2018 VG18

2018 VG18 is a distant trans-Neptunian object that was discovered well beyond 100 AU (15 billion km) from the Sun.[8] It was first observed on 10 November 2018 by astronomers Scott Sheppard, David Tholen, and Chad Trujillo during a search for distant trans-Neptunian objects whose orbits may be gravitationally influenced by hypothetical Planet Nine. They announced their discovery on 17 December 2018 and nicknamed the object "Farout" to emphasize its distance from the Sun.[3]

| Discovery [1][2] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | S. S. Sheppard D. Tholen C. Trujillo |

| Discovery site | Mauna Kea Obs. |

| Discovery date | 10 November 2018 (first imaged) |

| Designations | |

| 2018 VG18 | |

| "Farout" (nickname)[3] | |

| SDO [4] · TNO [5] distant [2] | |

| Orbital characteristics [5] | |

| Epoch 22 July 2019 (JD 2458686.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 8[5] · 7[2] | |

| Observation arc | 3.00 yr (1,095 days) |

| Earliest precovery date | 16 January 2017 |

| Aphelion | 123.822±0.820 AU |

| Perihelion | 37.806±0.135 AU |

| 80.814±0.535 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.53218±0.00469 |

| 726.50±7.22 yr | |

| 168.711°±18.902° | |

| 0° 0m 4.884s / day | |

| Inclination | 24.455°±0.024° |

| 245.382°±0.009° | |

| 12.722°±6.815° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean diameter | 656 km (est. at 0.12)[6] 500 km (est.)[3] |

| 24.6[7] | |

| 3.730±0.536[5] 3.5[2] · 3.9 (est.)[6] | |

As of 2020 the object is at an observed distance of 123.5 AU (18 billion km) from the Sun, which is more than three times the observed distance of the dwarf planet Pluto from the Sun. 2018 VG18 was the most distant natural object ever observed in the Solar System, until it was itself supplanted by an object initially estimated at 140 AU (21 billion km) nicknamed "FarFarOut".[9] However, 2018 VG18 is not close to being the object with the most distant orbit on average, as its semi-major axis is estimated to be only about 81 AU; in comparison, the semi-major axis of the planetoid 90377 Sedna is about 480 AU.[10]

2018 VG18 is considered to be a dwarf planet candidate, as its absolute magnitude implies that it is around 500 km (310 mi) in diameter. Assuming that the object is predominantly icy in composition, it is expected to be large enough to attain a gravitationally rounded shape, and thus be a dwarf planet.[6] Observations of 2018 VG18 show that it is pinkish in color, which indicates that it has an ice-rich surface.

Discovery

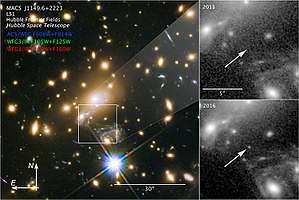

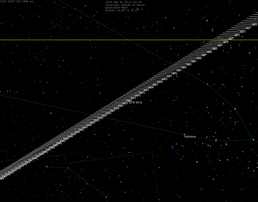

2018 VG18 was discovered by astronomers Scott Sheppard, David Tholen, and Chad Trujillo at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii on 10 November 2018.[1][3] The discovery formed part of their search for distant trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) with orbits that may be gravitationally perturbed by the hypothesized Planet Nine. The search team had been involved in the discoveries of several other distant TNOs, including the sednoids 2012 VP113 and 2015 TG387.[3][11] 2018 VG18 was first identified as a faint object slowly moving in two images taken with the 8.2-meter Subaru Telescope on the night of 10 November 2018.[1][3] At the time of discovery, 2018 VG18 was located in the constellation Taurus,[lower-alpha 1] at a very faint apparent magnitude of 24.6, approaching the lowest detectable magnitude limit for most telescopes.[1][8]

The very slow movement and low apparent magnitude of 2018 VG18 indicated that it is very distant, which prompted additional follow-up observations to constrain its orbit and distance.[3] The object was reobserved in December 2018 with the 6.5-meter Magellan-Baade telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, with observation times spanning ten days.[1] However, due to 2018 VG18's slow motion, its orbit could not be accurately calculated from the short observation arc.[11] Despite this, the discovery of 2018 VG18 along with a preliminary orbit solution was formally announced in a Minor Planet Electronic Circular issued by the Minor Planet Center on 17 December 2018.[1]

Since the announcement of 2018 VG18's discovery, the object has been occasionally observed by Scott Sheppard using the Magellan and Subaru telescopes in January, February, March, and November 2019[12][9] and also by the Gran Telescopio Canarias located at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on the island of La Palma in November 2019 and January 2020. These observations helped reduce uncertainties in 2018 VG18's orbit.[12] As of 2020, 2018 VG18 has been observed for over three oppositions, with an observation arc of 3 years (1,095 days). Only two precovery images of 2018 VG18 have been identified, and both were taken by the Cerro Tololo Observatory's Dark Energy Camera on 16 January 2017.[2]

Nomenclature

Upon the announcement of 2018 VG18's discovery, the discovers nicknamed the object "Farout" for its distant location from the Sun, and particularly because it was the farthest known TNO observed at the time.[3] On the same day, the object was formally given the provisional designation 2018 VG18 by the Minor Planet Center.[1] The provisional designation indicates the object's discovery date, with the first letter representing the first half of November and the succeeding letter and numbers indicating that it is the 457th object discovered during that half-month.[lower-alpha 2] The object has not yet been assigned an official minor planet number by the Minor Planet Center due to its short observation arc and orbital uncertainty.[2] 2018 VG18 is expected to receive a minor planet number once it has been observed for over at least four oppositions, which would take several years.[13][3] Once it receives a minor planet number, the object will be eligible for naming by its discoverers.[13]

Orbit and classification

2018 VG18 is the second-most distant observed Solar System object and is the first TNO discovered while beyond 100 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, overtaking the dwarf planet Eris (96 AU) in distance.[9][3] As of 2020 2018 VG18's distance from the Sun is 123.5 AU (18.5 billion km; 11.5 billion mi),[7] more than three times the observed distance of Pluto from the Sun (34 AU during 2018).[3] For comparison, the distances of the Pioneer 10 and Voyager 2 space probes were approximately 126 AU and 124 AU in 2020, respectively.[14] At such distances, 2018 VG18 is thought to be close to the heliopause, the boundary where the Sun's solar wind is stopped by the interstellar medium at around 120 AU.[11] The new orbit determination indicates that this object is currently very close to or at aphelion, and that it is a member of the scattered disc.

At the time of discovery on 10 November 2018, 2018 VG18's distance from the Sun was 123.4 AU, and has since moved 0.1 AU from the Sun as of May 2020.[7] As it is approaching aphelion, 2018 VG18 is receding from the Sun at a rate of 0.03 AU per year, or 0.14 kilometers per second (310 mph).[7] 2018 VG18 was the farthest TNO known until February 2019, when another distant object dubbed "FarFarOut" was discovered at about 140 AU by the same discovery team.[9] While 2018 VG18 and "FarFarOut" are among the farthest Solar System objects observable,[9] some near-parabolic comets are much further from the Sun. For example, Caesar's Comet (C/-43 K1) is over 800 AU from the Sun while Comet Donati (C/1858 L1) is over 145 AU from the Sun as of 2020.[15][16]

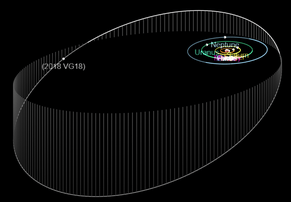

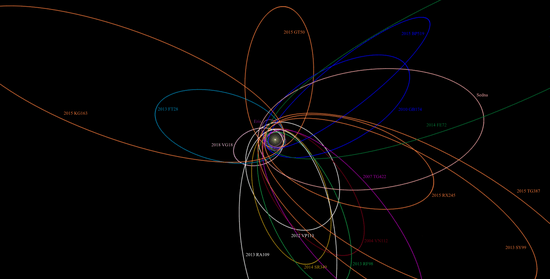

On average, 2018 VG18 orbits about 81 AU from the Sun, taking approximately 727 years to complete one full orbit around the Sun. With an orbital eccentricity of about 0.53, it follows a highly elongated orbit, varying in distance from 37.8 AU at perihelion to 123.8 AU at aphelion. Its orbit is inclined to the ecliptic plane by 24.5 degrees, with its aphelion oriented below the ecliptic.[5][2] At perihelion, 2018 VG18 approaches close to Neptune's orbit without crossing it, having a minimum orbit intersection distance of approximately 8 AU.[2] Because 2018 VG18 approaches Neptune at close proximity, its orbit has likely been perturbed and scattered by Neptune, thus it falls into the category of scattered-disc objects.[4][11] 2018 VG18 last passed perihelion in the late 17th century.[5]

Despite being one of the most distant TNOs known, 2018 VG18 does not have the largest average orbital distance (semi-major axis) among all known objects.[4] In comparison, the semi-major axis of the planetoid 90377 Sedna is about 480 AU.[10] In an extreme case, the scattered-disc object 2014 FE72 has a semi-major axis around 1,500–1,600 AU,[17] though its distance from the Sun is only 63.5 AU as of 2020, which is approximately half 2018 VG18's current distance from the Sun.[18]

Prior to orbital refinements in 2019–2020,[12] 2018 VG18 was thought to have a smaller orbit and perihelion distance, based on a preliminary orbit calculated from a short span of observations.[1] The preliminary orbit solution implied that 2018 VG18 crosses Neptune's orbit, which would have fit under the description of the centaur classification.[11] Regardless, the Minor Planet Center generally classifies 2018 VG18 as a distant object since it orbits the Sun in the outer Solar System.[2]

2018 VG18 was discovered in a particular region of the sky where other extreme TNOs have been found, suggesting that its orbit may be similar to those of extreme TNOs, which characteristically have distant and highly elongated orbits that may have resulted from the gravitational influence of the hypothetical Planet Nine.[3] 2018 VG18's nominal orbit appears to be anti-aligned with Sedna; the longitude of pericenter of 2018 VG18's orbit is oriented about 198 degrees from Sedna's orbit.[lower-alpha 3]

Physical characteristics

The size of 2018 VG18 is uncertain, though it is likely large enough to be a possible dwarf planet, based on its intrinsic brightness or absolute magnitude.[3] Based on its apparent brightness and large distance, the JPL Small-Body Database calculates 2018 VG18's absolute magnitude to be about 3.7, though this estimate has a large uncertainty.[5] The Minor Planet Center calculates 2018 VG18's absolute magnitude to be 3.5, in close agreement with the former estimate.[2] Based on the Minor Planet Center's estimate of 2018 VG18's absolute magnitude, it is listed among the top six intrinsically brightest scattered-disc objects.[4]

The albedo (reflectivity) of 2018 VG18 has not been measured nor constrained, thus its diameter could not be calculated with certainty. Assuming that the albedo of 2018 VG18 is within the range of 0.10–0.25, its diameter should be around 500–850 km (310–530 mi).[19] This size range is considered to be large enough such that the body can collapse into a spheroidal shape, and thus be a dwarf planet.[6][20] Astronomer Michael Brown considers 2018 VG18 to be highly likely a dwarf planet, based on his size estimate of 656 km (408 mi) calculated from an albedo of 0.12 and an absolute magnitude of 3.9.[6] Unless the composition of 2018 VG18 is predominantly rocky, Brown considers it very likely that 2018 VG18 has attained a spheroidal shape through self-gravity.[6] Astronomer Gonzalo Tancredi estimates that the minimum diameters for a body to undergo hydrostatic equilibrium are around 450 km (280 mi) and 800 km (500 mi), for predominantly icy and rocky compositions, respectively.[20] If the composition of 2018 VG18 is similar to the former case, the object would be considered a dwarf planet under Tancredi's criterion.

Observations of 2018 VG18 with the Magellan-Baade telescope show that the object is pinkish in color.[3] The pinkish color of 2018 VG18 is generally attributed to the presence of ice on its surface, since other ice-rich TNOs display a similar color.[3][11] Apart from its color, the spectrum and surface composition of 2018 VG18 have not yet been measured in detail and will require further observations.[11]

See also

- List of most distant trans-Neptunian objects

- List of Solar System objects by greatest aphelion

- List of Solar System objects most distant from the Sun in 2018

- List of trans-Neptunian objects

Notes

- The celestial coordinates of 2018 VG18 at the time of discovery are 04h 49m 36.353s +18° 53′ 10.69″.[1] See Taurus for constellation coordinates.

- In the convention for minor planet provisional designations, the first letter represents the half-month of the year of discovery while the second letter and numbers indicate the order of discovery within that half-month. In the case for 2018 VG18, the first letter 'V' corresponds to the first half-month of November 2018 while the succeeding letter 'G' indicates that it is the 7th object discovered on the 19th cycle of discoveries. Each completed cycle consists of 25 letters representing discoveries, hence 7 + (18 completed cycles × 25 letters) = 457.[13]

- The longitude of pericenter is the sum of the argument of pericenter (ω) and the longitude of ascending node (Ω) of the orbit of a body. For 2018 VG18's orbit, ω=12.722° and Ω=245.382°,[5] thus 12.722° + 245.382° = 258.104°. For Sedna's orbit, ω=311.532° and Ω=144.327°,[10] thus 311.532° + 144.327° = 455.859° or 95.859°. The difference between Sedna's and 2018 VG18's longitude of perihelion is about 198°, since 455.859° – 295.004° = 197.755°.

References

- "MPEC 2018-Y14 : 2018 VG18". Minor Planet Electronic Circular. Minor Planet Center. 17 December 2018. Bibcode:2018MPEC....Y...14S. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "2018 VG18". Minor Planet Center. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- "Discovered: The Most-Distant Solar System Object Ever Observed". Carnegie Science. 17 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects". Minor Planet Center. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2018 VG18)" (2019-11-30 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- Brown, Michael E. (13 September 2019). "How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system?". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Horizon Online Ephemeris System for 2018 VG18" (Settings: Sun (body center) [500@10]; Start=2018-11-10, Stop=2020-12-31, Step=1 d). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Chang, Kenneth (17 December 2018). "It's the Solar System's Most Distant Object. Astronomers Named It Farout". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- Voosen, Paul (21 February 2019). "Astronomers discover solar system's most distant object, nicknamed 'FarFarOut'". Science Magazine. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 90377 Sedna (2003 VB12)" (2018-12-07 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Plait, Phil (18 December 2018). "Meet your very, *very* distant Solar System neighbor 2018 VG18". Bad Astronomy. Syfy Wire. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "MPEC 2020-A128 : 2018 VG18". Minor Planet Electronic Circular. Minor Planet Center. 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "How Are Minor Planets Named?". Minor Planet Center. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Peat, Chris. "Spacecraft escaping the Solar System". Heavens Above. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Horizon Online Ephemeris System for -43K1". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris for Comet C/1858 L1 (Donati)". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2014 FE72)" (2018-05-15 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "AstDyS-2, Asteroids - Dynamic Site". Asteroids Dynamic Site. Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

Objects with distance from Sun over 63 AU

- Bruton, D. "Conversion of Absolute Magnitude to Diameter for Minor Planets". Department of Physics, Engineering, and Astronomy. Stephen F. Austin State University. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- Tancredi, G.; Favre, S. (2008). "Which are the dwarfs in the solar system?" (PDF). Asteroids, Comets, Meteors. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2018 VG18. |

- Discovered: The Most-Distant Solar System Object Ever Observed – Carnegie Science press release

- Farout Images – Discovery images of 2018 VG18 taken with the Subaru Telescope

- It’s the Solar System's Most Distant Object. Astronomers Named It Farout. – The New York Times article by Kenneth Chang

- Meet your very, *very* distant solar system neighbor 2018 VG18 – Bad Astronomy blog by Phil Plait

- List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects – Minor Planet Center

- 2018 VG18 at the JPL Small-Body Database