1916 Gulf Coast hurricane

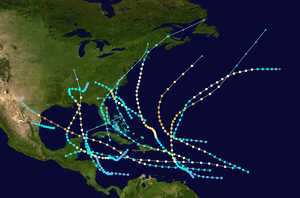

The 1916 Gulf Coast hurricane was a destructive tropical cyclone that struck the central Gulf Coast of the United States in early July 1916. It generated the highest storm surge on record in Mobile, Alabama, wrought widespread havoc on shipping, and dropped torrential rainfall exceeding 2 ft (0.6 m). The second tropical cyclone, first hurricane, and first major hurricane – Category 3 or stronger on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale – of the highly active 1916 Atlantic hurricane season,[nb 1] the system originated in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on June 28 and moved generally toward the north-northwest. Crossing the Yucatán Channel on July 3 as a strengthening hurricane and brushing Cuba with gusty winds, the cyclone reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) prior to making landfall near Pascagoula, Mississippi, at 20:00 UTC on July 5. Over land, the hurricane rapidly weakened to a tropical storm, but then retained much of its remaining strength as it meandered across interior Mississippi and Alabama for several days, its northward progress impeded by a sprawling high-pressure area to the north. The system weakened into a tropical depression on July 9 and dissipated late the next day over southern Tennessee.

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

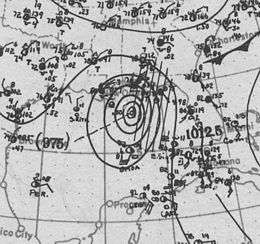

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane nearing landfall on July 5, 1916 | |

| Formed | June 28, 1916 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | July 10, 1916 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 950 mbar (hPa); 28.05 inHg |

| Fatalities | At least 34 |

| Damage | $12.5 million (1916 USD) |

| Areas affected | |

| Part of the 1916 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The United States Weather Bureau first took notice of the developing storm on July 2, issuing tropical cyclone watches and warnings for much of the central Gulf Coast on July 4 and 5. Upon moving ashore, the cyclone produced sustained Category 3 winds over coastal Mississippi and Alabama, with the worst damage mainly confined to east of the storm's center. In Mobile, an 11.6 ft (3.5 m) storm surge destroyed wharves and severely flooded the business district, while high winds unroofed or otherwise damaged many buildings. Boats of all sizes in Mobile Bay were sunk or blown ashore, and despite efforts to prepare warehouses for the tidal flooding, $500,000 in merchandise was lost.[nb 2] Farther east, Pensacola, Florida, endured several days of gale-force winds after the initial passage of the storm's core; though wind damage to homes, businesses, and trees was extensive, the worst damage resulted from storm tides along the immediate coast. Throughout the region, the hurricane severed telephone and telegraph communications. Numerous ships were lost in the Gulf of Mexico, some with their entire crews.

As the storm slowly proceeded inland, days of downpours caused rivers to rise precipitously from Mississippi to Georgia, overflowing their banks for several miles in each direction; the Chattahoochee River exceeded flood stage by 23.7 ft (7.2 m). In Alabama alone, 350,000 acres (140,000 ha) of farmland was submerged, leading to millions of dollars in crop damage. Railroads were flooded, washed out, or blocked by debris, and many sawmills and other industrial facilities were disrupted. In addition, the hurricane's outer bands spawned multiple tornadoes that each caused severe but localized damage to residential areas. Steady rainfall in western North Carolina primed the French Broad River watershed for a catastrophic flooding event when another hurricane from the Atlantic coast moved over the same area just days later. The resulting disaster, the worst in Asheville, North Carolina's history, killed 80 people. Including property damage, shipping losses, and crop failures, the hurricane cost the Gulf Coast about $12.5 million,[nb 3] and at least 34 people died in the region.[2]

Meteorological history

The second tropical cyclone of the 1916 season formed as a tropical depression in the southwestern Caribbean Sea around 12:00 UTC on June 28. The depression drifted northwestward, and on June 30 it passed just east of Cabo Gracias a Dios.[3] The system swept across the Swan Islands beginning on the morning of July 1, punctuating two days of unsettled weather there. Operationally, this was the first confirmation of the storm's existence.[4] Around 00:00 UTC on July 2, the depression intensified into a tropical storm while centered just west of the Swan Islands.[3] On the afternoon of July 3, USCGC Itasca encountered easterly gale-force winds while located 25 mi (40 km) south of Cape San Antonio, Cuba; late that night, USS Monterey also endured gales generally from the east while situated roughly 90 mi (140 km) northwest of the cape. As a result, it was determined that the system,[4] after intensifying into a hurricane at 18:00 UTC on July 3,[3] passed west of the ships through the Yucatán Channel and into the Gulf of Mexico. No further radio reports were received from ships near the hurricane, apparently because of effective shipping advisories. Upon entering the Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane began to strengthen more quickly and accelerated toward the north-northwest.[4]

As the storm approached the central Gulf Coast of the United States, it possessed maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h), making it a Category 3 major hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale.[3] This is officially listed as its peak intensity, but because observations of the storm over the open Gulf of Mexico were sparse, it may have previously been stronger. At 20:00 UTC on July 5, the hurricane made landfall near Pascagoula, Mississippi, while at its strongest known intensity.[5] At the time, this represented the earliest recorded U.S. major hurricane landfall in any season.[6] While the eye passed overhead, Pascagoula experienced a 20-minute lull in the storm's force.[7] At landfall, the radius of maximum wind was likely 17 to 23 mi (27 to 37 km) and minimum central barometric pressure was estimated at 950 hPa (28.05 inHg), the latter of which was used to derive the storm's peak winds.[5]

Moving inland, the hurricane weakened to a tropical storm by the morning of July 6, and it rapidly slowed as its northward progress was suppressed by a large high-pressure area over the Great Lakes.[8] For several days the storm meandered across Mississippi and Alabama,[5] and it continued to produce tropical storm-force winds through July 8. It finally deteriorated into a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on July 9, while centered over central Alabama. The depression persisted for nearly two more days before losing its characteristics as a tropical cyclone over southern Tennessee, late on July 10.[3] By the next morning, the disturbance had become indistinct.[9] Recent reanalysis efforts have produced multiple changes to the hurricane's track in the Atlantic hurricane database, including an earlier formation and a slower initial intensification rate.[5]

Preparations

Notice of the burgeoning hurricane was first telegraphed to United States Weather Bureau offices on July 2,[4] and advisories were disseminated to the public over the following days.[7] Late on July 4, the Weather Bureau hoisted storm warnings along the coast from Louisiana to the Florida Panhandle,[4] and the stretch between New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, was upgraded to a hurricane warning early the next day.[10] In Mobile, the advance notice of the storm was credited with saving lives and $100,000 in wares.[7] Railroads along the Gulf Coast suspended operations as the storm approached, and many small craft sought shelter in ports.[7][11] In New Orleans, women and children working in factories and department stores were sent home early on July 5 to avoid being caught in the worst conditions.[11]

Impact

As the storm passed west of Cuba, its effects extended as far east as Havana, where winds reached 56 mph (90 km/h). Across the Florida Straits, Key West, Florida, recorded 36 mph (58 km/h) winds.[4]

The strongest sustained winds measured in association with the storm were 107 mph (172 km/h) in Mobile, Alabama, corresponding to a one-minute average of 87 mph (140 km/h) adjusted for modern recording techniques. Although not directly recorded, sustained winds of Category 3 intensity probably affected coastal Mississippi and Alabama, with Category 2 winds affecting Florida.[5] Throughout the affected region, telephone and telegraph infrastructure was blown down, crippling communications.[12] The storm continued to drop flooding rains as it drifted around the Deep South for five days, resulting in significant damage to agricultural sectors of southeastern Mississippi, southern to central Alabama, and southwestern Georgia.[13][14] As waterways were at seasonably low levels prior to the tropical cyclone, the prolonged downpours caused some rivers to rise by more than 50 ft (15 m).[9] Vast fields of cotton and corn were submerged, and in areas where the cotton crop survived intact, the abundant moisture was expected to result in an outbreak of harmful boll weevils.[15] Numerous lumber companies suffered damage or interruptions to business resulting from the storm.[16]

Along the Gulf Coast of the United States, the hurricane wrought more than $1.5 million in losses to shipping, including approximately $800,000 to vessels based in Pensacola, Florida, and $750,000 in Mobile.[17] Numerous ships fell victim to the hurricane, some being lost with all crew members and passengers. Several ships went down off Ship Island, including the three-masted schooner Mary G. Dantzler, which sank with her crew of around 12.[17] The ship, owned by a Gulfport, Mississippi, lumber company, was loaded with phosphate rock when the hurricane struck.[16] The Bay St. Louis-based Champion, crewed by four, the Norwegian schooner Ancenis, worth $150,000, and an unidentified ship were also lost near Ship Island;[17][18] only the crew of the Ancenis was rescued.[18] The four-masted barquentine John W. Myers was blown aground on Ship Island and severely damaged.[17]

"Probably a score" of small vessels were wrecked or heavily damaged,[17] including the schooner Emma Harvey, which dragged anchor across the Chandeleur Islands and drifted eastward at the height of the storm. She was found floating upside-down off Pensacola on August 12, with no trace of her captain and five crewmen. After being towed into port and salvaged, the schooner survived for decades more until it was likely destroyed during Hurricane Frederic in 1979.[19] The Beulah D. was dismasted and heavily damaged, but her crew survived, and the vessel was towed into port along with the wrecked Lagoda on July 14. Another small schooner, the Cambria, was blown out to sea from Deer Island and overturned, eventually being recovered near the Dog Keys.[20] Her sole occupant was reportedly saved.[17] The total death toll from the hurricane is unknown, with estimates ranging from as low as 34[2] to "into the hundreds".[17]

Louisiana and Mississippi

Burrwood, Louisiana, near the southern end of the Mississippi River Delta, endured gale-force winds and tides 2.2 ft (0.67 m) above normal. Winds and rain were both light in New Orleans.[11]

The storm's winds damaged roughly half of the buildings in Pascagoula, Mississippi,[7] where multiple industrial facilities were destroyed. Similarly extensive damage occurred just to the north in Moss Point.[21] The storm's effects diminished to the west of Pascagoula, though significant property damage was still reported in Biloxi and Gulfport; one person was killed by the storm in the former city,[7] and a handful of homes along that stretch of coast were destroyed.[15] Property damage in Mississippi coastal towns was estimated at around $130,000,[7] and generally proved less severe than initially feared.[15] By one estimation, potentially $3 million worth of standing timber in southeastern Mississippi was destroyed,[22] though sources in Hattiesburg suggested the damage to timber locally was less severe than initially feared. In particular, it was reported that most of the trees toppled by the storm were weak and of little value. Regardless, many sawmills lost their stock or were otherwise damaged, with fires breaking out in several plants. Lumber processing companies in Laurel alone sustained around $200,000 in damage,[15] and in that town, "not more than a dozen" out of 2,400 houses in Laurel escaped the storm unscathed.[21] Greater than 5 in (130 mm) of rain fell over most of eastern Mississippi,[8] peaking at 21.53 in (547 mm) in Leakesville.[9] The entire length of the Pascagoula River in Mississippi overflowed to an average of 3 mi (4.8 km) from each bank.[9]

Alabama

As the first telegraph line out of Mobile was not restored to service until late on July 7, initial damage reports were scarce.[23] The winds unroofed or destroyed numerous buildings in the city,[14] and the storm there was accompanied by torrential precipitation arriving in two main batches; the first from the morning of July 5 to the early afternoon of July 6 dropped 8.56 in (217 mm) of rain, while an additional 4.99 in (127 mm) fell on July 7 as the storm lingered in the region.[7] The rainfall intensity peaked in the early afternoon on July 7, when 2.17 in (55 mm) of precipitation fell in just 25 minutes.[9] The heavy rainfall triggered some street flooding where rivers were obstructed by debris, and with many homes partially or fully unroofed, interior water damage was common.[7] Precipitation totals exceeded 20 in (510 mm) just east of the storm's center in parts of southern Alabama.[8]

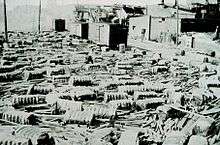

The Mobile waterfront was subjected to a storm surge of 11.6 ft (3.5 m), which still stands as the second-highest in the state's history, just short of the record set in Gulf Shores by the 1906 Mississippi hurricane, and the highest ever recorded at Mobile.[24] The tides severely flooded Mobile's business district up to four blocks inland, and it took until the late afternoon of July 6 for floodwaters to recede.[7] Some streets were submerged to a depth of up to 10 ft (3.0 m), and many residents fled to the Battle House Hotel on relatively higher ground.[25] Ultimately, waters still reached the hotel, flooding its lobby to a depth of just over 1 ft (0.30 m).[26] In advance of the storm, most wholesale merchants stacked their goods above the high water mark of the 1906 hurricane, but this proved inadequate; tides locally ran nearly 2 ft (0.6 m) higher than in 1906, ruining merchandise closest to the ground at a cost of around $500,000.[7] Many miles of railroads were covered by floodwaters and debris,[23] and the tidal action ravaged wharves.[7] At a Mobile and Ohio Railroad cargo storage shed, approximately 11,000 bales of cotton were washed away.[27]

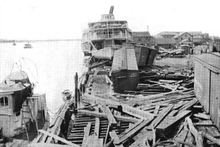

Shipping interests in Mobile Bay suffered extensively, with numerous vessels, including small boats, large yachts, schooners, and steamships, being sunk or driven aground.[7] Fifteen barges in the bay were destroyed and a similar number of sailing ships sank or sustained substantial damage.[17] In one case, a floating dry dock carrying a tugboat was deposited on the municipal docks.[28] Damage to ships was generally worsened by their owners' complacency stemming from the widespread belief that it was too early in the season for severe hurricanes.[7] In the southern part of the bay, several vessels foundered—among them the schooners Emma Lord and J. C. Smith and the barge Harry T. Morse—resulting in the deaths of about a dozen people.[7][29] Overall damage in Mobile was estimated at $2–3 million, and four drowning deaths were reported in and around the city. To the south, the storm produced severe property damage in Fort Morgan.[7]

Days of downpours in the state flooded approximately 350,000 acres (140,000 ha) of land;[9] the most prolific freshwater flooding followed the Cahaba and Alabama rivers through Perry, Dallas, Wilcox, and Monroe counties, where collectively 250,000 acres (100,000 ha) of farmlands was inundated and $2.5 million worth of crops were destroyed,[22] contributing to an estimated statewide total of $5 million in lost crops. In the same area, at least 2,000 families were forced to evacuate their homes.[21] Residents along the Coosa River faced destitution and fears of famine, resulting in a rush to slaughter cattle for food.[21] For 170 mi (270 km) of its course, the Tombigbee River flooded 1.25 mi (2.01 km) of land on both sides.[9] Multiple people drowned in floodwaters in Birmingham and Tuscaloosa,[30] and in some communities, residents clung to treetops to escape raging floodwaters. In Birmingham, the flooding closed manufacturing plants.[31] Railways and train trestles were washed out or blocked by landslides,[13] with one railroad in particular, the Southern Railway, having service interrupted on a total 140 mi (230 km) of track, mostly south and west of Birmingham.[32]

In addition to the flooding, strong winds persisted over land;[22] around Montgomery, numerous houses were destroyed by strong winds and many individuals were injured.[13] Nearby, more than 100 convicts became stranded on a prison farm after it was flooded by the Tallapoosa River.[21] While moving inland on July 6, the hurricane spawned at least four damaging tornadoes in Alabama, including one in Dallas County that leveled five small houses, injuring eight people, and toppled hundreds of trees on a plantation west of Selma. Two tornadoes in Lowndesboro and Clanton destroyed some buildings and each caused two injuries, and one in western Tallapoosa County destroyed a church and a barn.[33]

Florida

In Florida, Tampa was first to feel the storm in the form of a "slight blow".[17] Later, gusts were measured as high as 110 mph (180 km/h) in Pensacola, and average hourly winds reached 83.5 mph (134.4 km/h) for a six-hour period on July 5. At their strongest, the winds overturned automobiles and made standing impossible. As the storm slowly progressed inland, southwesterly gale-force winds continued through July 8. In addition to the exceptionally long duration, the winds were abnormally steady, not dominated by gusts as in most tropical cyclones. Numerous homes were unroofed, smokestacks toppled, and sheds torn apart, while damage to trees and other vegetation was extensive, leaving some roads impassable with debris. However, as most weaker buildings had already been demolished by the 1906 hurricane, structural damage was relatively light. Wind-inflicted property damage was estimated at $150,000.[34] A relatively modest 6.57 in (167 mm) of rain fell in Pensacola,[9] but Bonifay to the northeast recorded the storm-maximum amount of 24.5 in (620 mm), making the hurricane the wettest on record in northwestern Florida and one of the rainiest in the state as a whole.[8][35]

Along the coast, a 5 ft (1.5 m) storm surge and accompanying high waves did $850,000 in damage to shipping, wharves, and coastal structures at Pensacola.[34] The city lost electricity when the Pensacola Electric Company's engine room was flooded by the rising tide.[2] In Pensacola Harbor, two schooners carrying 70 Gulf Coast Military Academy cadets on their annual cruise were beached and severely damaged, but no passengers were harmed.[17] At a seaplane base, seven canvass seaplane hangars collapsed in the storm, and four seaplanes were battered.[17] No storm-related deaths occurred reported in Pensacola, though four lives were lost elsewhere in the state.[2]

Elsewhere

As rainfall decreased over Alabama on July 9 and 10, precipitation overspread the southern Appalachian Mountains,[9] primarily in Georgia and South Carolina.[36] At Alaga, Alabama, the Chattahoochee River (which constitutes the southern portion of the Georgia–Alabama border) rose from 3.3 ft (1.0 m) on July 5 to 43.7 ft (13.3 m) – 23.7 ft (7.2 m) above flood stage – on July 9 in response to 22.79 in (579 mm) of rainfall at that location. Other major rivers in Georgia exceeded flood stage, but generally to a lesser extent than the Chattahoochee.[9] Nonetheless, the widespread loss of crops and livestock was reported.[21] In Georgia, Decatur County bore the brunt of the flooding, with the entire tobacco crop there ruined and many bridges washed out. In neighboring Miller County, a dam at the Babcock Lumber Company plant failed, flooding the community of Babcock.[37] The flooding inflicted at least $1 million in damage in southwestern Georgia.[38] North of Cairo, a tornado cut a swath of damage 450 ft (140 m) wide on the night of July 5–6, killing a farmer and injuring his wife and son.[13] Their home was blown 150 ft (45 m) afield and then its debris strewn across a wide area. Later on July 6, another tornado in the same area destroyed two more houses. In Early County, a tornado demolished two small houses and uprooted multiple trees just south of Blakely.[33]

Heavy rainfall extended into southern Tennessee, amounting to nearly 12 in (300 mm) in Chattanooga from July 5–13.[9] Flooding on the Tennessee River left 400 people homeless in Dayton.[21] A general 3 to 6 in (75 to 150 mm) of rain fell over the French Broad River watershed of western North Carolina, causing the river to rise 4 ft (1.2 m) above flood stage at Asheville on July 11. The resulting damage to crops, homes, and industrial plants was severe,[39] costing an estimated $500,000, and although water levels quickly receded, saturated soil and swollen waterways set the stage for a catastrophic flooding event when a second hurricane moved inland from the Atlantic Coast and dropped exceptionally heavy rain over the same area on July 15 and 16. The French Broad River crested at an estimated 23.1 ft (7.0 m), 19.1 ft (5.8 m) above flood stage, contributing to the worst flood in western North Carolina's history; some 80 people died in the catastrophe and total damage reached $21 million.[40][41]

See also

- Hurricane Camille

- Hurricane Dennis

- List of Florida hurricanes (1900–49)

- List of wettest tropical cyclones in the United States

Notes

- Hurricane Four would also achieve major hurricane status later in the month, making 1916 one of only two Atlantic hurricane seasons to feature multiple major hurricanes in the month of July, the other being 2005.[1]

- Damage figures in 1916 USD values unless otherwise noted.

- Damage total compiled from sources cited throughout text.

References

- Sources

- Barnes, Jay (2013). North Carolina's Hurricane History (4th ed.). UNC Press Books. ISBN 1-4696-0833-2. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- Barnes, Jay (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5809-9. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- Bumgarner, Matthew C. (1995). "The Floods of July 1916: How the Southern Railway Organization Met an Emergency". The Overmountain Press. Southern Railway Company. ISBN 1-57072-019-3. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). Significant Tornadoes 1680–1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. Environmental Films. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- Citations

- "Hurricanes and Tropical Storms - July 2016". National Centers for Environmental Information. August 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- Barnes (2007), pp. 96–97

- Hurricane Research Division (June 16, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Frankenfield, H. C. (July 1916). "Forecasts and Warnings for July, 1916" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (7): 396–399. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..396F. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<396:FAWFJ>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Hurricane Research Division (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Barnes (2013), p. 58

- Ashenberger, Albert (July 1916). "Hurricane of July 5–6, 1916, at Mobile, Ala" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (7): 402–403. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..402A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<402:HOJAMA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Schoner, R.W.; Molansky, S. (July 1956). Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (and Other Tropical Disturbances) (PDF). National Hurricane Research Project (Report). United States Department of Commerce. pp. 12–13. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- Henry, Alfred J. (August 1916). "Floods in the East Gulf and South Atlantic States, July, 1916" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (8): 466–476. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..466H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<466:FITEGA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- "Gulf Coast will be swept by storm". Natchez Democrat. July 5, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cline, Isaac M. (July 1916). "The Tropical Hurricane of July 5, 1916, in Louisiana" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (7): 403–404. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..403C. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<403:TTHOJI>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- "Great damage and several deaths result from storm". The Tennessean. July 7, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Toll of storm, tornadoes and floods now 12 deaths". The Times. July 9, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane claims 17 lives". The Greenville News. July 7, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "No loss of life on the Mississippi coast". Jackson Daily News. July 7, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Latest News of the Lumber World". World Lumber Review. Lumber Review Company. 31 (2): 50. July 25, 1916. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Dunn, H. H. (September 1916). "Gulf Storm Damages Ships". The Marine Review. Penton Publishing Company. 46 (9): 312–313. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- "$4,000,000 damage done in two states by tropical storm and heavy rains". Franklin County Times. July 13, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bellande, Ray L. (July 1994). "The Emma Harvey: A tale of the July Storm 1916" (PDF). Ocean Springs Record. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- "Loss of brave seamen stirs the hearts of coast people". Jackson Daily News. July 15, 1916. p. 5. Retrieved May 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "South flood-stricken". Asheville Citizen-Times. July 11, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bumgarner, p. 12

- "The tropical storm passes inland today". The Concord Times. July 6, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Masters, Jeff. "U.S. Storm Surge Records". Weather Underground. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- "Million loss in Mobile". Pittsburgh Daily Post. July 8, 1916. p. 3. Retrieved May 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Water in Battle House". The Greenville Advocate. July 12, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bumgarner, p. 22

- Bumgarner, p. 17

- "100 lost in Gulf storm, is report". The Washington Times. July 8, 1916. p. 2. Retrieved May 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Death toll of storms grows in magnitude". Evening Public Ledger. July 8, 1916. p. 2. Retrieved May 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Gulf hurricane takes 9 lives". The Indianapolis Star. July 9, 1916. p. 8. Retrieved May 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bumgarner, pp. 16–17

- Grazulis, pp. 142–143

- Reed, William F. (July 1916). "Hurricane of July 5, 1916, at Pensacola, Fla" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (7): 400–402. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..400R. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<400:HOJAPF>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Flood insurance study: Holmes County, Florida and incorporated areas (PDF) (Report). Federal Emergency Management Agency. December 17, 2010. p. 4. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- "The Great Flood 1916" (PDF). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- "Crops destroyed in south Georgia". The Atlanta Constitution. July 12, 1916. p. 3. Retrieved May 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Flood waters receding; loss in Georgia is great". The Wilmington Morning Star. July 13, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved May 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Flood damage may reach half million". Greensboro Daily News. July 12, 1916. p. 3. Retrieved May 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Investigating the Great Flood of 1916". National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- Hiatt, Ashley (June 15, 2015). "NC Extremes: Flood of 1916 Wiped Out Railways, Records". State Climate Office of North Carolina. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

Further reading

- United States Coast Guard (July 18, 1916). Experiences of Tallapoosa during hurricane July 5–6, and subsequent operations (PDF) (Report). United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved May 23, 2017.