2 Kings 1

2 Kings 1 is the first chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1][2] The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE.[3] This chapter focuses on the Israel king Ahaziah, the son of Ahab, and the acts of Elijah the prophet who rebuked the king and prophesied the king's death.[4]

| 2 Kings 1 | |

|---|---|

← 1 Kings 22 | |

The pages containing the Books of Kings (1 & 2 Kings) Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | Second Book of Kings |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 4 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 12 |

Text

This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language and since the 16th century is divided into 18 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[5]

There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BCE. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century) and Codex Marchalianus (Q; Q; 6th century).[6][lower-alpha 1]

Analysis

The second book of Kings begins with a chapter featuring the prophet Elijah, whose stories occupy the last part of the first book of Kings (1 Kings). In this final story of confrontation with a monarch, Elijah takes on King Ahaziah of Israel whose reign was introduced in the ending verses of 1 Kings (1 Kings 22:52-54).[8]

The artificial separation of this episode of Elijah from those in the previous book resulted from the Septuagint's division of the Hebrew book of Kings into two parts, whereas the Jewish Hebrew text tradition continued to consider Kings as one book until the Bamberg Rabbinic Bible of 1516.[8] This makes 2 Kings begin with a sick king (Ahaziah) in his deathbed, just as 1 Kings (David), where both Ahaziah and David received prophets with quite different results.[9] Although Elijah is fully capable of raising the dead (1 Kings 17:17-24), Ahaziah seeks help elsewhere, so instead of being healed, he was prophesied by Elijah to die in his current bed.[9]

The abruptness of the beginning of 2 Kings can also be seen its very first verse about Moab's rebellion against Israel after the death of Ahab, which seems unrelated to the story of Ahaziah and Elijah that follows it; the rebellion will be dealt in chapter 3, where it starts with the verbatim "repetitive resumption" (Wiederaufnahme) of 2 Kings 1:1 in 2 Kings 3:5.[10] However, this opening episode of 2 Kings serves several important functions: looking backwards to summarize the personality and behavioral traits of Elijah, while at the same time anticipating the future anti-Baal crusade by Jehu who would destroy the Omride dynasty.[11]

This narrative is one of four in 1–2 Kings in which a prophet delivers an oracle to a dying king, placing Elijah in a "type-scene" associated with each major prophet in the book (Ahijah in 1 Kings 14:1–18; Elisha in 2 Kings 8:7–15; Isaiah in 2 Kings 20:1–11), thus linking him into a prophetic chain.[11] The differences from the common pattern are the threefold repetition of the oracle (verses 3b-4, 6, 16) and the confrontations between Elijah and the three captains of the king.[11]

Structure

The main narrative of this chapter contains parallel elements that create structural symmetry:[12]

- A Ahaziah's illness and inquiry (1:2)

- B Angel of YHWH sends Elijah to messengers with prophecy (1) (1:3–4)

- C Messengers deliver prophecy (2) to Ahaziah (1:5–8)

- X Three captains confront Elijah (1.9–14)

- C Messengers deliver prophecy (2) to Ahaziah (1:5–8)

- B' Angel of YHWH sends Elijah to Ahaziah (1:15)

- C' Elijah delivers prophecy (3) to Ahaziah (1:16)

- B Angel of YHWH sends Elijah to messengers with prophecy (1) (1:3–4)

- A' Ahaziah's death (1:17)

Opening verse (1:1)

- Then Moab rebelled against Israel after the death of Ahab.[13]

- Cross reference: 2 Kings 3:5

This statement about Moab's rebellion in the opening verse of 2 Kings is elaborated in 2 Kings 3:5ff,[14] and supported by the information in the Mesha Stele (see detailed comparisons in chapter 3).[4]

Moab in the Trans-Jordan region was incorporated into Israel by King David, who has family connections with the people of that land (Ruth 4), mentioned only briefly in 1 Kings 11:7 as a client state of Israel during the days of David and Solomon, then ruled by the Northern Kingdom of Israel during the reigning period of the Omrides.[14]

Ahaziah's illness and inquiry (1:2)

- And Ahaziah fell down through a lattice in his upper chamber that was in Samaria, and was sick: and he sent messengers, and said unto them, Go, enquire of Baalzebub the god of Ekron whether I shall recover of this disease.[15]

- "Go, enquire": Ahaziah calls for an oracle (cf. 1 Kings 14), though from Baal rather than YHWH.[4]

- "Baalzebub": two qualities of this Syro-Palestinian god, Baal, are mentioned here: as the patron-god of the Philistine city Ekron and the accompaniment of a second name, Zebub, meaning 'fly' (insect), revealing that the oracles of this god 'were carried out to the sound of humming'.[4] The name "Baalzebub" ("lord of the flies") is found only here in the Hebrew Bible, but referred to several times in the New Testament (e.g., Matthew 10:25; 12:24). It may be a pejorative rendering of ba'al zebal ("Baal the Prince"), a 'common epithet for Baal in Ugaritic literature'.[11]

Elijah interferes (1:3–16)

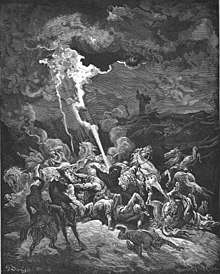

The oracular consultation that Ahaziah requested did not take place due to Elijah's interference in the name of YHWH, following the explicit order of an 'angel of the LORD' (verses 3–4) and three (fifty-strong) army divisions are unable to stop him (verses 9-16). Thematically similar to 1 Kings 18, Elijah's mission to promote the exclusive worship of YHWH in Israel suits his name ('My God is YHWH!'). Ahaziah only came to know who the prophet was by the description of Elijah's appearance, and aside from his mantle (cf. 2 Kings 2:13), Elijah's recognizable feature seems to be his sudden showing up 'precisely when he is not expected or wanted, fearlessly saying what was to be said in the name of his God' (cf. 1 Kings 18:7; 21:17–20).[4]

Death of Ahaziah (1:17–18)

In Ahaziah's life and death, the history of the house of Ahab is parallel to that of the house of Jeroboam I. A man of God from Judah prophesied the end of Jeroboam's family (1 Kings 13), then Jeroboam's son Abijah was sick and died before the dynasty ended. Likewise, after the destruction of Ahab's family was prophesied, Ahab's son, Ahaziah, died when the dynasty was still intact. However both dynasties fell during the reign of a subsequent son.[14]

Verse 17

- So he died according to the word of the Lord which Elijah had spoken

- Then Jehoram reigned in his place in the second year of Jehoram son of Jehoshaphat, king of Judah, because he had no son.[16]

- "Jehoram reigned in his place": This is Jehoram the brother of Ahaziah and another son of Ahab. His name is written as "Joram" in 1 Chronicles 3:11; 26:24.[17] 2 Kings 3:1 records that he "reigned twelve years", which, based on Thiele-McFall's calculation, span from between April and September 852 BCE until his death between April and September 841 BCE.[18]

- "The second year of Jehoram son of Jehoshaphat, king of Judah": According to Thiele's chronology,[19] this is the period of "co-regency" on the throne of Judah with his father Jehoshaphat,[18] who was then in his 18th year of sole reign as noted in 2 Kings 3:1.[lower-alpha 2] In Thiele-McFall's calculation, this time point falls between April and September 852 BCE.[21]

See also

- Related Bible parts:1 Kings 22, 2 Kings 3, 2 Chronicles 30, Isaiah 20, Zechariah 13, Matthew 3, Matthew 11, Hebrews 11

Notes

- The whole book of 2 Kings is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[7]

- The 18th year of Jehoshaphat's sole reign is the same as the 20th year of his reign from the beginning of his co-regency with his father, Asa, which is later counted into his total reign of 25 years.[20]

References

- Halley 1965, p. 200.

- Collins 2014, p. 285.

- McKane 1993, p. 324.

- Dietrich 2007, p. 248.

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 35-37.

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 73-74.

-

- Cohn 2000, p. 3.

- Leithart 2006, p. 165.

- Cohn 2000, pp. 3–4.

- Cohn 2000, p. 4.

- Cohn 2000, pp. 4–5.

- 2 Kings 1:1 KJV

- Leithart 2006, p. 166.

- 2 Kings 1:2 KJV

- 2 Kings 1:17 MEV

- Note on 2 Kings 1:17 in MEV

- McFall 1991, no. 22.

- Thiele, Edwin R., The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951; 2d ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965; 3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983). ISBN 0-8254-3825-X, 9780825438257

- Tetley 2005, p. 110.

- McFall 1991, no. 23.

Sources

- Cohn, Robert L. (2000). Cotter, David W.; Walsh, Jerome T.; Franke, Chris (eds.). 2 Kings. Berit Olam (The Everlasting Covenant): Studies In Hebrew Narrative And Poetry. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814650547.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, John J. (2014). "Chapter 14: 1 Kings 12 – 2 Kings 25". Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fortress Press. pp. 277–296. ISBN 9781451469233.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288810.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dietrich, Walter (2007). "13. 1 and 2 Kings". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 232–615. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leithart, Peter J. (2006). 1 & 2 Kings. Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1587431258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McFall, Leslie (1991), "Translation Guide to the Chronological Data in Kings and Chronicles" (PDF), Bibliotheca Sacra, 148: 3-45, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-19CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKane, William (1993). "Kings, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 409–413. ISBN 978-0195046458.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tetley, M. Christine (2005). The Reconstructed Chronology of the Divided Kingdom (illustrated ed.). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060729.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Jewish translations:

- Melachim II - II Kings - Chapter 1 (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- 2 Kings Chapter 1. Bible Gateway