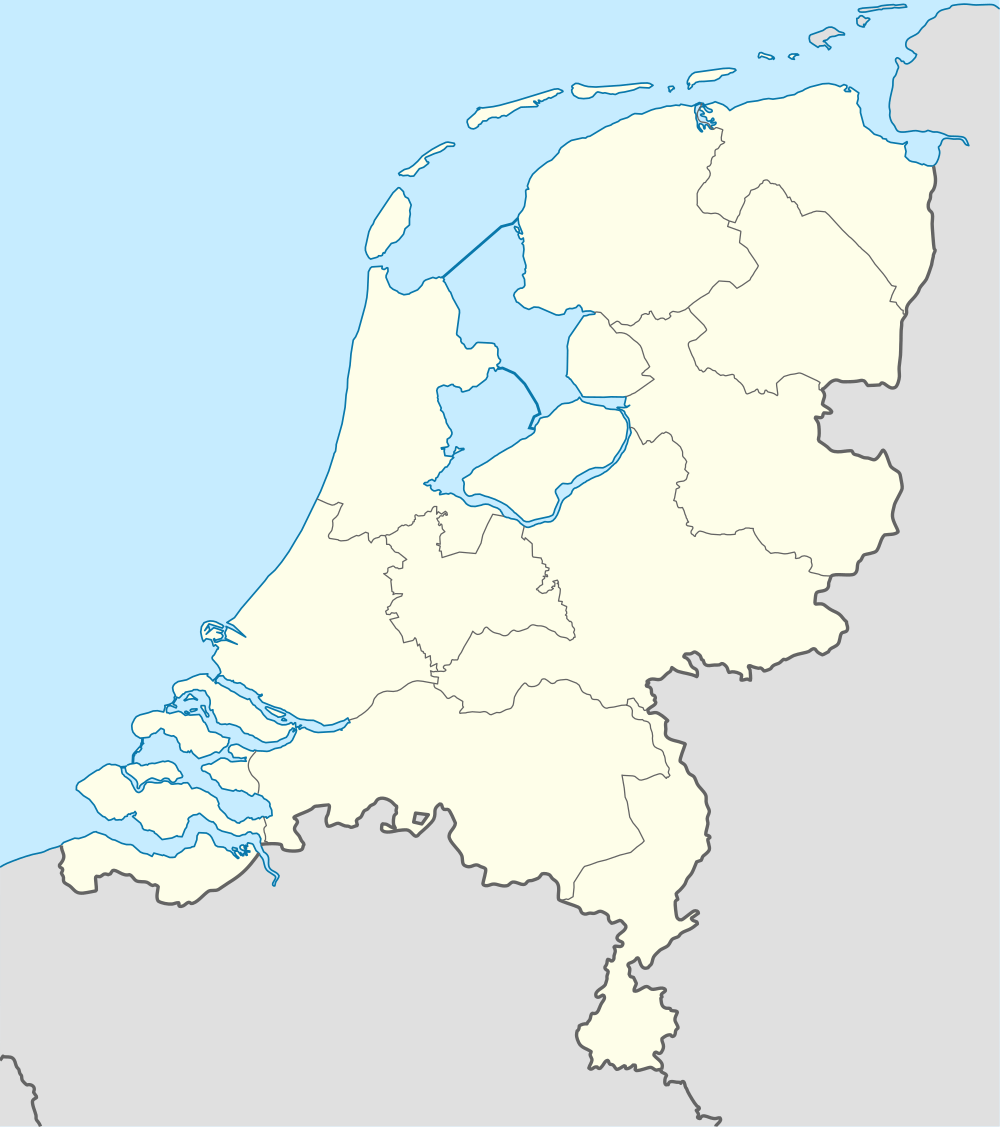

List of World Heritage Sites in the Netherlands

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of importance to cultural or natural heritage as described in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, established in 1972.[1] The Netherlands accepted the convention on 26 August 1992, making its natural and historical sites eligible for inclusion on the list.[2]

As of 2020, there are ten properties in the Kingdom of the Netherlands inscribed on the World Heritage List.[3][4][5]. Nine of those sites are in the Netherlands and one is in Curaçao, in the Caribbean. The Netherlands and Curaçao are both constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Nine sites are cultural properties and one is a natural property.[2] The first site added to the list was Schokland and Surroundings in 1995. The last site on the current list was added in 2014. The transnational site Wadden Sea is shared with Denmark and Germany. There are currently six properties on the tentative list. Two of these sites are entirely in the Netherlands, two are transnational nominations shared with Belgium and Germany, respectively, one is in Curaçao, and one is in Bonaire, which is a special municipality of the Netherlands, located in the Caribbean.[2]

World Heritage Sites

UNESCO lists sites under ten criteria; each entry must meet at least one of the criteria. Criteria i through vi are cultural, whereas vii through x are natural.[6]

| Site | Image | Location | Year listed | UNESCO data | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schokland and Surroundings |  |

Noordoostpolder, Flevoland | 1995 | 739; iii, v (cultural) | Schokland symbolizes the struggle of the people of the Netherlands against the sea. It is a peninsula which had been inhabited since prehistoric times, it became an island in the 15th century, until it was completely encroached by the Zuiderzee in 1859. In the 1940s the Noordoostpolder was created and consequently Schokland was reclaimed.[7] |

| Defence Line of Amsterdam |  |

North Holland and Utrecht | 1996 | 759; ii, iv, v (cultural) | The defence line around Amsterdam was built between 1883 and 1920. The fortification is based on the principle of controlling the waters around a city. It contains a network of 45 armed forts and can temporarily flood polders extending 135 kilometres (84 mi) around Amsterdam.[8] |

| Mill Network at Kinderdijk-Elshout | Alblasserdam and Nieuw-Lekkerland, South Holland | 1997 | 818; i, ii, iv (cultural) | This property is an example of the human-made landscape created by draining the water from the polders. Construction of hydraulic works began in the Middle Ages to create the land for agriculture and to settle. Technological heritage includes high- and low-lying drainage and transport channels for superfluous polder water, embankments and dikes, 3 pumping stations, 2 discharge sluices, 2 Water Board Assembly Houses, and 19 drainage mills, the majority of which were constructed between 1738 and 1740.[9] | |

| Historic Area of Willemstad, Inner City and Harbour, Curaçao |  |

Willemstad, Curaçao | 1997 | 819; ii, iv, v (cultural) | Willemstad was established as a trading settlement by the merchants from the Netherlands in 1634. The modern town consists of several historic districts, which reflect the mix of Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese cultural influences, as well as the Afro-Caribbean. Several historic houses are painted in bright colours, which is a tradition dating to the early 19th century.[10] |

| Ir.D.F. Woudagemaal (D.F. Wouda Steam Pumping Station) |  |

Lemmer, Lemsterland, Friesland | 1998 | 867; i, ii, iv (cultural) | The Wouda Steam Pumping Station is a steam-powered installation to prevent the flooding of the low-lying areas of Friesland. It started operating in 1920. When built, it was the largest and the technologically most advanced steam pumping station in the world. It still functions today.[11] |

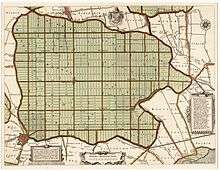

| Droogmakerij de Beemster (Beemster Polder) |  |

Beemster, North Holland | 1999 | 899, i, ii, iv (cultural) | Beemster Polder is the first polder that was created by reclaiming land from a lake. It was drained in 1612, which was made possible by advancements in windmill technology. The polder was laid down in a geometric pattern, in line with the Renaissance planning principles. The basic plot is a rectangle of 180 metres (590 ft) by 900 metres (3,000 ft), four units make up a square. The pattern of roads and watercourses runs north to south and east to west. The polder is still used for agriculture.[12] |

| Rietveld Schröderhuis (Rietveld Schröder House) | Utrecht, Utrecht | 2000 | 965; i, ii (cultural) | The Rietveld Schröder House was built in 1924. It was commissioned by Truus Schröder-Schräder and designed by Gerrit Thomas Rietveld. The house is one of the best known examples of De Stijl movement. It is a small one-family house with a flexible interior spatial arrangement, which allowed gradual changes over time in accordance with changes in functions. It is now preserved as a museum.[13] | |

| The Wadden Sea* |  |

Friesland, Groningen, and North Holland | 2009 | 1314; viii, ix, x (natural) | The Wadden Sea is the largest unbroken system of intertidal sand and mud flats in the world. It is an important biodiversity spot, harbouring species such as harbour seal, grey seal, and harbour porpoise. The sites in Germany and the Netherlands were inscribed to the World Heritage List in 2009, the site in Denmark was added in 2014.[14] |

| Seventeenth-century canal ring area of Amsterdam inside the Singelgracht |  |

Amsterdam, North Holland | 2010 | 1349; i, ii, iv (cultural) | The Amsterdam Canal District was designed at the end of the 16th century and constructed in the 17th century, as a new and entirely artificial port city. The canals are laid out in concentric arcs, intersected with radial waterways and streets. The majority of the houses erected in the 17th and 18th centuries are preserved, while the old civil and hydraulic structures have generally been replaced. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Amsterdam was seen as a reference model for several projects around the world.[15] |

| Van Nelle Factory |  |

Rotterdam, South Holland | 2014 | 1441; ii, iv (cultural) | The factory was built in the 1920s as a food processing and packaging plant for coffee, tea, and tobacco. It was designed by Leendert van der Vlugt and represents a new concept of factory, a symbol of the modernist and functionalist culture of the inter-war period. The façades are made of steel and glass, providing daylight to the workers. The industrial activities in the factory ceased in the 1990s, the property is now run by a new owner.[16] |

Tentative list

In addition to sites inscribed on the World Heritage list, member states can maintain a list of tentative sites that they may consider for nomination. Nominations for the World Heritage list are only accepted if the site was previously listed on the tentative list.[17] As of 2020, the Netherlands has recorded six sites on its tentative list.[18]

| Site | Image | Location | Year listed | UNESCO criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonaire Marine Park |  |

Bonaire, Caribbean Netherlands | 2011 | vii, ix (natural) | The park consists of 2,700 hectares of coral reef, seagrass beds and mangroves. It is the habitat of over 50 varieties of stony coral and over 350 species of reef fish, as well as a nesting ground for sea turtles. The coral reefs are the least degraded in the entire Caribbean Sea.[19] |

| Eise Eisinga Planetarium |  |

Franeker, Friesland | 2011 | i, ii, iv (cultural) | The Royal Eise Eisinga Planetarium in Franeker is the oldest working planetarium in the world. It includes an orrery, a mechanical model of the Solar System, that was built by Eise Eisinga between 1774 and 1781. It is still fully operational.[20] |

| Koloniën van Weldadigheid (agricultural pauper colony)* |  |

Veenhuizen, Noordenveld, Drenthe, | 2011 | v, vi (cultural) | In the aftermath of Napoleonic Wars in Europe, large sections of the population of the Low Countries were left impoverished. To address the social issues, the Society of Benevolence was founded in 1818 and, under the supervision of Johannes van den Bosch, constructed seven agricultural colonies for families, orphans, beggars, and retired military personnel. This approach was innovative with the combination of education, healthcare and (forced) labor to ensure the self-sufficiency of the colonies. The tentative site is shared with Belgium.[21] |

| Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie | Gelderland, North Brabant, North Holland, South Holland, and Utrecht | 2011 | ii, iv, v (cultural) | Similar to the World Heritage Site Defence Line of Amsterdam, the Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie is a military defence line that used flooding of the fields to keep out invaders. It runs from Fort Naarden to Fort Steurgat in the Biesbosch and includes forts, casemates, sluices, and wooden houses.[22] | |

| Plantations in West Curaçao | Curaçao | 2011 | ii, iv, v (cultural) | Four plantations included in this nomination (Ascencion, San Juan, Savonet, and Knip) demonstrate the specific type of Dutch plantations operating in a dry tropical climate. Due to the climate, they faced issues with the water management. As opposed to other plantations in the Caribbean, they focused on several crops and not only sugar. They were run on slave labor and were active from the 17th to the early 20th century.[23] | |

| Frontiers of the Roman Empire — The Lower German Limes (Netherlands)* |  |

Gelderland, South Holland, and Utrecht | 2018 | ii, iii, iv (cultural) | The Lower German Limes protected the Roman province of Germania Inferior (Lower Germany), along the river Rhine from the Rhenish Massif to the North Sea coast. The fortifications were established in the late 1st century BCE and remained in use until the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire in the early 5th century CE. The tentative site is shared with Germany. In the Netherlands, there are 26 individual components listed, which include remains of forts, towns, roads, and other infrastructure. This tentative site is a distinct site from the existing World Heritage Site Frontiers of the Roman Empire, which is listed in Germany and the United Kingdom and also features sites related to the Roman Limes.[24][25] |

References

- "The World Heritage Convention". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "The Netherlands". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "World Heritage Sites". www.holland.com. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Neale, Abbie (10 December 2019). "10 World Heritage Sites in the Netherlands: the best monuments of Holland". dutchreview.com. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Joyce Chepkemoi (25 April 2017). "UNESCO World Heritage Sites In The Netherlands". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – The Criteria for Selection". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Schokland and Surroundings". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Defence Line of Amsterdam". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Mill Network at Kinderdijk-Elshout". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Historic Area of Willemstad, Inner City and Harbour, Curaçao". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Ir.D.F. Woudagemaal (D.F. Wouda Steam Pumping Station)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Droogmakerij de Beemster (Beemster Polder)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Rietveld Schröderhuis (Rietveld Schröder House)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "The Wadden Sea". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Seventeenth-century canal ring area of Amsterdam inside the Singelgracht". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Van Nelle Factory". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Tentative Lists". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – Tentative Lists: the Netherlands". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- "Bonaire Marine Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Eise Eisinga Planetarium". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Koloniën van Weldadigheid (agricultural pauper colony)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Plantations in West Curaçao". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Frontiers of the Roman Empire — The Lower German Limes (Netherlands)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Frontiers of the Roman Empire". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2020.