1947 Cape Sable hurricane

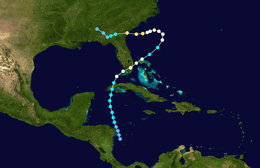

The 1947 Cape Sable hurricane, sometimes known informally as Hurricane King, was a moderate hurricane that caused catastrophic flooding in South Florida and the Everglades in mid-October 1947. The eighth tropical storm and fourth hurricane of the 1947 Atlantic hurricane season, it first developed on October 9 in the southern Caribbean Sea and hence moved north by west until a few days later it struck western Cuba. The cyclone then turned sharply to the northeast, accelerated, and strengthened to a hurricane, within 30 hours crossing the southern Florida peninsula. Across South Florida, the storm produced widespread rainfall up to 15 inches (380 mm) and severe flooding, among the worst ever recorded in the area, that led to efforts by the United States Congress to improve drainage in the region.

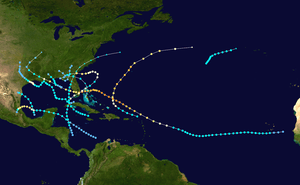

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Storm track | |

| Formed | October 9, 1947 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 16, 1947 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 105 mph (165 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 965 mbar (hPa); 28.5 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 direct, 0 indirect |

| Damage | $3.26 million (1947 USD) |

| Areas affected | Cuba, Florida, The Bahamas, Georgia, South Carolina |

| Part of the 1947 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Once over the Atlantic Ocean on October 13, the storm made history when it was the first to be targeted for modification by government and private agencies; dry ice was spread by airplanes throughout the storm in an unsuccessful effort to weaken the hurricane, though changes in the track were initially blamed upon the experiment. On the same day as that of the seeding, the cyclone slowed dramatically and turned westward, making landfall on the morning of October 15 south of Savannah, Georgia. Across the U.S. states of Georgia and South Carolina, the small hurricane produced tides up to 12 feet (3.7 m) and significant damage to 1,500 structures, but the death toll was limited to one person. The system dissipated the next day over Alabama, having caused $3.26 million in losses along its path.[nb 1]

Meteorological history

In early October 1947, the origins of Hurricane Nine were detected north of Panama in the Intertropical Convergence Zone.[1] On October 9 at 0600 UTC, a minimal tropical storm was estimated to have formed with maximum sustained winds near 40 miles per hour (64 km/h); thereafter it moved north by west.[2] By October 10, the storm accelerated and began strengthening steadily, reaching a peak intensity of 65 mph (105 km/h) before striking land just before 0600 UTC on October 11 south of Pinar del Río in Pinar del Río Province, Cuba.[2] The center of the storm then began turning to the northeast before passing near Batista Field, which recorded wind gusts of up to 57 mph (92 km/h).[1] Six hours after leaving northern Cuba, the storm rapidly became a hurricane, equivalent to Category 1 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.[2] Just after 00 UTC on October 12, the hurricane struck Florida just north of Cape Sable, and just before 1200 UTC it left the Miami metropolitan area near Pompano Beach[3]—the same area that had been hit by the 1947 Fort Lauderdale hurricane one month previous[1][4]—with winds of 85 mph (137 km/h). Unusually, the hurricane strengthened over land as it passed over South Florida, a phenomenon also observed in Tropical Storm Fay (2008), which struck the same region.[2]

After leaving South Florida, the hurricane passed north of the Bahamas while maintaining its intensity, although a lack of weather observations near its eye prevented forecasters from appraising its exact location and movement.[1] Early on October 13, the hurricane slowed substantially and began turning to the north; by afternoon, the cyclone had shifted course and turned westward, toward the Southeastern United States.[2] Early on October 14, a reconnaissance aircraft penetrated the storm but only reported winds of up to 55 mph (89 km/h).[1] As the storm continued moving west, another mission that entered the center around 00 UTC on October 15 reported hurricane-force winds.[1] At 12 UTC that day, the storm struck 15 miles (24 km) south of Savannah, Georgia, with winds of 85 mph (137 km/h).[2] At the time, the coverage of hurricane-force winds was small, extending about 20 miles (32 km) in all directions from the eye.[1] The storm weakened slowly as it crossed inland areas of Georgia, but by 00 UTC on October 16 it weakened to a tropical storm, dissipating 18 hours later over Alabama.[2]

Preparations

By October 12, the U.S. Weather Bureau issued hurricane warnings from the Miami metropolitan area to Vero Beach.[5]

Impact

Florida

Upon striking southernmost Florida, the cyclone produced insignificant wind damage of $75,000 (1947 USD),[1] largely due to its having struck an area hit by the more powerful 1947 Fort Lauderdale hurricane in September.[1][4] Peak winds in Florida were estimated to have reached 95 mph (153 km/h) around Cape Sable, the area where the storm made landfall,[3] though these were not officially accepted as the maximum sustained winds.[2] At the Dry Tortugas, wind instruments reported readings up to 84 mph (135 km/h) before failing due to "friction from lack of oil";[3] higher winds were believed to have occurred thereafter.[1] Elsewhere in South Florida, the U.S. Weather Bureau Air Station at Miami International Airport reported sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h),[3] while the Weather Bureau Office in downtown Miami recorded peak winds of 62 mph (100 km/h).[1] Between the two stations, each 7 mi (11 km) apart, the difference in atmospheric pressure was 3 mb (0.09 inHg), but the lowest pressure was not below 995.3 mb (29.39 inHg).[1] As the storm center passed just north of Fort Lauderdale, the city at 0700 UTC on October 12 reported a pressure of 982.1 mb (29 inHg) that was "still falling" at the time.[6] The eye of the storm by 0830 UTC passed over the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse, which reported calm winds for an hour—the second time in less than a month in which the eye of a hurricane passed over or near the lighthouse, the other having occurred on September 17.[1][4]

Region-wide, the hurricane produced significant rainfall totals of 5 inches (130 mm) to 12 in (300 mm)—and, in the interior, locally as high as 15 in (380 mm)[7]—causing severe flooding.[4] The highest measured rainfall total in 24 hours in South Florida was 14.2 in (360 mm) in northeastern Broward County.[8] At a weather observation site in Hialeah, 1.32 in (34 mm) of rain fell in as little as 10 minutes.[3] In all, as much as 6 in (150 mm) fell in just 1¼ hour in the city;[3][4] due to saturated ground preceding the arrival of the storm, much of the area flooded easily, leaving parts of the city submerged under 6 feet (1.8 m) of water.[3][4] Similarly, "waist deep" depths were reported in nearby Miami Springs, Opa-locka, rural western sections of Pompano Beach, and many other cities of the Miami metropolitan area.[3][9] In Boca Raton, homes in the historic Old Floresta district that housed Army Air Field soldiers were flooded in up to 8 in (200 mm) of water.[10] In the wake of the flooding in his city, Hialeah City Mayor Henry Milander blocked access from surrounding cities.[3] In the Miami area, the Little River and the Seybold Canal overflowed,[3] as did the New River once again in Fort Lauderdale, which had previously done so during the September hurricane.[11] During the storm, up to 11 in (280 mm) of rain in three hours were reported to have fallen on the city of Fort Lauderdale,[11] and sections of Broward County were under 8 ft (2.4 m) of water.[12] On the Tamiami Trail, floodwaters extended all the way across the state from the Miami area to as far west as Everglades City in Collier County.[4] Due to the floods, septic tanks overflowed, leaving canal banks and patches of ground isolated by floodwaters;[11] reportedly, U.S. Route 1, locally called Federal Highway and built largely upon the Atlantic coastal ridge—the highest elevation in South Florida—was flooded out between Miami and Fort Lauderdale.[4] Having been isolated by the floods, deer, rattlesnakes, and other wildlife, along with horses and cattle, sought shelter upon the remaining exposed ground,[11] particularly levee banks.[12]

The flooding that resulted from the storm and the earlier September hurricane was among the worst ever recorded in South Florida and became known as the "Flood of 1947" or, as the South Florida Sun-Sentinel newspaper in 1990 called it, "the Great South Florida Flood."[12] The rains from the storms followed an abnormally wet rainy season in the spring of 1947 that raised the water table to dangerous levels and by July forced several emergency meetings by the Everglades Drainage District (EDD) to address widespread flooding.[9][11] Despite the measures, which resulted in the opening of floodgates to relieve flooded farmlands by diverting water through back-pumping to Lake Okeechobee, lack of funding hampered efforts by EDD Chief Engineer Lamar Johnson to address the situation.[12] After the October hurricane struck Florida, eleven counties extending south from Osceola County, Florida, were at least 50% flooded[1][9]—roughly 90% of the land mass from Orlando to the Florida Keys.[12] South of Lake Okeechobee, a sheet of standing water covering 20 mi (32 km) to 40 mi (64 km) across and ranging from 6 in (0.15 m) to 10 ft (3.0 m) deep inundated much of the region, including the Everglades.[9] In the region, 5,000,000 acres (2,000,000 ha) of land were flooded as abnormally high coastal tides prevented water from being released through canals to the Atlantic Ocean.[12] The flooding divided many communities: near Fort Lauderdale, a temporary dam that had been erected by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to protect Davie—a town in which 90% of the homes by the end of October were at least partially submerged[9]—lowered waters in some areas but merely diverted them to others, flooding a neighborhood and leading to angry complaints by residents; the situation worsened after the October hurricane produced even more rain over flooded South Florida.[12]

Georgia and South Carolina

Upon making landfall, the storm produced high tides of up to 12 ft (3.7 m) at Parris Island, South Carolina, and 9 ft (2.7 m) at Charleston, South Carolina. Up to 1,500 or more buildings were significantly damaged due to wind gusts that reached 95 mph (153 km/h) at Savannah, Georgia. One person died due to high tides preceding the storm. Total property losses in Georgia and South Carolina reached $2,185,000 (1947 USD).[13]

Aftermath

In South Florida, the flooding from the September and October hurricanes led to the creation in 1949 of what is now the South Florida Water Management District, which under a Congressional plan was entrusted with the task of preventing a recurrence of significant flooding by forming an improved flood-control system to modulate the water table and by providing suitable water levels with which to water crops, prevent saltwater intrusion, and support recreational opportunities as well as the growing South Florida communities.[9][11][12] Large pumping systems were constructed, along with numerous new levees and canals, to mitigate the risk of large-scale flooding, yet population growth since the late 1940s is believed to have reduced the extent of vacant lands needed for effective drainage, thereby increasing the risk of damage during a flood similar to that of 1947.[4] In his 1974 book Beyond the Fourth Generation, former EDD Chief Engineer Lamar Johnson voiced his concerns about large-scale development near the levees, which separate the Everglades water conservation areas from the Miami metropolitan area. Johnson wrote, "It is my opinion...that anytime that area gets a foot or more of rainfall overnight, the shades of 1947's flood will be with them again."[14]

The cyclone was historically significant in that it was the first tropical cyclone to be modified as part of a multi-year operation called Project Cirrus.[3][4] In July 1946, General Electric (GE) scientists concluded after experimentation that dry ice seeding could induce heavy rainfall and thus ultimately weaken storms by cooling temperatures in the eye.[4] To undertake Project Cirrus, GE, the United States Army, the Office of Naval Research, and the U.S. Weather Bureau functioned jointly on research and planning.[3] Early on October 13, 1947, 200 pounds (3,200 oz) of dry ice were dropped throughout the storm, then located about 350 mi (560 km) east of Jacksonville, Florida. While the appearance of the clouds changed, the initial results of the seeding were inconclusive. Shortly after the seeding took place, the hurricane turned sharply toward the Southeastern United States. While the move the leading GE scientist later blamed upon the seeding, subsequent examination of the environment surrounding the storm determined that a large upper-level ridge was in fact responsible for the abrupt turn.[4]

Following the phonetic alphabet from World War II, the U.S. Weather Bureau office in Miami, Florida, which then worked in conjunction with the military, named the storm King,[3][4] though such names were apparently informal and did not appear in public advisories until 1950, when the first Atlantic storm to be so designated was Hurricane Fox.[4]

Notes

- All damage totals are in 1947 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- Sumner, H. C. (December 1947). "North Atlantic hurricanes and tropical disturbances of 1947" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 75 (11): 251–55. Bibcode:1947MWRv...75..251S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1947)075<0251:NAHATD>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Barnes, pp. 174‑80

- Norcross, Bryan (2007). Hurricane Almanac: The Essential Guide to Storms Past, Present, and Future. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0312371524.

- "Flooded Miami in Hurricane Path". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. October 12, 1947. p. 1. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- "none". Miami Herald. October 12, 1947. p. 1.

- Kleinberg, p. 220

- Schoner, R. W.; S. Molansky (July 1956). National Hurricane Research Project Report No. 3: Rainfall Associated With Tropical Cyclones (And Other Disturbances) (Pre-printed) (Report). National Hurricane Research Project. Washington, D.C., NOAA Central Library. pp. 170–71. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- "Three 1947 Storms Produced Record Rainfall". Miami Herald. September 3, 1978.

- Ling, p. 180

- McIver, pp. 135–7

- "The Great South Florida Flood". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. September 9, 1990.

- "Severe Local Storms for October 1947" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. U.S. Weather Bureau. 75 (10): 203–4. September 1947. Bibcode:1947MWRv...75..203.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1947)075<0203:SLSFO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- Johnson, Lamar (1974). Beyond the Fourth Generation. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813003986.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Jay (1998). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill Press. ISBN 0-8078-2443-7.

- Bush, David M., et al. (2004). Living With Florida's Atlantic Beaches. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822332892.

- Churl, Donald W., and John P. Johnson (1990). Boca Raton: A Pictorial History. The Downing Company Publishers. ISBN 0-89865-792-X.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). Significant Tornadoes, 1680-1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. Environmental Films. ISBN 978-1879362031.

- Kleinberg, Eliot (2003). Black Cloud: The Deadly Hurricane of 1928. Carroll and Graf Publishing. ISBN 0-7867-1386-0.

- Ling, Sally J. (2005). Small Town, Big Secrets: Inside the Boca Raton Army Air Field During World War II. History Press. ISBN 1-59629-006-4.

- McIver, Stuart (1983). Fort Lauderdale and Broward County: An Illustrated History. Fort Lauderdale Historical Society. ISBN 978-0897810814.

- Norcross, Bryan (2007). Hurricane Almanac: The Essential Guide to Storms Past, Present, and Future. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0312371524.