1909 Grand Isle hurricane

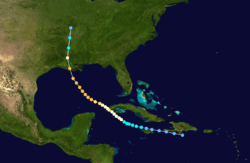

The 1909 Grand Isle hurricane was a large and deadly Category 3 hurricane that caused severe damage and killed more than 400 people throughout Cuba and the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Forming out of a tropical disturbance just south of Hispaniola on September 13, 1909, the initial depression slowly intensified as it moved west-northwest towards Jamaica. Two days later, the system attained tropical storm intensity and turned northwestward towards Cuba. On September 16, it attained the equivalent of a modern-day Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale and further strengthened to attain winds of 100 mph (155 km/h) before making landfall in Pinar del Río Province, Cuba on September 18. After a briefly weakening over land, the system regained strength over the Gulf of Mexico, with peak winds reaching 120 mph (195 km/h) the following day. After only slightly weakening, the hurricane increased in forward motion and made landfall near Grand Isle, Louisiana on September 21. The system quickly lost strength after moving over land, dissipating the following day over Missouri.

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

A collage of damage pictures in an edition of The Daily Picayune from the storm in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi | |

| Formed | September 13, 1909 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 22, 1909 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 952 mbar (hPa); 28.11 inHg |

| Fatalities | At least 400 total |

| Damage | $11 million (1909 USD) |

| Areas affected | Cuba and the United States Gulf Coast |

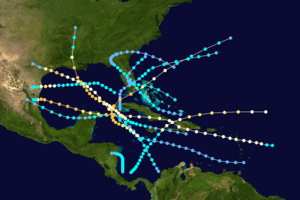

| Part of the 1909 Atlantic hurricane season | |

In the Caribbean, little impact was known to have been caused by the storm outside of Cuba where rough seas killed 29 people. In the United States, the hurricane wrought catastrophic damage across Louisiana and Mississippi. Throughout these states, 371 people are known to have been killed, making it the sixth deadliest hurricane in United States history at the time; however, it has since been surpassed by five other cyclones. Along the Louisiana coastline, a powerful storm surge penetrated 2 mi (3.2 km) inland, destroying the homes of 5,000 people. Thousands of other homes throughout the affected region lost their roofs and telegraph communication was crippled. In terms of monetary losses, the storm wrought $11 million (1909 USD; $265 million 2010 USD) in damage throughout its path.

Meteorological history

The origins of the Grand Isle hurricane were in a tropical disturbance over the western Atlantic Ocean in early September 1909. Enhanced by a strong area of high pressure over the Azores and British Isles, the system was able to gradually intensify as it neared the Lesser Antilles. On September 10, barometric pressures across several of the islands in the eastern Caribbean fell, indicating that a disturbance was moving through the region.[1] According to the Atlantic hurricane database, maintained by the National Hurricane Center, the system developed into a tropical depression south of Hispaniola in the Caribbean on September 13.[2] However, meteorologist José Fernández Partagás stated that there was no evidence of a closed circulation, a key component of tropical cyclones, until September 14.[3] Tracking west-northwestward, the depression brushed the coast of Haiti before attaining tropical storm intensity off the northwestern coast of Jamaica on September 15.[2]

After reaching this strength, the storm slowed and gradually took a more northwesterly course, heading towards Pinar del Río Province in western Cuba. On September 16, the system attained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h), what would now be considered a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale. Moving at a slow pace of 4 to 6 mph (6.4 to 9.7 km/h), the system gradually intensified. Late on September 18, the center of the storm was estimated to have made landfall in Pinar del Río Province with winds of 100 mph (155 km/h); an atmospheric pressure of 976 mbar (hPa; 28.82 inHg) was recorded during its passage.[2] The storm's eye passed over the town of Manta for four hours, between 3:00 pm and 7:00 pm on September 17.[4]

Slight weakening took place after moving over western Cuba; however, once over the Gulf of Mexico, the storm steadily regained its strength. By September 19, the system re-attained the equivalent intensity of a Category 2 hurricane and the forward motion increased. Early that morning, the storm further intensified to attain its peak winds of 120 mph (195 km/h), equivalent to a mid-range Category 3 cyclone.[2] By the afternoon of September 19, reports from the Louisiana and Mississippi coastline indicated that the outer bands of the hurricane were producing scattered rainfall.[1]

Early on September 21, it was estimated that the center of the hurricane made landfall near Grand Isle, Louisiana with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). A pressure of 952 mbar (hPa; 28.11 inHg) was recorded around this time, the lowest in relation to the storm.[2] Operational analysis of the storm indicated that it attained the equivalent intensity of a Category 4 hurricane as it made landfall.[5] The storm's lowest pressure was also operationally listed as 931 mbar (hPa; 27.49 inHg).[6] This pressure was based on operational estimates in relation to the system's storm surge and was not directly measured.[7] However, later research of the storm determined that its winds had not exceeded 120 mph (185 km/h).[2] At this time, the hurricane's radius of maximum wind was roughly 32 mi (51 km) and the overall size of the storm was estimated to be 374 mi (602 km) wide.[8] Once overland, the system quickly weakened, losing hurricane status within 12 hours and later to a tropical depression over southern Missouri.[2] The remnants of the system were last noted on September 22 as it merged with a trough over the Midwestern United States.[1]

Impact

In western Cuba, the hurricane brought strong winds and heavy rains to several areas. A maximum of 7.88 in (200 mm) of rain fell in a 24‑hour span. The strongest recorded winds reached 60 mph (95 km/h).[1] Numerous buildings in western Cuba sustained extensive damage and a large portion of the orange crop was lost. Ships were pushed onshore by the hurricane's large swells.[9] Throughout Pinar del Río Province, damage was estimated at $1 million (1909 USD).[1] Amidst rough seas produced by the hurricane, the steamship Nicholas Castina sank off the coast of Cuba, near the Isle of Pines. At least 29 people drowned in the wreck.[10] Of the fatalities, 27 were crew members and two were passengers.[11]

United States

Prior to the hurricane's arrival in the United States, the National Weather Bureau issued several hurricane warnings. As the storm passed over western Cuba, warnings were declared for much of the Gulf Coast of Florida and all ships in the Gulf or planning to set sail were advised return and remain at port.[12] Warnings were then issued for the northern Gulf Coast, allowing residents time to evacuate before the storm struck.[1]

In the United States, the storm wrought extensive damage along the Gulf Coast. At least 371 people were killed by the storm; however, this is considered a conservative estimate and the true death toll may never be known.[1] Of the known fatalities, 353 took place in Louisiana and 18 in Mississippi.[13][14][15] This makes the 1909 Grand Isle hurricane the eleventh deadliest hurricane in United States history. However, at the time of its occurrence, it was the sixth deadliest storm in the country.[16] Damage throughout Louisiana and Mississippi was estimated to be at least $10 million (1909 USD).[17]

Louisiana

In New Orleans, the storm caused substantial damage, with many homes destroyed and ships wrecked.[17] Communication with the city was completely lost after most of the telegraph wires were downed. Around 3:00 pm on September 21, advisories from the New Orleans Weather Bureau ceased, leading to concerns over the state of the city. Prior to the communication loss, the Weather Bureau reported that waves along the Mississippi River banks were surpassing 3 ft (0.91 m) and water rise in New Orleans itself could reach unprecedented levels. Several lakes overflowed their banks as water from the Mississippi River back-flowed into them, flooding nearby lowlands.[18] The resulting floods, which inundated areas with upwards of 10 ft (3.0 m) of water,[3] were similar in scale to the flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, nearly 100 years later. However, due to the lack of residential buildings in the area at the time, the flooding caused far less destruction than that of Katrina.[19] A report falsely claimed that the city's French Quarter was "swept away". A total of 306 coal barges sank off the coast of New Orleans and Lobdell (West Baton Rouge Parish), incurring over $1 million in losses.[17] Nearly every sugar cane plantation between New Orleans and Baton Rouge sustained damage, resulting in at least $1 million in losses.[20]

Strong winds from the hurricane lifted homes off their foundations and in some cases, the homes were blown away from where they originally stood. Many towns in Louisiana were isolated immediately after the storm as telegraph communication was lost. Along a 25 mi (40 km) near where the storm made landfall,[17] a 15 ft (4.6 m) storm surge destroyed the homes of 5,000 people and traveled 2 mi (3.2 km) inland.[13] At least 300 of the fatalities took place in southeastern Louisiana, the hardest hit region. Many people who were boating on the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico were caught in the storm's 80 mph (130 km/h) winds and officials presumed that all who were caught in this perished.[17] Near the Texas border, it was estimated that two-thirds of the unharvested rice crop was ruined by the hurricane.[18] In Baton Rouge alone, damage from the hurricane was estimated at $2.9 million (1909 USD).[21] Throughout Louisiana, a total of 353 people were killed by the hurricane according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.[13] A maximum of 13.5 in (340 mm) of rain fell in the state during the passage of the hurricane.[22]

Elsewhere

At least 18 fatalities also took place in Mississippi where many towns and cities were flooded.[14][15] The cities of Natchez and Greenville were mostly destroyed by the hurricane.[23] In Natchez, winds up to 50 mph (80 km/h) blew roofs off homes and shut down the local power station, leaving the city in darkness. Telegraph wires were also downed, cutting communication with the surrounding area.[18] The Biloxi Bay Bridge was swamped by large waves and it was thought that it would be destroyed by the storm at one point. Although the bridge held through the storm, one person died after being washed away while crossing it. Initial estimates stated that damage in Biloxi was between $40,000 and $50,000 (1909 USD). Along a 4 mi (6.4 km) stretch of beach in Mississippi, all of the homes and 300 ft (91 m) of the electric car line were destroyed by the hurricane's storm surge.[24] Further north in Jackson, communication in the city was lost and the dome of the newly constructed capital building was destroyed by high winds. Two people were killed in the city after being crushed by falling walls.[15] A maximum of 7.02 in (178 mm) of rain fell in Mississippi during the passage of the hurricane.[22]

In areas in and around Pensacola, Florida, 60 mph (97 km/h) winds caused some damage.[18] At the local pier, a ship, named Romanoff, toppled over onto a wharf due to large waves produced by the hurricane. Two barges carrying lumber sank near the western beach of Pensacola and several others lost their cargo. Many small ships were destroyed by large swells and according to The New York Times, some of these were "...swamped and pounded into pieces".[24] Further inland, the remnants of the hurricane brought light to moderate rainfall to portions of the central United States. A maximum of 3.2 in (81 mm) of rain fell in Arkansas; 3.35 in (85 mm) in Missouri; 2.54 in (65 mm) in Tennessee; and 2.29 in (58 mm) in Kentucky.[22] A 25 mi (40 km) section of the Louisville and Nashville railroad and an 8 mi (13 km) section of the Illinois central railroad were washed out by floods caused by the storm's remnants.[1]

Aftermath

Although the storm killed more than 370 people in the United States, the National Weather Bureau was credited for "invaluable warnings" prior to the hurricane's arrival, saving many lives.[1] Following the hurricane's landfall on September 21, rescue and relief efforts began taking place on September 22 near Houma, Louisiana.[21] By September 25, thousands of dollars worth of supplies had been sent to survivors of the storm.[25] However, more than four days after the passage of the storm, many other areas devastated by the hurricane had yet to receive aid from either the government or United States Army. Congressman Robert F. Broussard sent a telegraph to the war department requesting aid; however, he had not received a response by September 27. Initially, news reports focused on the large loss of life from the storm but, once the lack of aid was noticed, their attention shifted to the hundreds of survivors who were left homeless and in dire need of basic necessities.[26] Within days of the storm's passage, there were fears that the storm ruined the cotton crop in southern Louisiana and would cause a spike in prices. However, in a report released on October 4, 1909, it was stated that the losses were much less than previously thought and as a result, there would be no change in the cotton price.[27] According to a report in 2009, the rice and cotton crops sustained 35% and 20% losses respectively in the wake of the hurricane.[13]

In 2002, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration added the storm surge from the hurricane to the Global Tsunami Database based on newspaper reports referring to the event as a tidal wave. However, four years later, a more detailed study of possible tsunamis in the past resulted in this event being "flagged" as suspect. After further review of the news articles indicating that the wave came after the hurricane, it was determined that there was a misinterpretation of the publishing date since the article was archived by telegraph on September 22, 1909, the day after the hurricane made landfall. In light of this research, the possibility of the wave being a tsunami was denied; however, it remains in the database as a "debunked" event.[28]

See also

- 1909 Atlantic hurricane season

- List of notable tropical cyclones

- Lists of tropical cyclones

References

- General

- Partagás, José Fernández; Diaz, H. (1999). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources Part VI: 1909-1910. Climate Diagnostics Center.

- Hearn, Philip D. (2004). Hurricane Camille: monster storm of the Gulf Coast. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-655-7.

- Ahrens, C. Donald (2007). Meteorology today: an introduction to weather, climate, and the environment. Cengage Learning. ISBN 0-495-01162-2.

- Gunn, Angus M. (2008). Encyclopedia of Disasters: Environmental Catastrophes and Human Tragedies. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-34002-4.

- Specific

- "1909 Monthly Weather Review" (PDF). National Weather Bureau. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. 1909. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Hurricane Research Division (2010). "Easy-to-Read HURDAT 1851-2009". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Partagás, p. 13

- Partagás, p. 12

- Hearn, p. 75

- Ahrens, p. 420

- Hurricane Specialists Division (2006). "Detailed Re-Analysis of the 1906-1910 Hurricane Seasons". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- Hurricane Research Division (June 2009). "Continental U.S. Hurricanes: 1851 to 1925". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- Partagás, p. 11

- Staff Writer (September 18, 1909). "29 Drowned In Wreck Off Cuba". The Hartford Courant. p. 1.

- Staff Writer (September 18, 1909). "Steamer Sink; 29 Perish". Gettysburg Times. p. 2. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- Staff Writer (September 17, 1909). "Hurricane Now Central in Pinar Del Rio in Cuba". The Miami News. p. 1. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Louisiana Hurricane History" (PDF). National Weather Service. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Staff Writer (September 22, 1909). "Definite Reports From Gulf Storm". Lewiston Evening Journal. p. 10. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Staff Writer (September 22, 1909). "Gulf Hurricane Sweeping North". Lewiston Evening Journal. p. 2. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Eric S. Blake; Edward N. Rappaport; Christopher W. Landsea (April 2007). "The Deadliest, Costliest, And Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones From 1851 To 2006" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- News Special Service (September 22, 1909). "Hundreds of Lives Lost by Hurricane". Dawson Daily News. p. 5. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Staff Writer (September 21, 1909). "Gulf Storm Has Scored Heavily". Lewiston Evening Journal. p. 5. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Gunn, p. 238

- Staff Writer (September 22, 1909). "Hurricane In South Leaves Chaos In Wake". The Duluth News Tribune.

- Staff Writer (September 22, 1909). "Scores Of Lives Lost". Lewiston Evening Journal. p. 1. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Isaac M. Cline (September 1909). "Climatological Data for September 1909" (PDF). National Weather Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- News Special Service (September 22, 1909). "Hurricane In South, Towns Submerged". Dawson Daily News. p. 1. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Staff Writer (September 21, 1909). "Gulf States Swept By Ruinous Storm" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Staff Writer (September 25, 1909). "Counting Dead Has Not Ceased". The Day. p. 1. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Staff Writer (September 27, 1909). "Living Suffer More Than Dead". The Day. p. 1. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Staff Writer (October 4, 1909). "No Marked Change In Cotton Crop". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 6.

- "Tsunami or Storm Surge?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 30, 2007. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1909 Grand Isle hurricane. |