Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway

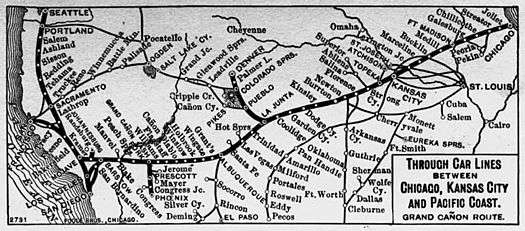

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (reporting mark ATSF), often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the larger railroads in the United States, named after the cities and towns of Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe. Chartered in February 1859, the railroad reached the Kansas–Colorado border in 1873 and Pueblo, Colorado, in 1876. To create a demand for its services, the railroad set up real estate offices and sold farmland from the land grants that it was awarded by Congress. Despite the namesake, its mainline did not directly serve Santa Fe, due to the mountainous terrain, the metropolitan city of Albuquerque instead served New Mexico and the Santa Fe area.

| |

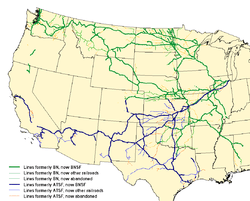

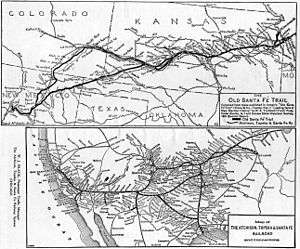

Santa Fe system (shown in blue) at the time of the BNSF merger | |

.jpg) ATSF 5051, an EMD SD40-2, leads a train through Marceline, Missouri in August 1983. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Chicago, Illinois Kansas City, Missouri Los Angeles, California |

| Reporting mark | ATSF |

| Locale | |

| Dates of operation | 1859–1996 |

| Successor | BNSF Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 13,115 miles (21,107 km) |

The Santa Fe was a pioneer in intermodal freight transport, an enterprise that (at one time or another) included a tugboat fleet and an airline, the short-lived Santa Fe Skyway.[1] Its bus line extended passenger transportation to areas not accessible by rail, and ferryboats on the San Francisco Bay allowed travelers to complete their westward journeys to the Pacific Ocean. The AT&SF was the subject of a popular song, Harry Warren and Johnny Mercer's "On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe", written for the film, The Harvey Girls (1946).

The railroad officially ceased operations on December 31, 1996, when it merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad to form the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway.

History

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway

The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) was chartered on February 11, 1859, to join Atchison and Topeka, Kansas, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. In its early years, the railroad opened Kansas to settlement. Much of its revenue came from wheat grown there and from cattle driven north from Texas to Wichita and Dodge City by September 1872.[2]

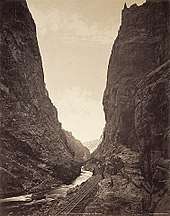

Rather than turn its survey southward at Dodge City, AT&SF headed southwest over Raton Pass because of coal deposits near Trinidad, Colorado and Raton, New Mexico. The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad (D&RG) was also aiming at Raton Pass, but AT&SF crews arose early one morning in 1878 and were hard at work with picks and shovels when the D&RG crews showed up for breakfast. At the same time the two railroads had a series of skirmishes over occupancy of the Royal Gorge west of Cañon City, Colorado; physical confrontations led to two years of armed conflict that became known as the Royal Gorge Railroad War. Federal intervention prompted an out-of-court settlement on February 2, 1880, in the form of the so-called "Treaty of Boston", wherein the D&RG was allowed to complete its line and lease it for use by the Santa Fe. D&RG paid an estimated $1.4 million to Santa Fe for its work within the Gorge and agreed not to extend its line to Santa Fe, while the Santa Fe agreed to forego its planned routes to Denver and Leadville.[2]

Building across Kansas and eastern Colorado was simple, with few natural obstacles (certainly fewer than the railroad was to encounter further west), but the railroad found it almost economically impossible because of the sparse population. It set up real estate offices in the area and promoted settlement across Kansas on the land that was granted to it by Congress in 1863. It offered discounted fares to anyone who traveled west to inspect land; if the land was purchased, the railroad applied the passenger's fare toward the price of the land.

AT&SF reached Albuquerque in 1880; Santa Fe, the original destination of the railroad, found itself on a short branch from Lamy, New Mexico.[3] In March 1881 AT&SF connected with the Southern Pacific (SP) at Deming, New Mexico, forming the second transcontinental rail route. The railroad then built southwest from Benson, Arizona, to Nogales on the Mexican border where it connected with the Sonora Railway, which the AT&SF had built north from the Mexican port of Guaymas.[2]

Atlantic and Pacific Railway

The Atlantic & Pacific Railroad (A&P) was chartered in 1866 to build west from Springfield, Missouri, along the 35th parallel of latitude (approximately through Amarillo, Texas, and Albuquerque, New Mexico) to a junction with the SP at the Colorado River. The infant A&P had no rail connections. The line that was to become the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (the Frisco) would not reach Springfield for another four years, and SP did not build east from Mojave to the Colorado River until 1883. The A&P started construction in 1868, built southwest into what would become Oklahoma, and promptly entered receivership.[2]

In 1879, the A&P struck a deal with the Santa Fe and the Frisco. Those railroads would jointly build and own the A&P railroad west of Albuquerque. In 1883 A&P reached Needles, California, where it connected with the SP, but the Tulsa-Albuquerque portion of the A&P was still unbuilt.[2]

Expansion

The Santa Fe began to expand: a line from Barstow, California, to San Diego in 1885 and to Los Angeles in 1887; control of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway (Galveston-Fort Worth-Purcell) in 1886 and a line between Wichita and Fort Worth in 1887; lines from Kansas City to Chicago, from Kiowa, Kansas to Amarillo, and from Pueblo to Denver (paralleling the D&RGW) in 1888; and purchase of the Frisco and the Colorado Midland Railway in 1890.[2] By January 1890, the entire system consisted of some 7,500 miles of track.[4]

The Panic of 1893 had the same effect on the AT&SF that it had on many other railroads; financial problems and subsequent reorganization. In 1895 AT&SF sold the Frisco and the Colorado Midland and wrote off the losses, but it still retained control of the A&P.[2]

The Santa Fe Railway still wanted to reach California on its own rails (it leased the SP line from Needles to Barstow), and the state of California eagerly courted the railroad to break SP's monopoly. In 1897 the railroad traded the Sonora Railway of Mexico to SP for their line between Needles and Barstow, giving AT&SF its own line from Chicago to the Pacific coast. It was unique in that regard until the Milwaukee Road completed its extension to Puget Sound in 1909.[2] AT&SF purchased the Southern California Railway on Jan. 17, 1906; with this purchase they also acquired the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Valley Railroad and the California Central Railway.

Subsequent expansion of the Santa Fe Railway encompassed lines from Amarillo to Pecos (1899); from Ash Fork, Arizona to Phoenix (1901); from Williams, Arizona to the Grand Canyon (1901); the Belen Cutoff from the Pecos line at Texico to Dalies (northwest of Belen), bypassing the grades of Raton Pass (1907); and the Coleman Cutoff, from Texico to Coleman, Texas, near Brownwood (1912).[2]

In 1907, AT&SF and SP jointly formed the Northwestern Pacific Railroad (NWP), which took over several short railroads and built new lines connecting them to form a route from San Francisco north to Eureka, California. In 1928, Santa Fe sold its half of the NWP to SP. Also in 1928, Santa Fe purchased the U.S. portion of the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Railway (the Mexican portion of the line became the Chihuahua-Pacific Railway, now part of National Railways of Mexico).

Because long stretches of its main line traverse areas without water, Santa Fe was one of the first buyers of diesel locomotives for freight service. The railroad was known for its passenger trains, notably the Chicago-Los Angeles El Capitan and Super Chief (currently operated as Amtrak's Southwest Chief), and for the on-line eating houses and dining cars that were operated by Fred Harvey.[2] Several of these Harvey Houses survive - most notably the El Tovar, which is positioned right alongside the Grand Canyon, and La Posada Hotel in Winslow, Ariz.

On March 29, 1955, the railway was one of many companies that sponsored attractions in Disneyland with its 5-year sponsorship of all Disneyland trains and stations until 1974.[5]

Post-World War II construction projects included an entrance to Dallas from the north, and relocation of the main line across northern Arizona, between Seligman and Williams.[2] In 1960, AT&SF bought the Toledo, Peoria & Western Railroad (TP&W), then sold a half interest to the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR). The TP&W cut straight east across Illinois from near Fort Madison, Iowa (Lomax, IL), to a connection with the PRR at Effner, Indiana (Illinois-Indiana border), forming a bypass around Chicago for traffic moving between the two lines. The TP&W route did not mesh with the traffic patterns Conrail developed after 1976, so AT&SF bought back the other half, merged the TP&W in 1983, then sold it back into independence in 1989.[2]

Attempted Southern Pacific merger

AT&SF began to talk mergers in the 1980s. The Southern Pacific Santa Fe Railroad (SPSF) was a proposed merger between the parent companies of the Southern Pacific and AT&SF announced on December 23, 1983. As part of the joining of the two firms, all rail and non-rail assets owned by Santa Fe Industries and the Southern Pacific Transportation Company were placed under the control of a holding company, the Santa Fe–Southern Pacific Corporation. The merger was subsequently denied by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) on the basis that it would create too many duplicate routes.[6][7]

The companies were so confident the merger would be approved that they began repainting locomotives and non-revenue rolling stock in a new unified paint scheme. While Southern Pacific (railroad) was sold off to Rio Grande Industries, all of the SP's real estate holdings were consolidated into a new company, Catellus Development Corporation, making it California state's largest private landowner, of which Santa Fe remained the owner (effectively “stealing” the land from SP shareholders). (In the early 1980s gold was discovered on several properties west of Battle Mountain Nevada along I-80, on ground owned by the Santa Fe Railroad (formerly SP). The property company created Santa Fe Pacific Corporation (a name correlation of Santa Fe and Southern Pacific) to develop the properties. It was sold to Newmont during 1997 in preparation of the merger with Burlington Northern). Sometime later, Catellus would purchase the Union Pacific Railroad's interest in the Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal (LAUPT).[2] After the sale of Southern Pacific to Rio Grande Industries, the SPSF name reverted to Santa Fe Industries, the holding company of AT&SF.

Burlington Northern merger

On September 22, 1995, AT&SF merged with Burlington Northern Railroad to form the Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway (BNSF). Some of the challenges resulting from the joining of the two companies included the establishment of a common dispatching system, the unionization of AT&SF's non-union dispatchers, and incorporating AT&SF's train identification codes throughout. The two lines maintained separate operations until December 31, 1996 when it officially became BNSF.

| 1870 | 1945 | |

| Gross operating revenue | $182,580 | $528,080,530 |

|---|---|---|

| Total track length | 62 miles (100 km) | 13,115 miles (21,107 km) |

| Freight carried | 98,920 tons | 59,565,100 tons |

| Passengers carried | 33,630 | 11,264,000 |

| Locomotives owned | 6 | 1,759 |

| Unpowered rolling stock owned | 141 | 81,974 freight cars 1,436 passenger cars |

- Source: Santa Fe Railroad (1945), Along Your Way, Rand McNally, Chicago, Illinois.

| ATSF/GC&SF/P&SF | Oklahoma City-Ada-Atoka | FtWorth & Rio Grande | KCM&O/KCM&O of Texas | Clinton & Oklahoma Western | New Mexico Central | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 13862 | 14 | 42 | 330 | 2 | 1 |

| 1933 | 8712 | 12 | 18 | (incl P&SF) | (incl P&SF) | (incl ATSF) |

| 1944 | 37603 | 45 | (incl GC&SF) | |||

| 1960 | 36635 | 20 | ||||

| 1970 | 48328 | (merged) |

| ATSF/GC&SF/P&SF | Oklahoma City-Ada-Atoka | FtWorth & Rio Grande | KCM&O/KCM&O of Texas | Clinton & Oklahoma Western | New Mexico Central | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 1410 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 1933 | 555 | 0.1 | 0.8 | (incl P&SF) | (incl P&SF) | (incl ATSF) |

| 1944 | 6250 | 0.2 | (incl GC&SF) | |||

| 1960 | 1689 | 0 | ||||

| 1970 | 727 | (merged) |

Company officers

- Cyrus K. Holliday: 1860–1863

- Samuel C. Pomeroy: 1863–1868

- William F. Nast: September 1868

- Henry C. Lord: 1868–1869

- Henry Keyes: 1869–1870

- Ginery Twichell: 1870–1873

- Henry Strong: 1873–1874

- Thomas Nickerson: 1874–1880

- T. Jefferson Coolidge: 1880–1881

- William Barstow Strong: 1881–1889

- Allen Manvel:[4] 1889–1893

- Joseph Reinhart: 1893–1894

- Aldace F. Walker: 1894–1895[8]

- Edward Payson Ripley: 1896–1920

- William Benson Storey: 1920–1933

- Samuel T. Bledsoe: 1933–1939

- Edward J. Engel: 1939–1944

- Fred G. Gurley: 1944–1958

- Ernest S. Marsh: 1958–1967

- John Shedd Reed: 1967–1978[9]

- Lawrence Cena; 1978-1985

- W. John Swartz: 1985–1988

- Mike Haverty: 1989–1991

- Robert Krebs: 1991–1995

- Alfred W. Nickerson

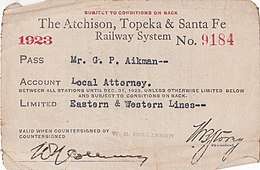

Passenger service

AT&SF was widely known for its passenger train service in the first half of the 20th century. AT&SF introduced many innovations in passenger rail travel, among these the "Pleasure Domes" of the Super Chief (billed as the "...only dome car[s] between Chicago and Los Angeles" when they were introduced in 1951) and the "Big Dome" Lounge cars and double-decker Hi-Level cars of the El Capitan, which entered revenue service in 1954. The railroad was among the first to add dining cars to its passenger trains, a move which began in 1891, following the examples of the Northern Pacific and Union Pacific railroads. The AT&SF offered food on board in a dining car or at one of the many Harvey House restaurants that were strategically located throughout the system.

In general, the same train name was used for both directions of a particular train. The exceptions to this rule included the Chicagoan and Kansas Cityan trains (both names referred to the same service, but the Chicagoan was the eastbound version, while the Kansas Cityan was the westbound version), and the Eastern Express and West Texas Express. All AT&SF trains that terminated in Chicago did so at Dearborn Station. Trains terminating in Los Angeles arrived at AT&SF's La Grande Station until May 1939, when Los Angeles Union Station was opened.

The railway's extensive network was also home to a number of regional services. These generally couldn't boast of the size or panache of the transcontinental trains, but built up enviable reputations of their own nonetheless. Of these, the Chicago-Texas trains were the most famous and impressive. The San Diegans, which ran from Los Angeles to San Diego, were the most popular and durable, becoming to the Santa Fe what New York City-Philadelphia trains were to the Pennsylvania Railroad. But Santa Fe flyers also served Tulsa, Oklahoma, El Paso, Texas, Phoenix, Arizona (the Hassayampa Flyer), and Denver, Colorado, among other cities not on their main line.

To reach smaller communities, the railroad operated mixed (passenger and freight) trains or gas-electric doodlebug rail cars. The latter were later converted to diesel power, and one pair of Budd Rail Diesel Cars were eventually added. After World War II, Santa Fe Trailways buses replaced most of these lesser trains. These smaller trains generally were not named; only the train numbers were used to differentiate services.

The ubiquitous passenger service inspired the title of the 1946 Academy-Award-winning Harry Warren tune "On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe." The song was written in 1945 for the film The Harvey Girls, a story about the waitresses of the Fred Harvey Company's restaurants. It was sung in the film by Judy Garland and recorded by many other singers, including Bing Crosby. In the 1970s, the railroad used Crosby's version in a commercial.

AT&SF ceased operating passenger trains on May 1, 1971, when it conveyed its remaining trains to Amtrak. These included the Super Chief/El Capitan, the Texas Chief and the San Diegan (though Amtrak reduced the San Diegan from three round trips to two). Discontinued were the San Francisco Chief, the ex-Grand Canyon, the Tulsan, and a Denver–La Junta local.[10] ATSF had been more than willing to retain the San Diegan and its famed Chiefs. However, any railroad that opted out of Amtrak would have been required to operate all of its passenger routes until at least 1976. The prospect of having to keep operating its less successful routes, especially the money-bleeding 23/24 (the former Grand Canyon) led ATSF to get out of passenger service altogether.[11]

Amtrak still runs the Super Chief and San Diegan today as the Southwest Chief and Pacific Surfliner, respectively, although the original routes and equipment have been modified by Amtrak.

Named trains

AT&SF operated the following named trains on regular schedules:

- The Angel: San Francisco, California — Los Angeles, California — San Diego, California (this was the southbound version of the Saint)

- The Angelo: San Angelo, Texas — Fort Worth, Texas (on the GC&SF)

- The Antelope: Oklahoma City, Oklahoma — Kansas City, Missouri

- Atlantic Express: Los Angeles, California — Kansas City, Missouri (this was the eastbound version of the Los Angeles Express).

- California Express: Chicago, Illinois — Kansas City, Missouri — Los Angeles, California

- California Fast Mail: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California — San Francisco, California

- California Limited: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California

- California Special: Clovis, New Mexico — Houston, Texas (with through connections to California via the San Francisco Chief at Clovis)

- Cavern: Clovis, New Mexico — Carlsbad, New Mexico (connected with the Scout).

- Centennial State: Denver, Colorado — Chicago, Illinois

- Central Texas Express: Sweetwater, Texas — Lubbock, Texas

- Chicagoan: Kansas City, Missouri — Chicago, Illinois (this was the eastbound version of the Kansas Cityan passenger train).

- Chicago Express: Newton, Kansas — Chicago, Illinois

- Chicago Fast Mail: San Francisco, California — Los Angeles, California — Chicago, Illinois

- Chicago-Kansas City Flyer: Chicago, Illinois — Kansas City, Missouri

- The Chief: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California

- Eastern Express: Lubbock, Texas — Amarillo, Texas (this was the eastbound version of the West Texas Express).

- El Capitan: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California

- El Pasoan: El Paso, Texas — Albuquerque, New Mexico

- El Tovar: Los Angeles, California — Chicago, Illinois (via Belen)

- Fargo Fast Mail/Express: Belen, New Mexico — Amarillo, Texas — Kansas City, Missouri — Chicago, Illinois

- Fast Fifteen: Newton, Kansas — Galveston, Texas

- Fast Mail Express: San Francisco, California (via Los Angeles) — Chicago, Illinois

- Golden Gate: Oakland, California — Bakersfield, California with coordinated connecting bus service to Los Angeles and San Francisco

- Grand Canyon Limited: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California

- The Hopi: Los Angeles, California — Chicago, Illinois

- Kansas Cityan: Chicago, Illinois — Kansas City, Missouri (this was the westbound version of the Chicagoan passenger train).

- Kansas City Chief: Kansas City, Missouri — Chicago, Illinois

- Los Angeles Express: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California (this was the westbound version of the Atlantic Express).

- The Missionary: San Francisco, California — Belen, New Mexico — Amarillo, Texas — Kansas City, Missouri — Chicago, Illinois

- Navajo: Chicago, Illinois — San Francisco, California (via Los Angeles)

- Oil Flyer: Kansas City, Missouri — Tulsa, Oklahoma with through sleepers to Chicago via other trains

- Overland Limited: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California

- Phoenix Express: Los Angeles, California — Phoenix, Arizona

- The Ranger: Kansas City, Missouri — Chicago, Illinois

- The Saint: San Diego, California — Los Angeles, California — San Francisco, California (this was the northbound version of the "Angel")

- San Diegan: Los Angeles, California — San Diego, California

- San Francisco Chief: San Francisco, California — Chicago, Illinois

- San Francisco Express: Chicago, Illinois — San Francisco, California (via Los Angeles)

- Santa Fe de Luxe: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California — San Francisco, California

- Santa Fe Eight: Belen, New Mexico — Amarillo, Texas — Kansas City, Missouri — Chicago, Illinois

- The Scout: Chicago, Illinois — San Francisco, California (via Los Angeles)

- South Plains Express: Sweetwater, Texas — Lubbock, Texas

- Super Chief: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California

- The Texan: Houston, Texas — New Orleans, Louisiana (on the GC&SF between Galveston and Houston, then via the Missouri Pacific Railroad between Houston and New Orleans).

- Texas Chief: Galveston, Texas (on the GC&SF) — Chicago, Illinois

- Tourist Flyer: Chicago, Illinois — San Francisco, California (via Los Angeles)

- The Tulsan: Tulsa, Oklahoma — Kansas City, Mo. with through coaches to Chicago, Illinois via other trains (initially the Chicagoan/Kansas Cityan)

- Valley Flyer: Oakland, California — Bakersfield, California

- West Texas Express: Amarillo, Texas — Lubbock, Texas (this was the westbound version of the Eastern Express).

Special trains

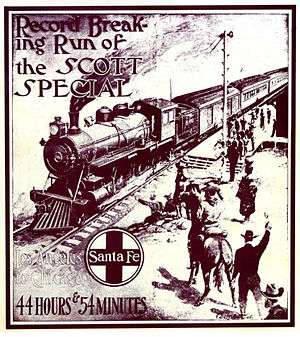

Occasionally, a special train was chartered to make a high-profile run over the Santa Fe's track. These specials were not included in the railroad's regular revenue service lineup, but were intended as one-time (and usually one-way) traversals of the railroad. Some of the more notable specials include:

- Cheney Special: Colton, California — Chicago, Illinois (a one-time train that ran in 1895 on behalf of B.P. Cheney, a director of the Santa Fe).

- Clark Special: Winslow, Arizona — Chicago, Illinois (a one-time train that ran in 1904 on behalf of Charles W. Clarke, the son of then-Arizona senator William Andrew Clarke).

- David B. Jones Special: Los Angeles, California — Chicago, Illinois and on to Lake Forest, Illinois (a one-time, record-breaking train that ran between May 5 to 8, 1923, on behalf of the president of the Mineral Point Zinc Company).

- Huntington Special: Argentine, Kansas — Chicago, Illinois (a one-time train that ran in 1899 on behalf of Collis P. Huntington).

- H.P. Lowe Special: Chicago, Illinois — Los Angeles, California (a one-time, record-breaking train that ran in 1903 on behalf of the president of the Engineering Company of America).

- Miss Nellie Bly Special: San Francisco, California — Chicago, Illinois (a one-time, record-breaking train that ran in 1890 on behalf of Nellie Bly, a reporter for the New York World newspaper).

- Peacock Special: Los Angeles, California — Chicago, Illinois (a one-time train that ran in 1900 on behalf of A.R. Peacock, vice-president of the Carnegie Steel and Iron Company).

- Scott Special: Los Angeles, California — Chicago, Illinois (the most well-known of Santa Fe's "specials," also known as the Coyote Special, the Death Valley Coyote, and the Death Valley Scotty Special: a one-time, record-breaking train that ran in 1905, essentially as a publicity stunt).

- Wakarusa Creek Picnic Special: Topeka, Kansas — Pauline, Kansas (a one-time train that took picnickers on a 30-minute trip, at a speed of 14 miles-per-hour, to celebrate the official opening of the line on April 26, 1869).

Signals

The Santa Fe employed several distinctive wayside and crossing signal styles. In an effort to reduce grade crossing accidents, the Santa Fe was an early user of wigwag signals from the Magnetic Signal Company beginning in the 1920s. They had several distinct styles that were not commonly seen elsewhere. Model 10's which had the wigwag motor and banner coming from halfway up the mast with the crossbucks on top were almost unique to the Santa Fe—the Southern Pacific also had a few as well. Upper quadrant Magnetic Flagmen were used extensively on the Santa Fe as well—virtually every small town main street and a number of city streets had their crossings protected by these unique wigwags. Virtually all the wigwags were replaced with modern signals by the turn of the 21st century.

The railroad was also known for its tall "T-2 style" upper quadrant semaphores which provided traffic control on its lines. Again, the vast majority of these have been replaced by the beginning of the 21st century with fewer than 50 still remaining in use in New Mexico as of 2015.

Paint schemes

Steam locomotives

The Santa Fe operated a large and varying fleet of steam locomotives. Among them was the 2-10-2 "Santa Fe", originally built for the railroad by Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1903.[12][13] The railroad would ultimately end up with the largest fleet of them, at over 300. Aside from the 2-10-2, Santa Fe rostered virtually every type of steam locomotive imaginable, including 4-4-2 Atlantics, 2-6-0 Moguls, 2-8-0 Consolidations, 2-8-2 Mikados, 2-10-0 Decapods, 2-6-2 Prairies, 4-8-4 Northerns, 4-6-4 Hudsons, 4-6-2 Pacifics, 4-8-2 Mountains, 2-8-4 Berkshires, and 2-10-4 Texas. The railroad also operated a fleet of heavy articulated steam locomotives including 1158 class 2-6-6-2s, 2-8-8-0s, 2-10-10-2s, 2-8-8-2s, and the rare 4-4-6-2 Mallet type. The Railroad retired its last steam locomotive in 1959.

During the twentieth century, all but one of these was painted black, with white unit numbers on the sand domes and three sides of the tender. Cab sides were lettered "AT&SF" when operated in most parts of Texas, and "AT&SF" otherwise, also in white. The subsidiary Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe often painted all or part of the smokebox (between the boiler and the headlight) white or silver. In 1940, the circle and cross emblem was applied to the tenders of a few passenger locomotives, but these were all later painted over. After World War II, "Santa Fe" appeared on tender sides of mainline road locomotives in white, above the unit number. Locomotives were delivered from Baldwin with white paint on the wheel rims, but the road did not repaint these "whitewalls" after shopping the locomotives. After World War II, side rods and valve gear were painted chrome yellow. For a short time, Pacific types 1369 and 1376 were semi-streamlined for "Valley Flyer" service, with a unique paint scheme in colors similar to those used on the new passenger diesels. More unique was the two-tone light blue over royal blue scheme of streamlined Hudson type 3460.

While most of the Santa Fe's steam locomotives were retired and sold for scrap, a handful were saved and a few ended up as notable locomotives. Among them is Santa Fe 3751, a 4-8-4 Northern type, built by Baldwin in 1927, was once on display at Viaduct Park near the AT&SF depot in San Bernardino, California. The locomotive was moved out of the park in 1986 to be restored and after almost 5 years of restoration, 3751 made its first run on a 4-day trip from Los Angeles to Bakersfield and return in December 1991. The trip marked the beginning of 3751's career in excursion service. The more-modern Santa Fe 2926, another 4-8-4 delivered by Baldwin in 1944 and based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, is being restored for operation by the New Mexico Steam Locomotive and Rail Historical Society of Albuquerque, which has expended 114,000 man-hours and $1,700,000 in donated funds on her restoration since 2002.[14]

Diesel locomotives

Passenger

Santa Fe's first set of diesel-electric passenger locomotives was placed in service on the Super Chief in 1936, and consisted of a pair of blunt-nosed units (EMC 1800 hp B-B) designated as Nos. 1 and 1A. The upper portion of the sides and ends of the units were painted gold, while the lower section was a dark olive green color; an olive stripe also ran along the sides and widened as it crossed the front of the locomotive.

Riveted to the sides of the units were metal plaques bearing a large "Indian Head" logo, which owed its origin to the 1926 Chief "drumhead" logo. "Super Chief" was emblazoned on a plaque located on the front. The rooftop was light slate gray, rimmed by a red pinstripe. This unique combination of colors was called the Golden Olive paint scheme.[15][16] Before entering service, Sterling McDonald's General Motors Styling Department augmented the look with the addition of red and blue striping along both the sides and ends of the units in order to enhance their appearance.

In a little over a year, the EMC E1 (a new and improved streamlined locomotive) would be pulling the Super Chief and other passenger consists, resplendent in the now-famous Warbonnet paint scheme devised by Leland Knickerbocker of the GM Art and Color Section. Its design is protected under a U.S. patent,[17] granted on November 9, 1937. It is reminiscent of a Native American ceremonial headdress. The scheme consisted of a red "bonnet" which wrapped around the front of the unit and was bordered by a yellow stripe and black pinstripe. The extent of the bonnet varied according to the locomotive model, and was largely determined by the shape and length of the carbody. The remainder of the unit was either painted silver or was composed of stainless-steel panels.

All units wore a nose emblem consisting of an elongated yellow "Circle and Cross" emblem with integral "tabs" on the nose and the sides, outlined and accented with black pinstripes, with variances according to the locomotive model. "SANTA FE" was displayed on the horizontal limb of the cross in black, Art Deco-style lettering. This emblem has come to be known as the "cigar band" due to its uncanny resemblance to the same. On all but the "Erie-built" units (which were essentially run as a demonstrator set), GE U28CG, GE U30CG, and FP45 units, a three-part yellow and black stripe ran up the nose behind the band.

A "Circle and Cross" motif (consisting of a yellow field, with red quadrants, outlined in black) was painted around the side windows on "as-delivered" E1 units. Similar designs were added to E3s, E6s, the DL109/110 locomotive set, and ATSF 1A after it was rebuilt and repainted. The sides of the units typically bore the words "SANTA FE" in black, 5"– or 9"–high extra extended Railroad Roman letters, as well as the "Indian Head" logo,[18][19] with a few notable exceptions.

Railway identity on diesel locomotives in passenger service:

| Locomotive Type | "Indian Head" | "Circle and Cross" | "Santa Fe" | Logotype | Starting Year | Comments |

| ATSF 1 | Yes | Yes* | Yes | No | 1937 | "Circle and Cross" added to No. 1 after rebuild in May 1938 |

| EMC E1, E3, & E6 | Yes* | Yes | Yes | No | 1937 | "Indian Head" added to B units at a later date |

| ALCO DL109/110 | Yes* | Yes | Yes | No | 1941 | No "Indian Head" on B unit |

| EMD FT | Yes* | No | Yes | No | 1945 | "Indian Head" added to B units at a later date |

| ALCO PA / PB | Yes* | No | Yes | No | 1946 | "Indian Head" added to B units at a later date |

| EMD F3 | Yes* | No | Yes | No | 1946 | "Indian Head" on B units only |

| FM Erie-built | Yes* | No | Yes* | No | 1947 | "Indian Head" and "SANTA FE" on A units only |

| EMD F7 | Yes* | No | Yes* | No | 1949 | "Indian Head" on B units only; "SANTA FE" added in 1954 |

| EMD E8 | Yes* | No | Yes | No | 1952 | "Indian Head" on B units only |

| GE U28CG | No | No | No | Yes | 1966 | "Santa Fe" logotype in large, red "billboard"-style letters |

| GE U30CG | No | No | Yes* | No | 1967 | 5"–high non-extended "SANTA FE" letters |

| EMD FP45 | No | No | Yes* | No | 1967 | 9"–high "SANTA FE" letters |

Source: Pelouze, Richard W. (1997). Trademarks of the Santa Fe Railway. The Santa Fe Railway Historical and Modeling Society, Inc., Highlands Ranch, Colorado pp. 47–50.

In later years, Santa Fe adapted the scheme to its gas-electric "doodlebug" units.[20] The standard for all of Santa Fe's passenger locomotives, the Warbonnet is considered by many to be the most recognized corporate logo in the railroad industry. Early after Amtrak's inception in 1971, Santa Fe embarked on a program to paint over the red bonnet on its F units that were still engaged in hauling passenger consists with yellow (also called Yellowbonnets) or dark blue (nicknamed Bluebonnets), as it no longer wanted to project the image of a passenger carrier.

Freight

Diesels used as switchers between 1935 and 1960 were painted black, with just a thin white or silver horizontal accent stripe (the sills were painted similarly). The letters "A.T.& S.F." were applied in a small font centered on the sides of the unit, as was the standard blue and white "Santa Fe" box logo. After World War II, diagonal white or silver stripes were added to the ends and cab sides to increase the visibility at grade crossings (typically referred to as the Zebra Stripe scheme). "A.T.& S.F." was now placed along the sides of the unit just above the accent stripe, with the blue and white "Santa Fe" box logo below.

Due to the lack of abundant water sources in the American desert, the Santa Fe Railway was among the first railroads to receive large numbers of streamlined diesel locomotives for use in freight service, in the form of the EMD FT. For the first group of FTs, delivered between December 1940 and March 1943 (#100–#119), the railroad selected a color scheme consisting of dark blue accented by a pale yellow stripe up the nose, and pale yellow highlights around the cab and along the mesh and framing of openings in the sides of the engine compartment; a thin, red stripe separated the blue areas from the yellow.

Because of a labor dispute with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, who insisted that every cab in a diesel-electric locomotive consist must be manned, FT sets #101-#105 were delivered in A-B-B-B sets, instead of the A-B-B-A sets used by the rest of Santa Fe's FT's. The Santa Fe quickly prevailed in this labor dispute, and FT sets from #106-onward were delivered as A-B-B-A sets.

The words SANTA FE were applied in yellow in a 5"–high extended font, and centered on the nose was the "Santa Fe" box logo (initially consisting of a blue cross, circle, and square painted on a solid bronze sheet, but subsequently changed to baked steel sheets painted bronze with the blue identifying elements applied on top). Three thin, pale yellow stripes (known as Cat Whiskers) extended from the nose logo around the cab sides. In January, 1951, Santa Fe revised the scheme to consist of three yellow stripes running up the nose, with the addition of a blue and yellow Cigar Band (similar in size and shape to that applied to passenger units); the blue background and elongated yellow "SANTA FE" lettering were retained.

The years 1960 to 1972 saw non-streamlined freight locomotives sporting the "Billboard" color scheme (sometimes referred to as the "Bookends" or "Pinstripe" scheme), wherein the units were predominantly dark blue with yellow ends and trim, with a single yellow accent pinstripe. The words "Santa Fe" were applied in yellow in large bold serif letters (logotype) to the sides of the locomotive below the accent stripe (save for yard switchers which displayed the "SANTA FE" in small yellow letters above the accent stripe, somewhat akin to the Zebra Stripe arrangement).

From 1972 to 1996, and even on into the BNSF era, the company adopted a new paint scheme often known among railfans as the "Yellowbonnet", which placed more yellow on the locomotives (reminiscent of the company's retired Warbonnet scheme); the goal again was to ensure higher visibility at grade crossings. The truck assemblies, previously colored black, now received silver paint.

In 1965, the road took delivery of ten GE U28CG dual-service roadswitcher locomotives equally suited to passenger or fast freight service. These wore a variation of the "Warbonnet" scheme in which the black and yellow separating stripes disappeared. The "Santa Fe" name was emblazoned on the sides in large black letters, using the same stencils used on freight engines; these were soon repainted in red. In 1989, Santa Fe resurrected this version of the "Warbonnet" scheme and applied it to two SDFP45 units, #5992 and #5998. The units were re-designated as #101 and #102 and reentered service on July 4, 1989 as part of the new "Super Fleet" campaign (the first Santa Fe units to be so decorated for freight service). The six remaining FP45 units were thereafter similarly repainted and renumbered. From that point forward, most new locomotives wore red and silver, and many retained this scheme after the Burlington Northern Santa Fe merger, some with "BNSF" displayed across their sides.

For the initial deliveries of factory-new "Super Fleet" equipment, Santa Fe took delivery of the EMD GP60M and General Electric B40-8W which made the Santa Fe the only US Class I railroad to operate new 4-axle (B-B) freight locomotives equipped with the North American Safety Cab intended for high-speed intermodal service.

Several experimental and commemorative paint schemes emerged during the Santa Fe's diesel era. One combination was developed and partially implemented in anticipation of a merger between the parent companies of the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific (SP) railroads in 1984. The red, yellow, and black paint scheme with large yellow block letters on the sides and ends of the units of the proposed Southern Pacific Santa Fe Railroad (SPSF) has come to be somewhat derisively known among railfans as the Kodachrome livery, due to the similarity in colors to the boxes containing slide film sold by the Eastman Kodak Company under the same name. Santa Fe units repainted in this scheme were labeled "SF", Southern Pacific units "SP", and some (presumably new) units wore the letters " SPSF". After the ICC's denial of the merger, railfans joked that SPSF really stood for "Shouldn't Paint So Fast."[21]

Warbonnet roof details

Warbonnet roof details ATSF San Diegan EMD F7 (1968), displaying the "SANTA FE" in black Railroad Roman letters along each side

ATSF San Diegan EMD F7 (1968), displaying the "SANTA FE" in black Railroad Roman letters along each side Santa Fe #98, an EMD FP45 decked out in Warbonnet colors, including the traditional "cigar band" nose emblem

Santa Fe #98, an EMD FP45 decked out in Warbonnet colors, including the traditional "cigar band" nose emblem Santa Fe #681 in Sealy Texas, June 2001

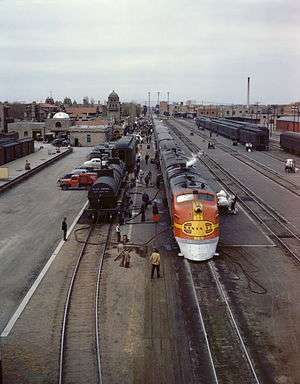

Santa Fe #681 in Sealy Texas, June 2001 The L.A.-bound Super Chief gets its 5-minute pit-stop service in Albuquerque, 1943

The L.A.-bound Super Chief gets its 5-minute pit-stop service in Albuquerque, 1943 ATSF 9542 in Kodachrome leads other locomotives in Yellowbonnet (1990)

ATSF 9542 in Kodachrome leads other locomotives in Yellowbonnet (1990)

Ferry service

Santa Fe maintained and operated a fleet of three passenger ferry boats (the San Pablo, the San Pedro, and the Ocean Wave) that connected Richmond, California with San Francisco by water. The ships traveled the eight miles between the San Francisco Ferry Terminal and the railroad's Point Richmond terminal across San Francisco Bay. The service was originally established as a continuation of the company's named passenger train runs such as the Angel and the Saint. The larger two ships (the San Pablo and the San Pedro) carried Fred Harvey Company dining facilities.

Rival SP owned the world's largest ferry fleet (which was subsidized by other railroad activities), at its peak carrying 40 million passengers and 60 million vehicles annually aboard 43 vessels. Santa Fe discontinued ferry service in 1933 due to the effects of the Great Depression and routed their trains to Southern Pacific's ferry terminal in Oakland. The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge opened in 1936, initiating a slow decline in demand for SP's ferry service, which was eventually discontinued circa 1958; starting in 1938, Santa Fe passenger trains terminated near San Pablo Avenue in Oakland/Emeryville, with passengers for San Francisco boarding buses that used the new bridge.

Atlas Shrugged

In 1946, the writer Ayn Rand met with Lee Lyles, assistant to the president of the Santa Fe, as part of her research for the novel Atlas Shrugged whose plot centers in a large railway company.

The Journals of Ayn Rand, published in 1997 based on notes left after her death, preserve a list of detailed questions which Rand put to Lyles about the company's administrative structure and its practices in various situations and conditions. Later notes in the same journals show that Rand assigned to various characters in her book administrative titles in the book's fictional railway company, modeled on those in the Santa Fe Railway, and adjusted the actions which they are depicted as taking in various situations on the basis of what Lyles told her would be plausible acts for railway executives in similar situations.[22]

See also

![]()

- ATSF 3460 class

- Beep (locomotive)

- CF7

- Corwith Yards, Chicago

- EMD F45

- EMD SDF40-2

- Christine Gonzalez

- David L. Gunn

- History of rail transportation in California

- List of defunct railroads of North America

- Santa Fe 3415 – A restored Pacific type steam locomotive

- Santa Fe 5000

- Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch

- Santa Fe–Southern Pacific merger

- SD26

- Super C

- There Goes a Train

References

- "Santa Fe Pacific Corporation | Encyclopedia.com". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- Drury, George H. (1992). The Train-Watcher's Guide to North American Railroads: A Contemporary Reference to the Major railroads of the U.S., Canada and Mexico. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 37–42. ISBN 978-0-89024-131-8.

- "The Birth of The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, by Joseph W. Snell and Don W. Wilson, Summer 1968". Kancoll.org. 1968-01-17. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- Staff (15 January 1890). "Railway News". The Railroad Telegrapher. Order of Railroad Telegraphers. p. 24. Retrieved 2015-08-11 – via Newspapers.com.

- Walt Disney's Railroad Story, by Michael Broggie, 1997. Page 273. Via Chronology of Disneyland Theme Park: 1952-1955.

- "Western Pacific Railroad Museum - Southern Pacific 2873". Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- Pittman, Russell W. (1990). "Railroads and Competition: The Santa Fe/Southern Pacific Merger Proposal". The Journal of Industrial Economics. 39 (1): 25–46. doi:10.2307/2098366. JSTOR 2098366.

- The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway and Auxiliary Companies – Annual Meetings, and Directors and Officers; January 1, 1902. Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway Company. 1902. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- "John Shedd Reed, rail executive". San Jose Mercury News. Associated Press. 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- "Santa Fe Joining Amtrack". Brownsville Herald. April 21, 1971. p. 2. Retrieved August 12, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- Santa Fe timetable, March 1971 http://www.streamlinerschedules.com/concourse/track8/grandcanyon197104.html

- Bryant Jr. (1974), p. 228.

- "Photo of the Day: Santa Fe 2-10-2". Classic Trains. September 24, 2017. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- "Restoring AT&SF 2926 – official website". New Mexico Steam Locomotive and Railroad Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 15, 2019. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- "Division Point Inc". Division Point Inc. Archived from the original on October 18, 2006.

- "Division Point Inc". Division Point Inc. Archived from the original on October 18, 2006.

- U.S. Patent D106,920

- "Photo: ATSF 304A Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (ATSF) EMD F7(B) at Los Angeles, California by Craig Walker". Railpictures.net. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- "Photo: ATSF 300B Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (ATSF) EMD F7(B) at Los Angeles, California by Craig Walker". Railpictures.net. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- "Photo: ATSF M160 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (ATSF) Gas Electric Doodlebug at Dallas, Texas by Ellis Simon". Railpictures.net. 2005-03-13. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- Brian Solomon (2005). Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway. Voyageur Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-7603-2108-9.

- Journals of Ayn Rand, Entries for August 26–28, 1946

Further reading

- Berkman, Pamela, ed. (1988). The History of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe. Brompton Books Corp., Greenwich, CT. ISBN 978-0-517-63350-2.

- Bryant Jr., Keith L. (1974). History of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. Trans-Anglo Books, Glendale, CA. ISBN 978-0-8032-6066-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Cosmopolitan (February 1893), The Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe. Retrieved May 10, 2005.

- Darton, N. H. (1915). Guidebook of the Western United States, Part C. The Santa Fe Route. USGS Bulletin 613.

- Donaldson, Stephen E. & William A. Myers (1989). Rails through the Orange Groves, Volume One. Trans-Anglo Books, Glendale, CA. ISBN 978-0-87046-088-3.

- Donaldson, Stephen E. & William A. Myers (1990). Rails through the Orange Groves, Volume Two. Trans-Anglo Books, Glendale, CA. ISBN 978-0-87046-094-4.

- Duke, Donald; Kistler, Stan (1963). Santa Fe...Steel Rails through California. Golden West Books, San Marino, CA.

- Duke, Donald (1997). Santa Fe: The Railroad Gateway to the American West, Volume One. Golden West Books, San Marino, CA. ISBN 978-0-87095-110-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duke, Donald (1990). Santa Fe: The Railroad Gateway to the American West, Volume Two. Golden West Books, San Marino, CA. ISBN 978-0-87095-113-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duke, Donald. Fred Harvey, civilizer of the American Southwest (Pregel Press, 1995); The passenger trains stopped for meals at Fred Harvey restaurants.

- Dye, Victoria E. All Aboard for Santa Fe: Railway Promotion of the Southwest, 1890s to 1930s (University of New Mexico Press, 2007).

- Foster, George H. & Peter C. Weiglin (1992). The Harvey House Cookbook: Memories of Dining along the Santa Fe Railroad. Longstreet Press, Atlanta, GA. ISBN 978-1-56352-357-1.

- Frailey, Fred W. (1998). Twilight of the Great Trains, p. 108. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. ISBN 0 89024 178 3.

- Richard H. Frost, The Railroad and the Pueblo Indians: The Impact of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa fe on the Pueblos of the Rio Grande, 1880-1930. 2016, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1-607-81440-5

- Glischinski, Steve (1997). Santa Fe Railway. Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International. ISBN 978-0-7603-0380-1.

- Goen, Steve Allen (2000). Santa Fe in the Lone Star State

- Hendrickson, Richard H. (1998). Santa Fe Railway Painting and Lettering Guide for Model Railroaders, Volume 1: Rolling Stock. The Santa Fe Railway Historical and Modeling Society, Inc., Highlands Ranch, CO.

- Marshall, James Leslie. Santa Fe: the railroad that built an empire (1945).

- Pelouze, Richard W. (1997). Trademarks of the Santa Fe Railway and Peripheral Subjects. The Santa Fe Railway Historical and Modeling Society, Inc., Highlands Ranch, CO. ISBN 9781933587066.

- Porterfield, James D. (1993). Dining by Rail: the History and Recipes of America's Golden Age of Railroading. St. Martin's Press, New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-312-18711-8.

- Pratt School of Engineering, Duke University (2004), Alumni Profiles: W. John Swartz. Retrieved May 11, 2005.

- Santa Fe Railroad (1945), Along Your Way, Rand McNally, Chicago, Illinois.

- Santa Fe Railroad (November 29, 1942), Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway System Time Tables, Rand McNally and Company, Chicago, Illinois.

- Serpico, Philip C. (1988). Santa Fé: Route to the Pacific. Hawthorne Printing Co., Gardena, CA. ISBN 978-0-88418-000-5.

- Solomon, Brian. Santa Fe Railway (Voyageur Press, 2003).

- Waters, Lawrence Leslie (1950). Steel Trails to Santa Fe. University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, Kansas.

- Snell, Joseph W. and Don W. Wilson, "The Birth of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad," (Part One) Kansas Historical Quarterly (1968) 34#2 pp 113–142. online

- Snell, Joseph W. and Don W. Wilson, "The Birth of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad," (Part Two) Kansas Historical Quarterly (1968) 34#3 pp 325–356 online

- White, Richard (2011). Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06126-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. |

- "Along Your Way", 1946 edition

- Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe photos and other documents on Kansas Memory, the digital portal of the Kansas Historical Society (over 2800 AT&SF items)

- Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Company Records at the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas

- Russell Crump's Santa Fe Archives — a very extensive set of resources for Santa Fe history.

- Santa Fe All-Time Steam Roster

- Santa Fe Preserved Locomotives

- Santa Fe Preserved Passenger Cars

- Santa Fe Railway Historical and Modeling Society official website

- "Diesel Locomotives" article from the May 18, 1947 issue of Life Magazine featuring the Santa Fe fleet.

- James William Steele. Rand, McNally & Co.'s new overland guide to the Pacific Coast. Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1888. Illustrated guide to the Santa Fe trip circa 1888.

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway

- Atchison, Topeka and Sante Fe Railroad Records at Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory