2 Kings 14

2 Kings 14 is the fourteenth chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1][2] The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE.[3] This chapter records the events during the reigns of Amaziah the son of Joash, king of Judah, as well as of Joash, and his son, Jeroboam (II) in the kingdom of Israel.[4] The narrative is a part of a major section 2 Kings 9:1–15:12 covering the period of Jehu's dynasty.[5]

| 2 Kings 14 | |

|---|---|

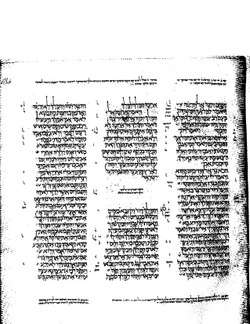

The pages containing the Books of Kings (1 & 2 Kings) Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | Second Book of Kings |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 4 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 12 |

Text

This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language. It is divided into 29 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century[lower-alpha 1]), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[7]

There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BCE. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century) and Codex Marchalianus (Q; Q; 6th century).[8][lower-alpha 2]

Analysis

This chapter as a whole (as many other parts of 1–2 Kings) functions as a ‘parable and allegory’, and in particular includes a ‘proverb’ given by Jehoash king of Israel to Amaziah king of Judah (14:9–10).[10] Some examples of the parabolic or allegoric style are provided in form of the ‘history repeating itself’. During the time of Rehoboam the son of Solomon, after the division of the kingdom of Israel (1 Kings 12:21–24), Shisak the king of Egypt plundered the temple in Jerusalem (1 Kings 14:25–28) and this event has a similar pattern in this chapter when Jehoash the king of Israel plundered the temple and broke down a large portion of the walls of the city of Jerusalem (2 Kings 14:13–14).[11] Another parallel commences at the end of the chapter when another Jeroboam started to reign in Israel and the subsequent chapters reveal a ‘providential chronological and historical symmetry’ with the first Jeroboam.[11] While Jeroboam I initiated the separation of the united kingdom to form the northern kingdom of Israel, Jeroboam II started the countdown to the end of this northern kingdom.[11] There is an indication that the kingdoms were reunited briefly under Jehu's dynasty is supported by some details in Jeroboam II's reign: the Israel king extended the borders of his kingdom from Hamath in the north to the Sea of the Arabah in the south, far into the territory of the kingdom of Judah (14:25), which ‘echoes the ideal boundaries of the original united kingdom’ (1 Kings 8:65).[12] 2 Kings 14:28 can also be translated as “he recovered Damascus and Hamath to Judah in Israel” as if Jeroboam II recovered the territory of Judah back to “the kingdom of Israel”, forming a (semi)united kingdom.[12]

Amaziah, king of Judah (14:1–22)

The historical records of Amaziah the king of Judah might be taken exclusively from the Judean annals. He took revenge for his father's murder (verse 5, cf. 2 Kings 12:20–21; verses 6–7 are an educated scribe's addition according to Deuteronomy 24:16, cf. also Ezekiel 18) only to fall victim to murder himself (verses 19–20). Amaziah also defeated the Edomites in the Arabah ("Valley of Salt", verse 7, cf. 2 Samuel 8:13,[13] also verse 22), highlighting a struggle between Edom and Judah at the time (cf. 1 Kings 22:48; 2 Kings 16:6). However, the most detail is about the war with Israel which Amaziah initiated but ultimately lost (verses 8–14).[14] Amaziah outlived Joash by at least fifteen years, but his violent death in the reign of Jeroboam II, the son of Joash, (verses 15–16) probably still related back to the events of his defeat. Amaziah's successor, Azariah (later, Uzziah), was chosen by 'the people of Judah' (verse 21), probably meaning 'the people of the land', who had an 'increasingly influential role in Judean politics' since the end of Athaliah's reign.[14] Azariah (2 Kings 15:1–7) managed to consolidate his father's conquest of Edom by claiming the port of Elath for Judah (cf. 1 Kings 9:26).[15]

Verse 1

- In the second year of Joash son of Jehoahaz, king of Israel, Amaziah the son of Joash, king of Judah, became king[16]

- "In the 2nd year of Joash the son of Jehoahaz": According to Thiele's chronology,[17] following "accession year method", Amaziah the son of Joash of Judah became the 9th king of Judah starting between April and September 796 BCE, because the 2nd year Joash the son of Jehoahaz, the king of Israel, started in April 796 BCE.[18]

- "Jehoahaz": written in Hebrew as ‘’Joahaz’’ which is an alternate form of Jehoahaz.[19]

- "Joash, king of Judah": (cf. 2 Kings 12:21), a different person from Joash of Israel, the son of Jehoahaz, mentioned earlier in the verse.[20]

War between Israel and Judah

Historical records show that Adad-nirari III of Assyria claims a successful westward campaign in 806 BCE, defeating, among others, 'Omri-Land' (the name Assyrian uses for Israel) and also Edom (ANET 281-2). This might encourage Amaziah to wage wars against Edom and Israel. He was successful to defeat Edom, but he miscalculated the strength of Israel.[14] Joash the king of Israel, had warned Amaziah, using a parable: “A thistle in Lebanon sent a message to a cedar in Lebanon, 'Give your daughter to my son in marriage.' Then a wild beast in Lebanon came along and trampled the thistle underfoot. You have indeed defeated Edom and now you are arrogant. Glory in your victory, but stay at home! Why ask for trouble and cause your own downfall and that of Judah also?"[21] However, Amaziah insisted on the war. Joash's army defeated Amaziah's at Beth-shemesh, on the borders of Dan and Philistia, then plundered Judah's palace and the temple, also broke down 200 meters of the 'particularly sensitive northern wall of Jerusalem', leaving the city defenseless.[14]

Jeroboam (II), king of Israel (13:23-29)

Jeroboam's reign outshines that of Joash, his father, as the northern kingdom enjoys a glorious period, when Aram-Damascus was ensnared between Israel and Assyria (cf. verse 28), that apparently allowed Jeroboam to control the territories northwards to Hamath on the Orontes, and also to the east and south as far as the Dead Sea (verse 25). This implies a hegemony over Judah, or at least the Jordan valley and the regions east of the Jordan, Gilead and Gad. The Book of Amos provides highlights to Israel's momentary political success: 'they were proud of the land they gained (Amos 6:13), the higher classes at least enjoyed the incoming wealth (Amos 6:4—6), the people believed they were God's favorites (Amos 6:1)', although Amos prophesied that this period of happiness would be short.[14] The prophet Jonah ben Amittai was active in Israel at the time and had forecast Jeroboam's successes, so this can be seen as God's will, like other previous political events, 'according to the word of the LORD, which he spoke by the hand of...' (cf. the 'underlying rule'in Deuteronomy 18:21–22 and the examples in 1 Kings 15:29; 16:12; 22:38; 2 Kings 10:17). It is thought that God saw how Israel had suffered so much in the past, so God took pity, as connected to 13:5–6, 23–5. The mention of Jonah supports the historical basis of his claim in the Book of Jonah that God's mercy extended to peoples beyond Israel, including Assyria.[22]

Verse 23

- In the fifteenth year of Amaziah the son of Joash king of Judah Jeroboam the son of Joash king of Israel began to reign in Samaria, and reigned forty and one years.[23]

- "'In the 15th year of Amaziah": According to Thiele's chronology, following the "accession year method", Jeroboam the son of Joash became the co-regent on the throne of Israel with his father in April 793 BCE then reign alone after his father's death starting between September 782 BCE and April 781 BCE.[24]

- "41 years": according to Thiele's chronology, following the "accession year method", are the years of Jeroboam's reign starting from the co-regency with his father in April 793 BCE, to his death a while before Tishrei (September) 753 BCE.[24] The co-regency is initially suggested in Seder Olam[25] and also by Kimhi.[26] According to McFall, Jeroboam died between the month of Elul (the 6th month in the Hebrew ecclesiastical calendar; August/September) and Tishrei (the 7th month; September/October) 753 BCE, to be immediately succeeded by his son, Zechariah, which was in the 38th year of Uzziah (=Azariah), the king of Judah.[27]

Archeology

The excavation at Tell al-Rimah yields a stele of Adad-nirari III which mentioned "Jehoash the Samarian"[28][29] and contains the first cuneiform mention of Samaria by that name.[30] The inscriptions of this "Tell al-Rimah Stele" may provide evidence of the existence of King Jehoash (=Joash) of Israel, attest to the weakening of Syrian kingdom (cf. 2 Kings 13:5), and show the vassal status of the northern kingdom of Israel to the Assyrians.[31]

A postulated image of Joash is reconstructed from plaster remains recovered at Kuntillet Ajrud.[32][33] The ruins were from a temple built by the northern Israel kingdom when Jehoash of Israel gained control over the kingdom of Judah during the reign of Amaziah of Judah.[34]

See also

- Related Bible parts: 2 Kings 13, 2 Chronicles 24, 2 Chronicles 25, Jonah 1, Matthew 12, Matthew 16, Luke 1

Notes

- Since 1947 the current text of Aleppo Codex is missing 2 Kings 14:21–18:13.[6]

- The whole book of 2 Kings is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[9]

References

- Halley 1965, p. 201.

- Collins 2014, p. 288.

- McKane 1993, p. 324.

- Dietrich 2007, pp. 257–258.

- Dietrich 2007, p. 253.

- P. W. Skehan (2003), "BIBLE (TEXTS)", New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2 (2nd ed.), Gale, pp. 355–362

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 35-37.

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 73-74.

-

- Leithart 2006, p. 237.

- Leithart 2006, p. 238.

- Leithart 2006, p. 240.

- Coogan 2007, p. 554–555 Hebrew Bible.

- Dietrich 2007, p. 257.

- Coogan 2007, p. 555 Hebrew Bible.

- 2 Kings 14:1 MEV

- Thiele, Edwin R. (1951). The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (1st ed.). New York: Macmillan.

- McFall 1991, no. 36.

- Note [a] on 2 Kings 14:1 in NET Bible

- Note [b] on 2 Kings 14:1 in NET Bible

- 2 Kings 14:9-10; 'Joash' is a variation of 'Jehoash'. The Anchor Bible Dictionary, Vol III, 1992. Freedman, David Noel., ed., New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19361-0 pp. 857-858

- Dietrich 2007, p. 258.

- 2 Kings 14:23 KJV

- McFall 1991, no. 39.

- Seder Olam Rabbah, chapter 27 "Jehu to Uzziah". English quotation: "...That he [Jeroboam] ruled during the lifetime of his father."

- Thiele 1951, p. 115.

- McFall 1991, no. 40.

- Shea, William H. (1978). "Adad-Nirari III and Jehoash of Israel". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 30 (2): 101–113. doi:10.2307/1359970. JSTOR 1359970.

- Tell al-Rimah Stela (797 BCE): inscription by Assyrian king Adad-Nirari III, in which he describes his successes in the west. Livius.org. Quote: "...[4] I received 2,000 talents of silver, 1,000 talents of copper, 2,000 talents of iron, 3,000 linen garments with multicolored trim - the tribute of Mari' - of the land of Damascus. I received the tribute of Jehoash the Samarian, of the Tyrian ruler and of the Sidonian ruler."

- Page, Stephanie (1968). "A Stela of Adad-nirari III and Nergal-ereš from Tell al Rimah". Iraq. 30 (2): 139–153. doi:10.2307/4199848. JSTOR 4199848.

- "Tell al-Rimah Stele: King Jehoash Found!" Assyrian inscriptions prove Israel's deliverance from the Syrians through King Jehoash. Warren Reinsch. Watch Jerusalem, June 27, 2019.

- Beck, Pirhiya (1982). "The Drawings from Horvat Teiman (Kuntillet 'Ajrud)". Tel Aviv. 9: 3–68. doi:10.1179/033443582788440827.

- Ornan, Tallay (2016). "Sketches and Final Works of Art: The Drawings and Wall Paintings of Kuntillet 'Ajrud Revisited". Tel Aviv. 43: 3–26. doi:10.1080/03344355.2016.1161374.

- Nir Hasson. A strange drawing found in Sinai could undermine our entire idea of Judaism: Is that a 3,000-year-old picture of god, his penis and his wife depicted by early Jews at Kuntillet Ajrud?. Haaretz.com. April 4, 2018

Sources

- Cohn, Robert L. (2000). Cotter, David W.; Walsh, Jerome T.; Franke, Chris (eds.). 2 Kings. Berit Olam (The Everlasting Covenant): Studies In Hebrew Narrative And Poetry. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814650547.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, John J. (2014). "Chapter 14: 1 Kings 12 – 2 Kings 25". Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fortress Press. pp. 277–296. ISBN 9781451469233.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288810.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dietrich, Walter (2007). "13. 1 and 2 Kings". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 232–615. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leithart, Peter J. (2006). 1 & 2 Kings. Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1587431258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McFall, Leslie (1991), "Translation Guide to the Chronological Data in Kings and Chronicles" (PDF), Bibliotheca Sacra, 148: 3–45, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-19CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKane, William (1993). "Kings, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 409–413. ISBN 978-0195046458.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Jewish translations:

- Melachim II - II Kings - Chapter 14 (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- 2 Kings chapter 14. Bible Gateway