2 Kings 16

2 Kings 16 is the sixteenth chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1][2] The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE.[3] This chapter records the events during the reign of Ahaz, the king of Judah.[4]

| 2 Kings 16 | |

|---|---|

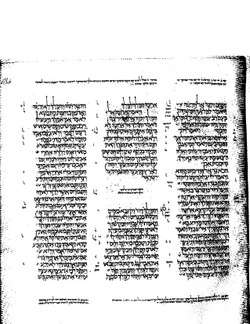

The pages containing the Books of Kings (1 & 2 Kings) Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | Second Book of Kings |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 4 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 12 |

Text

This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language. It is divided into 20 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[5][lower-alpha 1]

There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BCE. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century) and Codex Marchalianus (Q; Q; 6th century).[7][lower-alpha 2]

Analysis

This chapter is organized chiastically:[9]

- A formulaic introduction (16:1–4)

- B threat to Jerusalem and bribe of Tiglath-pileser (16:5–9)

- C state visit to Damascus (16:10–11: altar)

- D Ahaz ministers at the altar (16:12–14)

- C' continuing worship at the altar (16:15–16)

- C state visit to Damascus (16:10–11: altar)

- B' tribute to Tiglath-pileser and plunder of temple (16:17–18)

- B threat to Jerusalem and bribe of Tiglath-pileser (16:5–9)

- A' summary (16:19–20)

Centering on Ahaz's interest in the altar of Damascus, the narrator highlights the typology of this passage, contrasted the images of Solomon and Jeroboam at altars in the First Book of Kings (1 Kings 8, 12:32–33), to Ahaz standing before the altar, a replica of that in Damascus, becoming 'another Jeroboam', setting up an alternative worship to that of Solomon's temple, so Judah repeats the sin of Israel and would suitably be doomed at the end.[9]

Ahaz is judged more severely than any king of Judah other than Manasseh, as he followed the ways of Israel's kings rather than David's. Ahaziah of Judah did the same (2 Kings 8:27), but with the "excuse" of being part of Ahab's family, whereas no excuse is given for Ahaz.[9] Going further that imitating Israel's alternative worship, Ahaz revived the customs of the Canaanite nations that Israel had originally displaced (16:3) causing 'idolatrous shrines sprinkled throughout the land'.[9] Meanwhile, the kingdoms Israel and Aram, in alliance against Assyria, attacked Ahaz from the north (Isaiah 7), and Rezin of Syria took a town of Judah (2 Kings 16:6), 'driving the inhabitants into a mini-exile'.[9] Not turning to YHWH, Ahaz turned to Tiglath-Pileser III for help and declared himself as the "servant and son" of the Assyrian king (16:7). The Assyrians ransacked Damascus and drove the Arameans into exile. Thus, both Israel and Judah were pressured into 'compromising alliances with Gentiles': Israel allied with Aram, 'its traditional enemy', while Judah allied with Assyria, bringing the image of "the sons of God 'marrying' the daughters of men" (Genesis 6:1-4), and then "a flood" of Gentiles swept 'both Judah and Israel into exile' (Genesis 6-9).[9]

Ahaz and the Syro-Ephraimite War (16:1–9)

The introductory regnal account of Ahaz emphasizes on his wickedness,[10] that despite his encounters with the prophet Isaiah (Isaiah 7:1–9:6),[4][11] he acted like the kings of Israel (cf. 2 Kings 8:18), failed to follow David's example (cf. 2 Kings 14:3; 1 Kings 15:11).[10] The evidence is that the "abominable" worship practices of the Canaanites (cf. Deuteronomy 20:18) including "passing his son through fire" (verses 3–4; cf Deuteronomy 12:31; 18:10; 2 Kings 17:17), tying to the practices of Jeroboam (1 Kings 14:24) and Manasseh (2 Kings 21:2–6).[12][13] Facing the attack of the Syro-Ephraimitic forces, Ahaz didn't accept the advice of Isaiah to seek YHWH's protection, but appealed to Tiglath-Pileser, who didn't need Ahaz's invitation to attack Aram. Ahaz's approach made Israel obligated to the Assyrians, whereas Tiglath-Pileser didn't feel the same way and even imposed further tribute on Ahaz for the rescue.[14]

Verse 1

- In the seventeenth year of Pekah the son of Remaliah, Ahaz the son of Jotham, king of Judah, began to reign.[15]

- Cross references: 2 Chronicles 28:1

- "In the 17th year of Pekah": According to Thiele's chronology,[16] Ahaz became co-regent with his father, Jotham, in the kingdom of Judah, in September 735 BCE and became a sole king between September 732 BCE and September 731 BCE,[17] overlapping Pekah's 20th (and last) year,[18] and Jotham's 20th year.[19]

Verse 2

- Ahaz was twenty years old when he became king, and he reigned sixteen years in Jerusalem; and he did not do what was right in the sight of the Lord his God, as his father David had done.[20]

- "Reigned 16 years": according to Thiele's chronology, Ahaz became co-regent in September 735 BCE, then as sole king for 16 years between September 732 BCE and September 731 BCE until he died a few weeks (or days) before Nisan 715 BCE.[21]

Verse 5

- Then Rezin king of Syria and Pekah son of Remaliah king of Israel came up to Jerusalem to war: and they besieged Ahaz, but could not overcome him.[22]

- Cross reference: Isaiah 7:1[23]

The Syro-Ephraimitic army could not afford to lay prolonged siege of Jerusalem while Aram's border was open to Assyrians' assault.[14] That was foreseen by Isaiah when giving his advice to Ahaz (Isaiah 7-9).[14]

Ahaz paganizes the Temple (16:10–20)

This section focuses on the new altar that Ahaz made following the design of the one he saw in Damascus, when he went there to meet (perhaps to give his oath of allegiance) to Tiglath-pileser who had set up his headquarters in that city.[4] The new altar took the spot of the bronze one commissioned by Solomon (1 Kings 8:64), which is shifted to the north side of the new one, and took over its functions for regular offerings (cf. Numbers 29:39). The heavy bronze instruments that were installed by Solomon in the temple court (1 Kings 7:27—39) and other structures in the temple were changed by Ahaz 'because of the king of Assyria".[4] The altars on the roof of Ahaz's upper chamber were later destroyed by king Josiah (2 Kings 23:12.[24]

Archaeology

Ahaz

Much of Ahaz's foreign policy is not known from the Books of Kings, but from the Book of Isaiah and Assyrian inscriptions (ANET 282–284[25]). The " Nimrud Tablet K.3751", which describes the first 17 years of Tiglath-Pileser III's reign, contains first known archeological reference to Judah (Yaudaya or KUR.ia-ú-da-a-a) and the name of "Ahaz" (written as "Jeho-ahaz"), along with his tributes to the Assyrian king in gold and silver.[26]

Several bullae bearing the name of Ahaz have been found:

- a royal bulla with the inscription: “Belonging to Ahaz (son of) Jehotam, King of Judah.”[27][28]

- stone seal in scarab (beetle) shape with the inscription: "Belonging to Ushna servant of Ahaz"[29]

- a royal bulla with the inscription: "Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz king of Judah" (between 727–698 BCE).[30]

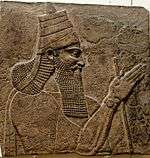

Tiglath-Pileser III

Many inscriptions from the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III, the king of Assyria, have been found, most of them from his ancient palace in Nimrud, ancient Kalhu, including: (1) Annals (arranged chronologically); (2) Summary Inscriptions (arranged in a predominantly geographical pattern); and (3) Miscellaneous Texts (labels, dedicatory inscriptions, as well as other fragments).[31][32]

Rezin

The account of Rezin is found among Tiglath-Pileser's inscriptions, particularly those related to a three-year Assyrian campaign in the Levant from 734-732 BCE, as in the following quote:

- Quote: "In order to save his life, he ("Raḫiānu" or "Rezin") fled alone and entered the gate of his city [like] a mongoose … I surrounded (and) captured [the city ...]ḫādara, the ancestral home of Raḫiānu ("Rezin") of the land Damascus, [the pl]ace where he was born. …Like tell(s) after the Deluge, I destroyed 591 cities of 16 districts of the land Damascus. (RINAP 1, Tiglath-Pileser III 20, l. 8’-17’)[31]

This is comparable to the account in the 2 Kings 16:9:

- And the king of Assyria [Tiglath-Pileser III] hearkened unto him: for the king of Assyria went up against Damascus, and took it, and carried the people of it captive to Kir, and slew Rezin.[33]

Pekah

One annals of Tiglath-Pileser III mentioned Pekah and Hoshea, two last kings of Israel:

- They overthrew their king Pekah (Pa-qa-ḥa) and I placed Hoshea (A-ú-si-ʼ) as king over them. I [Tiglath-Pileser III] received from them 10 talents of gold, 1,000 (?) talents of silver as their [tri]bute, and brought them to Assyria (ANET 284)[34]

This is comparable to the account in 2 Kings 15:30:

- Then Hoshea the son of Elah made a conspiracy against Pekah the son of Remaliah and struck him down and put him to death and reigned in his place, in the twentieth year of Jotham the son of Uzziah.[35]

Notes

- Since 1947 the current text of Aleppo Codex is missing 2 Kings 14:21–18:13.[6]

- The whole book of 2 Kings is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[8]

References

- Halley 1965, p. 201.

- Collins 2014, p. 288.

- McKane 1993, p. 324.

- Dietrich 2007, p. 259.

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 35-37.

- P. W. Skehan (2003), "BIBLE (TEXTS)", New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2 (2nd ed.), Gale, pp. 355–362

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 73-74.

-

- Leithart 2006, p. 246.

- Nelson 1987, p. 223.

- Sweeney 2007, p. 379.

- Nelson 1987, p. 224.

- Fretheim 1997, pp. 189–190.

- Sweeney 2007, p. 380.

- 2 Kings 16:1 ESV

- Thiele, Edwin R., The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951; 2d ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965; 3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983). ISBN 0-8254-3825-X, 9780825438257

- McFall 1991, no. 48.

- McFall 1991, no. 45.

- McFall 1991, no. 47.

- 2 Kings 16:2 NKJV

- McFall 1991, no. 48, 54.

- 2 Kings 16:5 KJV

- Note [c] on 2 Kings 16:5 in NET Bible

- Nelson 1987, p. 227.

- Pritchard 1969, pp. 282–284.

- The Pitcher Is Broken: Memorial Essays for Gosta W. Ahlstrom, Steven W. Holloway, Lowell K. Handy, Continuum, 1 May 1995 Quote: "For Israel, the description of the battle of Qarqar in the Kurkh Monolith of Shalmaneser III (mid-ninth century) and for Judah, a Tiglath-pileser III text mentioning (Jeho-) Ahaz of Judah (IIR67 = K. 3751), dated 734-733, are the earliest published to date."

- "Biblical Archaeology 15: Ahaz Bulla". 12 August 2011.

- First Impression Archived 2017-09-22 at the Wayback Machine: What We Learn from King Ahaz’s Seal by Robert Deutsch

- Ancient Seals From The Babylonian Collection. Library.yale.edu. Accessed June 6, 2020

- Eisenbud, Daniel K. (2015). "First Ever Seal Impression of an Israelite or Judean King Exposed near Temple Mount". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Tadmor, Hayim; Yamada, Shigeo (2011). "The Royal Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III (744-727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (726-722 BC), Kings of Assyria". www.eisenbrauns.org. The Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period 1; Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- Yamada, Shigeo (2012). "The Reign and Inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser III, an Assyrian Empire Builder (744-727 BC)". L’annuaire du Collège de France [Online]. 111 (111): 902–903. doi:10.4000/annuaire-cdf.1803. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- 2 Kings 16:9 KJV

- Pritchard 1969, p. 284.

- 2 Kings 15:30 KJV

Sources

- Cohn, Robert L. (2000). Cotter, David W.; Walsh, Jerome T.; Franke, Chris (eds.). 2 Kings. Berit Olam (The Everlasting Covenant): Studies In Hebrew Narrative And Poetry. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814650547.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, John J. (2014). "Chapter 14: 1 Kings 12 – 2 Kings 25". Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fortress Press. pp. 277–296. ISBN 9781451469233.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288810.

- Dietrich, Walter (2007). "13. 1 and 2 Kings". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 232–615. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Fretheim, Terence E (1997). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25565-7.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Leithart, Peter J. (2006). 1 & 2 Kings. Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1587431258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McFall, Leslie (1991), "Translation Guide to the Chronological Data in Kings and Chronicles" (PDF), Bibliotheca Sacra, 148: 3–45, archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2010CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKane, William (1993). "Kings, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 409–413. ISBN 978-0195046458.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nelson, Richard Donald (1987). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

- Pritchard, James B (1969). Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament (3 ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691035031.

- Sweeney, Marvin (2007). I & II Kings: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

External links

- Jewish translations:

- Melachim II - II Kings - Chapter 16 (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- 2 Kings chapter 16. Bible Gateway