the lower sugar content of the sap compared to sugar maple.[18]

Cultivars

Many cultivars have been selected for distinctive leaf shapes or colorations, such as the dark purple of 'Crimson King' and 'Schwedleri', the variegated leaves of 'Drummondii', the light green of 'Emerald Queen', and the deeply divided, feathery leaves of 'Dissectum' and 'Lorbergii'. The purple-foliage cultivars have orange to red autumn colour. 'Columnare' is selected for its narrow upright growth.[11][19] The cultivars 'Crimson King'[20] and Princeton Gold='Prigold'[21] have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.

As an invasive species in North America

The Norway maple was introduced to northeastern North America between 1750 and 1760 as an ornamental shade tree. It was brought to the Pacific Northwest in the 1870s.[5] The roots of Norway maples grow very close to the ground surface, starving other plants of moisture. For example, lawn grass (and even weeds) will usually not grow well beneath a Norway maple, but English Ivy, with its minimal rooting needs, may thrive. In addition, the dense canopy of Norway maples can inhibit understory growth.[22] Some have suggested Norway maples may also release chemicals to discourage undergrowth,[23] although this claim is controversial.[22] A. platanoides has been shown to inhibit the growth of native saplings as a canopy tree or as a sapling.[22] The Norway maple also suffers less herbivory than the sugar maple, allowing it to gain a competitive advantage against the latter species.[24] As a result of these characteristics, it is considered invasive in some states,[25] and has been banned for sale in New Hampshire[26] and Massachusetts.[27] The State of New York has classified it as an invasive plant species.[28] Despite these steps, the species is still available and widely used for urban plantings in many areas.

Fruit (samara): note the flat seed capsule and the angle of the "wings"

Fruit (samara): note the flat seed capsule and the angle of the "wings"- Typical yellow fall foliage

- Atypical orange-red fall colour

Purple leaves of cultivar 'Schwedleri'

Purple leaves of cultivar 'Schwedleri' Acer platanoides twig and buds.

Acer platanoides twig and buds.

Natural enemies

The larvae of a number of species of Lepidoptera feed on Norway maple foliage. Ectoedemia sericopeza, the Norway maple seedminer, is a moth of the family Nepticulidae. The larvae emerge from eggs laid on the samara and tunnel to the seeds. Norway maple is generally free of serious diseases, though can be attacked by the powdery mildew Uncinula bicornis, and verticillium wilt disease caused by Verticillium spp.[29] "Tar spots" caused by Rhytisma acerinum infection are common but largely harmless.[30] Aceria pseudoplatani is an acarine mite that causes a 'felt gall', found on the underside of leaves of both sycamores (Acer pseudoplatanus) and Norway maples.[31]

References

- "Acer platanoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019. 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "BSBI List 2007". Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- Flora Europaea: Acer platanoides distribution

- Den virtuella floran: Acer platanoides distribution

- Love, R (2003). "Introduced Species Summary Project: Norway maple (Acer platanoides)". Columbia University. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Introduced Species Summary Project: Norway Maple (Acer platanoides)". Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- "Acer platanoides". Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- "Acer platanoides". Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- "Norway Maple (Acer platanoides)". www.devostree.ca. Feb 12, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- Rushforth, K (1999). Trees of Britain and Europe. Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-220013-4.

- Mitchell, AF (1974). A Field Guide to the Trees of Britain and Northern Europe. Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-212035-7.

- Stace, C.A. (2010). New flora of the British Isles (Third ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-70772-5.

- Vedel, H.; Lange, J. (1960). Trees and bushes in wood and hedgerow. London, U.K.: Metheun & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-416-61780-1.

- "Differences Between Hard Maple and Soft Maple, The Wood Database".

- "Trees Near Their Limits – Alaska".

- History and Range of Norway Maple

- D'Cruz, Mark. "Ma-Ke Bonsai Care Guide for Acer platanoides". Ma-Ke Bonsai. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- "North American Maple Syrup Producers Manual". The Ohio State University College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Huxley, A. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-47494-5.

- "RHS Plant Selector – Acer platanoides 'Crimson King'". Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "Acer platanoides Princeton Gold='Prigo' (PBR)". Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Shannon L. Galbraith-Kent; Steven N. Handel (2008). "Invasive Acer platanoides inhibits native sapling growth in forest understorey communities". Journal of Ecology. 96 (2): 293–302. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01337.x.

- "Controlling Invasive Plants" (PDF).

- C. L. Cincotta; J. M. Adams; C. Holzapfel (2009). "Testing the enemy release hypothesis: a comparison of foliar insect herbivory of the exotic Norway maple (Acer platanoides L.) and the native sugar maple (A. saccharum L.)" (PDF). Biological Invasions. 11 (2): 379–388. doi:10.1007/s10530-008-9255-9.

- Swearingen, J.; Reshetiloff, K.; Slattery, B.; Zwicker, S. (2002). "Norway Maple". Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas. National Park Service and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

- "Invasive Species". New Hampshire Dept. of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- "Massachusetts Prohibited Plant List". Mass.gov. 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Interim List of Invasive Plant Species in New York State". Advisory Invasive Plant List. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- Phillips, D. H., & Burdekin, D. A. (1992). Diseases of Forest and Ornamental Trees. Macmillan ISBN 0-333-49493-8.

- Hudler, George (1998). Magical Mushrooms, Mischievous Molds. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 248.

- Plant Galls Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2013-07-10

External links

- Acer platanoides - information, genetic conservation units and related resources. European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN)

- Portrait of the Earth: Acer platanoides (Norway maple) — with winter images.