Agathyrsi

Agathyrsi (Greek: Ἀγάθυρσοι) were a people of Scythian,[1] or mixed Dacian-Scythian origin, who in the time of Herodotus occupied the plain of the Maris (Mures), in the mountainous part of ancient Dacia now known as Transylvania in present-day Romania. Their ruling class seems to have been of Scythian origin.[2]

Archaeology

The Scythian arrival to the Carpathian area is dated to 700 BC.[3] The Agathyrsi existence is archaeologically attested by the Ciumbrud inhumation type, in the upper Mureş area of the Transylvanian plateau. In contrast with the surrounding peoples who practiced incineration, the Ciumbrud people buried their dead. These tombs, containing Scythian artistic and armament metallurgy (e.g. acinaces), have moreover been dated to 550-450 BC — roughly the timeframe of Herodotus' writing. Archaeologists use the term "Thraco-Agathyrsian" to designate these characteristics, owing to the evident Thracian (or, more strictly speaking, Dacian) elements. At the time of Herodotus they were already absorbed by the native Dacians.[3][4]

History

Antiquity

Fifth century BC

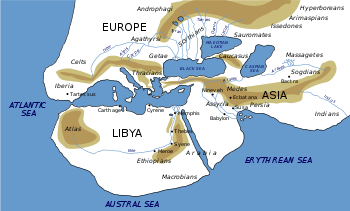

Herodotus, writing after 450 BC, localizes the Agathyrsi (Ἀγάθυρσοι) to Transylvania and the outer parts of Scythia, to the proximity of the Neuri.

- "From the country of the Agathyrsoi comes down another river, the Maris [Mureș], which empties itself into the same; and from the heights of Haemus descend with a northern course three mighty streams, the Atlas, the Auras, and the Tibisis, and pour their waters into it."[5]

- "After the Tauric land immediately come Scythians again, occupying the parts above the Tauroi and the coasts of the Eastern sea, that is to say the parts to the West of the Kimmerian Bosphorus and of the Maiotian lake, as far as the river Tanaïs [Don], which runs into the corner of this lake. In the upper parts which tend inland Scythia is bounded (as we know) by the Agathyrsoi first, beginning from the Ister [Danube], and then by the Neuroi, afterwards by the Androphagoi, and lastly by the Melanchlainoi."[6]

Later passages of Herodotus' text, related to Darius' campaign against the Scythians, again indicate that Agathyrsi dwelled next to the Neuri, i.e. even east of the Carpathians, somewhere in the western part of today's Ukraine.[7]

Herodotus himself distinguishes the Agathyrsi from the Scythians, but he implies that they are mutually closely related.[8] He recorded a Pontic Greek myth that the Agathyrsi were named after a legendary ancestor Agathyrsus, the oldest son of Heracles and the monster Echidna.[9]

- "Upon this he [Heracles] drew one of his bows (for up to that time Heracles, they say, was wont to carry two) and showed her the girdle, and then he delivered to her both the bow and the girdle, which had at the end of its clasp a golden cup; and having given them he departed. She then, when her sons had been born and had grown to be men, gave them names first, calling one of them Agathyrsos and the next Gelonos and the youngest Skythes; then bearing in mind the charge given to her, she did that which was enjoined. And two of her sons, Agathyrsos and Gelonos, not having proved themselves able to attain to the task set before them, departed from the land, being cast out by her who bore them; but Skythes the youngest of them performed the task and remained in the land: and from Skythes the son of Heracles were descended, they say, the succeeding kings of the Scythians (Skythians): and they say moreover that it is by reason of the cup that the Scythians still even to this day wear cups attached to their girdles: and this alone his mother contrived for Skythes. Such is the story told by the Hellenes who dwell about the Pontus."[10]

Herodotus also mentions that in other respects their customs approach nearly to those of the Thracians.[11] This is to say that Agathyrsi Scythians were completely denationalized at that time.[3]

- "The Agathyrsoi are the most luxurious of men and wear gold ornaments for the most part: also they have promiscuous intercourse with their women, in order that they may be brethren to one another and being all nearly related may not feel envy or malice one against another. In their other customs they have come to resemble the Thracians."[12]

The description of the pomp and splendor of the Agathyrsi of Transylvania is most strikingly confirmed by the discoveries made at Tufalau (Romania) – though this pomp is itself really pre-Scythian (Bronze Age local nobility) in character.[13]

Agathyrsi also appear in Herodotus' description of the expedition (516–513 BC) of Darius I of Persia (522–486 BC) against the Scythians in the N. Pontic.[14]

- The Scythians meanwhile having considered with themselves that they were not able to repel the army of Dareios alone by a pitched battle, proceeded to send messengers to those who dwelt near them: and already the kings of these nations had come together and were taking counsel with one another, since so great an army was marching towards them. Now those who had come together were the kings of the Tauroi, Agathyrsoi, Neuroi, Androphagoi, Melanchlainoi, Gelonians, Budinoi and Sauromatai.[15]

Agathyrsi, Neuri, Androphagi, Melanchlaini and Tauri refused to participate in the war against Persians, claiming that "the Persians have come not against us, but against those who were the authors of the wrong".[16]

In the second part of his campaign, Darius turned westwards and pursued two Scythian divisions at speed at a day’s distance, first through Scythian lands, then into the lands of those people who had refused alliance – Melanchlaini, Androphagi, Neuri - and finally to the border of the Agathyrsi, who stood firm and caused the Scythian divisions to return to Scythia, with Darius in pursuit.[17]

- "Scythians according to the plan which they had made continued to retire before him towards the land of those who had refused to give their alliance, and first towards that of the Melanchlainoi; and when Scythians and Persians both together had invaded and disturbed these, the Scythians led the way to the country of the Androphagoi; and when these had also been disturbed, they proceeded to the land of the Neuroi; and while these too were being disturbed, the Scythians went on retiring before the enemy to the Agathyrsoi. The Agathyrsoi however, seeing that their next neighbours also were flying from the Scythians and had been disturbed, sent a herald before the Scythians invaded their land and proclaimed to the Scythians not to set foot upon their confines, warning them that if they should attempt to invade the country, they would first have to fight with them. The Agathyrsoi then having given this warning came out in arms to their borders, meaning to drive off those who were coming upon them; but the Melanchlainoi and Androphagoi and Neuroi, when the Persians and Scythians together invaded them, did not betake themselves to brave defence but forgot their former threat and fled in confusion ever further towards the North to the desert region. The Scythians however, when the Agathyrsoi had warned them off, did not attempt any more to come to these, but led the Persians from the country of the Neuroi back to their own land."[7]

Herodotus further records the name of Spargapeithes (an Iranian name), a king of the Agathyrsi who killed the Scythian king Ariapeithes, in consequence, no doubt, of some border squabble or political rivalry in the lands lying between the Carpathians and the Tyras.[18]

- "Ariapithes, the Scythian king, had several sons, among them this Scylas, who was the child, not of a native Scyth, but of a woman of Istria. Bred up by her, Scylas gained an acquaintance with the Greek language and letters. Some time afterwards, Ariapithes was treacherously slain by Spargapithes, king of the Agathyrsoi; whereupon Scylas succeeded to the throne, and married one of his father's wives, a woman named Opoea."[19]

Fourth century BC

Aristotle mentions their practice of solemnly reciting their laws in a kind of sing-song to prevent their being forgotten, a practice in existence in his days,[8][20] also found at Gallic Druids. They tattooed their bodies, degrees of rank being indicated by the manner in which this was done, and colored their hair dark blue. Aristotle was the last author to mention them as a real people. O. Maenchen-Helfen in his World of the Huns (2004) maintains that since then they had led a purely literary existence.[21]

Roman period

First and second century AD

The Roman geographer Pomponius Mela (2,i) and the historian Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century AD, also list the Agathyrsi among the steppe tribes. Pliny alludes to their "blue hair."[22]

"Leaving Taphrae [a town near Crimea], and going along the mainland, we find in the interior the Auchetae, in whose country the Hypanis [the Bug river] has its rise, as also the Neuroe, in whose district the Borysthenes [the Dnieper river] has its source, the Geloni, the Thyssagetae, the Budini, the Basilidae, and the Agathyrsi with their azure-coloured hair. Above them are the Nomades, and then a nation of Anthropophagi or cannibals. On leaving Lake Buges [a gulf at the end of the Sea of Azov], above the Lake Mæotis we come to the Sauromatæ and the Essedones".[23]

This reference indicates that during the 1st century AD, the Agathyrsi lived somewhere in the western part of today's Ukraine. The 2nd century geographer Claudius Ptolemy lists the Agathyrsi among the tribes in 'European Sarmatia', between the Vistula and the Black Sea.[24]

Fourth century AD

In the 380s AD, the Agathyrsi are still mentioned by Ammianus Marcellinus in his Res Gestae Ch. 22.

- "Near to this is the sea of Azov, of great extent, from the abundant sources of which a great body of water pours through the straits of Patares, near the Black Sea; on the right are the islands Phanagorus and Hermonassa, which have been settled by the industry of the Greeks. Round the furthest extremity of this gulf dwell many tribes differing from one another in language and habits; the Jaxamatae, the Maeotae, the Jazyges, the Roxolani, the Alani, the Melanchlaenae, the Geloni, and the Agathyrsi, whose land abounds in adamant."[25]

- "The Danube, which is greatly increased by other rivers falling into it, passes through the territory of the Sauromatae, which extends as far as the river Don, the boundary between Asia and Europe. On the other side of this river the Alani inhabit the enormous deserts of Scythia, deriving their own name from the mountains around; and they, like the Persians, having gradually subdued all the bordering nations by repeated victories, have united them to themselves, and comprehended them under their own name. Of these other tribes the Neuri inhabit the inland districts, being near the highest mountain chains, which are both precipitous and covered with the everlasting frost of the north. Next to them are the Budini and the Geloni, a race of exceeding ferocity, who flay the enemies they have slain in battle, and make of their skins clothes for themselves and trappings for their horses. Next to the Geloni are the Agathyrsi, who dye both their bodies and their hair of a blue colour, the lower classes using spots few in number and small—the nobles broad spots, close and thick, and of a deeper hue."[26]

Servius on Aeneid 4.v.146 (late 4th century) also relates that the Agathyrsi of Scythia were known for coloring their hair blue. The slightly later, expanded text known as "Servius Danielis" further distinguished them from the Picts of Scotland who he said colored their skin blue; but some later mediaeval traditions recounted by Bede and Holinshed dubiously purported to connect the Agathyrsi of Scythia directly with the Picts of Scotland.[27]

Legacy

The gloss preserved by Stephen of Byzantium explains that the Greeks called the Trausi the Agathyrsi and we know that the Trausi lived in the Rhodope Mountains.[28]

In the 19th century, Niebuhr regards the Agathyrsi of Herodotus, or at least the people who occupied the position assigned to them by Herodotus, as the same people as the Getae or Dacians (North Thracians).[8]

Acatziri

An old theory of 19th century writers (Latham, V. St. Martin, Rambaud, Newman) which, according to the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, is based on 'less convincing proof', suggested an identification of the Agathyrsi with the later Agatziri or Akatziroi first mentioned by Priscus in Vol XI, 823, Byzantine History, who described them leading a nomadic life on the Lower Volga, and reported them as having been Hunnic subjects before the time of Attila. This older theory is not mentioned at all by modern scholars Helfen or Golden. According to E.A. Thompson, the conjecture that connects the Agathyrsi with Akatziri should be rejected outright.[29]

The Acatziri were a main force of the Attila's army in 448. Attila appointed Karadach or Curidachus as the Akatzirs' chieftain. (Thompson, p. 107).

Jordanes, who quotes Priscus in Getica, located the Acatziri to the south of the Aesti (Balts) — roughly the same region as the Agathyrsi of Transylvania — and he described them as "a very brave tribe ignorant of agriculture, who subsist on their flocks and by hunting."[30]

The Encyclopædia Britannica 1897 and 1911 editions consider the Acatziri to be precursors of the Khazars of later antiquity,[31] although modern scholars like Professor Peter Golden, E.A. Thompson and Maenchen-Helfen consider this theory to be nothing more than conjecture[32] and Thompson has rejected it outright.[29] There does not seem to be any modern reputable scholar that holds such a theory as factual though no reasons have been given.

See also

Notes

- The Thracians 700 BC-AD 46 The Thracians 700 BC-AD 46 by Christopher Webber and Angus Mcbride, 2001, ISBN 1-84176-329-2, page 16: "... back, which could be to accommodate a top-knot. Among the Agathyrsi (a Skythian tribe living near the Thracians, and practising some Thracian customs) the nobles also dyed their ..."

- Fisher, Gershevitch, Shater (1993) 184

- Parvan (1928) 48

- Thomson (1948) 399

- Herodotus IV, 49

- Herodotus IV,100

- Herodotus IV,125

- Smith (1878) 73

- Herodotus 4.8–10

- Herodotus IV,10

- Herodotus, Rawlinson G, Rawlinson H, Gardner (1859) 93

- Herodotus IV,104

- Parvan (1928) 69

- (See Herodotus 4.10, 4.48, 4.49, 4.78, 4.100, 4.102, 4.104, 4.119, 4.125).

- Herodotus IV,102

- Herodotus IV, 119

- Fol, Hammond (1988) 241

- Parvan (1928) 75

- Herodotus, IV

- Hrushevsky (1997) 101

- Maenchen-Helfen (2004) 451

- The Fourth Booke of Plinies Naturall History

- Pliny the Elder IV,26

- LacusCurtius • Ptolemy's Geography — Book III, Chapter 5.

- Ammianus Marcellinus XXII,8

- Amminanus Marcellinus XXXI,2

- Miles, D (2011), Heroic Saga and Classical Epic in Medieval Ireland, Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer

- Hrushevsky (1997) 97

- E.A. Thompson, The Huns (Peoples of Europe) Blackwell Publishing, Incorporated (March 1, 1999), pg 105

- The Origin And Deeds Of The Goths

- "Khazars" in Encyclopædia Britannica, 1897.

- An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz), 1992, p. 87

References

- Fol, A and Hammond NGL (1988): The expedition of Darius 513 BC, The Cambridge Ancient History John Boardman, N. G. L. Hammond (Editor), D. M. Lewis (Editor), M. Ostwald Cambridge University Press; 2 edition, ISBN 0521228042, ISBN 978-0521228046

- Latham, Robert Gordon (1854). "On the Name and Nation of the Dacian King Decebalus, with Notices of the Agathyrsi and Alani". Transactions of the Philological Society (6).

- Thomson, James Oliver (1948) History of Ancient Geography, publisher: Biblo-Moser, ISBN 0819601438, ISBN 978-0819601438

- Herodotus, Rawlinson George, Rawlinson Henry Creswicke, Wilkinson, Sir John Gardner, The History of Herodotus a new English version, Volume 3, London

- Hrushevsky, Mykhailo (1997) History of Ukraine-Rus': From prehistory to the eleventh century, publisher The Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, Edmonton, ISBN 9781894865104, ISBN 9781894865173

- Maclagan, Robert Craig (2003) Scottish Myths publisher, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 0766145239, ISBN 9780766145238

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (2004) World Of the Huns Publisher: University of California Press; ISBN 0520015967, ISBN 978-0520015968

- Parvan Vasile (1928) Dacia, Cambridge University Press

- Sulimirsky T and Taylor T (1992) The Scythians in The Cambridge Ancient History John Boardman I. E. S. Edwards E. Sollberger N. G. L. Hammond, Cambridge University Press; 2 edition, ISBN 0521227178, ISBN 978-0521227179

- William Bayne Fisher, Ilya Gershevitch, Ehsan Yar Shater (1993) The Median and Achaemenian PeriodsThe Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2, ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2

- Sir Smith, William (1878) A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography:Abacaenum-Hytanis London