List of Dutch explorations

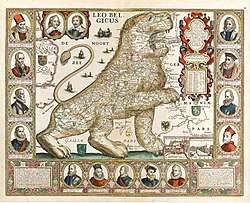

The Netherlands had a considerable part in the making of modern society.[1][2][3] The Netherlands[4] and its people have made numerous seminal contributions to the world's civilization,[5][6][7][8][9] especially in art,[10][11][12][13][14] science,[15][16][17][18] technology and engineering,[19][20][21] economics and finance,[22][23][24][25][26] cartography and geography,[27][28] exploration and navigation,[29][30] law and jurisprudence,[31] thought and philosophy,[32][33][34][35] medicine,[36] and agriculture. Dutch-speaking people, in spite of their relatively small number, have a significant history of invention, innovation, discovery and exploration. The following list is composed of objects, (largely) unknown lands, breakthrough ideas/concepts, principles, phenomena, processes, methods, techniques, styles etc., that were discovered or invented (or pioneered) by people from the Netherlands and Dutch-speaking people from the former Southern Netherlands (Zuid-Nederlanders in Dutch). Until the fall of Antwerp (1585), the Dutch and Flemish were generally seen as one people.[37]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Netherlands |

|

|

Early

|

|

Republic |

|

Topics

|

|

|

Explorations

Voyages of discovery

Orange Islands (1594)

.jpg)

During his first journey in 1594, Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz discovered the Orange Islands, at the northern extremity of Nova Zembla.

Svalbard (1596)

.jpg)

On 10 June 1596, Barentsz and Dutchman Jacob van Heemskerk discovered Bear Island,[38][39][40] a week before their discovery of Spitsbergen Island.[38][39][40]

The first undisputed discovery of the archipelago was an expedition led by the Dutch mariner Willem Barentsz, who was looking for the Northern Sea Route to China.[41] He first spotted Bjørnøya on 10 June 1596[42] and the northwestern tip of Spitsbergen on 17 June.[41] The sighting of the archipelago was included in the accounts and maps made by the expedition and Spitsbergen was quickly included by cartographers. The name Spitsbergen, meaning "pointed mountains" (from the Dutch spits – pointed, bergen – mountains), was at first applied to both the main island and the Svalbard archipelago as a whole.[38][40]

Winter surviving in the High Arctic (1596–1597)

The search for the Northern Sea Route in the 16th century led to its exploration.[43] Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz reached the west coast of Novaya Zemlya in 1594,[43] and in a subsequent expedition of 1596 rounded the Northern point and wintered on the Northeast coast.[44] Willem Barents, Jacob van Heemskerck and their crew were blocked by the pack ice in the Kara Sea and forced to winter on the east coast of Novaya Zemlya. The wintering of the shipwrecked crew in the 'Saved House' was the first successful wintering of Europeans in the High Arctic. Twelve of the 17 men managed to survive the polar winter (De Veer, 1917). Barentsz died during the expedition, and may have been buried on the northern island.[45]

Falkland Islands/Sebald Islands (1600)

In 1600 the Dutch navigator Sebald de Weert made the first undisputed sighting of the Falkland Islands. It was on his homeward leg back to the Netherlands after having left the Straits of Magellan that Sebald De Weert noticed some unnamed and uncharted islands, at least islands that did not exist on his nautical charts. There he attempted to stop and replenish but was unable to land due to harsh conditions. The islands Sebald de Weert charted were a small group off the northwest coast of the Falkland Islands and are in fact part of the Falklands. De Weert then named these islands the “Sebald de Weert Islands” and the Falklands as a whole were known as the Sebald Islands until well into the 18th century.

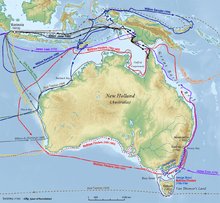

Pennefather River, Northern Australia (1606)

The Dutch ship, Duyfken, led by Willem Janszoon, made the first documented European landing in Australia in 1606.[46] Although a theory of Portuguese discovery in the 1520s exists, it lacks definitive evidence.[47][48][49] Precedence of discovery has also been claimed for China,[50] France,[51] Spain,[52] India,[53] and even Phoenicia.[54]

The Janszoon voyage of 1605–06 led to the first undisputed sighting of Australia by a European was made on 26 February 1606. Dutch vessel Duyfken, captained by Janszoon, followed the coast of New Guinea, missed Torres Strait, and explored perhaps 350 kilometres (220 mi) of western side of Cape York, in the Gulf of Carpentaria, believing the land was still part of New Guinea. The Dutch made one landing, but were promptly attacked by Maoris and subsequently abandoned further exploration.[55][56][57][58][59][60]

The first recorded European sighting of the Australian mainland, and the first recorded European landfall on the Australian continent, are attributed to the Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon. He sighted the coast of Cape York Peninsula in early 1606, and made landfall on 26 February at the Pennefather River near the modern town of Weipa on Cape York.[61] The Dutch charted the whole of the western and northern coastlines and named the island continent "New Holland" during the 17th century, but made no attempt at settlement.[61]

First charting of Manhattan, New York (1609)

The area that is now Manhattan was long inhabited by the Lenape Indians. In 1524, Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano – sailing in service of the king Francis I of France – was the first European to visit the area that would become New York City. It was not until the voyage of Henry Hudson, an Englishman who worked for the Dutch East India Company, that the area was mapped.

Hudson Valley (1609)

At the time of the arrival of the first Europeans in the 17th century, the Hudson Valley was inhabited primarily by the Algonquian-speaking Mahican and Munsee Native American people, known collectively as River Indians. The first Dutch settlement was in the 1610s at Fort Nassau, a trading post (factorij) south of modern-day Albany, that traded European goods for beaver pelts. Fort Nassau was later replaced by Fort Orange. During the rest of the 17th century, the Hudson Valley formed the heart of the New Netherland colony operations, with the New Amsterdam settlement on Manhattan serving as a post for supplies and defense of the upriver operations.

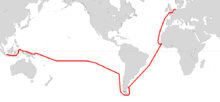

Brouwer Route (1610–1611)

The Brouwer Route was a route for sailing from the Cape of Good Hope to Java. The Route took ships south from the Cape into the Roaring Forties, then east across the Indian Ocean, before turning northwest for Java. Thus it took advantage of the strong westerly winds for which the Roaring Forties are named, greatly increasing travel speed. It was devised by Dutch sea explorer Hendrik Brouwer in 1611, and found to halve the duration of the journey from Europe to Java, compared to the previous Arab and Portuguese monsoon route, which involved following the coast of East Africa northwards, sailing through the Mozambique Channel and then across the Indian Ocean, sometimes via India. The Brouwer Route played a major role in the discovery of the west coast of Australia.

Jan Mayen Island (1614)

After unconfirmed reports of Dutch discovery as early as 1611, the island was named after Dutchman Jan Jacobszoon May van Schellinkhout, who visited the island in July 1614. As locations of these islands were kept secret by the whalers, Jan Mayen got its current name only in 1620.[62]

Hell Gate, Long Island Sound, Connecticut River and Fisher's Island (1614)

The name "Hell Gate" is a corruption of Dutch phrase Hellegat, which could mean either "hell's hole" or "bright gate/passage". It was originally applied to the entirety of the East River. The strait was described in the journals of Dutch explorer Adriaen Block, who is the first European known to have navigated the strait, during his 1614 voyage aboard the Onrust.

The first European to record the existence of Long Island Sound and the Connecticut River was Dutch explorer Adriaen Block, who entered it from the East River in 1614.

Fishers Island was called Munnawtawkit by the Native American Pequot nation. Block named it Visher's Island in 1614, after one of his companions. For the next 25 years, it remained a wilderness, visited occasionally by Dutch traders.

Staten Island (Argentina), Cape Horn, Tonga, Hoorn Islands (1615)

On 25 December 1615, Dutch explorers Jacob le Maire and Willem Schouten aboard the Eendracht, discovered Staten Island, close to Cape Horn.

On 29 January 1616, they sighted land they called Cape Horn, after the city of Hoorn. Aboard the Eendracht was the crew of the recently wrecked ship called Hoorn.

They discovered Tonga on 21 April 1616 and the Hoorn Islands on 28 April 1616.

They discovered New Ireland around May–July 1616.

They discovered the Schouten Islands (also known as Biak Islands or Geelvink Islands) on 24 July 1616.

The Schouten Islands (also known as Eastern Schouten Islands or Le Maire Islands) of Papua New Guinea, were named after Schouten, who visited them in 1616.

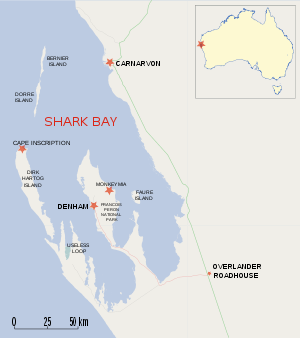

Dirk Hartog Island (1616)

Hendrik Brouwer's discovery that sailing east from the Cape of Good Hope until land was sighted, and then sailing north along the west coast of Australia was a much quicker route than around the coast of the Indian Ocean made Dutch landfalls on the west coast inevitable. The first such landfall was in 1616, when Dirk Hartog landed at Cape Inscription on what is now known as Dirk Hartog Island, off the coast of Western Australia, and left behind an inscription on a pewter plate. In 1697 the Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh landed on the island and discovered Hartog's plate. He replaced it with one of his own, which included a copy of Hartog's inscription, and took the original plate home to Amsterdam, where it is still kept in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Houtman Abrolhos (1619)

The first sighting of the Houtman Abrolhos by Europeans was by Dutch VOC ships Dordrecht and Amsterdam in 1619, three years after Hartog made the first authenticated sighting of what is now Western Australia, 13 years after the first authenticated voyage to Australia, that of the Duyfke in 1606. Discovery of the islands was credited to Frederick de Houtman, Captain-General of the Dordrecht, as it was Houtman who later wrote of the discovery in a letter to Company directors.

Carstensz Glacier, Carstensz Pyramid/Puncak Jaya (1623)

The first person to spot Carstensz Pyramid (or Puncak Jaya) is reported to be the Dutch navigator and explorer Jan Carstensz in 1623, for whom the mountain is named. Carstensz was the first (non-native) to sight the glaciers on the peak of the mountain on a rare clear day. The sighting went unverified for over two centuries, and Carstensz was ridiculed in Europe when he said he had seen snow and glaciers near the equator. The snowfield of Puncak Jaya was reached as early as 1909 by a Dutch explorer, Hendrik Albert Lorentz with six of his indigenous Dayak Kenyah porters recruited from the Apo Kayan in Borneo. The now highest Carstensz Pyramid summit was not climbed until 1962, by an expedition led by the Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer with three other expedition members – the New Zealand mountaineer Philip Temple, the Australian rock climber Russell Kippax, and the Dutch patrol officer Albertus (Bert) Huizenga.

Gulf of Carpentaria (Northern Australia) (1623)

The first known European explorer to visit the region was Dutch Willem Janszoon (also known as Willem Jansz) on his 1605–06 voyage. His fellow countryman, Jan Carstenszoon (also known as Jan Carstensz), visited in 1623 and named the gulf in honour of Pieter de Carpentier, at that time the Governor-General of Dutch East Indies. Abel Tasman explored the coast in 1644.

Staaten River (Cape York Peninsula, Northern Australia) (1623)

The Staaten River is a river in the Cape York Peninsula, Australia that rises more than 200 kilometres (120 mi) to the west of Cairns and empties into the Gulf of Carpentaria. The river was first named by Carstenszoon in 1623.

Arnhem Land and Groote Eylandt (Gulf of Carpentaria, Northern Australia) (1623)

In 1623 Dutch East India Company captain Willem van Colster sailed into the Gulf of Carpentaria. Cape Arnhem is named after his ship, the Arnhem, which itself was named after the city of Arnhem.

Groote Eylandt was first sighted the Arnhem. Only in 1644, when Abel Tasman arrived, was the island given a European name, Dutch for "Large Island" in an archaic spelling. The modern Dutch spelling is Groot Eiland.

Hermite Islands (1624)

In February 1624, Dutch admiral Jacques l'Hermite discovered the Hermite Islands at Cape Horn.

Southern Australia coast (1627)

In 1627, Dutch explorers François Thijssen and Pieter Nuyts discovered the south coast of Australia and charted about 1,800 kilometres (1,100 mi) of it between Cape Leeuwin and the Nuyts Archipelago.[63][64] François Thijssen, captain of the ship 't Gulden Zeepaert (The Golden Seahorse), sailed to the east as far as Ceduna in South Australia. The first known ship to have visited the area is the Leeuwin ("Lioness"), a Dutch vessel that charted some of the nearby coastline in 1622. The log of the Leeuwin has been lost, so very little is known of the voyage. However, the land discovered by the Leeuwin was recorded on a 1627 map by Hessel Gerritsz: Caert van't Landt van d'Eendracht ("Chart of the Land of Eendracht"), which appears to show the coast between present-day Hamelin Bay and Point D’Entrecasteaux. Part of Thijssen's map shows the islands St Francis and St Peter, now known collectively with their respective groups as the Nuyts Archipelago. Thijssen's observations were included as soon as 1628 by the VOC cartographer Hessel Gerritsz in a chart of the Indies and New Holland. This voyage defined most of the southern coast of Australia and discouraged the notion that "New Holland", as it was then known, was linked to Antarctica.

St Francis Island (originally in Dutch: Eyland St. François) is an island on the south coast of South Australia near Ceduna. It is now part of the Nuyts Archipelago Wilderness Protection Area. It was one of the first parts of South Australia to be discovered and named by Europeans, along with St Peter Island. Thijssen named it after his patron saint, St. Francis.

St Peter Island is an island on the south coast of South Australia near Ceduna to the south of Denial Bay. It is the second largest island in South Australia at about 13 km long. It was named in 1627 by Thijssen after Pieter Nuyts' patron saint.

Western Australia (1629)

The Weibbe Hayes Stone Fort, remnants of improvised defensive walls and stone shelters built by Wiebbe Hayes and his men on the West Wallabi Island, are Australia's oldest known European structures, more than 150 years before expeditions to the Australian continent by James Cook and Arthur Phillip.

Tasmania and the surrounding islands (1642)

In 1642, Abel Tasman sailed from Mauritius and on 24 November, sighted Tasmania. He named Tasmania Van Diemen's Land, after Anthony van Diemen, the Dutch East India Company's Governor General, who had commissioned his voyage.[65][66][67] It was officially renamed Tasmania in honour of its first European discoverer on 1 January 1856.[68]

Maatsuyker Islands, a group of small islands that are the southernmost point of the Australian continent. were discovered and named by Tasman in 1642 after a Dutch official. The main islands of the group are De Witt Island (354 m), Maatsuyker Island (296 m), Flat Witch Island, Flat Top Island, Round Top Island, Walker Island, Needle Rocks and Mewstone.

Maria Island was discovered and named in 1642 by Tasman after Maria van Diemen (née van Aelst), wife of Anthony. The island was known as Maria's Isle in the early 19th century.

Tasman's journal entry for 29 November 1642 records that he observed a rock which was similar to a rock named Pedra Branca off China, presumably referring to the Pedra Branca in the South China Sea.

Schouten Island is a 28 square kilometres (11 sq mi) island in eastern Tasmania, Australia. It lies 1.6 kilometres south of Freycinet Peninsula and is a part of Freycinet National Park. In 1642, while surveying the south-west coast of Tasmania, Tasman named the island after Joost Schouten, a member of the Council of the Dutch East India Company.

Tasman also reached Storm Bay, a large bay in the south-east of Tasmania, Australia. It is the entrance to the Derwent River estuary and the port of Hobart, the capital city of Tasmania. It is bordered by Bruny Island to the west and the Tasman Peninsula to the east.

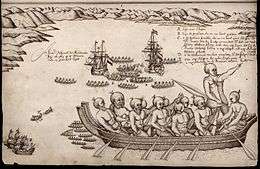

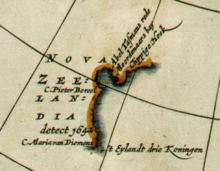

New Zealand and Fiji (1642)

In 1642, the first Europeans known to reach New Zealand were the crew of Dutch explorer Abel Tasman who arrived in his ships Heemskerck and Zeehaen. Tasman anchored at the northern end of the South Island in Golden Bay (he named it Murderers' Bay) in December 1642 and sailed northward to Tonga following a clash with local Māori. Tasman sketched sections of the two main islands' west coasts. Tasman called them Staten Landt, after the States General of the Netherlands, and that name appeared on his first maps of the country. In 1645 Dutch cartographers changed the name to Nova Zeelandia in Latin, from Nieuw Zeeland, after the Dutch province of Zeeland. It was subsequently Anglicised as New Zealand by British naval captain James Cook

Various claims have been made that New Zealand was reached by other non-Polynesian voyagers before Tasman, but these are not widely accepted. Peter Trickett, for example, argues in Beyond Capricorn that the Portuguese explorer Cristóvão de Mendonça reached New Zealand in the 1520s, and the Tamil bell[69] discovered by missionary William Colenso has given rise to a number of theories,[53] [70] but historians generally believe the bell 'is not in itself proof of early Tamil contact with New Zealand'.[71][72][73]

In 1643, still during the same expedition, Tasman discovered Fiji.

Tongatapu and Haʻapai (Tonga) (1643)

Tasman discovered Tongatapu and Haʻapai in 1643 commanding two ships, the Heemskerck and the Zeehaen commissioned by the Dutch East India Company. The expedition's goals were to chart the unknown southern and eastern seas and to find a possible passage through the South Pacific and Indian Ocean providing a faster route to Chile.

Sakhalin (Cape Patience) (1643)

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643.

Kuril Islands (1643)

In the summer of 1643, the Castricum, under command of Martin Gerritz de Vries sailed by the southern Kuril Islands, visiting Kunashir, Iturup and Urup, which they named "Company Island" and claimed for the Netherlands.

Vries Strait or Miyabe Line is a strait between two main islands of the Kurils. It is located between the northeastern end of the island of Iturup and the southwestern headland of Urup Island, connecting the Sea of Okhotsk on the west with the Pacific Ocean on the east. The strait is named after de Vries, the first recorded European to explore the area.

The Gulf of Patience is a large body of water off the southeastern coast of Sakhalin, Russia, between the main body of Sakhalin Island in the west and Cape Patience in the east. It is part of the Sea of Okhotsk. The first Europeans to visit the bay sailed on Castricum. They named the gulf in memory of the fog that had to clear for them to continue their expedition.

Rottnest Island and Swan River (1696)

The first Europeans known to land on the Rottnest Island were 13 Dutch sailors including Abraham Leeman from the Waeckende Boey who landed near Bathurst Point on 19 March 1658 while their ship was nearby. The ship had sailed from Batavia in search of survivors of the missing Vergulde Draeck which was later found wrecked 80 kilometres (50 mi) north near present-day Ledge Point. The island was given the name "Rotte nest" (meaning "rat nest" in the 17th century Dutch language) by Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh who spent six days exploring the island from 29 December 1696, mistaking the quokkas for giant rats. De Vlamingh led a fleet of three ships, De Geelvink, De Nijptang and Weseltje and anchored on the northern side of the island, near The Basin.

On 10 January 1697, de Vlamingh ventured up the Swan River. He and his crew are believed to have been the first Europeans to do so. He named the Swan River (Zwaanenrivier in Dutch) after the large numbers of black swans that he observed there.

Easter Island and Samoa (1722)

On Easter Sunday, 5 April 1722, Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen discovered Easter Island. Easter Island is one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world.[74] The nearest inhabited land (50 residents) is Pitcairn Island 2,075 kilometres (1,289 mi) away, the nearest town with a population over 500 is Rikitea on island Mangareva 2,606 km (1,619 mi) away, and the nearest continental point lies in central Chile, 3,512 kilometres (2,182 mi) away.

The name "Easter Island" was given by the island's first recorded European visitor, the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen, who encountered it on Easter Sunday (5 April[75]) 1722, while searching for Davis or David's island. Roggeveen named it Paasch-Eyland (18th century Dutch for "Easter Island").[76] The island's official Spanish name, Isla de Pascua, also means "Easter Island".

On 13 June Roggeveen discovered the islands of Samoa.

Orange River (1779)

The Orange River was named by Colonel Robert Gordon, commander of the Dutch East India Company garrison at Cape Town, on a trip to the interior in 1779.

Scientific explorations

First systematic mapping of southern celestial hemisphere (1595–1597)

In 1595, Petrus Plancius, a key promoter to the East Indies expeditions, asked Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser, the chief pilot on the Hollandia, to make observations to fill in the blank area around the south celestial pole on European maps of the southern sky. Plancius had instructed Keyser to map the skies in the southern hemisphere, which were largely uncharted at the time. Keyser died in Java the following year but his catalogue of 135 stars, probably measured up with the help of explorer-colleague Frederick de Houtman, was delivered to Plancius, and then those stars were arranged into 12 new southern constellations, letting them be inscribed on a 35-cm celestial globe that was prepared in late 1597 (or early 1598). This globe was produced in collaboration with the Amsterdam cartographer Jodocus Hondius.

Plancius's constellations (mostly referring to animals and subjects described in natural history books and travellers' journals of his day) are Apis the Bee (later changed to Musca by Lacaille), Apus the Bird of Paradise, Chamaeleon, Dorado the Goldfish (or Swordfish), Grus the Crane, Hydrus the Small Water Snake, Indus the Indian, Pavo the Peacock, Phoenix, Triangulum Australe the Southern Triangle, Tucana the Toucan, and Volans the Flying Fish. The acceptance of these new constellations was assured when Johann Bayer, a German astronomer, included them in his Uranometria of 1603, the leading star atlas of its day. These 12 southern constellations are still recognized today by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).[77][78][79][80][81][82][83]

First major scientific expedition to Brazil (1637–1644)

Within the thirty-year period the Dutch West India Company controlled the northeast region of Brazil (1624–1654), the seven-year governorship of Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen was marked by an intense ethnographic exploration.[84][85][86] To that end, Johan Maurits brought from Europe with him a team of artists and scientists who lived in Recife between 1637 and 1644: painter Albert Eckhout (specializing in the human figure), painter Frans Post (landscape painter), natural historian Georg Marcgraf (who also produced drawings and prints), and the physician Willem Piso. Together with Georg Marcgraf, and originally published by Joannes de Laet, Piso wrote the Historia Naturalis Brasiliae (1648), an important early western insight into Brazilian flora and fauna, also is the first scientific book about Brazil. Albert Eckhout, along with the landscape artist Frans Post, was one of two formally trained painters charged with recording the complexity of the local scene. The seven years Eckhout spent in Brazil constitute an invaluable contribution to the understanding of the European colonization of the New World. During his stay he created hundreds of oil sketches – mostly from life – of the local flora, fauna and people. These paintings by Eckhout and the landscapes by Post were among the Europeans' first, introductions to South America.

First ethnographic descriptions of New Netherland and North American Indians (1641–1653)

In 1641, Kiliaen van Rensselaer, the director of the Dutch West India Company, hired Adriaen van der Donck (1620–1655) to be his lawyer for his large, semi-independent estate, Rensselaerswijck, in New Netherland. Until 1645, van der Donck lived in the Upper Hudson River Valley, near Fort Orange (later Albany), where he learned about the Company's fur trade, the Mohawk and Mahican Indians who traded with Dutch, the agriculturist settlers, and the area's plants and animals. In 1649, after a serious disagreement with the new governor, Peter Stuyvesant, he returned to the Dutch Republic to petition Dutch government. In 1653, still in the Netherlands waiting for the government to decide his case, Adriaen van der Donck wrote a comprehensive description of the New Netherland's geography and native peoples based on material in his earlier Remonstrance. The book, Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant or A Description of New Netherland later published in 1655. This new book was well-crafted to the interests of his audience, consisting of an extensive description of American Indians and their customs, reports on the abundance of the area's agriculture and wealth of its natural resources.[87][88][89][90][91]

Others

First non-Asian first-hand account of Korea (1653–1666)

Jan Weltevree (1595-?) is regarded as the first naturalized Westerner to Korea. Weltevree was a Dutch sailor who arrived on the shores of an island off Joseon’s west coast in 1627 in a shipwreck. The Joseon Dynasty at that time maintained an isolation policy, so the captured foreigner could not leave the country. Weltevree took the name Bak Yeon (also Pak Yeon). He became an important government official and aided King Hyojong with his keen knowledge of modern weaponry. His adventures were recorded in the report by Dutch East India Company accountant Hendrik Hamel.[92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100]

Dutch seafarer and VOC's bookkeeper Hendrick Hamel was the first westerner to experience first-hand and write about Korea in Joseon era (1392–1897). In 1653, Hamel and his men were shipwrecked on Jeju island, and they remained captives in Korea for more than a decade. The Joseon dynasty was often referred to as the "Hermit Kingdom" for its harsh isolationism and closed borders. The shipwrecked Dutchmen were given some freedom of movement, but were forbidden to leave the country. After thirteen years (1653–1666), Hamel and seven of his crewmates managed to escape to the VOC trading mission at Dejima (an artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki, Japan), and from there to the Netherlands. In 1666, three different publishers published his report (Journal van de Ongeluckige Voyage van 't Jacht de Sperwer or An account of the shipwreck of a Dutch vessel on the coast of the isle of Quelpaert together with the description of the kingdom of Corea), describing their improbable adventure and giving the first detailed and accurate description of Korea to the western world.[94][96][97][101][102][103]

References

- Motley, John Lothrop (1855). "The Rise of the Dutch Republic", Volume I, Preface. "The rise of the Dutch Republic must ever be regarded as one of the leading events of modern times. Without the birth of this great commonwealth, the various historical phenomena of the sixteenth and following centuries must have either not existed, or have presented themselves under essential modifications."

- Rybczynski, Witold (1987). Home: A Short History of an Idea. According to Witold Rybczynski’s Home: A Short History of an Idea, private spaces in households are a Dutch seventeenth-century invention, despite their commonplace nature today. He has argued that home as we now know it came from the Dutch canal house of the seventeenth century. That, he said, was the first time that people identified living quarters as being precisely the residence of a man, a woman and their children. "The feminization of the home in seventeenth century Holland was one of the most important events in the evolution of the domestic interior." This evolution took place in part due to Dutch law being "explicit on contractual arrangements and on the civil rights of servants". And, "for the first time, the person who was in intimate contact with housework was also in a position to influence the arrangement and disposition of the house."

Rybczynski (2007) discusses why we live in houses in the first place: "To understand why we live in houses, it is necessary to go back several hundred years to Europe. Rural people have always lived in houses, but the typical medieval town dwelling, which combined living space and workplace, was occupied by a mixture of extended families, servants, and employees. This changed in seventeenth-century Holland. The Netherlands was Europe’s first republic, and the world’s first middle-class nation. Prosperity allowed extensive home ownership, republicanism discouraged the widespread use of servants, a love of children promoted the nuclear family, and Calvinism encouraged thrift and other domestic virtues. These circumstances, coupled with a particular affection for the private family home, brought about a cultural revolution... The idea of urban houses spread to the British Isles thanks to England's strong commercial and cultural links with the Netherlands." - Tabor, Philip (2005). "Striking Home: The Telematic Assault on Identity". Published in Jonathan Hill, editor, Occupying Architecture: Between the Architect and the User. Philip Tabor states the contribution of 17th century Dutch houses as the foundation of houses today: "As far as the idea of the home is concerned, the home of the home is the Netherlands. This idea's crystallization might be dated to the first three-quarters of the seventeenth century, when the Dutch Netherlands amassed the unprecedented and unrivalled accumulation of capital, and emptied their purses into domestic space."

According to Jonathan Hill (Immaterial Architecture, 2006), compared to the large scaled houses in England and the Renaissance, the 17th Century Dutch house was smaller, and was only inhabited by up to four to five members. This was due to their embracing "self-reliance", in contrast to the dependence on servants, and a design for a lifestyle centered on the family. It was important for the Dutch to separate work from domesticity, as the home became an escape and a place of comfort. This way of living and the home has been noted as highly similar to the contemporary family and their dwellings. House layouts also incorporated the idea of the corridor as well as the importance of function and privacy. By the end of the 17th Century, the house layout was soon transformed to become employment-free, enforcing these ideas for the future. This came in favour for the industrial revolution, gaining large-scale factory production and workers. The house layout of the Dutch and its functions are still relevant today. - including the Dutch-speaking Southern Netherlands prior to 1585

- Taylor, Peter J. (2002). Dutch Hegemony and Contemporary Globalization. "The Dutch developed a social formula, which we have come to call modern capitalism, that proved to be transferable and ultimately deadly to all other social formulations."

- Dunthorne, Hugh (2004). The Dutch Republic: That mother nation of liberty, in The Enlightenment World, M. Fitzpatrick, P. Jones, C. Knellwolf and I. McCalman eds. London: Routledge, p. 87–103

- Kuznicki, Jason (2008). "Dutch Republic". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 130–31. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n83. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

Although today we can easily find much to criticize about the Dutch Republic, it remains a crucial early experiment in toleration, limited government, and commercial capitalism... Dutch shipping, banking, commerce, and credit raised living standards for the rich and the poor alike and for the first time created that characteristically modern social phenomenon, a middle class... Libertarians value the Dutch Republic as a historical phenomenon not because it represented any sort of perfection, but above all because it demonstrated to several generations of intellectuals the practicality of allowing citizens greater liberties than were customarily accorded them, which in turn contributed to producing what we now know as classical liberalism.

- Raico, Ralph (23 August 2010). "The Rise, Fall, and Renaissance of Classical Liberalism". Mises Daily. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

As the modern age began, rulers started to shake free of age-old customary constraints on their power. Royal absolutism became the main tendency of the time. The kings of Europe raised a novel claim: they declared that they were appointed by God to be the fountainhead of all life and activity in society. Accordingly, they sought to direct religion, culture, politics, and, especially, the economic life of the people. To support their burgeoning bureaucracies and constant wars, the rulers required ever-increasing quantities of taxes, which they tried to squeeze out of their subjects in ways that were contrary to precedent and custom.

The first people to revolt against this system were the Dutch. After a struggle that lasted for decades, they won their independence from Spain and proceeded to set up a unique polity. The United Provinces, as the radically decentralized state was called, had no king and little power at the federal level. Making money was the passion of these busy manufacturers and traders; they had no time for hunting heretics or suppressing new ideas. Thus de facto religious toleration and a wide-ranging freedom of the press came to prevail. Devoted to industry and trade, the Dutch established a legal system based solidly on the rule of law and the sanctity of property and contract. Taxes were low, and everyone worked. The Dutch "economic miracle" was the wonder of the age. Thoughtful observers throughout Europe noted the Dutch success with great interest. - Shorto, Russell. "Amsterdam: A History of the World's Most Liberal City (overview)". russellshorto.com. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

Liberalism has many meanings, but in its classical sense it is a philosophy based on individual freedom. History has long taught that our modern sensibility comes from the eighteenth century Enlightenment. In recent decades, historians have seen the Dutch Enlightenment of the seventeenth century as the root of the wider Enlightenment.

- Molyneux, John (14 February 2004). "Rembrandt and revolution: Revolt that shaped a new kind of art". Socialist Worker. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- The Dutch Republic was the birthplace of the first modern art market, successfully combining art and commerce together as we would recognise it today. Until the 17th century, commissioning works of art was largely the preserve of the church, monarchs and aristocrats. The emergence of a powerful and wealthy middle class in Holland, though, produced a radical change in patronage as the new Dutch bourgeoisie bought art. For the first time, the direction of art was shaped by relatively broadly-based demand rather than religious dogma or royal whim, and the result was the birth of a large-scale open (free) art market which today's dealers and collectors would find familiar.

- Jaffé, H. L. C. (1986). De Stijl 1917–1931: The Dutch Contribution to Modern Art

- Muller, Sheila D. (1997). Dutch Art: An Encyclopedia

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew (4 April 2013). "Interview: Andrew Graham-Dixon (Andrew Graham-Dixon talks about his new series The High Art of the Low Countries)". BBC Arts & Culture. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Struik, Dirk J. (1981). The Land of Stevin and Huygens: A Sketch of Science and Technology in the Dutch Republic during the Golden Century (Studies in the History of Modern Science)

- Porter, Roy; Teich, Mikulas (1992). The Scientific Revolution in National Context

- Van Berkel, Klaas; Van Helden, Albert; Palm, Lodewijk (1998). A History of Science in the Netherlands: Survey, Themes and Reference

- Jorink, Eric (2010). Reading the Book of Nature in the Dutch Golden Age, 1575–1715

- Haven, Kendall (2005). 100 Greatest Science Inventions of All Time

- Davids, Karel (2008). The Rise and Decline of Dutch Technological Leadership. Technology, Economy and Culture in the Netherlands, 1350–1800 (2 vols)

- Curley, Robert (2009). The Britannica Guide to Inventions That Changed the Modern World

- During their Golden Age, the Dutch were responsible for three major institutional innovations in economic and financial history. The first major innovation was the foundation of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the world's first publicly traded company, in 1602. As the first listed company (the first company to be ever listed on an official stock exchange), the VOC was the first company to actually issue stock and bonds to the general public. Considered by many experts to be the world's first truly (modern) multinational corporation, the VOC was also the first permanently organized limited-liability joint-stock company, with a permanent capital base. The Dutch merchants were the pioneers in laying the basis for modern corporate governance. The VOC is often considered as the precursor of modern corporations, if not the first truly modern corporation. It was the VOC that invented the idea of investing in the company rather than in a specific venture governed by the company. With its pioneering features such as corporate identity (first globally-recognized corporate logo), entrepreneurial spirit, legal personhood, transnational (multinational) operational structure, high stable profitability, permanent capital (fixed capital stock), freely transferable shares and tradable securities, separation of ownership and management, and limited liability for both shareholders and managers, the VOC is generally considered a major institutional breakthrough and the model for the large-scale business enterprises that now dominate the global economy.

The second major innovation was the creation of the world's first fully functioning financial market, with the birth of a fully fledged capital market. The Dutch were also the first to effectively use a fully-fledged capital market (including the bond market and the stock market) to finance companies (such as the VOC and the WIC). It was in seventeenth-century Amsterdam that the global securities market began to take on its modern form. In 1602 the Dutch East India Company (VOC) established an exchange in Amsterdam where VOC stock and bonds could be traded in a secondary market. The VOC undertook the world's first recorded IPO in the same year. The Amsterdam Stock Exchange (Amsterdamsche Beurs in Dutch) was also the world's first fully-fledged stock exchange. While the Italian city-states produced the first transferable government bonds, they didn't develop the other ingredient necessary to produce a fully fledged capital market: corporate shareholders. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) became the first company to offer shares of stock. The dividend averaged around 18% of capital over the course of the company's 200-year existence. Dutch investors were the first to trade their shares at a regular stock exchange. The buying and selling of these shares of stock in the VOC became the basis of the first stock market. It was in the Dutch Republic that the early techniques of stock-market manipulation were developed. The Dutch pioneered stock futures, stock options, short selling, bear raids, debt-equity swaps, and other speculative instruments. Amsterdam businessman Joseph de la Vega's Confusion of Confusions (1688) was the earliest book about stock trading.

The third major innovation was the establishment of the Bank of Amsterdam (Amsterdamsche Wisselbank in Dutch) in 1609, which led to the introduction of the concept of bank money. The Bank of Amsterdam was arguably the world's first central bank. The Wisselbank's innovations helped lay the foundations for the birth and development of the central banking system that now plays a vital role in the world's economy. It occupied a central position in the financial world of its day, providing an effective, efficient and trusted system for national and international payments, and introduced the first ever international reserve currency, the bank guilder. Lucien Gillard (2004) calls it the European guilder (le florin européen), and Adam Smith devotes many pages to explaining how the bank guilder works (Smith 1776: 446–55). The model of the Wisselbank as a state bank was adapted throughout Europe, including the Bank of Sweden (1668) and the Bank of England (1694). - De Vries, Jan; Woude, Ad van der (1997). The First Modern Economy: Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500–1815

- Gordon, John Steele (1999). The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power: 1653–2000. "The Dutch invented modern capitalism in the early seventeenth century. Although many of the basic concepts had first appeared in Italy during the Renaissance, the Dutch, especially the citizens of the city of Amsterdam, were the real innovators. They transformed banking, stock exchanges, credit, insurance, and limited-liability corporations into a coherent financial and commercial system."

- Gordon, Scott (1999). Controlling the State: Constitutionalism from Ancient Athens to Today, p. 172. "In addition to its role in the history of constitutionalism, the republic was important in the early development of the essential features of modern capitalism: private property, production for sale in general markets, and the dominance of the profit motive in the behavior of producers and traders."

- Sayle, Murray (5 April 2001). "Japan goes Dutch". London Riview of Books, Vol. 23 No. 7. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

While Britain’s was the first economy to use fossil energy to produce goods for market, the most characteristic institutions of capitalism were not invented in Britain, but in the Low Countries. The first miracle economy was that of the Dutch Republic (1588–1795), and it, too, hit a mysterious dead end. All economic success contains the seeds of stagnation, it seems; the greater the boom, the harder it is to change course when it ends.

- Schilder, Gunther (1985). The Netherland Nautical Cartography from 1550 to 1650

- Woodward, David, ed (1987). Art and Cartography: Six Historical Essays, p. 147–74

- Paine, Lincoln P. (2000). Ships of Discovery and Exploration

- Day, Alan (2003). The A to Z of the Discovery and Exploration of Australia, p. xxxvii–xxxviii

- The Dutch made significant contributions to the law of the sea, law of nations (public international law) and company law

- Weber, Wolfgang (26 August 2002). "The end of consensus politics in the Netherlands (Part III: The historical roots of consensus politics)". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Russell, Bertrand (1945). A History of Western Philosophy

- Van Bunge, Wiep (2001). From Stevin to Spinoza: an Essay on Philosophy in the Seventeenth-Century Dutch Republic

- Van Bunge, Wiep (2003). The Early Enlightenment in the Dutch Republic 1650–1750

- "The triple helix in Dutch Life Sciences Health". Holland Trade. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Frisians, specifically West Frisians, are an ethnic group; present in the North of the Netherlands; mainly concentrating in the Province of Friesland. Culturally, modern Frisians and the (Northern) Dutch are rather similar; the main and generally most important difference being that Frisians speak West Frisian, one of the three sub-branches of the Frisian languages, alongside Dutch.

West Frisians in the general do not feel or see themselves as part of a larger group of Frisians, and, according to a 1970 inquiry, identify themselves more with the Dutch than with East or North Frisians. Because of centuries of cohabitation and active participation in Dutch society, as well as being bilingual, the Frisians are not treated as a separate group in Dutch official statistics. - Grimbly, Shona (2001). Atlas of Exploration, p. 47

- Mills, William J. (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1, p. 62–65

- Pletcher, Kenneth (2010). The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World, p. 162

- Arlov (1994): 9

- Arlov (1994): 10

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 833.

- Whitfield, Peter (1998). New Found Lands: Maps in the History of Exploration. UK: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92026-4.

- "Search for Barents: Evaluation of Possible Burial Sites on North Novaya Zemlya, Russia", Jaapjan J. Zeeberg et al., Arctic Vol. 55, No. 4 (December 2002) p. 329–338

- J.P. Sigmond and L.H. Zuiderbaan (1979) Dutch Discoveries of Australia. Rigby Ltd, Australia. p. 19–30 ISBN 0-7270-0800-5

- McIntyre, K.G. (1977) The Secret Discovery of Australia, Portuguese ventures 200 years before Cook, Souvenir Press, Menindie ISBN 0-285-62303-6

- Robert J. King, "The Jagiellonian Globe, a Key to the Puzzle of Jave la Grande", The Globe: Journal of the Australian Map Circle, No. 62, 2009, p. 1–50.

- Robert J. King, "Regio Patalis: Australia on the map in 1531?", The Portolan, Issue 82, Winter 2011, p. 8–17.

- Menzies, Gavin (2002). 1421: The year China discovered the world. London: Bantam Press. ISBN 0-06-053763-9.

- Credit for the discovery of Australia was given to Frenchman Binot Paulmier de Gonneville (1504) in Brosses, Charles de (1756). Histoire des navigations aux Terres Australe. Paris.

- In the early 20th century, Lawrence Hargrave argued from archaeological evidence that Spain had established a colony in Botany Bay in the 16th century.

- Dikshitar, V. R. Ramachandra (1947). Origin and Spread of the Tamils. Adyar Library. p. 30.

- This claim was made by Allan Robinson in his self-published In Australia, Treasure is not for the Finder (1980); for discussion, see Henderson, James A. (1993). Phantoms of the Tryall. Perth: St. George Books. ISBN 0-86778-053-3.

- Day, Alan (2003). The A to Z of the Discovery and Exploration of Australia, p. 115

- Seddon, George (2005). The Old Country: Australian Landscapes, Plants and People, p. 28

- McHugh, Evan (2006). 1606: An Epic Adventure, p. 16

- Howgego, Raymond John (1 January 2006). Encyclopedia of Exploration 1850 to 1940: The Oceans, Islands and Polar Regions ; a Comprehensive Reference Guide to the History and Literature of Exploration, Travel and Colonization in the Oceans, the Islands, New Zealand and the Polar Regions from 1850 to the Early Decades of the Twentieth Century. Hordern House. ISBN 978-1-875567-44-7.

- Grimbly, Shona (2001). Atlas of Exploration, p. 107–08

- Broomhall, Susan (22 November 2013). "Australians might speak Dutch if not for strong emotions". The Conversation Media Group. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John; Macintyre, Stuart (1998). The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553597-9. p. 233.

- Mills, William J. (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1, p. 332–33

- McHugh, Evan (2006). 1606: An Epic Adventure. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. pp. 44–57. ISBN 978-0-86840-866-8.

- Garden 1977, p.8.

- Fenton, James (1884). A History of Tasmania: From Its Discovery in 1642 to the Present Time

- Pletcher, Kenneth (2010). The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World, p. 122–25

- Kirk, Robert W. (2012). Paradise Past: The Transformation of the South Pacific, 1520–1920, p. 31

- Newman, Terry (2005). "Appendix 2: Select chronology of renaming". Becoming Tasmania – Companion Web Site. Parliament of Tasmania. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- "The Tamil Bell", Te Papa

- Sridharan, K. (1982). A maritime history of India. Government of India. p. 45.

- Kerry R. Howe (2003). The Quest for Origins: Who First Discovered and Settled New Zealand and the Pacific Islands? pp 144–45 Auckland:Penguin.

- New Zealand Journal of Science. Wise, Caffin & Company. 1883. p. 58. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- New Zealand Institute (1872). Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. New Zealand Institute. pp. 43–. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Welcome to Rapa Nui – Isla de Pascua – Easter Island", Portal RapaNui, the island's official website, archived from the original on 1 November 2011

- "Calculate the Date of Easter Sunday", Astronomical Society of South Australia. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- An English translation of the originally Dutch journal by Jacob Roggeveen, with additional significant information from the log by Cornelis Bouwman, was published in: Andrew Sharp (ed.), The Journal of Jacob Roggeveen (Oxford 1970).

- Ridpath, Ian (1988). Star Tales, p. 9–10

- Lankford, John (1997). History of Astronomy: An Encyclopedia, p. 161

- Stephenson, Bruce; Bolt, Marvin; Friedman, Anna Felicity (2000). The Universe Unveiled: Instruments and Images Through History, p. 24

- Kanas, Nick (2007). Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography, p. 119–21

- Gendler, Robert; Christensen, Lars Lindberg; Malin, David (2011). Treasures of the Southern Sky, p. 14

- Simpson, Phil (2012). Guidebook to the Constellations: Telescopic Sights, Tales, and Myths, p. 559–61

- Ridpath, Ian (2012). A Dictionary of Astronomy (Oxford Paperback Reference), p. 96

- Brienen, Rebecca Parker (2006). Visions of Savage Paradise: Albert Eckcourt, Court Painter in Colonial Dutch Brazil, 1637–1644

- Van Groesen, Michiel (2014). The Legacy of Dutch Brazil

- Spenlé, Virginie (2011). ""Savagery" and "Civilization": Dutch Brazil in the Kunst- and Wunderkammer". Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, JHNA. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Franklin, Wayne (1979). Discoverers, Explorers, Settlers: The Diligent Writers of Early America, p. 21–22

- Jacobs, Jaap (2009). The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America, p. 2

- Jameson, John (2009). Narratives of New Netherland, 1609–1664, p. 288–91

- Huigen, Siegfried; de Jong, Jan L. (2010). The Dutch Trading Companies as Knowledge Networks, p. 103

- Van der Donck, Adriaen (2010). Description of the New Netherlands

- Lach, Donald F.; Van Kley, Edwin J. (1993). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 1: Trade, Missions, Literature, p. 487

- Lee, Peter H. (1996). Sourcebook of Korean Civilization: Volume 2: From the Seventeenth Century to the Modern Period, p. 109

- Lee, Kenneth B. (1997). Korea and East Asia: The Story of a Phoenix, p. 122

- Brook, Timothy (2009). Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World, p. 199–200

- Seth, Michael J. (2011). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present, p. 227–28

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History, p. 316

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Korea, 1600–1800 A.D. (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Kim Jin-u (19 July 2008). "Recollections on the First Encounters of Joseon and Western Powers (Book Reviews)". KOREA FOCUS. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Sohn Ji-ae (19 November 2013). "Blue-eyed Korean Bak Yeon loves Joseon". Korea.net. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Lach, Donald F.; Van Kley, Edwin J. (1993). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 1: Trade, Missions, Literature, p. 486–87

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2003). First Globalization: The Eurasian Exchange, 1500–1800, p. 152–53

- Nahm, Andrew C.; Hoare, James (2004). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Korea, p. 241

External links

- Daily Dutch Innovation

- Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, Episode 6: Travellers' Tales (Documentary TV Series by Carl Sagan):

- Civilisation, chapter 8/13: The Light of Experience (Documentary TV Series by Kenneth Clark)