1943 Argentine coup d'état

The 1943 Argentine coup d'état, also known as the Revolution of '43, was a coup d'état on June 4, 1943, which ended the government of Ramón Castillo, who had been fraudulently elected to the office of vice-president,[1] as part of the period known as the Infamous Decade. The military was opposed to Governor Robustiano Patrón Costas, Castillo's hand-picked successor, a major landowner in the Salta Province and a primary stockholder in the sugar industry. The only serious resistance to the military coup came from the Argentine Navy, which confronted the advancing army columns at the Navy Petty-Officers School of Mechanics.

A newspaper announcing the beginning of the coup. | |

| Date | 4 June 1943 |

|---|---|

| Location | Argentina |

| Also known as | Revolution of '43 |

| Outcome | End of the Infamous Decade Military dictatorship established |

Antecedents

Two primary factors influenced the coup of 4 June 1943: The Infamous Decade that preceded it and World War II.

The Infamous Decade (1930–1943)

What is known as the Infamous Decade began on September 6, 1930 with the military coup led by the corporatist, catholic-nationalis General Jose Felix Uriburu. Uriburu overthrew President Hipólito Yrigoyen, a member of the Radical Civic Union party, who had been democratically elected in 1928 to serve his second term. On September 10, 1930, Uriburu was recognized as de facto president of the nation by the Supreme Court.[2] This court order laid the foundation for the doctrine of de facto governments and would be used to legitimize all other military coups.[3] The de facto government of Uriburu outlawed the Radical Civic Union.

The local elections of Buenos Aires on 5 April 1931, had an unexpected result for the government. The radical candidate, Honorio Pueyrredón, won the election despite the national party's confidence of their own victory and despite the radical party's lack of leadership. Although the radical party still lacked a few votes in the electoral college and the national party could still negotiate with the socialists to prevent the radicals from winning the governorship, the government began to panic. Uriburu reorganized the cabinet and appointed ministers from the "liberal" sector. He cancelled the local government elections for the provinces of Córdoba and Santa Fe. On 8 May 1931 he cancelled the appeal to the provincial electoral college, and on 12 May, he named Manuel Ramón Alvarado[4] as de facto governor of Buenos Aires.[5]

A few weeks later, a revolt led by Lieutenant Colonel Gregorio Pomar, broke out in the province of Corrientes. Although the revolt was rapidly brought under control, it gave Uriburu the excuse he was looking for. He closed all the premises of the Radical Civic Union, arrested dozens of its leaders, and prohibited the electoral colleges from electing politicians that were directly or indirectly related with Yrigoyen. Because Pueyrredón had been a minister of Yrigoyen, this meant that he could not be elected. However, Uriburu also exiled Pueyrredón from the country with Alvear, a prominent leader of the radical party.[5] In September he called for elections in November and shortly after, he annulled the elections in Buenos Aires.[6][7]

After the failure of the corporatist effort, Argentina was governed by the Concordancia, a political alliance formed between the conservative National Democratic Party, the Antipersonalist Radical Civic Union, and the Independent Socialist Party. The Concordancia governed Argentina during the Infamous Decade (1932–1943), throughout the presidencies of Agustín Pedro Justo (1932–1938), Roberto María Ortiz (1938–1940), and Ramón Castillo (1940–1943). This period was characterized by the beginning of a new economic model known as Import substitution industrialization.

In 1943, elections for a new president had to be held, and an attempt to fraudulently award the presidency to the sugar entrepreneur Robustiano Patrón Costas, a powerful figure in the Salta Province during the previous four decade, was evaded. Costas's assumption of the presidency would have secured the continuation and deepening of the fraudulent regime.

The Second World War

The Second World War (1939–1945) had a decisive and complex influence on Argentinian political events, particularly on the coup of 4 June 1943.

At the time when the second world war began, Great Britain had a pervading economic influence in Argentina. On the other hand, the United States had secured its hegemonic presence throughout the entire continent and was preparing to permanently replace Great Britain as a hegemonic power in Argentina. The war brought about an ideal moment for the U.S., especially from the moment it abandoned neutrality due to Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

Argentina had a long tradition of neutrality regarding European wars, which had been sustained and defended by every political party since the 19th century. The reasons for Argentinian neutrality are complex, but one of the most important is connected with its position of food supplier to Britain and to Europe in general. In both the first as well as the second world war, Great Britain needed to guarantee the provision of food (grain and meat) for its population and its troops, and this would have been impossible if Argentina had not maintained neutrality, since the cargo ships would have been the first to be attacked, thus interrupting the supply. At the same time, Argentina had traditionally maintained a skeptical stance toward the hegemonic vision of Pan-Americanism that had driven the United States since the 19th century.

In December 1939 the Argentine government consulted with Britain on the possibility of abandoning neutrality and joining the Allies. The British government flatly rejected the proposition, reiterating the principle that the main contribution of Argentina was its supplies and in order to guarantee them it was necessary to maintain neutrality. At that time the United States also held a neutral position strengthened by the Neutrality Acts and its traditional Isolationism, although that would change radically when Japan attacked its military bases in the Pacific.

In the wake of Pearl Harbor, at the Rio Conference of 1942, the United States called upon all Latin American countries to enter the war en bloc. For the United States, which was not affected by the interruption of trade between Argentina and Europe, World War II was presented as an excellent opportunity to finish imposing its continental hegemony, both politically and economically, and permanently displace Great Britain from its stronghold in Latin America. But Argentina, through its chancellor, Enrique Ruiz Guiñazú, opposed entering the war, curtailing the U.S. proposal. From this point on, the American pressure would not stop growing until it became unbearable.

Faced with war, the Argentine population divided into two large groups: "pro-allies" (aliadófilos) and "pro-neutral" (neutralistas). The first group was in favor of Argentina entering the war on the side of the allies, while the latter argued that the country should remain neutral. A third group of "pro-Germans" (germanófilos) remained a minority; because it was extremely unlikely that Argentina would enter the war on the side of the Axis, they tended support neutrality.

The two previous presidents, Radical Antipersonalist Ortiz (1938–1942) and National Democrat Castillo (1942–1943), had maintained neutrality, but it was clear that Patrón Costas, the official presidential candidate, would declare war on the Axis. This circumstance had an enormous influence on the armed forces, above all the army, where the majority favored neutrality.

Economic and Social Situation

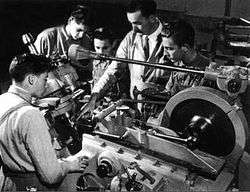

One of the direct consequences of the Second World War on the Argentine state of affairs was the economic boost that resulted from industrialization. In 1943, for the first time, the index of industrial production surpassed that of agricultural production.[8] Spearheaded by the textile industry, industrial exports increased from 2.9% of the total in 1939 to 19.4% in 1943.[9]

The number of industrial workers grew by 38%, from 677,517 in 1941 to 938,387 in 1946.[10] The factories were concentrated mostly in the urban area of Greater Buenos Aires, which in 1946 comprised 56% of industrial establishments and 61% all workers in the country.[11]

On the other hand, the Great Depression had limited the influx of European immigrants, so that a new influx of migrants due to rural flight was completely transforming the working class, both in terms of numbers and in terms of culture. In 1936, 36% of the population of Buenos Aires were foreigners and only 12% were migrants from elsewhere in Argentina (rural areas and small cities). By 1947, foreigners had fallen to 26% and domestic migrants had more than doubled to 29%.[12] Between 1896 and 1936 the average annual number of provincials arriving in Buenos Aires was 8,000; that average amounted to 72,000 between 1936 and 1943 and 117,000 between 1943 and 1947.[13]

The new socioeconomic conditions and the geographical concentration anticipated great sociopolitical changes with their epicenter in Buenos Aires.

The Coup of 4 June 1943

Although the Argentine Armed Forces had been one of the pillars that sustained the successive governments of the Infamous Decade, its relationship with power had deteriorated over the last few years because of the change in its generational makeup and, above all, the progress of industrialization process that began in that decade. The development of industry in Argentina (and in many parts of the world) was intimately related to the Armed Forces and the needs of national defense.

President Ramón Castillo had faced several military conspiracies and failed coups, and at that time several civic-military conspiracies were taking place (such as the United Officers Group, led by the radical Ernesto Sanmartino and General Arturo Rawson,[14] and the operations carried out by the radical unionist Emilio Ravignani).

Nevertheless, the coup of 4 June 1943 was not foreseen by anyone and was carried out with a great deal of improvisation and, unlike the other coups that had occurred in the country, almost without civil participation.[15] According to historian José Romero, it was a "rescue maneuver of the group committed to the Nazi infiltration, complicated by its preventing Castillo from turning toward the United States.[16]

The concrete event that triggered the military coup was President Castillo demanding on 3 June that his Minister or War, General Pedro Pablo Ramírez, resign for having met with a group of leaders from the Radical Civic Union, who offered to nominate him for president in the upcoming election. General Ramírez was to be the presidential candidate of the Democratic Union, an alliance that the moderate wing of the Radical Civic Union was trying to form with the Socialist Party and the Democratic Progressive Party, with the help of the Communist Party.[17]

The coup was decided the day before at a meeting in Campo de Mayo led by Generals Rawson and Ramírez. Neither General Edelmiro Julián Farrell nor Colonel Juan Perón, both of whom would go on to lead the Revolution of 43, participated in the meeting: Farrell because he excused himself for personal reasons and Perón because he could not be found.[18]

At dawn on 4 June, a military force of 8000 soldiers set out from Campo de Mayo, led by Generals Rawson and Elbio Anaya, Colonels Ramírez and Fortunato Giovannoni, and Lieutenant Colonel Tomás A. Ducó (famously the president of the sports club CA Huracán). Upon arriving at the Navy Petty-Officers School of Mechanics in the neighborhood of Núñez, the group was attacked by loyal forces who were entrenched there, resulting in 30 killed and 100 wounded.[19] Having surrendered the Navy School of Mechanics, President Castillo boarded a trawler with orders to head toward Uruguay,[20] abandoning the Casa Rosada, where Generals Ramírez, Farrell, and Juan Pistarini. The generals received the rebel army shortly after noon, and Rawson declared himself president.[21]

At first, the coup was supported by all political and social forces, with more or less enthusiasm, with the sole exception of the Communist Party.[22] Britain and the United States supported it as well, welcoming the coup "with shouts of satisfaction", according to Sir David Kelly, the British ambassador to Argentina at the time.[23] The German embassy, on the other hand, burned its files the previous day.[24]

The Organizers of the Coup and the role of the United Officers' Group

At the time, the Argentine armed forces of consisted of only two groups: the Army and the Navy. The navy was generally made up of officers from the aristocracy and upper class.. The army, on the other hand, was undergoing major changes in its composition with the emergence of new groups of officers from the middle class, new ideas concerning defense related to the demands of industrialization and military businesses, and the need for the State to have an active role in promoting these activities.

The Army was divided into two major groups: nationalists and classical liberals. While neither group was homogenous, the nationalists did share a common concern for the development of national industry, relations with the Catholic Church, and the existence of an autonomous international position. Many of them had close ties to radicalism, and they tended to come from middle-class backgrounds. The liberals, on the other hand, desired rapprochement with the large economic powers, mainly the United Kingdom and the United States, and upheld the premise that the country should have a production structure based primarily on agriculture and livestock; many came from or belonged to the upper class.

The great political, economic, and social changes that had taken place during the 1930s prompted the emergence of numerous groups with new focuses, not only in the armed forces but in all political and social sectors. This diversity of views was kept under control by General Agustín Pedro Justo's undisputed leadership in the military. But Justo's death on 11 January 1943 left the army without the stability provided by his leadership, unleashing a process of realignments and internal struggles among the various military groups.

Most historians agree that the United Officers' Group (GOU)— a military association created in March 1943 and dissolved in February 1944— played a crucial role in the organization of the coup and in the military government that emerged from it.[25] More recently, however, some historians have questioned the actual influence of the GOU, referring to it as a "myth".[26] American historian Robert Potash, who has studied in detail the actions of the army in modern Argentine history, has greatly deemphasized the participation of the GOU in the 4 June coup.[27] Historians do not agree on many of the particulars of the GOU, but there is consensus that it was a small group of officers, a significant portion of whom were lower-ranking, especially colonels and lieutenant colonels. The GOU lacked a precise ideology, but all its members shared a nationalist, anticommunist, neutralist view of the war and highly concerned with ending the open acts of corruption of the conservative governments.

Potash and Félix Luna have claimed that the groups' founders were Juan Carlos Montes and Urbano de la Vega. It is also known that the Montes brothers were active radicals and patricians, with close relations with Amadeo Sabattini, who was a close friend of Eduardo Ávalos.[28] Conversely, the historian Roberto Ferrero maintains that the two "brains" of the GOU were Enrique González and Emilio Ramírez.[29] Lastly, Pedro Pablo Ramírez and Edelmiro Farrell also had close contacts with the GOU; its first and only president was Ramírez's father.

Regardless of the debate over the true influence of the GOU on the Revolution of 43, the armed forces, particularly after the death of General Justo, was an unstable conglomeration of relatively autonomous groups with indeterminate ideologies who were developing relationships with the old and new powers, and who would go on to assume definite positions as the process unfolded.

Rawson's brief dictatorship

General Arturo Rawson was a zealous catholic and member of the conservative National Democratic Party, and hailed from a traditional family of the Argentine aristocracy. Rawson led a group of conspirators known as "Jousten generals", because of the Jousten Hotel where they gathered on 25 May.

The group consisted of military men who hold important positions in the government that arose after the coup: General Diego Isidro Mason (agriculture), Benito Sueyro (navy), and his brother Sabá Sueyro (vice president). Also part of the group was Ernesto Sammartino (Radical Civic Union), who was summoned by Rawson after the coup to organize the cabinet. However, since no one informed Rawson of his presence once he arrived at the Casa Rosada, he returned home after waiting for a reasonable time.[30]

The problem arose the following day when Rawson communicated to the military leaders the names of the people who would be part of his cabinet. Among them were three personal friends who were known members of the right-wing and even connected with the deposed regime: General Domingo Martínez, José María Rosa (his son), and Horacio Calderón. The military commanders, who otherwise would have remained deliberative throughout the revolution, flatly rejected the nominations, and Rawson's insistence on keeping them led to his resignation on June 6. Ramírez then took over, precisely who had unleashed the coup to be removed by Castillo after his meeting with the radicals to offer him the candidacy for the Democratic Union.[31]

Two years later, in 1945, Rawson would attempt to organize a coup against Farrell and Perón, which would prove to be a failure, but which opened the way for General Ávalos and the Campo de Mayo officers who led to the resignation and detention of Perón, in the week prior to the popular demonstrations on 17 October.[32]

Ramírez's dictatorship

On June 7, General Pedro Pablo Ramírez swore in as President and Sabá Sueyro as Vice-President. He would go on to serve as president during the first eight months of the Revolution of 43. Ramírez had been Castillo's Minister of War and, a few days before the coup, had been invited by a radical faction to lead the ticket of an opposition alliance, the Democratic Union. Its first cabinet was formed entirely by the military with the sole exception of the Minister of Finance:[33]

- Ministry of Economy and Public Finances: Jorge Santamarina

- Ministry of the Interior: Colonel Alberto Gilbert

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Rear Admiral Storni Second;

- Ministry of Justice: Colonel Elbio Anaya

- Ministry of the Navy: Rear Admiral Benito Sueyro

- Ministry of the Army: General Edelmiro J. Farrell

- Ministry of Agriculture: Brigadier General Diego I. Mason

- Ministry of Public Works: Vice Admiral Ismael Galindez

No members of the GOU were appointed to the cabinet, but two received other important positions: Colonel Enrique González in the private secretariat of the presidency and Colonel Emilio Ramirez, the president's son, as the Buenos Aires Chief of Police. These two, along with Colonel Gilbert and Rear Admiral Sueyro, would form President Ramirez's inner circle.[33]

Initial steps

The first measures taken by the Ramirez and Rawson governments limited individual freedoms and repressed political and social groups. Since the date of the coup, the new authorities carried out arrests of communists leaders and militants, most of whom were housed in prisons in Patagonia, while others were able to go into hiding or exile in Uruguay.[34]

On 6 June, the directors of the Workers' Federation of the Meat Industry were detained and sent to the South. Their premises were shut down and Secretary General José Peter was imprisoned without trial for a year and four months. In July, the government dissolved the Second General Confederation of Labour (CGT), a group of labor unions who supported the Socialist and Communist parties after splitting from the First General Labor Confederation in October 1942.[35]

On 15 June, the government dissolved the pro-allied association Acción Argentina. In August, it passed a set of rules that solidified State control over trade unions. On 23 August, it appointed an "interventor" (a kind of supervisor and inspector) to the Railway Union who supplanted its leaders.

The government dissolved congress and took control of the National University of the Littoral. These measures would lead to a confrontation with broad political and social sectors, particularly the student movement.

Alongside these measures, the Rawson administration decreed that rural rents and leases be frozen, which had a positive effect on workers and farmers, and created a committee to investigate the CHADE scandal, an occurrence during the Infamous Decade in which the Hispano-American Electrical Company (CHADE) bribed government officials to give them a monopoly of electrical services in Buenos Aires. The committee, whose mission was to delve into the fight against corruption, published the well-known Rodríguez Conde Report in 1944, proposing two decrees to remove CHADE's status as a legal person. Nevertheless, the report was not published until 1956, and the projects were not even dealt due to the decision of the de facto vice-president Juan D. Perón.[36] CHADE was one of the few non-nationalized companies during the Perón administration (1946–1955), since it had contributed to Perón's election campaign.[37]

Storni's Resignation

In those first months an incident occurred which would lead to the resignation of Admiral Segundo Storni, the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Storni was one of the few members of the Argentine military at the time who was sympathetic to the United States, where he had lived several years. Although he was a nationalist, he was also a supported of the Allies and favored Argentina's entry in the war on their behalf. On 5 August 1943, he sent a personal letter to the U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull, anticipating that Argentina intended to break relations with the Axis powers, but also beseeching his patience while he created a climate of rupture in the country. At the same time, Storni made a gesture to the United States regarding the supplying of arms, thus isolating the neutralists. With the intention of putting pressure on the Argentine government, Hull made the letter public and further questioned the Argentina's tradition of neutrality in harsh terms.[38]

This action had the opposite effect of what Hull intended, provoking a recrudescence of the already powerful anti-American sentiment —especially in the armed forces— thus bringing about Storni's resignation and replacement by a "neutralist," Coronel Alberto Gilbert, who was then acting as Minister of the Interior. In order to fill the later position, Ramírez appointed a member of the GOU, Colonel Luis César Perlinger, a Hispanic-Catholic nationalist who would lead the right-wing reaction against Farrell and Perón in the following years.

Storni's resignation carried with it the resignations of Santamarina (Minister of Economy and Public Finances), Galíndez (Public Works), and Anaya (Justice), and opened the doors in the government to the far-right faction of Hispanic-Catholic nationalists, to which the new Minister of Education, the writer Hugo Wast also belonged. Until then, despite the pressure from the nationalists, Ramírez had permitted "liberal" leaders to remain in their appointed positions; but the fall of Storni and the rise of Perlinger brought about nationalist hegemony in the government.

Educational politics and student opposition

The Revolution of 43 handed the management of education over to the right-wing Hispanic-Catholic nationalist. The process began on July 28, 1943 when the government took control of the National University of the Littoral. The University Federation of the Littoral protested vehemently against the appointment of Jordán Bruno Genta, to which the government responded by detaining its secretary general and expelling students and professors who protested in opposition.

The Argentine university was governed by the principles of the University Reform of 1918, which established the university autonomy, the participation of students in the university government, and academic freedom. Genta, known for his far-right and anti-reformist ideas, maintained that the country needed to create "an intelligent aristocracy, nourished by Roman and Hispanic lineage".[39] These declarations produced the first confrontation among the forces that adhered to the Revolution of 43, when the radical nationalist group FORJA, which supported the Revolution, harshly criticized Genta's statements, of Genta deeming them "the highest praise to the university banditry that has trafficked with all the goods of the Nation."[40] Because of these declarations, the military government imprisoned its founder Arturo Jauretche.[41]

Although Genta was forced to resign, the conflict between the government and the student movements became widespread and polarized the extremes, while the nationalist Hispanic-Catholic faction continued to advance and occupy important position in the government. By October, Ramírez had taken control of all universities heightened the role of right-wing catholic nationalism with the inclusion of ministers Perlinger and Martínez Zuviría, at the same time declaring the Argentine University Federation to be outside the law.

The group'sultramontanist, hispanist, elitist, anti-democratic, and anti-feminist ideology was defined through several provocative statements.

Sarmiento brought three plagues to this country: Italians, sparrows and teachers.[42]

Lay education is an invention of the devil.[42]

We must cultivate and affirm our differentiated personality, which is Creole, and thus Hispanic, catholic, apostolic and roman.[43]

It is from this period that most of the disputes between the military government and university students are usually cited.

Among the officials of right-wing Catholic-Hispanic nationalism who held government positions during the Revolution of 43 were Gustavo Martínez Zuviría (Minister of Education), Alberto Baldrich (Minister of Education), José Ignacio Olmedo (National Council of Education), Jordán Bruno Genta, Salvador Dana Montaño (the National University of the Littoral "interventor"), Tomás Casares (University of Buenos Aires "interventor"), Santiago de Estrada (National University of Tucumán "interventor"), Lisardo Novillo Saravia (National University of Córdoba "interventor"), Alfredo L. Labougle (National University of La Plata rector), and Juan R. Sepich (director of the National School of Buenos Aires).

On 14 October 1943, a group of 150 political and cultural figures led by the scientist Bernardo Houssay signed a Statement on Effective Democracy and Latin American Solidarity, calling for elections and the country's entry into the war against the Axis.[44] Ramírez responded by dismissing those signers who were employees of the State.

November 1943: emergence of Perón and union leadership

.jpeg)

Historians have diverse opinions on the degree that Juan Perón had on Argentine politics prior to 27 October 1943, when he assumed the management of the insignificant Department of Labor.[45] What is certain is that this was the first state department directed by Perón and that shortly after he became a figure of public importance and labor unions came to the forefront of national politics.

The Ramírez administration had assumed a similar position toward unions as had previous governments: granting of little political and institutional importance, widespread non-compliance with labor laws, pro-employer sympathies, and punitive repression.

In 1943, the Argentine Workers Movement was the most developed in Latin America at the time, consisted of four major groups: the first General Confederation of Labour or 1st CGT (mostly socialists and radical syndicalists), the 2nd CGT (socialists and communists), the small Argentine Labor Union (radical syndicalists), and the almost nonexistent Regional Workers' Federation (anarchists). One of Ramírez's first moves was to dissolve the 2nd CGT, which was headed by the socialist Francisco Pérez Leirós, and which contained important unions like the, directed by the socialist Ángel Borlenghi, and various communist unions (construction, meat, etc.). Paradoxically, this measure had the immediate effect of strengthening the 1st CGT, also headed by a socialist, as many members of the defunct 2nd CGT went to join it.

Shortly after the government sanctioned a legislation on unions, that, although it fulfilled some of the unions expectations, at the same time allowed the State to take control of them. The Ramírez government then made use of this law to take control of the powerful railway unions who formed the core of the CGT. In October, a series of strikes were answered with the arrest of dozens of workers' leaders. It soon became apparent that the military government was composed of influential anti-union factions.

From the moment the coup took place, the labor movement had begun to discuss a strategy of cooperating with the military government. A number of historians, including Samuel Baily,[46] Julio Godio, and Hiroshi Matsushita,[47] have shown that the Argentine labor movement had evolved from the late 1920s to a labor nationalism,[48] which entailed a greater commitment of unions to the state.

The first step was taken by the leaders of the 2nd CGT, headed by Francisco Perez Leirós, who met with the Minister of the Interior, General Alberto Gilbert. The unionists asked the government to call an election and offered the support of a union march to the Casa Rosada, but the government rejected the offer and dissolved it.[49]

Shortly afterwards another union group headed by Ángel Borlenghi (socialist and secretary general of the powerful Commerce and Trade Workers in the 2nd CGT 2), Francisco Pablo Capozzi () and Juan Atilio Bramuglia (Railway Union), opted, albeit with reservations and distrust, to establish relations with a sector of the military government more inclined to accept union demands, with the aim of forming an alliance capable of influencing the course of events. The person chosen for the initial contact was Colonel Domingo Mercante, the son of an important railroad union leader and member of the GOU. In turn, Mercante summoned his political partner and close friend, Juan Perón.[50]

The unionists suggested that the military the create a Secretariat of Labor, strengthen the CGT, and sanction a series of labor laws that would accept the historical claims of the Argentine labor movement. At that meeting, Perón attempted to synthesize the various claims, defining it as a policy to "dignify work".[51]

From then on colonels Perón and Mercante began to meet regularly with the unions. On 30 September 1943 they held a public meeting with 70 union leaders on the occasion of a general revolutionary strike declared by the CGT for October, supported by all the opposition. Communist unionists demanded, as a precondition for any dialogue with the government, the liberty of José Peter, Secretary General of the Butcher's Union, who had recently been imprisoned for a strike in the slaughterhouses. Perón intervened personally in the conflict, pressured the companies to reach a collective agreement with the union (the first in the sector) and achieved the liberation of the Communist leader.[52] On the other hand, Alain Rouquié points out that in the negotiations brought to a close by colonels Perón and Mercante resulted in an agreement with the new Autonomous Butcher's Union of Berisso and Ensenada, in open opposition to the communist Workers' Federation of the Meat Industry.[53]

The effect on the labor movement was remarkable and the group of unionists in favor of an alliance wit the military government grew, incorporating other socialists like José Domenech (railroad), David Diskin (commerce), Alcides Montiel (brewer), Lucio Bonilla (textile); revolutionary syndicalists from the Argentine Labor Union, such as Luis Gay and Modesto Orozo (both telephone); and even some communists like René Stordeur, Aurelio Hernandez (health)[54] and Trotskyists Ángel Perelman (metallurgy). One of the first effects of the new relationship established between labor unions and the military was the unions' refusal to participate in the general revolutionary strike, which went unnoticed.

Shortly afterwards, on 27 October 1943, the precarious alliance between unionists and the military led Ramirez to appoint Perón as Head of the Department of Labor, a position of no value whatsoever. One of his first measures was to remove the "interventors" from the railway unions and nominate Mercante in their place. At the same time, the Central Committee of the CGT, made up of socialists, decided to create a Commission for Labor Union Unity with the purpose of restoring a single central, traditional objective for the Argentine labor movement[55]

A month later, Perón, with the help of General Farrell, managed to get President Ramírez to approve the creation of a Secretary of Labor and Projections, with a status similar to that of a ministry and a direct dependence on the president.[56]

As Secretary of Labor Perón did a remarkable work, approving the labor laws that had been claimed historically by the Argentine labor movement (extending the severance indemnity that existed since 1934 for commerce employees, pensions for commerce employees, a multi-clinic hospital for railway workers, technical schools for workers, the prohibition of employment agencies, the creation of the labor courts, Christmas bonuses), lending efficacy to the existing labor inspectors and impelling for the first time collective bargaining, which grew to become the basic way of regulating the relationship between capital and labor. Moreover, the decree regarding unions associations sanctioned by Ramírez in the first weeks of the revolution, which was criticized by the entire labor movement, was dropped.

In addition, Perón, Mercante, and the initial group of unionists who formed the alliance began to organize a new union that would assume a nationalist-labor identity. The group assumed an anti-communist position already existing in the 1st CGT and, relying on the power of the Secretary of Labor, organized new unions in the industries which lacked them (chemicals, electricity, tobacco) and set up rival unions in industries with powerful communist unions (meat, construction, textiles, metallurgy).

Abandonment of neutrality and crisis of the Ramírez Administration

By early 1944, Perón's alliance with the unions led to the first major internal division among the military. Essentially there were two groups:

The first, led by Ramirez, General Juan Sanguinetti ("interventor" of the crucial Buenos Aires Province) and colonels Luis César Perlinger, Enrique P. Gonzalez, and Emilio Ramirez, relied on Catholic right-wing Catholic-Hispanic nationalism and questioned Perón's pro-worker labor policy. It succeeded in attracting other factions from diverse backgrounds, who expressed their concern about the advance of unions in the government, and it essentially aimed at dismissing Farrell and replacing him with General Elbio Anaya.[57]

The second, led by Farrell and Perón, did not support Ramirez and had initiated a strategy of endowing the Revolution of 43 with a popular base, intensifying on the one hand the successful alliance with the unions in the direction of forming labor nationalism and, on the other, seeking support in political parties, mainly the intransigent radicals and specifically Amadeo Sabattini, in order to consolidate the economic nationalism present in Yrigoyenismo.[57]

Ferrero argues that the Farrell and Perón attempted to form a "popular nationalism" aimed at a democratic exit from the regime, which confronted the non-democratic "elite nationalism" that supported Ramírez.[58]

In addition to this internal division of military power, the government faced an international situation that was utterly unfavorable to them and that left them completely isolated. At the beginning of 1944 it was evident that Germany would lose the war and the pressure of the United States for Argentina to abandon neutrality was already unbearable.

The process was broke out on 3 January 1944, when Ramirez recognized the new Bolivian government, the result of a coup led by Gualberto Villarroel. Bolivia declared itself in favor of neutrality and proposed creating a neutral Southern Bloc with Argentina and Chile, the only Latin American countries that had remained neutral. Exacerbating this was the scandal over the British arrest of the sailor Osmar Helmuth, a German secret agent who had been sent by Ramirez, Gilbert, and Sueyro to buy arms from Germany. The United States reacted forcibly, denouncing Argentina's support of the Bolivian coup and sending at an aircraft carrier as a threat to the La Plata River. Washington's reaction caused the Argentine military leaders to backpedal, and, on 26 January 1944, Argentina broke off diplomatic relations with Germany and Japan.[59]

The severance of diplomatic relations occasioned a crisis in the government, due to the generalized discontent in the armed forces—particularly among the right-wing Catholic-Hispanist nationalist faction, Ramírez's base. Hugo Wast then resigned as Ministry of Education, and Tomás Casares resigned as "interventor" of the University of Buenos Aires. Shortly after, Ramirez's main supporters— his son Emilio and Colonel Gonzalez— also resigned, followed by Colonel Gilbert the next day. The president's hours were numbered.

The fall of Ramirez

By 22 February the GOU had already decided to overthrow Ramirez for his severing diplomatic relations with the Axis powers; since the GOU had sworn to support the president, they simply dissolved it, thus releasing them from their oath. The officers met again the following day again to demand Ramírez's resignation, which he finally conceded to two week later.

On 24 February, in an attempt to anticipate the events, Ramirez called for the resignation of General Farrell, Vice-President and Minister of War. He responded by summoning the main garrison chiefs to his office and ordering them to surround the presidential residence. On the same night, the garrison chiefs near Buenos Aires appeared before Ramirez and demanded his resignation. Ramirez then presented a waiver of resignation in which he invoke "fatigue" as a reason for "delegating" the office of President to Farrell, who became interim President on February.[60]

However, Ramirez was formally still president and continued to operate alongside his closest circle. A few days later, 21 generals met to discuss an electoral exit (among them were Rawson, Manuel Savio, and Elbio Anaya.). Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Tomás Adolfo Ducó, convinced that the generals' meeting intended to launch a coup to support Ramirez, called upon the strategic Infantry Regiment 3 and directed them to the city of Lomas de Zamora, where they took the key buildings and positions and entrenched themselves there. The next day he surrendered.[61]

On 9 March General Ramirez presented his resignation in an extensive document, disseminated publicly, in which he recounts all the steps that led to his deposition.[62] On the basis of the document, the United States refused to recognize the new government and withdrew its ambassador in Buenos Aires, pressuring Latin American countries and Great Britain to do the same.[63]

On 25 February 1944, Farrell assumed the presidency, first temporarily and after March 9 definitively.[64]

Dictatorship of Edelmiro Farrell

General Edelmiro Julián Farrell had been appointed Vice President on October 15, 1943, following the death of the former Vice President Sabá Sueyro. His government was characterized by a twofold tension: he represented an army that was mostly neutralist, but it was becoming impossible to resist the increasing pressure from the United States to join the Allies unconditionally.

Farrell found himself immediately confronted by General Luis César Perlinger, Minister of the Interior and supporter of right-wing Hispanic-catholic nationalism. Farrell's biggest help would be Perón, who he managed to appoint as Minister of War in spite of the opposition from the majority of ex-GOU members, who, alarmed by Perón's ties with labor unions, managed to appoint General Juan Sanguinetti for this position, a decision which Farrell reversed.[64]

At the end of May, Perlinger attempted to start the path to displace the Farrell-Perón team by proposing suggesting that the members of the former GOU fill the vacancy of vice-president. However, against expectations, he lost internal voting among the officers. On June 6, 1944, Perón took advantage of Perlinger's false step to ask for his resignation, to which he immediately agreed. Lacking any alternatives, Perlinger resigned and Perón himself was appointed Vice President while still holding his other government positions. The Farrell-Perón duo reached the height of its power, which they would use to expel the other right-wing nationalists: Bonifacio del Carril, Francisco Ramos Mejía, Julio Lagos, Miguel Iñiguez, Juan Carlos Poggi, Celestino Genta, among others.[65]

Pressure from the United States

At the same time, the United States was increasing its pressure on Argentina to both declare war on the Axis and abandon the British-European sphere, objectives that were deeply related.

On 22 June the United States, followed by the entirety of Latin American countries, removed its Argentinian ambassador. Britain alone maintained their ambassador, rejecting America's characterization of the Argentine regime and accepting "neutralism" as a means to guarantee the supply for its population and armies. Above all, though, Britain was aware that the real aim of the United States was to displace it as the dominant economic power by imposing a pro-US government on Argentina. It was necessary for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to speak with Winston Churchill in person in order for Britain to withdraw its ambassador. US Secretary of State Cordell Hull recalls the fact in his Memoirs and recounts that Churchill ended up accepting the requirement "very much to his regret and almost with annoyance."[66]

The British argued that the United States intentionally distorted the facts by presenting Argentina as a "danger" to democracy. John Victor Perowne, head of the South American Department of the Foreign Office warned:

If Argentina can be effectively subdued, the control of the State Department over the Western Hemisphere will be complete. This will simultaneously contribute to mitigating the potential dangers of Russian and European influence on Latin America, and will separate Argentina from what is supposed to be our orbit.[67]

In August the United States froze Argentine reserves in its banks, and in September it canceled all permits to export to Argentina steel, wood and chemicals, prohibiting its ships from entering Argentine ports. Finally the United States maintained a policy of full support and militarization of Brazil, paradoxically governed then by the dictatorship of the fascist-sympathizer Getúlio Vargas.

The measures taken by the United States left Argentina isolated, but at the same time led to an intensification of its industrial and labor politics

Labor and Social Policy

In 1944, Farrell decisively imposed the labor reforms suggested by the Secretary of Labor. The government summoned labor unions and employers to negotiate through collective bargaining, a process without precedents in Argentina. 123 collective agreements affecting 1.4 million laborers and employers were signed. The following year another 347 agreements covering 2.2 million workers would be signed.

On November 18, 1944, the Field Hand Statue was announced, which modernized the quasi-feudal situation in which rural workers found themselves and alarmed the owners of the large ranches that controlled Argentine exports. On November 30, labor courts were established, which also met great resistance from employers and conservative groups.

On December 4, a retirement program for commercial employees was approved. This was followed by a union demonstration in support of Perón organized by the socialist Ángel Borlenghi, Secretary General of the union. Perón gave a public speech to the huge crowd that had gathered there, estimated to be 200,000 people.[68]

Likewise, unionization of workers continued to grow: while there were 356 unions with 444,412 members in 1941, by 1945 this number had grown to 969 unions with 528,523 members.[69]

The Farrell-Perón team, with the help of a sizeable group of unionists, was profoundly reshaping the culture of labor relations, which up until then had been characterized by the dominance of the paternalism typical of the estancias. One employer opposed to the Peronist labor reforms asserted at the time that the most serious of them was that workers "began to look their employers in the eyes".[70] In the context of this cultural transformation regarding the place of workers in society, the working class grew continuously thanks the accelerated industrialization of the country. This great socio-economic transformation was the base of the "pro-labor nationalism" that took form between the second half of 1944 and the first half of 1945 and which would assume the name of Peronism.[56]

Industrial Policy

Ramirez and above all Farrell continued an industrialization policy that was in the hands of labor. Both were leading a rapid transformation of Argentine society, prompting a growth of the working class and salaried employees due to the growing presence of women in the job market, the appearance of a large group of small and mid-sized industrial companies, and the migration to Buenos Aires of many rural workers (disparagingly known as ', with different cultural components than those characterized by the large wave of European immigrants (1850–1950) that flooded the country.

The main measures taken by the dictatorship with regard to industrial policy were:

- The creation of a Secretary of Industry with ministerial rank (Ramírez, 1943);

- The use of a tariff system;

- The nationalization of the grain elevators and the Original Gas Company.

- The governrment takeover of the Buenos Aires Transportation Company (Corporación de Transportes de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires), a symbol of corruption during the Infamous Decade with great economic importance to the region of Cuyo;

- The creation of an Industrial Credit Bank, crucial for the promotion of industry (Farrell, 1994);

- In June 1944, the prototype for the first medium tank manufactured in Argentina was presented. The tank, named "Nahuel", was designed by Lieutenant Coronel Alfredo Baisi;

- The completion of the construction works of the first blast furnace in the country

- The dissolution of the regulatory committees and the Mobilizing Institute, which were created during the Infamous Decade in order to protect corporate interests.

1945

1945 was one of the most important years in Argentine history. It began with the obvious intention of Farrell and Perón to prepare the atmosphere to declare war on Germany and Japan with the aim of exiting the state of total isolation in which the country found itself and providing a path to conduct elections.

Already in the October of the previous year the dictatorship requested a meeting with the Pan-American Union in order to consider a common course of action. Consequently, new members of the right-wing nationalist faction went on to abandon the government: the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Orlando L. Peluffo; the "interventor" of the Corrientes, David Uriburu; and above all General Sanguinetti, ousted from the crucial position of "interventor" of the Buenos Aires Province, which, after a brief interregnum, was assumed by Juan Atilio Bramuglia, the socialist lawyer of the Railway Union, combining the union faction that began the rapprochement of the labor movement and the military of Péron's group.

In February Perón undertook a secret trip to the United States in order to reach an agreement on Argentina's declaration of war, the cessation of the blockade, the recognition of the Argentine government, and Argentina's participation in the Inter-American Conference on the Problems of War and Peace to be held in Mexico City on 21 February. Shortly after the right-wing nationalist Rómulo Etcheverry Boneo resigned as Minister of Education and was replaced by Antonio J. Benítez, a member of Farrell and Perón's group.

Argentina, along with the majority of Latin-American countries, declared war on Germany and Japan on March 27. A week later Argentina signed the Chapultepec Act and was entitled to participate in the San Francisco Conference that founded the United Nations on 26 June 1945.

Concurrent with this international turn, the government initiated a corresponding domestic turn aimed at conducting elections. On January 4, the Minister of the Interior, Admiral Tessaire, announced the legalization of the Communist Party. The pro-Nazi journals "Cabildo" and "El Pampero" were banned, and university "interventors" were ordered to cease in order to return to the reformist system of university autonomy; professors who had been dismissed were reinstated. Horacio Rivarola and Josué Gollán were elected by the university community as rectors of the University of Buenos Aires and the National University of the Littoral respectively; both proceeded to dismiss in turn the teachers who joined the government.

Peronism vs. Anti-Peronism

For Argentina, the year 1945 was characterized primarily by the radicalization of the conflict between Peronism and Anti-Peronism, driven to a large extent by the United States through its Argentine ambassador Spruille Braden. Henceforth the Argentine population would be divided into two factions directly opposed to one another: a largely Peronist working class and a largely anti-Peronist middle class and upper class.

Braden arrived in Buenos Aires on 19 May. Braden was one of the owners of the mining company in Chile Braden Copper Company, an advocate of the imperialist "big stick". He openly held an anti-union position and opposed the industrialization of Argentina.[71] It had previously played a significant role in the Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay, preserving the interests of the Standard Oil[72] and operating in Cuba (1942) in order to sever relations its Spain.[73] Braden later served as United States Undersecretary of Latin American Affairs and began to work as a lobbyist paid by the United Fruit Company, promoting the 1954 coup against Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala.[74]

According to the British ambassador, Braden had "the fixed idea that he had been chosen by Providence to overthrow the Farrell-Perón regime." From the outset, Braden began to publicly organize and coordinate the opposition, exacerbating the internal conflict . On June 16, the opposition went on the offensive with the famous Trade and Industry Manifesto, in which 321 employers' organizations, led by the Argentine Stock Exchange and the Chamber of Commerce, sharply questioned the government's labor policies. The main complaint of the business sector was that "a climate of mistrust, provocation and rebelliousness is being created, which encourages resentment and a permanent spirit of hostility and vindication".[74]

The union movement, in which Perón's open support still did not predominate,[75] reacted swiftly in defense of labor policy, and on 12 July the CGT organized a multitudinous event under the motto "Against capitalist reaction." According to Perón, the radical historian Felix Luna was the first time that the workers began to identify themselves as "Peronistas".

Social and political polarization continued to escalate. Anti-Peronism adopted the banner of democracy and harshly criticized what it called anti-democratic attitudes on the part of its opponents; Peronism took up social justice as its flag and sharply criticized his adversaries' contempt for workers. In line with this polarization, the student movement expressed its opposition with the slogan "no to the dictatorship of the espadrilles", and the trade union movement responded with "espadrilles yes, books no".[76]

On September 19, 1945 the opposition appeared united for the first time with an enormous demonstration of more than 200,000 people, the March for Freedom and the Constitution, which marched from Congress to the Recoleta neighborhood in Buenos Aires. 50 eminent figures of the opposition led the march, among whom were the radicals José Tamborini and Enrique Mosca, the socialist Nicolás Repetto, the radical anti-personalist Diógenes Taboada, the conservative Laureano Landaburu, the Christian democrats Manuel Ordóñez and Rodolfo Martínez, the communist sympathizer Luis Reissig, the progressive democrat Joan José Díaz Arana, and the rector of the University of Buenos Aires Horacio Rivarola.

The historian Miguel Ángel Scenna writes about the event: The march was a spectacular demonstration of opposition power. A long and dense mass of 200,000 people - something seldom or never seen - covered the roads and sidewalks.

It has been noted that the majority of the demonstration were people from the middle- and upper-classes, a fact which is historically indisputable, but this does not invalidate the historical significance of its social breadth and political diversity. From the perspective of the present, one can claim that the demonstration consisted of one of the two sides into which society was dividing, but at the time the march appeared to unite practically all the political and social forces that had operated in Argentina.

The opposition march strongly impacted Farrell-Perón's power and triggered a succession of anti-Peronist military clashes that took place on October 8 when the Campo de Mayo military forces, led by General Eduardo Ávalos (one of the leaders of the GOU), demanded the resignation and arrest of Perón. On October 11, the United States asked Britain to stop buying Argentine goods for two weeks in order to bring down the government.108 On October 12, Perón was arrested and taken to Martín García Island, located in the Río de la Plata. The opposition leaders had the country and the government at their disposal. "Perón was a political corpse," 109 and the government, formally presided over by Farrell was actually in the hands of Avalos, who replaced Perón as Minister of War and intended to hand over power to civilians as soon as possible.

Perón's position as vice president was assumed by the Minister of Public Works, General Juan Pistarini (who continued to be Minister of Public Works in addition), and Chief Rear Admiral Héctor Vernengo Lima became the new Minister of the Navy. The tension reached a point where the radical leader Amadeo Sabattini was derided as a Nazi in the Radical House, a gigantic civil act attacked the Military Circle (October 12), and a paramilitary commando even planned to assassinate Perón.

The Radical House on Tucumán Street in Buenos Aires had become the center of the opposition's discussions. But days went by without any decision, and the opposition leaders made serious mistakes: for one, the decision not to organize and to wait passively for the Armed Forces themselves to act. Another more serious mistake was accepting and often promoting employer revanchism. October 16 was payday:

When they went to collect their two weeks' salary, workers found that they had not been paid for October 12, a holiday, despite the decree signed days earlier by Perón. Bakers and textile workers were the most affected by the bosses' reaction. "Go and complain to Perón!" Was the sarcastic answer they received.

October 17, 1945

The following day, October 17, 1945, witnessed one of the most important events in Argentine history. An unfamiliar social class, which had remained completely absent from Argentine history until then, burst into Buenos Aires and demanded Perón's freedom. The city was taken by tens of thousands of workers from the industrial areas that had been growing on the outskirts of the city. The crowd set itself up in the Plaza de Mayo. It was characterized by the large number of young people and especially women who were part of it, and by the predominance of people with hair and skin darker than those who attended the traditional political acts of the time. The anti-Peronist opposition stressed these difference, referring to them in derogatory terms such as "blacks", "fat people", " descamisados (shirtless)", "cabecitas negras". It was the Radical Unionist leader Sammartino who used the much criticized term "zoo flood".[77]

The protestors were accompanied by a whole new generation of young people and new union delegates belonging to the unions of the General Confederation of Labor, which had responded to a sugar workers' strike two days earlier. It was a completely peaceful demonstration, but the political and cultural upheaval was of such heft that, in a few hours, the triumph of the anti-Peronist movement had been cancelled out, as did the remaining power of the military government.

During that day, military commanders discussed the method of stopping the crowd. The Navy Minister, Héctor Vernengo Lima, proposed suppressing the protesters with firearms, but Ávalos objected.[78] After intense negotiations the radical Armando Antille distinguished himself as Perón's delegate; he was freed and the same night addressed his sympathizers from a balcony at the Casa Rosada. A few days later the date of the elections was established: February 24, 1946.

1946 Election

Political Forces

After October 17 both sides organized for the elections.

Peronism, with the candidacies of Juan Perón and the radical Hortensio Quijano, could not join any of the existing political parties and had to organize quickly on the basis of three new parties:

- the Labour Party organized by the trade unions and chaired by the revolutionary unionist Luis Gay;

- the Radical Civic Union Renewal Group, led by Quijano and Antille, comprised radicals who had left the Radical Civic Union;

- the Independent Party, chaired by Admiral Alberto Tessaire, comprised conservatives who supported Perón.

The three parties coordinated their actions through a National Political Coordination Group (JCP), which was chaired by railroad union lawyer Juan Atilio Bramuglia. There, it was agreed that each party would elect its candidates and that 50% of the positions would be given to the Labor Party while the remaining 50% was to be distributed in equal parts between the Radical Civic Union Renovating Group and the Independent Party.[80] The anti-Peronist united in the Democratic Union, whose candidates were the radicals José Tamborini and Enrique Mosca and which combined:

- the Radical Civic Union (UCR)

- the Socialist Party

- the Democratic Progressive Party

- the Communist Party

The conservative National Democratic Party (PDN), supported mostly by the governments of the infamous decade, was unable to join the Democratic Union due to the opposition from the Radical Civic Union. Although the PDN gave orders to vote for Tamborini-Mosca, its exclusion from the anti-Peronist alliance facilitated its fragmentation. In some cases, as in the province of Córdoba, the PDN formally joined the alliance.[81] The same year, a faction formed within the Radical Civil Union, the Intransigence and Renewal Movement, which adopted a position contrary to the Democratic Union and the radical factions that supported it (the unionists).

Smaller parties also joined the Democratic Union: the Popular Catholic Party and the Center-Independent Union, as well as important students groups, employer groups, and professional groups (the Center for Engineers, the Lawyers' Association, the Argentine Society of Writers, etc.).

The Democratic Union led unique candidates for the presidential formula but allowed each party to take its own candidates in the districts. The Radical Civic Union actually had its own candidates, but the other forces used various alternatives. Progressive and communist democrats established in the Federal Capital an alliance called Resistance and Unity that took as candidates for senators Rodolfo Ghioldi (Communist) and Julio Noble (Democratic Progressive). In Cordoba the alliance also included the conservative National Democrats. Socialists tended to submit their own candidates as well.

Campaign

Peronism, in whose marches women played an important role, proposed recognizing women's suffrage. The National Assembly of Women, chaired by Victoria Ocampa, who belonged to the Democratic Union and had long advocated for women's suffrage, opposed the initiate on the grounds that the reform should be carried out by a democratic government and not by a dictatorship. The proposal ultimately failed to pass.[82] Regardless, Perón was accompanied throughout his campaign by his wife Eva Perón, a new development in Argentine politics.

During the election campaign the government passed a law implementing a Christmas bonus (SAC) along with other improvements for workers. Employers' associations openly resisted the measure, and at the end of December 1945 not a single company had paid the SAC. In response, the General Confederation of Labour declared a general strike, which employers answered with lockouts in large retail stores. The Democratic Union, including the workers' parties that joined it (the Socialist Party and the Communist Party), supported the employers' groups, who opposed the SAC, whereas Peronism openly supported the unions in their fight to guarantee the SAC. A few days later the unions secured an important victory, which strengthened Peronism and left anti-Peronist forces descoloadas, by reaching an agreement with management over the recognition of SAC, which would be paid in two installments.[83]

Another important event that occurred during the campaign was the publication of the "Blue Book". Less than two weeks before the elections, an official initiative of the United States government, with the title "Conference of Latin-American Republics with respect to the Argentine situation", better known the "Blue Book". The initiative had been prepared by Spruille Braden and consisted of an attempt by the United States to propose internationally the military occupation of Argentina, applying the so-called Doctrine Rodriguez Larreta. Once again, both sides adopted positions fundamentally opposed to one another: the Democratic Union supported the "Blue Book" and the immediate military occupation of Argentina by US-led military forces; in addition, they demanded that Perón be disqualified by law as presidential candidate. In his turn, Perón counterattacked by publishing the "Blue and White Book" (in reference to the colors of the Argentine flag) and popularizing a slogan that established a blunt dilemma, "Braden or Perón", which had a strong influence on public opinion around election day.107

Election

In general, the political and social forces of the time anticipated a safe and widespread victory for the Democratic Union in the elections of February 1946. The newspaper "Crítica" estimated that Tamborini would win 332 voters and Perón a mere 44. In fact, Progressive Democrats and Communists had prepared a coup led by Colonel Suarez, which the Radical Civic Union considered unnecessary because they considered that the election was won.[84] That same day, shortly after the elections closed, the socialist leader Nicolás Repetto confirmed this certainty in victory while also praising the fairness with which it was achieved.[85]

Contrary to such predictions, Perón won 1,527,231 votes (55%) compared to Tamborini's 1,207,155 (45%), winning in every province except for Corrientes.[86]

On the Peronist side, the organized labor faction won 85% of the votes in the Labor Party. On the anti-Peronist side, the defeat was particularly decisive for the Socialist and Communist parties, which failed to achieve any representation in the National Congress.

See also

- Argentina in World War II

- Juan Perón

Citations

- Rock, David. Authoritarian Argentina. University of California Press, 1993.

- Palermo, Vicente (2008). Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture - "Uriburu, Jose Felix (1868-1932)". Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 206–207.

- Historia Integral Argentina, Partidos, ideologías e intereses. Buenos Aires: CEAL, pp. 88-89

- Béjar (1983): 33-36.

- Walter, Richard J. (1985). The Province of Buenos Aires and Argentine Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–118.

- Nallim, Jorge A. (2012). Transformations and Crisis of Liberalism in Argentina 1930-1955. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 10–11.

- Cattaruzza (2012): 118-119.

- Troncoso (1976), p. 20

- Gerchunoff et al., p. 159; Schvarzer, p. 190

- Milcíades Peña (1986): Industrialización y clases sociales en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: Hyspamérica, p. 16.

- Diego Dávila: «El 17 de octubre de 1945», in Historia integral argentina; El Peronismo en el poder. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina, 1976, p. 88.

- Samuel L. Baily (1985): Movimiento obrero, nacionalismo y política en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Hyspamérica, p. 90

- Baily, p. 90

- Potash (1981), p. 275

- Rodríguez Lamas, Daniel (1983). Rawson, Ramírez, Farrell. Centro Editor de América Latina. pp. 13–21.

- Romero, José Luis (2002). Las ideas políticas en Argentina. Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 250.

- Félix Luna (1975): Alvear, las luchas populares en la década del 30. Buenos Aires: Schapire, pp. 318-319; Potash (p. 274-275) relates that on 26 May 1943 Ramírez met with seven radical leaders in the house of Coronel Enrique González of the United Officers' Group.

- Potash (1981), pp. 280-2

- Ferrero (1976), p. 253

- "Buques de la Armada Argentina 1900-2006, Armada Argentina". histarmar.com.ar. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Rodríguez Lamas (1983), pp. 17-19.

- Rodríguez Lamas (1983), 65-72.

- David Kelly (1962): El poder detrás del trono, Buenos Aires: Coyoacán, p. 34

- Potash (1981), p. 277 (note 22)

- Ferrero (1976), p. 286

- García Lupo, Rogelio. "Cada vez hay más generales indígenas en Sudamérica", interview by Juan Salinas, Causa Popular, September 23, 2006

- Potash (1981), pp. 273, 276-7

- Potash (1981), p. 268

- Ferrero (1976), p. 259

- Potash (1981), pp. 275-6, 279

- Rodríguez Lamas (1983), pp. 22-24.

- Rodríguez Lamas (1983), pp. 48-49.

- Rodríguez Lamas (1983), pp. 24-25.

- Rouquié, Alain (1982). Poder militar y sociedad política en la Argentina II 1943-1973. Buenos Aires. Emecé Editores S.A. pp. 27–28. ISBN 950-04-0119-3.

- Del Campo, Hugo (2012). Sindicalismo y Peronismo. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9789876292504.

- Del Río, pp. 211-212

- Luna, Félix (1994). Breve historia de los argentinos. Buenos Aires: Planeta / Espejo de la Argentina. ISBN 950-742-415-6.

- Rodríguez Lamas (1983), pp. 32-3.

- Ferrero (1976), p. 265

- La falsa opción de los dos colonialismos, FORJA, citado por A. Jauretche en FORJA (1962), Buenos Aires : Coyoacán, pp. 102-107

- "Loja, Fabricio. El arte de la injuria y el humor en la ensayística argentina. Ramón Doll y Arturo Jauretche. Vidas paralelas. Vidas divergentes; Ponencia presentada en las Jornadas de Pensamiento Argentino, organizadas en Rosario en noviembre del 2003". dialogica.com.ar. Archived from the original on 2007-06-01. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Moret, Galo; Scavia, Juan (1944). Instrucción religiosa y cien lecciones de historia sagrada, Buenos Aires: Consejo Nacional de Educación; quoted by Ferrero (1983), p. 269

- Sentence written on school blackboards by order of Ignacio B. Olmedo, "interventor" of the National Council of Education. Source: Ferrero (1983), pp. 293-4

- "Declaración sobre democracia efectiva y solidaridad latinoamericana, 15 de octubre de 1943, Escritos y discursos del Dr. B. A. Houssay, Sitio de Bernardo Houssay". Archived from the original on 2006-05-05. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Godio, Julio (2000). Historia del movimiento obrero argentino (1870–2000), Tomo II, p. 812

- Baily, Samuel L. (1985). Movimiento obrero, nacionalismo y política en Argentina, Buenos Aires: Hyspamérica

- Matsushita, Hiroshi (1986). Movimiento obrero argentino. 1930–1945. Buenos Aires: Hyspamérica

- El término «nacionalismo laborista» fue formulado por Julio Godio, ob. cit. p. 803

- Matsushita, ob. cit., p. 258

- Baily, Samuel L. (1984). Movimiento obrero, nacionalismo y política en la Argentina, Buenos Aires: Paidós, pp. 84; López, Alfredo (1975), Historia del movimiento social y la clase obrera argentina, Buenos Aires: A. Peña Lillo, p. 401

- López, Alfredo (1975), Historia del movimiento social y la clase obrera argentina, Buenos Aires: A. Peña Lillo, p. 401

- Ferrero (1976), pp. 271-2

- Rouquié

- Matsushita, p. 279

- Ferrero (1976), p. 273

- Godio, Julio (2000). Historia del movimiento obrero argentino (1870–2000), Tomo II, p. 803

- Ferrero (1976), pp. 285-6

- Ferrero (1976), pp. 290-1

- Potash (1981), pp. 319-20, 329-31

- Potash (1981), pp. 338-9

- Rosa (1979), pp. 102-104

- Rodríguez Lamas (1986), p. 35.

- Rodríguez Lamas (1986)

- "La caída de Ramírez, El Historiador (Dir. Felipe Pigna)". elhistoriador.com.ar. Archived from the original on 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Ferrero (1976), pp. 295-6

- Ferrero (1976), p. 297

- "David Kelly, citado en Escudé, Carlos; Cisneros, Andrés (2000), La campaña del embajador Braden y la consolidación del poder de Perón, «Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas», CARI". argentina-rree.com. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Ferrero (1976), pp. 302-3

- Barsky, Osvaldo; Ferrer, Edgardo J; Yensina, Carlos A.: "Los sindicatos y el poder en el período Peronista", in Historia integral argentina; El Peronismo en el poder.- Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina, 1976, p. 257

- Robles, Alberto José (1987). Breve historia del movimiento obrero argentino 1852–1987: el rol de la unidad y protagonismo de los trabajadores, Buenos Aires:June 9

- Escudé, Carlos; Cisneros, Andrés (2000), La campaña del embajador Braden y la consolidación del poder de Perón, «Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas», CARI; Schvarzer, Jorge (1996). La industria que supimos conseguir. Una historia político-social de la industria argentina. Buenos Aires: Planeta, p. 194

- Ferrero (1976), p. 318

- Pardo Sanz, Rosa María (1995). Antifascismo en América Latina: España, Cuba y Estados Unidos durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe, vol. 6, no. 1, 1995, Universidad de Tel Aviv

- Eduardo Galeano: «Guatemala en el siglo del viento», in La Hora, Guatemala, November 8, 2002

- Hiroshi Matsushita (1986): Movimiento obrero argentino. 1930–1945. Buenos Aires: Hyspamérica, p. 289

- Alfredo López (1975): Historia del movimiento social y la clase obrera argentina. Buenos Aires: A. Peña Lillo, p. 410

- Quoted by Hugo Gambini in Historia del Peronismo.

- Ferrero (1976), p. 341

- "Génesis, apogeo y disolución del Partido Laborista". Monografias.com. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Rosa, p. 216

- "»Evita y la participación de la mujer», Pablo Vázquez, Rebanadas de Realidad, May 23 2006". rebanadasderealidad.com.ar. 2006-05-23. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Godio, II, p. 272

- Rosa, p. 225

- Rosa, p. 231

- «A 60 años del primer triunfo electoral de Perón», in La Gaceta de Tucumán, February 24, 2006.

References

- Ferrero, Roberto A. (1976). Del fraude a la soberanía popular. Buenos Aires: La Bastilla.

- Luna, Félix (1971). El 45. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana. ISBN 84-499-7474-7.

- Rouquié, Alain. Poder Militar y Sociedad Política en la Argentina - 1943/1973. Emecé. ISBN 950-04-0119-3.

- Potash, Robert A. (1981). El ejército y la política en la Argentina; 1928-1945. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana.

- Rosa, José María (1979). Historia Argentina. Orígenes de la Argentina Contemporánea. T. 13. La Soberanía (1943-1946). Buenos Aires: Oriente.

- Senkam, Leonardo (2015). "El nacionalismo y el campo liberal argentinos ante el neutralismo: 1939-1943". Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe. VI (I). (text online) consulted on May 4, 2007.

- Troncoso, Oscar A. (1976). "La revolución del 4 de junio de 1943". Historia integral argentina; El peronismo en el poder. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina.