1926 Louisiana hurricane

The 1926 Louisiana hurricane caused widespread devastation to the United States Gulf Coast, particularly in Louisiana. The third tropical cyclone and hurricane of the 1926 Atlantic hurricane season, it formed from a broad area of low pressure in the central Caribbean Sea on August 20. Moving to the northwest, the storm slowly intensified, reaching tropical storm strength on August 21 and subsequently attaining hurricane strength after passing through the Yucatán Channel. The hurricane steadily intensified as it recurved northwards in the Gulf of Mexico, before reaching peak intensity just prior to landfall near Houma, Louisiana on August 25 with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). After moving inland, the tropical cyclone moved to the west and quickly weakened, before dissipating on August 27.

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

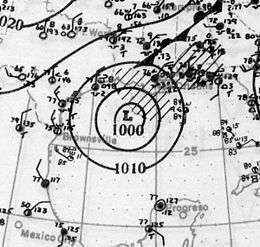

Surface weather analysis of the storm on August 25, near peak intensity | |

| Formed | August 20, 1926 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 27, 1926 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 955 mbar (hPa); 28.2 inHg |

| Fatalities | 25 |

| Damage | $6 million (1926 USD) |

| Areas affected | Cuba, Louisiana |

| Part of the 1926 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The hurricane's strong storm surge at landfall caused extensive damage to coastal regions, especially lighthouses. Strong winds caused severe infrastructural and crop damage, destroying homes and disrupting communications. Heavy rainfall, peaking at 14.5 in (370 mm) in Donaldsonville, Louisiana, also helped to damage crops. Widespread power outages also occurred in areas along the Gulf Coast. 25 deaths were reported as a result of the hurricane, with damages estimates totaling $6 million.[nb 1]

Meteorological history

A tropical depression first formed on August 20 in the central Caribbean Sea from a broad area of low pressure, based on weather reports from weather stations and ships in the vicinity.[1] Moving steadily to the west-northwest towards the western Caribbean, the disturbance slowly intensified, attaining tropical storm strength by 1200 UTC the next day.[2] Prior to the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project, however, the system was analyzed to be an open trough up until August 22.[1] The tropical storm began to move more towards the west in the Gulf of Mexico after clipping the Guanahacabibes Peninsula—the westernmost region of Cuba—late on August 22.[2]

Once in the Gulf of Mexico on August 22, the tropical storm continued to intensify, reaching hurricane strength early the next day north of the Yucatán Peninsula.[2] A ship in the hurricane's vicinity reported a barometric pressure of 994 mbar (hPa; 29.36 inHg), and other ships also reported similarly low pressures.[1] Beginning on August 24, the system began to curve northwards towards the Louisiana coast in response to a nearby cold front.[3] The hurricane continued to intensify as it moved northwards, reaching Category 2 hurricane intensity the same day and subsequently the equivalent of a Category 3 hurricane on August 25.[2] A ship reported an eye associated with the system, observing 100 mph (160 km/h) winds with a pressure of 959 mbar (hPa; 28.32 inHg) at 2100 UTC that day.[1]

The major hurricane[nb 2] intensified up until making landfall near Houma, Louisiana at 2300 UTC late on August 25, with winds estimated at 115 mph (185 km/h) and an estimated minimum barometric pressure of 955 mbar (hPa; 28.20 inHg), based on a pressure report of 959 mbar (hPa; 28.32 inHg) in Houma. Maximum sustained winds extended 23 mi (37 km) from the hurricane's center. Once over land, however, the hurricane rapidly weakened. By 1200 UTC on August 26, the system had already degenerated to a tropical storm, while still located over Louisiana near Baton Rouge. The next day, the storm weakened further to tropical depression strength as it moved towards the west, before degenerating into an open trough of low pressure near Hillsboro, Texas by 1800 UTC on August 27.[2][1]

Preparations

In preparation for the oncoming hurricane, the weather forecast office in New Orleans began to issue tropical cyclone warnings and watches and advisories for the storm on August 23. The first storm warnings were issued for areas of the United States Gulf Coast between New Orleans and Matagorda, Texas at 10:30 p.m CDT (0430 UTC) that day, indicating an approaching system with considerable intensity. As the hurricane unexpectedly recurved to the north the next day, the previously issued storm warning was shifted eastward to include areas from Morgan City, Louisiana to Galveston, Texas, while a hurricane warning was issued by the weather forecast office for areas between Morgan City and Mobile, Alabama at 10:00 p.m. CDT (0400 UTC). A storm warning was also placed for areas east of Mobile to Apalachicola, Florida. After the hurricane rapidly weakened over land, warnings and advisories from the New Orleans weather office related to the storm were discontinued by 9:00 p.m. (0500 UTC) on August 25. The warnings were communicated to potentially affected areas via mail, telegraph, and other forms of communication.[5] During the time that the hurricane was approaching the coast, the United States Weather Bureau also began experimentally transmitting surface weather analysis maps to ships by radio.[6] Small craft offshore of Mobile were recalled to the Port of Mobile, while floating dock property was removed in New Orleans.[7] Due to the potential effects of the hurricane on the cotton industry, cotton stock markets reported gains of eight to fifteen points from the first trades,[8] with stock prices closing with a net gain as high as 24 points.[9]

Impact

A storm surge of 15 ft (4.6 m) was reported in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana. At Timbalier Bay, tides were 10 ft (3 m) above average. The New Canal Light was damaged by the strong wind and waves. Previously damaged by the 1915 New Orleans hurricane, the new damage instigated a project to raise the lighthouse by 3 ft (0.9 m). The third Timbalier Bay lighthouse was also damaged by the hurricane.[10] Several small fishing schooners were lost during the storm after failing to evacuate to ports prior to the storm.[11] Upstream of the Mississippi River near Donaldsonville, Louisiana, a boat sank.[10]

Strong hurricane force winds were reported along the Louisiana coast at landfall. Grand Isle reported sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), while gusts in Thibodaux and Napoleonville were estimated at 120 mph (195 km/h).[10] Three churches, a warehouse, and ten stores were destroyed in Thibodaux. A weather station in New Orleans observed a peak wind gust of 52 mph (84 km/h). Severe damage was reported between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, which included uprooted trees and displaced barns. Roads were also blocked by debris. Window damage caused by strong winds was reported in New Orleans.[12] Baton Rouge was affected by a power outage, resulting in $20,000 in losses to the local electric company.[10] Communication wires were downed in Morgan City, preventing communication with other cities. Houses were also unroofed in the city by strong winds.[7] A ferry was also wrecked by the hurricane offshore of Morgan Point.[12] In Houma, an estimated 90% of sugar cane was lost due to the hurricane. The city's sugarhouse was also destroyed, along with an Episcopal church.[10] Three passenger trains along the Southern Pacific Railroad were detained in Avondale, Louisiana after winds were determined to be too unsafe for rail operations.[7] The strong winds and rain also caused a mail plane to crash.[13] In Tulane University, a chemistry building was destroyed by a fire during the hurricane.[13] Several other fires were reported in various areas of New Orleans.[7]

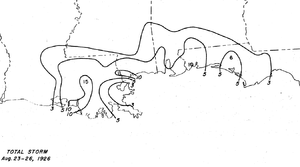

The hurricane also dropped heavy rains along the coast, which were increased by atmospheric instability in the region just prior to the storm's landfall. Rainfall peaked in Donaldsonville, Louisiana, where 14.5 in (370 mm) of rain was reported in a 24–hour period from August 25 to the 26th.[14] 24–hour rainfall records were set in 11 locations, including Donaldsonville. The rains destroyed a pecan orchard in Schriever, Louisiana, and damaged crops in Crowley, Louisiana.[10] Other rainfall amounts of at least 3 in (76 mm) were widespread across the coast. Outside of Louisiana, rainfall peaked at 10 in (250 mm) in the Florida Panhandle, with localized rainfall measurements of at least 5 in (130 mm)[14] The hurricane caused 25 deaths and an estimated $6 million in damages, of which $4 million were attributed to infrastructural damage.[15][10] After the storm, the American Red Cross sent relief to Houma, Louisiana and other affected regions to assist in rehabilitation work.[16][17]

Notes

- All damage totals are in 1926 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

- A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale.[4]

References

- Landsea, Chris; et al. "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Hurricane Research Division (August 24, 1926). "August 24 Surface Analysis" (JPG). National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Chris Landsea (June 2, 2011). "A: Basic Definitions". In Neal Dorst (ed.). Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions. Atlantic Oceanic and Meteorology Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A3) What is a super-typhoon? What is a major hurricane ? What is an intense hurricane ?. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- "New Orleans Forecast District" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 54 (8): 357–358. August 1, 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54R.357.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<357b:NOFD>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- Thomas L., Stokes (August 24, 1926). "Weather Maps to be Sent to Ships at Sea by Radio". The Evening Independent. Washington, D.C. United News. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- "Trains Are Delayed As Wind Rages". St. Petersburg Times. New Orleans, Louisiana. Associated Press. August 25, 2013. p. 1. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- "Tropical Storm Goes Northward". The Evening Independent. New Orleans, Louisiana. August 25, 1926. pp. 1, 7. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- "Cotton Moves Up on Weather News". New York Times. August 26, 1926. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. pp. 31–32. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- "A Tropical Storm Hits Gulf Coast". Nevada Daily Mail. New Orleans, Louisiana. August 26, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- "City In Darkness". The Telegraph-Herald. August 26, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- "Southern States In Path of Storm; Sweeps Louisiana". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. August 26, 1926. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- Schoner, R.W.; Molansky, S. "Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances)" (PDF). United States Weather Bureau's National Hurricane Research Project. pp. 32–33. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- "Severe Local Hail and Wind Storms, August, 1926" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 54 (8): 354–355. August 1, 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54..354.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<354:SLHAWS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- "25 Perish in Hurricane". New York Times. August 29, 1926. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- "Red Cross to Help". St. Petersburg Times. Washington, D.C. Associated Press. August 29, 1926. p. 1,7. Retrieved January 21, 2013.