1973 Atlantic hurricane season

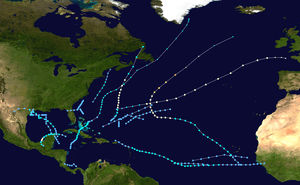

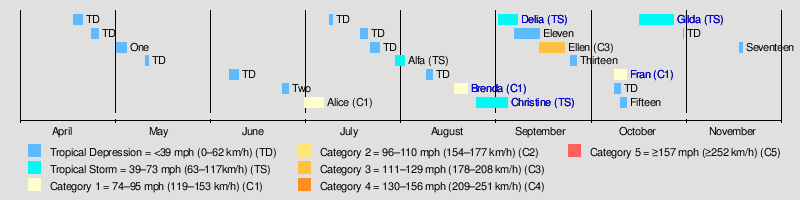

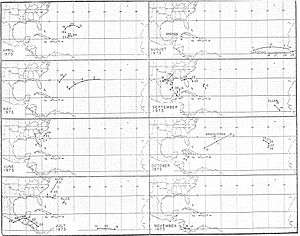

The 1973 Atlantic hurricane season was the first season to use the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale,[1] a scale developed in 1971 by Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson to rate the intensity of tropical cyclones.[2] The season produced 24 tropical and subtropical cyclones, of which only 8 reached storm intensity, 4 became hurricanes, and only 1 reached major hurricane status. Although more active than the 1972 season, 1973 brought few storms of note. Nearly half of the season's storms affected land, one of which resulted in severe damage.

| 1973 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | April 18, 1973 |

| Last system dissipated | October 27, 1973 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Ellen |

| • Maximum winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 962 mbar (hPa; 28.41 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 24 |

| Total storms | 8 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 22 total |

| Total damage | $28 million (1973 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The season officially began on June 1, 1973, and lasted until November 30, 1973. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin.[3] However, the first system formed on April 18, more than a month before the official start. Three more depressions formed before June 1; however, none attained storm intensity. The first named storm of the year was Hurricane Alice which formed on July 1 and became the first known cyclone to affect Bermuda during July. More than a month later, the second hurricane, Brenda, formed and was considered the worst storm to strike Mexico along the eastern coast of the Bay of Campeche, killing 10 people.

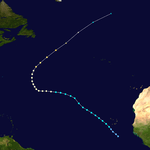

Later in August, Tropical Storm Christine became the easternmost forming tropical cyclone on record when it formed over Guinea. The most intense storm of the season was Hurricane Ellen, a Category 3 cyclone that remained over open water. The final named storm was meteorologically significant in that it became the first recorded tropical cyclone to transition into a subtropical cyclone. No names were retired during the season; however, due to the addition of male names into the list of Atlantic hurricane names in 1979, several of the names were removed and have not been used since.

Season summary

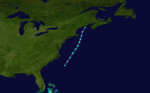

The first storm of the 1973 hurricane season, forming in mid-April, developed more than a month before the official start of the season. Several other short-lived, weak depressions formed before and during June; however, none reached storm intensity. The first named storm, Alice, formed on July 1. Tracking generally to the north, Alice also became the first hurricane of the season as well as the first known cyclone to impact Bermuda during July. Shortly after Alice dissipated over Atlantic Canada, another depression formed. By the end of July, two more non-developing depressions formed and the first subtropical cyclone, given the name Alfa, developed off the east coast of the United States. This storm was short-lived and dissipated on August 2 just offshore southern Maine. The first half August was relatively quiet, with only one depression forming. However, later in the month, the season's second hurricane, Brenda, formed in the northwestern Caribbean. Peaking just below Category 2 status on the newly introduced Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale, Brenda made the first recorded landfall in the Mexican State of Campeche.[4]

Later in August, Tropical Storm Christine became the easternmost forming tropical cyclone in the Atlantic basin on record, developing over the western African country of Guinea on August 25. The system traveled for several thousand miles before dissipating in the eastern Caribbean Sea in early September. At the start of the month, a new tropical storm formed in the Gulf of Mexico. This storm, named Delia, became the first known cyclone to make landfall in the same city twice. After moving inland a second time, Delia eventually dissipated on September 7. As Delia dissipated another depression formed in the same region, eventually making landfall in the same city as Delia, Freeport, Texas. Another brief depression formed several days later. On September 13, the strongest storm of the season, Ellen, formed over the eastern Atlantic. After tracking northwest for several days, Ellen eventually attained hurricane status as it turned westward. Several days later, the hurricane turned northeast due to an approaching frontal system. Shortly before becoming extratropical, Ellen reached major hurricane intensity at a record northerly latitude.[4]

In late September, a brief depression affected northern Florida before dissipating. After a week of inactivity, the second subtropical storm of the year formed over the central Atlantic. This storm, named Bravo, gradually intensified, becoming fully tropical, at which time it was renamed Fran, a few days later. Upon being renamed, Fran had intensified into a hurricane and maintained this intensity for several days before dissipating east of the Azores on October 12. A few days after Fran dissipated, the final named storm of the year formed in the central Caribbean Sea. A slow moving system, Gilda gradually intensified just below hurricane-intensity before striking Cuba and moving over the Bahamas. A few days after passing through the islands, Gilda became the first storm on record to transition from a tropical cyclone into a subtropical cyclone. A large storm, Gilda eventually became extratropical near Atlantic Canada and dissipated later that month. Around the time Gilda was dissipating, a weak depression briefly existed near the Azores. The final storm of the year was a strong depression in the southern Caribbean Sea. This system was active for less than two days but may have briefly attained tropical storm intensity as it made landfall in southern Nicaragua.[4]

Systems

Hurricane Alice

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 1 – July 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) |

The first named storm formed out of the interaction between tropical wave and a mid-level tropospheric trough northeast of the Bahamas in late-June. A well-defined circulation became apparent by June 30 and satellite images depicted cyclonic banding features.[4] The following day, the system intensified into a tropical depression[5] and shortly thereafter became a tropical storm as reconnaissance aircraft recorded gale-force winds. An area of high pressure to the east of Alice steered the storm generally to the north. Decreasing wind shear allowed the storm to become increasingly organized and a well-defined eye developed by July 3. By this time, reconnaissance had determined that the storm had intensified into a hurricane, with maximum winds reaching 80 mph (130 km/h).[4]

On July 4, the storm reached its peak intensity with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 986 mbar (hPa; 29.11 inHg), as the eastern portion of the eyewall brushed Bermuda. After passing the island, Alice began to accelerate in response to a mid-level trough over the eastern United States and weakened. By July 6, winds head decreased below hurricane intensity as the storm neared Atlantic Canada.[4] Later that day, Alice made landfall in eastern Newfoundland with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h)[5] before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone.[4]

During its passage of Bermuda, Alice produced sustained winds up to 75 mph (120 km/h) and gusts to 87 mph (140 km/h).[4][6] No major damage was recorded on the island, though the winds blew down a few trees and powerlines.[7] The heavy rainfall,[8] peaking at 4.57 in (116 mm),[9] ended a three-month drought in Bermuda.[8] Although Alice tracked through Atlantic Canada,[4] no impact was recorded.[10]

Subtropical Storm Alfa

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 30 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

During late July, an upper-level low, with a non-tropical cold core, formed near Cape Hatteras, North Carolina and tracked southward. Gradually, the circulation lowered to the surface and developed subtropical characteristics. On July 31, the system attained gale-force winds off the Mid-Atlantic coast and was named Alfa, the first name from the list of subtropical storm names for the 1973 season. Tracking north-northeast, the system intensified very little as it paralleled the coastline. By August 1, the system weakened below subtropical storm intensity as it neared New England. The following day, Alfa dissipated just off the southern coast of Maine.[4] The only effects from Alfa was light to moderate rainfall in New England, peaking at 5.03 in (128 mm) in Turners Falls, Massachusetts. Most of southern Maine recorded around 1 in (25 mm),[11] with a maximum of 2.59 in (66 mm) in Saco.[12]

Hurricane Brenda

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 18 – August 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 977 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane Brenda originated from a tropical wave that moved off the western coast of Africa on August 9; however, the initial wave quickly weakened upon entering the Atlantic Ocean. By August 13, the wave began to regenerate as it passed through the Lesser Antilles. Several days later, convection associated with the system consolidated into a central, organized mass[4] and on August 18, the system had become sufficiently organized to be declared a tropical depression while situated near the Yucatán Channel.[5] Early the next day, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Brenda as it made landfall in the northern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula. After moving inland, a strong ridge of high pressure over Texas forced the storm to take an unusual track, eventually leading it to enter the Bay of Campeche on August 20.[4]

Once back over water, Brenda began to intensify, attaining hurricane status late on August 20. The next day, a well-defined eye had developed and the storm attained its peak intensity as a high-end Category 1 hurricane with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 977 mbar (hPa; 28.85 inHg). The storm made landfall later that day near Ciudad del Carmen, Mexico at this intensity, becoming the first hurricane on record to strike the region. After moving inland, Brenda rapidly weakened to a depression by the morning of August 22 and dissipated later that day.[4]

Already suffering from severe flooding that killed at least 18 people and left 200,000 homeless, Hurricane Brenda worsened the situation with torrential rainfall and additional flooding.[13] The storm killed at least 10 people in the country.[4] Following the damage wrought by Brenda, a large earthquake struck the region, hampering relief efforts and collapsing numerous structures.[14] Winds on land gusted up to 112 mph (180 km/h), leading to severe wind damage. Two of the fatalities occurred in Campeche after 80% of the city was flooded.[15] This was considered the worst flooding in the city in over 25 years. An estimated 2,000 people were left homeless as a direct result of Brenda throughout Mexico.[4] Offshore, a freighter with 25 crewman became trapped in the storm after its engines failed.[15] They were safely rescued several days later once the storm had dissipated.[4]

Tropical Storm Christine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 25 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 996 mbar (hPa) |

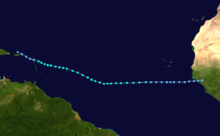

The easternmost forming Atlantic tropical cyclone on record, Tropical Storm Christine, originated as a tropical wave over Africa in mid-August. As it neared the Atlantic Ocean, the wave spawned a tropical depression at 14.0°W, over the country of Guinea, unlike most cyclone producing waves which travel several hundred miles over water before spawning a depression. Although it was already a depression, advisories on the storm were not issued until August 30, five days after its formation.[4] For several days, the depression maintained its intensity as it steadily tracked west across the Atlantic. It eventually attained tropical storm intensity on August 28.[5] Despite the lack of aircraft reconnaissance in the region, the intensity was determined by wind readings from a German cargo ship that passed through the storm.[4]

On August 30, the first reconnaissance mission into the storm found tropical storm-force winds and the first advisory was issued that day, immediately declaring the system as Tropical Storm Christine. Three days later, Christine attained its peak intensity just below hurricane-status with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 996 mbar (hPa; 29.41 inHg). Shortly thereafter, increasing wind shear caused the storm to weaken as it neared the Leeward Islands. As it passed over Antigua on September 3, Christine weakened to a tropical depression and eventually dissipated near the Dominican Republic later that day.[4]

During its passage through the Leeward Islands, Christine produced torrential rainfall, peaking at 11.74 in (298 mm) in southeastern Puerto Rico.[16] These rains led to flooding on several islands. One person was killed during the storm after being electrocuted by a downed power line on a flooded road.[4] Schools were closed ahead of the storm in Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands as a precaution following the issuance of flood warnings. Six scientists had to be evacuated from the small island of Aves once the storm posed a threat to them. No major damage was reported on any of the affected islands in the wake of Christine.[17]

Tropical Storm Delia

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) |

On August 27, a tropical wave formed over the central Caribbean and tracked towards the west-northwest. The system gradually developed organized shower and thunderstorm activity. By September 1, a tropical depression developed from the wave. By September 3, the depression had intensified into a tropical storm, receiving the name Delia, and began tracking more towards the west. A complex steering pattern began to take place later on that day, resulting in the creation of a more hostile environment for tropical cyclones in the Gulf of Mexico.[4] As Delia neared the Texas coastline, it managed to intensify into a strong tropical storm with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). The lowest pressure was recorded at 986 mbar (hPa; 29.11 inHg) at this time. Shortly thereafter, the cyclone made its first landfall in Freeport, Texas late on September 4. After executing a counterclockwise loop, the storm made landfall in Freeport again on September 5. After moving inland, the storm quickly weakened, becoming a depression on September 6 before dissipating early the next day over northern Mexico.[4]

Due to the erratic track of the storm along the Texas coastline, widespread heavy rains fell in areas near the storm and in Louisiana. Tides up to 6 ft (1.8 m), in addition to rainfall up to 13.9 in (350 mm), caused significant flooding in the Galveston-Freeport area. Up to $3 million was reported in damages to homes due to the flooding. Throughout Louisiana, there was substantial flooding of farmland. Damages to crops amounted to $3 million. In addition to the flooding rains produced by Delia, eight tornadoes also touched down due to the storm, injuring four people. Five people were killed during Delia, two drowned during floods, two died in a car accident and the other died from a heart attack while boarding up his home.[4]

Tropical Depression Eleven

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 6 – September 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) |

On September 6, a tropical depression formed over the northwestern Caribbean Sea within a trough of low pressure extended southeastward from Delia, which was situated over southeast Texas at the time. The depression remained weak until it reached the Texas coastline on September 10. Once onshore, it produced significant rainfall, causing significant damage that was attributed to Tropical Storm Delia.[4] After turning northeast and tracking inland, the depression quickly increased in forward speed before dissipating over North Carolina on September 14.[18]

Along the coasts of Texas and Louisiana, the depression produced significant amounts of rainfall, peaking at 11.15 in (283 mm) near Freeport.[18] Several areas in southern Louisiana recorded rainfall exceeding 5 in (130 mm) with a maximum amount of 9.2 in (230 mm) falling in Kinder.[19] Significant rainfall was also recorded in the Carolinas and Georgia, with numerous areas recording over 3 in (76 mm).[18] A maximum of 9.35 in (237 mm) fell near Whitmire, South Carolina before the system dissipated.[20] In all, the depression resulted in an additional $22 million in crop losses in southern Louisiana.[4][21]

Hurricane Ellen

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 14 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 962 mbar (hPa) |

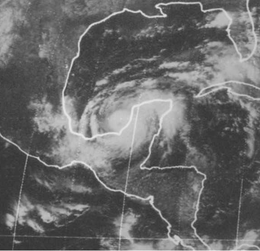

The strongest storm of the season, Hurricane Ellen, began as a tropical wave that moved off the western coast of Africa on September 13.[4] On the following day, the wave spawned an area of low pressure south of the Cape Verde Islands that quickly became a tropical depression. Tracking northeast, the system intensified into a tropical storm on September 15 after sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) were reported by a French naval vessel; however, due to sparse data on the storm, the first advisory on Ellen was not issued for two more days. A slightly elongated storm, Ellen gradually intensified over the open Atlantic and was steered by two troughs of low pressure. On September 18, the storm took a nearly due west track and the system became increasingly organized, with an ill-defined eye becoming present on satellite imagery.[4]

The next day, Ellen intensified into a hurricane before taking a sharp turn to the north-northwest in response to a weak trough moving northeast from the Bahamas. Gradually, the hurricane turned more towards the northeast and began to accelerate as well as intensify. Despite being at an unusually high latitude for development, the storm underwent a brief period of rapid intensification, strengthening into a Category 3 hurricane on September 23. At that time, Ellen attained its peak intensity with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 962 mbar (hPa; 28.41 inHg).[4] Upon attaining this intensity at 42.1°N, Ellen had become a major hurricane farther north than any other tropical cyclone on record, and is one of two storms to become a major hurricane north of 38°N, the other being Hurricane Alex in 2004.[5] Shortly after peaking, Ellen transitioned into an extratropical cyclone before merging with a frontal system several hundred miles east of Newfoundland on September 23.[4]

Hurricane Ellen was photographed by the Skylab 3 mission from orbit, from the Skylab space station.[22]

Tropical Depression Thirteen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min) 1010 mbar (hPa) |

On September 24, a depression formed northeast of the Bahamas.[23] The following day, the NHC issued their first advisory on the system, declaring it a subtropical depression. The depression was displayed an asymmetrical structure, with most winds being recorded up to 300 mi (480 km) north of the center.[24] Later that day, the subtropical depression organized into a tropical depression. Upon doing so, the NHC issued small craft advisories for coastal areas between North Carolina and St. Augustine, Florida.[25] Tracking north-northwestward in response to a break in a subtropical ridge to the north, the depression eventually made landfall near Marineland, Florida and quickly weakened, dissipating before reaching the Gulf of Mexico.[23]

Heavy rain fell in association with the depression in parts of Florida and Georgia. A maximum of 6.74 in (171 mm) fell in Orlando while several other areas recorded over 3 in (76 mm) of rain.[23] Over land, wind gusts reached 40 mph (65 km/h) in some locations.[26] Offshore, swells produced by the system reached 10 ft (3.0 m), impacting several vessels in the region.[24] Minor beach erosion and coastal flooding was reported in parts of South Carolina as a result of the storm.[27] In parts of coastal Georgia, high water resulted in several road closures and flooded a few homes. Police officers in Savannah reported that wave were topping the local seawall; however, no damage was reported.[28]

Hurricane Fran (Bravo)

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 8 – October 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 978 mbar (hPa) |

The final hurricane of the season, Fran, originated from an area of convection north of Hispaniola on October 1. By October 4, the system interacted with a mid-tropospheric trough near the southeast United States, resulting in the formation of a surface low. Tracking eastward, showers and thunderstorms began to develop around the circulation; however, the structure of the system was not fully tropical.[4] Late on October 8, the cyclone had become sufficiently organized to be classified a subtropical depression.[5] Cold air from the remnants of a cold front became entrained within the circulation; however, the cold air gradually warmed. The following day, winds increased to gale-force and the depression was upgraded to a subtropical storm, at which time it was given the name Bravo.[4]

By October 10, Bravo had intensified substantially, as hurricane hunters recorded hurricane-force winds roughly 15 mi (25 km) from the center of the storm. Following this finding, the National Hurricane Center reclassified the system as a tropical system and renamed it Fran, dropping its previous designation of Bravo.[4] Steered generally eastward by a deep surface low in the westerlies, Fran accelerated towards the Azores Islands. Shortly after bypassing the islands on October 12, the central pressure of Fran decreased to 978 mbar (hPa; 28.88 inHg), the lowest recorded in relation to the hurricane. Shortly after reaching this intensity, the hurricane transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and quickly merged with a cold front off the coast of France. Although Fran passed near the Azores, no impact was recorded on any of the islands.[4]

Tropical Storm Gilda

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 16 – October 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 984 mbar (hPa) |

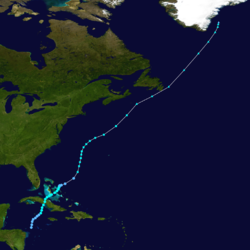

The precursor to Tropical Storm Gilda was a large convective system partially due to a tropical wave. It gradually became better organized over the northwestern Caribbean Sea, and on October 15, a tropical depression formed off the coast of Nicaragua. As it drifted to the northeast, it strengthened to a tropical storm, peaking at 70 mph (110 km/h) winds. Before it hit the coast of Cuba, it weakened enough to cause only minor damage. By the time it struck the island, it had become very disorganized in nature.[4]

On October 24, cool, dry air entered the newly developed convection, and as a result it transitioned into a subtropical cyclone. Gilda became the first tropical system to pass through a subtropical stage prior to becoming extratropical. The large circulation continued northeast before becoming extratropical on October 27. The remnants of Gilda intensified as they tracked near Atlantic Canada, attaining a central pressure of 968 mbar (hPa; 28.58 inHg) near Cape Race, Newfoundland. The system eventually dissipated near southern Greenland on October 29.[4]

Gilda caused heavy rain and mudslides in Jamaica, destroying six homes[29] and killing six people.[30] In Cuba, Gilda dropped over 6 in (150 mm) of rain, while 60 mph (95 km/h) winds were reported in the northern part of the country. In the Bahamas, Gilda caused significant crop damage from heavy rainfall and high tides. The storm's persistent strong currents and easterly winds caused moderate beach erosion on the East Coast of the United States, mostly along the Florida coast. The extratropical remnants of the storm produced hurricane-force wind gusts over parts of Atlantic Canada, peaking at 75 mph (120 km/h); however, no damage was reported.[4]

Other storms

In addition to the eight named storms of 1973 and two notable tropical depressions, there were several minor systems that were classified as depressions by the National Hurricane Center.[31] The first four systems of the year were not classified as fully tropical, rather they were associated with the remnants of decaying cold fronts. On April 18, the first of these depressions formed northeast of the Bahamas and tracked in a curved motion before dissipating over open water on April 21. Several days later, on April 24, another depression formed in the same general region; however, this system was shorter lived and dissipated two days later without significant movement. On May 2, another partially tropical system formed over open waters. The cyclone tracked northeast and dissipated late on May 5 east-southeast of the Azores. On May 11, a brief depression formed near Bermuda but dissipated the following day.[4] Roughly a week into the official hurricane season, the fifth depression of the year formed just offshore southeast Florida, near Miami. The system tracked northwest across the peninsula and briefly entered the Gulf of Mexico on June 8 before making landfall along the Florida Panhandle. The depression eventually dissipate on June 10 over South Carolina.[4]

On June 23, another depression formed along Florida, this time just onshore near the Georgia border. The system slowly tracked northeastward before dissipating on June 26 southeast of the North–South Carolina border. As Hurricane Alice neared Bermuda on July 9, a depression formed near the east coast of the United States; however, the storm dissipated the following day. On July 19, the first Cape Verde storm formed over the central Atlantic. This system did not intensify, remaining a weak depression and dissipated on July 21 without affecting land. The next day, a new depression formed over the southwestern Caribbean Sea near the coast of Nicaragua. The depression tracked over Central America, briefly moving back over water in the Gulf of Honduras before making a second landfall in Belize. The system persisted over land for a few days before entering the eastern Pacific late on July 25.[4]

Only one non-developing depression formed during the month of August, an unusually eastward forming system. The depression was first identified just offshore eastern Africa on August 8, near where Tropical Storm Christine formed later in the month. Tracking rapidly towards the west, the depression dissipated on August 11 over open waters. In addition to the two notable tropical depressions and two named storms in September, a slow-moving depression formed south-southeast of Bermuda on September 8. Tracking generally northward, the depression dissipated early on September 10 without affecting land. Upon the declaration of Hurricane Fran on October 10, a new depression formed southwest of the strengthening hurricane. This system rapidly tracked northeast and dissipated two days later. Later that month, a slow-moving depression formed near the Azores. This system tracked southeast and dissipated on October 30 without affecting land.[4] The final system of the year formed near the northern coast of Panama on November 17. The depression was noted as a "...strong depression..."[4] by the National Hurricane Center and may have briefly attained tropical storm intensity before making landfall in northern Costa Rica on November 18; the system dissipated later that day over land.[5] [4]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1973.[1] Storms were named Christine, Delia, Ellen and Fran for the first time in 1973.[5] Due to the relatively minimal impact caused by storms during the season,[4] no names were retired in the spring of 1974;[32] however, due to the addition of male names in 1979, the list was removed and replaced with a new set of names.[33] Fran, Kate, Rose, and Sally got placed onto the modern lists, with Fran being retired after 1996.

|

|

Subtropical storm names

The following names were used for subtropical storms in the Atlantic basin for this year.[4] This year was the second and last year to use the phonetic alphabet.[5] Although a storm was given the name Bravo, it was renamed Fran after acquiring tropical characteristics.[4]

|

|

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of the storms in 1973 and their landfall(s), if any. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but are still storm-related. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical or a wave or low.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Name | Dates active | Peak classification | Sustained wind speeds |

Pressure | Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 2 – May 5 | Tropical depression | 30 mph (45 km/h) | 1007 hPa (29.74 inHg) | None | None | None | [34] |

| Two | June 24 – June 26 | Tropical depression | 30 mph (45 km/h) | 1010 hPa (29.83 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| Alice | July 1 – July 7 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 mph (150 km/h) | 986 hPa (29.12 inHg) | Bermuda, Newfoundland | Minimal | None | |

| Alfa | July 30 – August 2 | Subtropical storm | 45 mph (75 km/h) | 1005 hPa (29.68 inHg) | New England | None | None | |

| Brenda | August 18 – August 22 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 mph (150 km/h) | 977 hPa (28.85 inHg) | Mexico | Unknown | 10 | |

| Christine | August 25 – September 4 | Tropical storm | 70 mph (110 km/h) | 996 hPa (29.41 inHg) | Leeward Islands | Unknown | 0 (1) | |

| Delia | September 1 – September 7 | Tropical storm | 70 mph (110 km/h) | 986 hPa (29.12 inHg) | Mexico, Texas | $6 million | 2 (3) | |

| Eleven | September 6 – September 12 | Tropical depression | 35 mph (55 km/h) | 1003 hPa (29.62 inHg) | Quintana Roo, Mexico, Texas | $22 million | None | |

| Ellen | September 14 – September 22 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 mph (185 km/h) | 962 hPa (28.41 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| Thirteen | September 24 – September 26 | Tropical depression | 30 mph (45 km/h) | 1010 hPa (29.83 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| Fran (Bravo) | October 8 – October 12 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 mph (130 km/h) | 978 hPa (28.88 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| Fifteen | October 10 – October 12 | Tropical depression | 30 mph (45 km/h) | 1004 hPa (29.65 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| Gilda | October 16 – October 27 | Tropical storm | 70 mph (110 km/h) | 984 hPa (29.06 inHg) | Cuba, Bahamas | Unknown | 6 | |

| Seventeen | November 17 – November 18 | Tropical depression | 35 mph (55 km/h) | 1008 hPa (29.77 inHg) | Costa Rica | Unknown | None | |

| Season aggregates | ||||||||

| 24 cyclones | April 18 – November 18 | 115 mph (185 km/h) | 962 hPa (28.4 inHg) | $28 million | 18 (4) | |||

See also

- Lists of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

- 1973 Pacific hurricane season

- 1973 Pacific typhoon season

- 1973 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- Southern Hemisphere tropical cyclone seasons: 1972–73, 1973–74

References

- "'73 Hurricanes to Be Graded". The Bridgport Post. Associated Press. May 9, 1973. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 19, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Jack Williams (May 17, 2005). "Hurricane scale invented to communicate storm danger". USA Today. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Neal Dorst; C. J. Neumann (1993). "Subject: G1) When is hurricane season?". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Paul J. Herbert; Neil L. Frank (January 28, 1974). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1973" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Hurricane Specialists Unit (2009). "Easy to Read HURDAT 1851–2008". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- "Hurricane Alice Nears Bermuda". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. July 4, 1973. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- "Hurricane Alice Hits Bermuda". The Aiken Standard. Associated Press. July 4, 1973. Retrieved November 11, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Alice Leaves Bermuda Mostly Unhurt". The Ledger. Associated Press. July 4, 1973. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- "Canadian Tropical Cyclone Season Summary for 1973". Canadian Hurricane Centre. July 13, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Subtropical Storm Alfa —July 31 – August 2, 1973". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the New England United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- Staff Writer (August 20, 1973). "Hurricane Brenda Heightens Flooding Misery in Mexico". Los Angeles Times.

- Francis B. Kent (August 30, 1973). "Torrential Rains Hamper Hunt for Quake Victims in Mexico". Los Angeles Times.

- United Press International (August 22, 1973). "Brenda Sloshes Into Mexico; 2 Persons Killed". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Tropical Depression Christine —September 2–6, 1973". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- Staff Writer (September 5, 1973). "Flood Warning Closes Schools, Govt. Offices". The Virgin Islands Daily News. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Tropical Depression Eleven — September 8–14, 1973". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Gulf Coast". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Andrew A. Yemma (September 6, 1973). "Delia Threatens Grain Crops". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Tropical Depression Thirteen — September 23–27, 1973". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Robert Simpson (September 25, 1973). "Subtropical Depression Thirteen Bulletin One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- Joseph Pelissier (September 25, 1973). "Tropical Depression Thirteen Bulletin Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- Herbert Saffir (September 27, 1973). "Tropical Depression Thirteen Bulletin Four (Final)". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- National Weather Service in Charleston, South Carolina (September 26, 1973). "South Carolina Special Tide Statement September 26, 1973". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- National Weather Service in Savannah, Georgia (September 26, 1973). "Georgia Special Tide Statement September 26, 1973". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- Rafi Ahmad; Barbara Carby; Bill Cotton; Jerry DeGraff; Norman Harris; David Howell; Franklin McDonald; Paul Manning; Jim McCalpin (January 27, 1999). "Landslide Hazard Mitigation and Loss-reduction for the Kingston Jamaica Metropolitan Area". Caribbean Disaster Mitigation Project. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Staff Writer (2009). "List of Jamaica Hurricanes Between 1871 and 1994". The Jamaica Gleaner. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- National Hurricane Center (2009). "Non-developing Atlantic Depressions 1967–1987". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- National Hurricane Center (April 22, 2009). "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 7, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- National Hurricane Center (February 13, 2007). "Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.