1993 Atlantic hurricane season

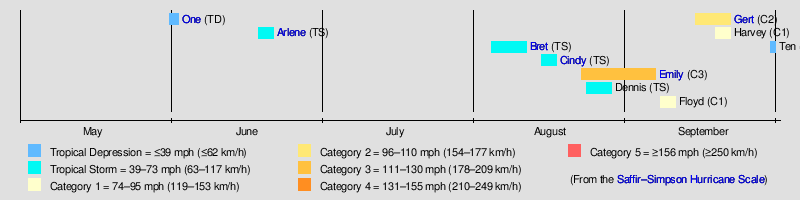

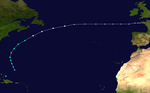

The 1993 Atlantic hurricane season was a below average Atlantic hurricane season that produced ten tropical cyclones, eight tropical storms, four hurricanes, and one major hurricane. It officially started on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates which conventionally delimit the period during which most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic Ocean. The first tropical cyclone, Tropical Depression One, developed on May 31, while the final storm, Tropical Depression Ten, dissipated on September 30, well before the average dissipation date of a season's last tropical cyclone; this represented the earliest end to the hurricane season in ten years. The most intense hurricane, Emily, was a Category 3 on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale that paralleled close to the North Carolina coastline causing minor damage and a few deaths before moving out to sea.

| 1993 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 31, 1993 |

| Last system dissipated | September 30, 1993 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Emily |

| • Maximum winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 960 mbar (hPa; 28.35 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 10 |

| Total storms | 8 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 382 total |

| Total damage | > $322.3 million (1993 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The most significant named storm of the season was Hurricane Gert, a tropical cyclone that devastated several countries in Central America and Mexico. Throughout the impact areas, damage totaled to $170 million (1993 USD)[nb 1] and 102 fatalities were reported. The remnants of Gert reached the Pacific Ocean and was classified as Tropical Depression Fourteen-E. Another significant system was Tropical Storm Bret, which resulted in 184 deaths and $25 million in losses as it tracked generally westward across Trinidad, Venezuela, Colombia, and Nicaragua. In the Pacific Ocean, the remnants of Bret were attributed to the development of Hurricane Greg. Three other tropical cyclones brought minor to moderate effects on land; they were Tropical Depression One and Tropical Storms Arlene and Cindy. The storms of the 1993 Atlantic hurricane season collectively caused 339 fatalities and $319 million in losses.

Season summary

Pre-season forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms | Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSU | December 1992 | 11 | 6 | 3 | [1] |

| CSU | April 16 | 11 | 6 | 3 | [2] |

| WRC | Early 1993 | 7 | 5 | N/A | [3] |

| CSU | June | 11 | 7 | 3 | [1] |

| CSU | August | 11 | 6 | 3 | [1] |

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 8 | ||

| Record low activity | 1 | 0 (tie) | 0 | ||

| Actual activity | 8 | 4 | 1 | ||

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by Dr. William M. Gray and his associates at Colorado State University (CSU) and the Weather Research Center (WRC). A normal season as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has 12.1 named storms, of which 6.4 reach hurricane strength, and 2.7 become major hurricanes.[nb 2][5] In December 1992, Gray anticipated a near average season with 11 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[1] Another predication on April 16, 1993 was unchanged from the previous forecast.[2] In June, Gray revised the number of hurricanes to seven, though the forecast of named storms and major hurricanes remained the same.[1] By August, the number hurricanes predicted was lowered back to six, matching the December 1992 and April forecasts.[1][2] The sole prediction made by the WRC called for seven named storms and five hurricanes, though no forecast was made on the numbers of major hurricanes.[3]

Season activity

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1, those activity began a day early with the development of Tropical Depression One on May 31.[6] It was a below average season in which 10 tropical depressions formed. Eight of the depressions attained tropical storm status, and four of these attained hurricane status. In addition, one tropical cyclone eventually attained major hurricane status, which is below the 1981–2010 average of 2.7 per season.[5] The low amount of activity is attributed to abnormally strong wind shear across the Atlantic basin.[7] Only one hurricanes and three tropical storm made landfall during the season; Tropical Depression One and Hurricane Emily also caused land impacts. However, the storm collectively caused 339 deaths and $302.7 million in damage.[8] The last storm of the season, Tropical Depression Ten, became extratropical on September 30, two months before the official end of the season on November 30.[6][9]

Tropical cyclogenesis in the 1993 Atlantic hurricane season began with the development of Tropical Depression One on May 31.[6] However, in the following two months, minimal activity occurred, with only one named storm, Arlene, in June. August was the most active month, with four tropical cyclones developing, including Tropical Storms Bret, Cindy, and Dennis, as well as Hurricane Emily.[7] Although September is the climatological peak of hurricane season,[10] only two system formed that month, which were Hurricane Floyd and Gert. Thereafter, activity briefly halted until Hurricane Harvey developed in October.[7] The final tropical cyclone, Tropical Depression Ten, became extratropical on September 30, two months before the official end of the season on November 30.[6][9]

Overall, the season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 39.[11] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. ACE is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 34 knots (39 mph, 63 km/h) or tropical storm strength. Subtropical cyclones are excluded from the total.[12]

Systems

Tropical Depression One

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 31 – June 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 999 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression One near the Isle of Youth on May 31. Due to strong wind shear and its proximity to land, the depression was unable to strengthen and struck western Cuba later that day. It emerged into the Straits of Florida early on June 1 and began to organize and intensify slightly further, but nonetheless remained below tropical storm intensity. Around that time, an approaching shortwave trough accelerated the depression northeastward across the western Bahamas. Thereafter, the wind field of the depression began expanding and lost all tropical characteristics while located northeast of The Bahamas on June 2.[13]

Heavy rainfall in Cuba caused flooding in the central and eastern portions of the country,[13] forcing the evacuation of 40,000 people, destroying 1,860 homes and damaging an additional 16,500. Additionally, crops suffered severe impact from the flooding, just two months after significant agricultural damage in Cuba from the Storm of the Century in March.[14] Overall, the depression left seven fatalities and another five people were listed as missing.[15] In Haiti, flooding from the outer bands of the storm killed thousands of livestock and resulted in 13 deaths.[16] Heavy precipitation in Florida peaked at nearly 10 in (250 mm), though it caused little impact other than bringing drought relief.[17] Impact, if any in The Bahamas, is unknown.[13]

Tropical Storm Arlene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 18 – June 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

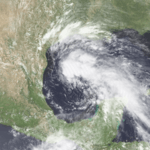

A tropical wave was tracked in the Caribbean Sea beginning on June 9 and subsequently moved across Central America. Eventually, the system entered the Gulf of Mexico, though further development was interrupted by unfavorable wind shear. After conditions became somewhat more favorable, the wave developed into Tropical Depression Two on June 18. The depression slowly strengthened as it tracked west-northwestward and eventually north-northwestward across the western Gulf of Mexico.[18] By June 19, the depression became Tropical Storm Arlene. At 09:00 UTC on the following day, Arlene made landfall on Padre Island, Texas with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). The storm quickly weakened inland and degenerated into a remnant low pressure area on June 21.[19]

In El Salvador, rainfall from the precursor tropical wave caused mudslides throughout the country, which in turn resulted in 20 fatalities. Immense amounts of precipitation in Mexico caused flooding in the states of Veracruz, Campeche, Yucatán, San Luis Potosí, Quintana Roo, Nuevo León, and Jalisco. Five deaths and $33 million in damage was reported in Mexico.[20][21] Arlene also dropped torrential rainfall in Texas, peaking at 15.26 in (388 mm) Angleton,[22] while precipitation amounts elsewhere was mainly between 9 and 11 in (230 and 280 mm). Throughout the state, numerous roads were inundated and more than 650 houses, including 25 mobile homes, suffered water damage.[23] Agriculture losses in eastern Texas include 20% of cantaloupe, 10% of watermelon, and 18% of tomatoes.[24] One fatality occurred and damage in Texas reached $22 million. Overall, Tropical Storm Arlene caused 26 deaths and $55 million in losses.[20]

Tropical Storm Bret

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 4 – August 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

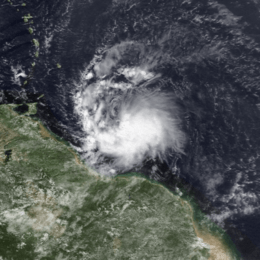

A westward-moving tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Three while located about 1,150 miles (1,850 km) west of Cape Verde on August 4. The depression strengthened and was upgraded to Tropical Storm Bret on the following day. It strengthened slightly and reached winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and maintained that intensity until crossing Trinidad on August 7. Later that day, Bret made landfall near Macuro, Venezuela, before briefly re-emerging into the Caribbean Sea. Bret made another landfall in Venezuela on August 8 and crossed northern Colombia.[25] It weakened over the mountainous terrain and fell to tropical depression intensity over the southwestern Caribbean Sea. Bret re-strengthened to a 45 mph (75 km/h) tropical storm before making landfall in southern Nicaragua on August 10. It crossed into the Pacific Ocean and dissipated, although it later regenerated into Hurricane Greg.[26]

In Trinidad, winds left 35,000 people without electricity,[27] while rainfall caused minor damage to crops and roads, with losses totaling to about $909,000.[28] Rainfall in Venezuela reached 13.3 in (340 mm) in some areas. As a result, widespread mudslides were reported, which in turn destroyed 10,000 houses and caused 173 deaths. One fatality was reported in neighboring Colombia.[7] In Nicaragua, the storm destroyed 850 houses and damaged an additional 1,500.[29] Overall, 35,000 people were left homeless in that country.[7] In addition, the destruction of 25 medical centers, 10 schools, and 10 churches occurred. Road infrastructure damage was also reported, with 12 bridges collapsing during the passage of Bret.[29] There were 10 fatalities in Nicaragua, 9 of which were drowning victims after a Spanish vessel sank. Overall, Tropical Storm Bret caused 184 deaths and about $25 million in damage.[7]

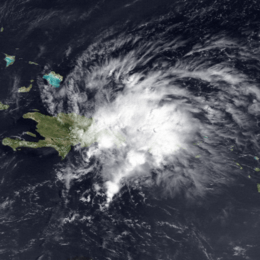

Tropical Storm Cindy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 14 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave entered the Atlantic Ocean from northwest Africa on August 8. It traversed the Atlantic and organized into Tropical Depression Four on August 14, while located within 100 mi (160 km) to the north of Barbados. After six hours, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Cindy, while crossing the island of Martinique. Due to a poor upper-level structure, Cindy barely intensified as it tracked west-northwestward across the eastern Caribbean Sea. Nonetheless, the storm peaked with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) on August 16. However, interaction with the terrain of Hispaniola caused Cindy to weaken. Late on August 16, the storm had been reduced to a tropical depression, around the time of landfall near Barahona, Dominican Republic. Cindy rapidly weakened inland and dissipated by early on August 17.[30][31]

The storm dropped torrential rainfall in Martinique, peaking at 15.55 in (395 mm) in Saint-Joseph, which fell in only two hours. Further, 2.75 in (70 mm) fell in just six minutes.[32] Several rivers overflowed as a result,[33] which in turn caused widespread flooding and mudslides.[34][35] Several roads were washed out, numerous cars were swept away, and at least 150 houses were destroyed,[34][36] leaving about 3,000 people homeless.[36][37] Overall, the storm caused two fatalities, 11 injuries, and ₣107 million (US$19 million) in damage.[31][34][38] On other Lesser Antilles, the storm caused minimally impact, limited to mostly small amounts of precipitation, light winds, and minor beach erosion, especially on Puerto Rico.[39] In Dominican Republic, street and minor river flooding was reported, which affected hundreds of residents. In addition, Cindy left two deaths in the Dominican Republic.[31][40]

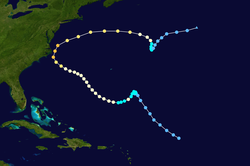

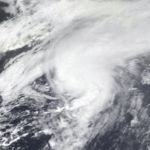

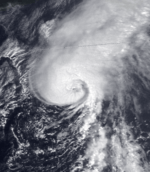

Hurricane Emily

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 22 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 960 mbar (hPa) |

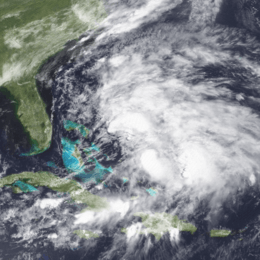

A tropical wave passed through Cape Verde on August 17. The system moved northwestward and slowly acquired a low-level center of circulation. At 18:00 UTC on August 22, Tropical Depression Five developed while located several hundred miles east-northeast of the Lesser Antilles on August 22. Initially, it headed northwestward while minimal intensification, though by August 25, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Emily. The storm then became nearly stationary while southeast of Bermuda and steadily strengthened during that time. Late on August 26, Emily briefly became a hurricane, though it weakened back to a tropical storm early on the following day. However, by late on August 27, Emily was a hurricane once again. The storm then moved northwestward and maintained Category 1 intensity until becoming a Category 2 hurricane on August 31. By 18:00 UTC, Emily became a Category 3 hurricane while just offshore Cape Hatteras.[41]

However, the storm veered out to sea later on August 29 and weakened, falling to tropical storm intensity while located northeast of Bermuda on September 3. After curving southward and then back to the northeast, Emily weakened to a tropical depression on September 4. The storm lost all tropical characteristics on September 6, while located several hundred miles southeast of Newfoundland.[42] The outer bands of Emily lashed the Outer Banks of North Carolina with heavy rainfall, high tides, and strong winds.[42] The combination of those effects damaged 553 homes beyond repair.[7] Sinkholes formed along North Carolina Highway 12 and strong winds uprooted trees, downed power lines, and tore off roofs.[43] Further north, two fishermen near Nags Head drowned, while a 15-year-old boy also drowned. Light rainfall was also reported in Maryland and Delaware.[43][44] Losses reached $45 million, with all damage in North Carolina.[44][45]

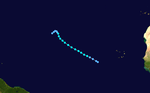

Tropical Storm Dennis

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

.jpg)  | |

| Duration | August 23 – August 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave and its associated low pressure area emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on August 21. By the following day, two METEOSAT satellites indicated that the system had a distinct cyclonic rotation and increasing deep convection. At 12:00 UTC on August 23, Tropical Depression Six developed while located about 415 mi (670 km) west-southwest of Brava, Cape Verde. Initially, a weak deep-layer mean flow caused the depression to track west-northwest. It is estimated that by 12:00 UTC on August 24, the depression became Tropical Storm Dennis, based on satellite imagery.[46]

Early on August 25, Dennis attained its peak intensity with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,000 mbar (30 inHg). After peak intensity, a relatively strong mid- to upper-level trough caused Dennis to turn north-northwestward on August 26. Thereafter, an increase in vertical wind shear and a decrease in sea surface temperatures caused the storm to begin weakening. Eventually, the low-level circulation became nearly void of deep convection. On August 27, Dennis was downgraded to a tropical depression. The storm later curved west-southwestward, while located about midway between Bermuda and the southernmost islands of Cape Verde.[46]

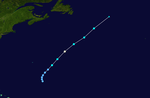

Hurricane Floyd

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 990 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave crossed the west coast of Africa on August 28. Although had it a well-defined low-level circulation, the system was not classified as a tropical cyclone. While tracking west, deep convection diminished and was nearly non-existent by August 31, though the cloud pattern began re-developing on September 3. Eventually, the system curved northwestward and remained well away from the Lesser Antilles. Because a reconnaissance flight into the system indicated a low-level circulation with persistent deep convection, it is estimated that the system became Tropical Depression Seven at 12:00 UTC on September 7, while located about 440 mi (710 km) north-northwest of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Only six hours after becoming a tropical cyclone, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Floyd. Initially, strong southwesterly wind shear prevented further significant intensification.[47]

The storm accelerated north-northwestward after becoming embedded within fast air currents, which was as Floyd moved between a strong trough and a subtropical high pressure area. Later on September 8, the storm passed about 230 mi (370 km) west of Bermuda.[47] By early on September 9, convection developed along the once exposed low-level circulation. After a buoy reported a two-minute sustained wind speed of 69 mph (111 km/h) and an eye appeared on satellite imagery, Floyd was upgraded to a hurricane at 18:00 UTC on September 9. While accelerating at nearly 52 mph (84 km/h), the storm began losing tropical characteristics as a result of colder sea surface temperatures and became extratropical at 18:00 UTC on September 10. The remnants of Floyd continued rapidly eastward and struck Brittany, France, at an intensity equivalent to a Category 1 hurricane.[48] While passing southeast of Newfoundland, the storm produced light rainfall, peaking at about 0.86 in (22 mm).[49]

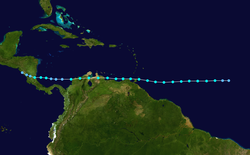

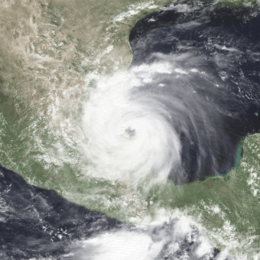

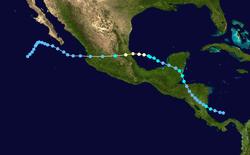

Hurricane Gert

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 14 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 970 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa on September 5. The system slowly organize while tracking across the Atlantic Ocean and much of the Caribbean Sea. It developed into a tropical depression while located north of Panama on September 14. On the following day, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Gert before moving ashore in Nicaragua. After weakening to a tropical depression, it proceeded into Honduras[50] and reorganized into a tropical storm over the Gulf of Honduras on September 17. Gert made landfall in Belize on the following day and again weakened to a depression while inland. After crossing the Yucatán Peninsula, Gert emerged over warm water in the Bay of Campeche, and strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane on September 20. The hurricane then made landfall on the Gulf Coast of Mexico near Tuxpan, Veracruz, with winds of 100 mph (165 km/h). Rugged terrain quickly disrupted its structure and Gert entered the Pacific Ocean as a tropical depression from Nayarit on September 21. Five days later, the depression dissipated near Baja California.[51]

Because Gert had a broad wind circulation, it produced widespread and heavy rainfall across Central America, which, combined with saturated soil from Tropical Storm Bret a month earlier, caused significant flooding of property and crops. Although hurricane-force winds occurred upon landfall in Mexico, the worst effects in the country were due to flooding and mudslides induced by torrential rain.[52] Following the overflow of several rivers,[53][54][55] deep flood waters submerged extensive parts of Veracruz and Tamaulipas and forced hundreds of thousands to evacuate, including 200,000 in the Tampico area alone.[56] The heaviest rainfall occurred further inland over the mountainous region of San Luis Potosí, where as much as 31.41 in (798 mm) of precipitation were measured.[57] In the wake of the disaster, the road networks across the affected countries were severely disrupted and thousands of people became homeless.[56] Extensive, but less severe flooding occurred in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. Throughout the effected areas, flooding damaged or destroyed more than 40,000 buildings.[52][56][58][59][60] The storm caused at least 102 fatalities and more than $170 million in damage.[61]

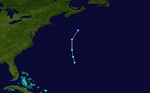

Hurricane Harvey

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 18 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 990 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave passed south of Cape Verde on September 12. By the following day, satellite imagery indicated a cloud system center. The system tracked northwestward across the Atlantic Ocean with slow further development. Due to interaction with an upper-level low on September 18, the system began to significantly organize. After a ship known as ELFS reported winds of 43 mph (69 km/h), it is estimated that Tropical Depression Nine developed at 18:00 UTC on September 18, while located about 400 miles (640 km) south-southeast of Bermuda. The depression initially moved north-northwest, though an approaching short-wave trough eventually caused it to northeastward.[62]

Convection remained disorganized and the low-level circulation was exposed on September 19. However, by the following day, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Harvey. Thereafter, the storm began to rapidly intensify and developed an eye appeared on satellite imagery. While accelerating northeastward, Harvey was upgraded to a hurricane at 18:00 UTC on September 20. However, decreasing sea surface temperatures caused Harvey to immediately weaken back to a tropical storm, while also losing tropical characteristics. At 18:00 UTC on September 21, Harvey transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while located well east of Newfoundland. Six hours later, the extratropical remnants of Harvey were absorbed into a frontal band.[62]

Tropical Depression Ten

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 29 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression Ten developed about 185 mi (300 km) southeast of Bermuda at 18:00 UTC on September 29.[9] Initially, convection associated with the depression was confined to north and east of the center.[63] The depression was difficult to track, though wind observations in Bermuda suggested that it passed just north of the island between 0300 and 07:00 UTC on September 30. Although no intensification was predicted, the National Hurricane Center noted that interaction with the approaching cold front could result in baroclinic strengthening.[64] The depression did not organize further and merged with the cold front at 00:00 UTC on October 1.[9]

Storm names

Below is a list of names used for systems that reached at least tropical storm intensity in north Atlantic Ocean during the 1993 Atlantic hurricane season.[65] This was the same list used for the 1987 season.[66] Following the season, the World Meteorological Organization did not retire any names,[67] resulting in the entire list being re-used in the 1999 season.[68] Names that were not assigned during the 1993 Atlantic hurricane season are marked in gray.

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of the storms in the 1993 Atlantic hurricane season. It mentions all of the season's storms and their names, landfall(s), peak intensities, damages, and death totals. The damage and death totals in this list include impacts when the storm was a precursor wave or post-tropical low, and all of the damage figures are in 1993 USD.

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 31 – June 2 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 999 | Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Florida, The Bahamas | Unknown | 20 | |||

| Arlene | June 18 – June 21 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1000 | Guatemala, Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi | $60.8 million | 26 | |||

| Bret | August 4 – August 11 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1002 | Trinidad, Grenada, ABC islands, Venezuela, Colombia, Nicaragua | $37.5 million | 213 | |||

| Cindy | August 14 – August 17 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1007 | Lesser Antilles (Martinique), Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic | $19 million | 4 | |||

| Dennis | August 23 – August 28 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | none | None | None | |||

| Emily | August 22 – September 6 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 960 | North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware | $35 million | 3 | |||

| Floyd | September 7 – September 10 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 990 | Newfoundland | Unknown | None | |||

| Gert | September 14 – September 21 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 970 | Central America (Nicaragua and Belize), Mexico | $170 million | 116 | |||

| Harvey | September 18 – September 21 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 990 | none | None | None | |||

| Ten | September 29 – September 30 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1008 | none | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 10 systems | May 31 – September 30 | 115 (185) | 960 | $332 million | 382 | |||||

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

- 1993 Pacific hurricane season

- 1993 Pacific typhoon season

- 1993 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season: 1992–93, 1993–94

- Australian region cyclone season: 1992–93, 1993–94

- South Pacific cyclone season: 1992–93, 1993–94

Notes

References

- "Forecast Verifications". Colorado State University. 2011. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Expert Predicts Three Severe Hurricanes in 1993". The Tuscaloosa News. Associated Press. April 17, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Jill Hasling (May 1, 2008). "Comparison of Weather Research Center's [WRC] OCSI Atlantic Annual Seasonal Hurricane Forecasts with Colorado State Professor Bill Gray's Seasonal Forecasts" (PDF). Weather Research Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- National Hurricane Center (July 11, 2010). "Glossary of NHC Terms". Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Climate Prediction Center (August 4, 2011). "Background information: the North Atlantic hurricane season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- "Hurricane season gets under way". Williamson Daily News. Associated Press. June 1, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Richard Pasch and Edward Rappaport (March 1995). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1993" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Richard Pasch and Edward Rappaport (March 1995). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1993" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Mimi Whitefield (June 1, 1993). "Heavy Rains Drench Cuba Leaving 7 Dead". Miami Herald. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Hurricane Season". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. June 6, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Edward Rappaport (December 9, 1993). Preliminary Report Tropical Storm Arlene (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Miles Lawrence (September 30, 1993). Preliminary Report Hurricane Emily (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Chris Collins. Hurricane Emily – August 31, 1993 (Report). National Weather Service Newport/Morehead City, NC. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (September 1993). Honduras Floods Sep 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 4 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- José Osorio (1994). "Impactos de los desastres naturales en Nicaragua" (PDF). Sistema Nacional de prevencion y manejo de desastres naturales (in Spanish). Biblioteca Virtual en Salud y Desastres. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012.

- "Storm hits two nations". Sun-Sentinel. September 17, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Mario Lungo and Pohl Lina (2006). "Las acciones de prevención y mitigación de desastres en El Salvador: Un sistema en construcción" (PDF). De terremotos, derrumbes, e inundados (in Spanish). Red de Estudios Sociales en Prevención de Desastres en América Latina. p. 34. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Ana Moisa; Ernesto Romano; Louis Velis, eds. (October 12, 1993). "[Various short articles]" (PDF). Actualidades Sobre Desastres: Boletin de Extensión Cultural de CEPRODE: Centro de Protección Para Desastres (in Spanish). CEPRODE: Centro de Protección para Desastres. 1 (1). section 3 "Actividades de las comunidades", p. [8]. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (October 1, 1993). Mexico Tropical Storm Oct 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 3 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Storms near Puerto Rico and Hawaii". Houston Chronicle. August 16, 1993. section A, p. 6. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- La Martinique : entre menace marine et terre instable (Report) (in French). La Chaîne Météo. May 6, 2009. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Miles Lawrence (October 22, 1993). Preliminary Report Tropical Depression Ten (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Neal Dorst (January 21, 2010). "Subject: G1) When is hurricane season?". Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Hurricane Research Division (March 2011). "Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- David Levinson (August 20, 2008). "2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- Lixion Avila (June 30, 1993). Preliminary Report Tropical Depression One (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (DHA) (June 4, 1993). Cuba — Floods Jun 1993 UN DHA Information Report No. 1 (Report). Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Mimi Whitefield (June 1, 1993). "Heavy Rains Drench Cuba Leaving 7 Dead". Miami Herald. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Hurricane Season". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. June 6, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- David Roth (April 6, 2010). Tropical Depression One - May 30-June 1, 1993 (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Edward Rappaport (December 9, 1993). Preliminary Report Tropical Storm Arlene (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Edward Rappaport (December 9, 1993). Preliminary Report Tropical Storm Arlene (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Edward Rappaport (December 9, 1993). Preliminary Report Tropical Storm Arlene (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Lluvias dejan muertos y damnificados" (in Spanish). National Hurricane Center. 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- David Roth (May 2, 2007). "Tropical Storm Arlene - June 18-23, 1993". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Tropical Storm Arlene - June 18-23, 1993 (Report). National Weather Service Corpus Christi, Texas. Archived from the original on November 8, 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Grant Goodge. Storm Data and Unusual Phenomena with Late Reports and Corrections (PDF) (Report). National Climatic Data Center. p. 253. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Richard Pasch (November 22, 1993). Tropical Storm Bret Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Richard Pasch (November 22, 1993). Tropical Storm Bret Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Tropical storm hin its Trinidad and Tobago". Indiana Gazette. Associated Press. August 8, 1993.

- Joslyn Edwards. Disaster mitigation for hospitals and other health care facilities in Trinidad and Tobago (Report). p. 17.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarians Affairs (August 18, 1993). Nicaragua Tropical Storm Aug 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 8 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Max Mayfield (October 25, 1993). "Tropical Storm Cindy Preliminary Report". National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- Max Mayfield (October 25, 1993). "Tropical Storm Cindy Preliminary Report". National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- Saffache Pascal (2005). "Chapitre 2: Contexte de l'agriculture martiniquaise: atouts et contraintes pour l'agriculture biologique" (PDF). Agriculture biologique en Martinique [Organic agriculture in Martinique] (PDF) (in French). IRD Editions. part 2, chapter 2, para. 3, p. 49. ISBN 2-7099-1555-3.

- Saffache Pascal. "Caractéristiques typologiques et dynamiques des rivières de la Martinique" (PDF) (in French). Université des Antilles et de la Guyane: Département de Géographie-Aménagement. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 5, 2012.

- La Martinique : entre menace marine et terre instable (Report) (in French). La Chaîne Météo. May 6, 2009. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Department of Humanitarian Affairs (1995). "DHA news" (13–17). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: 43. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Storms near Puerto Rico and Hawaii". Houston Chronicle. August 16, 1993. section A, p. 6. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Storm Cindy soaks Martinique, heads for Dominican Republic". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. August 16, 1993. section A, p. 4. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- 1993 Cindy: Tempête tropicale. Pluies extrêmes aux Antilles (Report) (in French). Météo-France. n.d. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- United States Geological Survey (1993). U.S. Geological Survey DCP's rainfall from 08-15-93 0000L thru 08-16-93 2400L (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Ricardo Leon (August 16, 1993). "Tropical storm threatens Hawaii". Sun Journal. Associated Press. p. 3. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Miles Lawrence (September 30, 1993). Preliminary Report Hurricane Emily (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Miles Lawrence (September 30, 1993). Preliminary Report Hurricane Emily (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Hurricane Climbs N.C. Coast to Virginia". Washington Post. September 1, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Miles Lawrence (September 30, 1993). Preliminary Report Hurricane Emily (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Chris Collins. Hurricane Emily – August 31, 1993 (Report). National Weather Service Newport/Morehead City, NC. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Lixion Avila (October 7, 1993). Tropical Storm Dennis Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- Edward Rappaport (October 6, 1993). Hurricane Floyd Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- Edward Rappaport (October 6, 1993). Hurricane Floyd Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- "1993-Floyd". Environment Canada. September 14, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- Richard Pasch (November 10, 1993). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- Richard Pasch (November 10, 1993). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- Richard Pasch (November 10, 1993). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- "Mexico hit hard by storm". The Gazette. September 22, 1993. section B, p. 1.

- "1993 Global Register of Extreme Flood Events". Global Active Archive of Large Flood Events. Dartmouth Flood Observatory. July 2003. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Prisciliano Gutiérrez (December 1993). Las inundaciones causadas por el huracán "Gert" sus efectos en Hidalgo, San Luis Potosi, Tamaulipas y Veracruz (PDF) (in Spanish). El Sistema Nacional de Proteccion Civil. pp. 14, 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (October 1, 1993). Mexico Tropical Storm Oct 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 3 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- David Roth (January 27, 2007). Hurricane Gert/T.D. #14E - September 14-28, 1993 (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Mario Lungo and Pohl Lina (2006). "Las acciones de prevención y mitigación de desastres en El Salvador: Un sistema en construcción" (PDF). De terremotos, derrumbes, e inundados (in Spanish). Red de Estudios Sociales en Prevención de Desastres en América Latina. p. 34. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Informe final de operaciónes Tormenta Gert" (PDF). Plan regulador para la reconstrucción de las zonas afectadas por la tormenta tropical Gert (in Spanish). Comisión Nacional de Emergencias. September 25, 1993. section e, pp. 4, 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (September 17, 1993). Nicaragua Tropical Storm Aug 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 8 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (September 1993). Honduras Floods Sep 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 4 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- José Osorio (1994). "Impactos de los desastres naturales en Nicaragua" (PDF). Sistema Nacional de prevencion y manejo de desastres naturales (in Spanish). Biblioteca Virtual en Salud y Desastres. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012.

- "Storm hits two nations". Sun-Sentinel. September 17, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Mario Lungo and Pohl Lina (2006). "Las acciones de prevención y mitigación de desastres en El Salvador: Un sistema en construcción" (PDF). De terremotos, derrumbes, e inundados (in Spanish). Red de Estudios Sociales en Prevención de Desastres en América Latina. p. 34. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Ana Moisa; Ernesto Romano; Louis Velis, eds. (October 12, 1993). "[Various short articles]" (PDF). Actualidades Sobre Desastres: Boletin de Extensión Cultural de CEPRODE: Centro de Protección Para Desastres (in Spanish). CEPRODE: Centro de Protección para Desastres. 1 (1). section 3 "Actividades de las comunidades", p. [8]. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (October 1, 1993). Mexico Tropical Storm Oct 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 3 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Richard Pasch (November 10, 1993). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert: 14-21 September 1993 (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- Max Mayfield (October 19, 1993). Hurricane Harvey Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- Miles Lawrence and Bill Wright (September 30, 1993). Tropical Depression Ten Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Richard Pasch (September 30, 1993). Tropical Depression Ten Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Arlene...Bret...Cindy...Dennis...Tropical storms and..." Orlando Sentinel. August 26, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Arlene, Adrian storms' name". TimesDaily. May 25, 1987. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names". National Hurricane Center. April 13, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1996). "Atlantic Storms 1996-2001". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved October 4, 2011.