Lancaster, Lancashire

Lancaster (/ˈlæŋkəstər/,[2][3][4][5]/ˈlænkæs-/)[6] is a cathedral city and the county town of Lancashire, England. It stands on the River Lune and has a population of 52,234. The wider City of Lancaster local government district has a population of 138,375.[7] The House of Lancaster was a branch of the English royal family, whilst the Duchy of Lancaster holds large estates on behalf of Elizabeth II, who is also the Duke of Lancaster. As an ancient settlement, it is marked by Lancaster Castle, Lancaster Priory Church, Lancaster Cathedral and the Ashton Memorial. It is home to Lancaster University and has a campus of the University of Cumbria.

| Lancaster | |

|---|---|

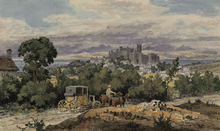

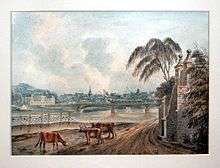

View over Lancaster, with the Ashton Memorial in the distance and the spire of Lancaster Cathedral | |

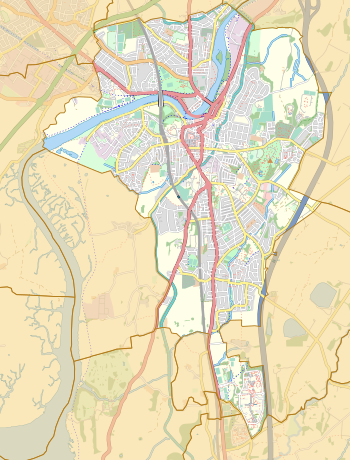

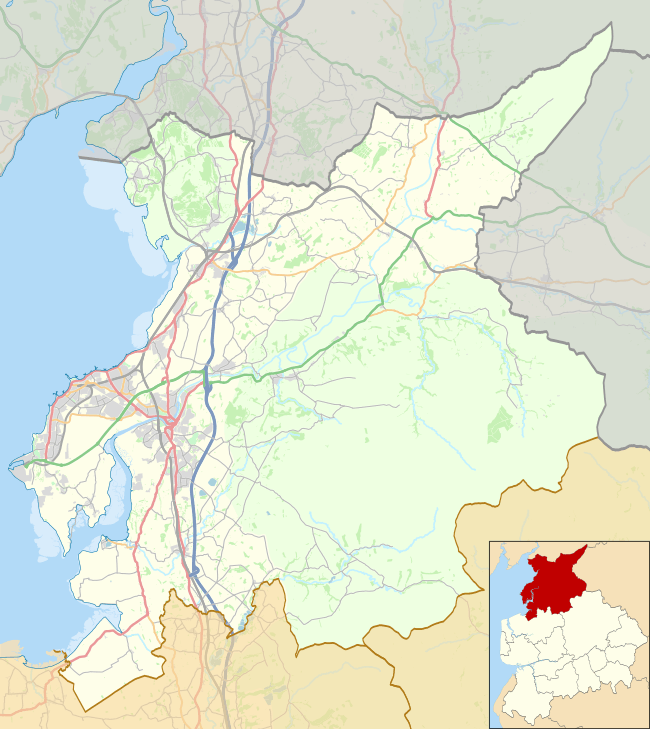

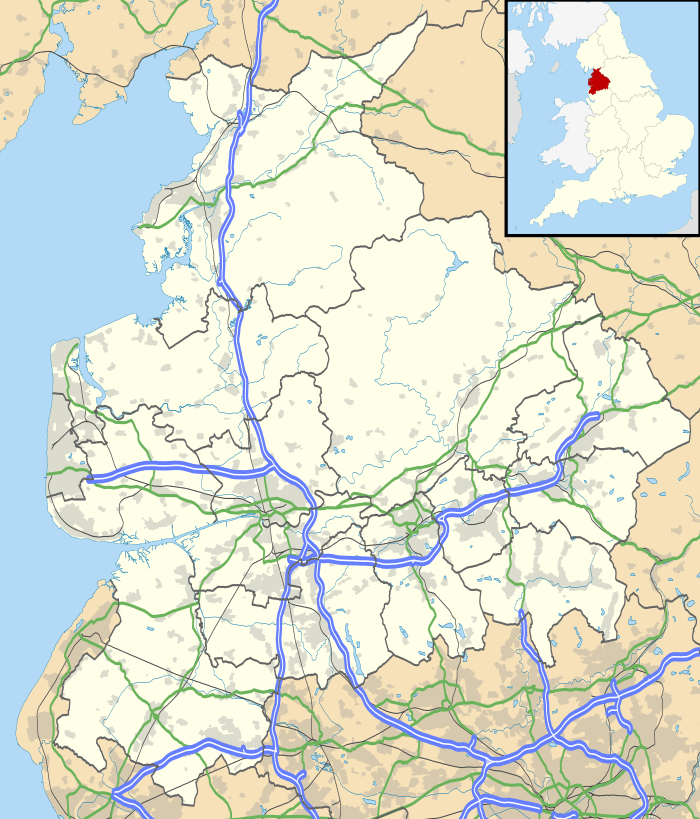

Lancaster Shown within the City of Lancaster district  Lancaster Location within Lancashire | |

| Population | 52,234 [1] |

| Demonym | Lancastrian |

| OS grid reference | SD475615 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LANCASTER |

| Postcode district | LA1, LA2 |

| Dialling code | 01524 |

| Police | Lancashire |

| Fire | Lancashire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament |

|

History

The city's name was first recorded in the Domesday Book in 1086 as Loncastre, where "Lon" refers to the River Lune, and "castre", from the Old English cæster and Latin castrum for "fort", refers to the Roman fort which stood at the site.[8]

Roman and Saxon eras

A Roman fort was built by the end of the 1st century AD on the hill where Lancaster Castle now stands, and possibly as early as the AD 60s, based on Roman coin evidence.[9][10] The coin evidence also suggests that the fort was not continuously inhabited in those early years.[11] It was rebuilt in stone around AD 102.[12] The fort's name is known only in an abbreviated form; the only evidence is a Roman milestone found 4 miles outside Lancaster, with an inscription ending L MP IIII, meaning "from L — 4 miles".[13] The name of the fort was probably Calunium.[14]

Roman baths were discovered in 1812 and can be seen near the junction of Bridge Lane and Church Street. There was presumably a bath-house belonging to the 4th-century fort. The Roman baths incorporated a reused inscription of the Gallic Emperor Postumus, dating from AD 262–266. The 3rd-century fort was garrisoned by the ala Sebosiana and the numerus Barcariorum Tigrisiensium.[15]

The ancient Wery Wall was identified in 1950 as the north wall of the 4th-century fort, which constituted a drastic remodelling of the 3rd-century one, while retaining the same orientation. Exceptionally the later fort is the only example in north-west Britain of a 4th-century type, with massive curtain-wall and projecting bastions typical of the Saxon Shore or in Wales. The extension of this technique as far north as Lancaster shows that the coast between Cumberland and North Wales was not left defenceless after the attacks on the west coast and the disaster in the Carausian Revolt of AD 296, following on from those under Albinus in AD 197.

The fort underwent a few more extensions, and at its largest area it was 9–10 acres (4–4 ha).[16] The evidence suggests that the fort remained active up to the end of Roman occupation of Britain in the early 5th century.[17]

Little is known about Lancaster between the end of Roman rule in Britain in the early 5th century and the Norman Conquest in the late 11th century. Despite a lack of documentation from the period, it is likely that Lancaster was still inhabited. Lancaster was on the fringes of the kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria, and over time, control may have changed from one to the other.[18] Archaeological evidence suggests there was a monastery on or near the site of today's Lancaster Priory by the 700s or 800s. For example, an Anglo-Saxon runic cross found at the Priory in 1807, known as "Cynibald's cross", is thought to have been made in the late 9th century. Lancaster was probably one of the numerous monasteries founded under Wilfrid.[19]

Medieval

Following the Norman conquest of England in 1066, Lancaster fell under the control of William I, as stated in the Domesday Book of 1086, which is the earliest known mention of Lancaster in any document. The founding charter of the Priory, dated 1094, is the first known document which is specific to Lancaster.[20] By this time William had given Lancaster and its surrounding region to Roger de Poitou. This document also suggests that the monastery had been refounded as a parish church at some point before 1066.[20]

Lancaster became a borough in 1193 under King Richard I. Its first charter, dated 12 June 1193, was from John, Count of Mortain, who later became King of England.[21]

Lancaster Castle, partly built in the 13th century and enlarged by Elizabeth I, stands on the site of a Roman garrison. Lancaster Castle is well known as the site of the Pendle witch trials in 1612. It was said that the court based in the castle (the Lancaster Assizes) sentenced more people to be hanged than any other in the country outside London, earning Lancaster the nickname, "the Hanging Town".[22] Lancaster also figured prominently in the suppression of Catholicism during the reformation with the execution of at least eleven Catholic priests. A memorial to the Lancaster Martyrs is located close to the city centre.

The traditional emblem for the House of Lancaster is a red rose, the Red Rose of Lancaster, similar to that of the House of York, which is a white rose. These names derive from the emblems of the Royal Duchies of Lancaster and York in the 15th century. This erupted into a civil war over rival claims to the throne during the Wars of the Roses.

In more recent times, the term "Wars of the Roses" has been applied to rivalry in sports between teams representing Lancashire and Yorkshire, not just the cities of Lancaster and York. It is also applied to the Roses Tournament in which Lancaster and York universities compete every year.[23]

Lancaster gained its first charter in 1193[24] as a market town and borough, but was not given city status until 1937.[25] Many buildings in the city centre and along St. George's Quay date from the 19th century, built as the port became one of the busiest in the UK and the fourth most important in the UK's slave trade.[26] One prominent Lancaster slave-trader was Dodshon Foster.[27] However, Lancaster's role as a major port was short-lived, as the river began to silt up.[24] Morecambe, Glasson Dock and Sunderland Point served as Lancaster's port for brief periods. Heysham now serves as the district's main port.

Recent history

Lancaster is primarily a service-oriented city. Products of Lancaster include animal feed, textiles, chemicals, livestock, paper, synthetic fibre, farm machinery, HGV trailers and mineral fibres. In recent years, a high technology sector has emerged, as a result of Information Technology and Communications companies investing in the city.

A permanent military presence was established in the town with the completion of Bowerham Barracks in 1880.[28] The Phoenix Street drill hall was completed in 1894.[29]

In March 2004, Lancaster was granted Fairtrade City status.[30]

Lancaster was also home to the European headquarters of Reebok. Following its merger with Adidas, Reebok moved to Bolton and Stockport in 2007.[31]

In May 2015 Queen Elizabeth II visited the castle, as part of the celebrations to commemorate the 750th anniversary of the creation of the Duchy of Lancaster.[32]

Governance

Lancaster and Morecambe have grown into a conurbation. The former City and Municipal Borough of Lancaster and the Municipal Borough of Morecambe and Heysham along with other authorities merged in 1974 to form the City of Lancaster district within the shire county of Lancashire. This was given city status in the United Kingdom and Lancaster City Council is the local governing body for the district. Lancaster is an unparished area and has no separate council. It is divided into wards such as Bulk, Castle, Ellel, John O'Gaunt (named after John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster), Scotforth East, Scotforth West, Skerton East, Skerton West, and University and Scotforth Rural.

Political representation

Most of the city lies in the Lancaster and Fleetwood constituency for elections of Members of Parliament to the House of Commons. The current MP for Lancaster and Fleetwood is Cat Smith of the Labour Party. The Skerton part of the city lies in the Morecambe and Lunesdale constituency represented by David Morris of the Conservative Party.

Before Brexit, it was in the North West England European Parliamentary Constituency.

In the late 1990s and early first decade of the 21st century, the city council was under the control of the Morecambe Bay Independents (MBIs), who campaigned for an independent Morecambe council. In 2003, their influence waned and Labour became the largest party on the council. They formed a coalition with the LibDems and Greens. At the May 2007 local elections, Labour lost ground to the Greens in Lancaster and the MBIs in Morecambe, resulting in no overall control, with all parties represented in a PR administration. The 2011 elections saw Labour emerge as the largest party. They reached a joint administrative arrangement with the Greens.

The 2019 Lancaster City Council election result saw no party in overall control. The Council is run by a coalition of Labour, Green and Liberal Democrat parties with Conservatives and Independents in opposition. At 10 seats, Lancaster has one of the largest Green Party representations in the country.

Geography

Lancaster is the most northerly city in Lancashire, lying three miles (4.8 km) inland from Morecambe Bay on the River Lune (from which it derives its name), and the Lancaster Canal. The settlement gets more hilly from the Lune Valley towards the east, with Williamson Hill in the north-west a notable high point at 109 metres (358 ft).

Green belt

There is a small portion of green belt on the northern fringes of Lancaster, covering the area above its urban area through to Carnforth, helping to keep the adjacent countryside open, and prevent further urban expansion between these and the nearby communities of Morecambe, Hest Bank, Slyne and Bolton-le-Sands.[33]

Transport

Road

The M6 motorway passes to the east of Lancaster, with junctions 33 and 34 to the south and north respectively. The A6 road passes through the city leading southwards to Preston, Chorley and Manchester and northwards to Carnforth, Kendal, Penrith and Carlisle.

The A6 is one of the main historic north–south roads in England. It currently runs from Luton in Bedfordshire to Carlisle in Cumbria. The road passes through Lancaster, giving access to nearby towns such as Carnforth, Kendal and Garstang. The Bay Gateway opened in 2016, linking Heysham and the M6 with a dual carriageway.[34]

The main bus operator in Lancaster is Stagecoach Cumbria & North Lancashire, which offers over thirty services from Lancaster bus station to Lancaster and Morecambe. It also provides frequent services in Lancashire, Cumbria, Greater Manchester, North Yorkshire and services throughout the North West of England. There are frequent buses to Lancaster University, with the number 1 and number 2 services running every 15 and every 10 minutes respectively, both using double-decker buses, as well as the less frequent services 4, 41 and 42.[35]

Rail

Lancaster is served by the West Coast Main Line, which runs through Lancaster railway station. The station was formerly named Lancaster Castle, to differentiate it from Lancaster Green Ayre on the Leeds–Morecambe line, which closed in 1966. There are through train services to and from London, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Manchester, Leeds and Barrow-in-Furness, with a local service to Morecambe.

The long-term aim of the city council is to open a railway station serving the university and south Lancaster, although this is not feasible in the short or medium term with current levels of demand.[36] The Caton–Morecambe section of the former North Western railway is now used as a cycle path.

Water and air

The Lancaster Canal and River Lune pass through the city.

The nearest airports are Manchester, Liverpool and Blackpool.

Cycling

In 2005, Lancaster was one of six English towns chosen to be cycling demonstration towns to promote the use of cycling as a means of transport.[37]

Education

At Bailrigg, just south of the city, is Lancaster University, a research university founded in the 1960s, with an annual income of about £319 million.[38] The university employs 3,000 staff and has 17,415 registered students. It has one of only two business schools in the country to have achieved a six-star research rating[39] and its Physics Department[40] was rated #1 in the United Kingdom in 2008.[41] InfoLab21 at the University is Centre of Excellence for Information and Communication Technologies.[42] LEC (Lancaster Environment Centre) has over 200 staff and shares its premises with the government-funded CEH. In 2017 it was rated 21st nationally for research in The Times Higher league table. For teaching, it obtained the highest Gold ranking for teaching quality in the 2017 government TEF, and in 2018 was ranked 9th for its teaching by The Independent[43] and 9th by The Guardian.[44] The Times Higher placed it 137th worldwide for research, and 58th worldwide for arts and humanities.[45] Lancaster University was named International University of the Year by The Times and The Sunday Times Good University Guide, 2020.[46] The university has overseas campuses in Malaysia, China and Ghana, and a project has been launched to open one in Leipzig, Germany.[46]

Lancaster is also home to a campus of the University of Cumbria – more centrally located on the site of the former St Martin's College – which was inaugurated in 2007. It provides undergraduate and postgraduate courses in the arts, social sciences, business, teacher training, health care and nursing.

Jamea Al Kauthar Islamic College, located in the former Royal Albert Hospital building on Ashton Road, is an independent girls' school, providing an education in a Muslim tradition.[47]

Further education colleges

Secondary schools

- Lancaster Royal Grammar School and Lancaster Girls' Grammar School are a selective-entry grammar schools. In 2016 both were rated in the top fifty state schools in the UK based on the achievement of its students by the Sunday Times.[48]

- Ripley St Thomas Church of England Academy

- Our Lady's Catholic College

- Central Lancaster High School

- Skerton Community High School (now closed)

Primary schools

- Lancaster Steiner School

- Scotforth St Pauls CofE Primary School

- Moorside Primary School

- St Bernadette's Catholic Primary School

- Bowerham Primary School

- The Cathedral Catholic Primary School

- Dallas Road Community Primary School

- Willow Lane (formally Marsh) Community Primary School

- Castle View (formally Ridge) Community Primary School

- Lancaster Christ Church CofE Primary School

- St Joseph's Catholic Primary School

- Skerton St Lukes CofE Primary School

- Lancaster Ryelands Primary School

Special Educational Needs (SEN) Schools

- The Loyne

- Morecambe Road School

Culture

Lancaster has a wide range of historic buildings and venues. The city is fortunate to have retained many fine examples of Georgian architecture. Lancaster Castle, the Priory Church of St. Mary and the Edwardian Ashton Memorial are among many sites of historical importance. The city has numerous museums, including Lancaster City Museum, Maritime Museum, the Cottage Museum,[49] and Judges' Lodgings Museum. Lancaster Friends Meeting House dating from 1708, is the longest continual Quaker meeting site in the world with the original building built in 1677. George Fox, founder of Quakerism, was near the site several occasions in the 1660s and spent two years imprisoned in Lancaster Castle.[50] The meeting house today holds regular Quaker meetings and a wide range of cultural activities including adult learning, meditation, art classes, music and political meetings. The Lancaster Grand Theatre is another one of Lancaster historic cultural venues, under its many names, has been a major part of the social and cultural life of Lancaster since being built in 1782.[51]

Lancaster is known nationally for its Arts scene.[52] There are 600 business and organisations in the region involved directly or indirectly with arts and culture.[53] In 2009 several major arts organisations, based within the district, formed a consortium called Lancaster Arts Partners (LAP) to champion and promote the strategic development of excellent arts activities in Lancaster District.[54] Notable partners include Ludus Dance,[55] More Music,[56] the Dukes[57] and among others. LAP curate and promote "Lancaster First Fridays", a monthly multi-disciplinary mini-festival of the arts under their brand "Lancaster Arts City". Lancaster University has its public arts organisation, part of LAP, known as Lancaster Arts at Lancaster University which programmes work for the public into campus venues including; Lancaster's Nuffield Theatre, one of the largest professional studio theatres in Europe; the Peter Scott Gallery, holding the most significant collection of Royal Lancastrian ceramics in Britain and the Lancaster International Concerts Series attracting nationally and internationally renowned classical and world-music artists.[58] The Gallery within the Storey Creative Industries Centre is now programmed and run by Lancaster City Council. In 2013 the previous incumbent organisation "The Storey Gallery" moved out of the building and reformed to become "Storey G2".[59] The Storey Creative Industries Centre is also home to Lancaster's Litfest which organises and runs an annual literature festival. In the summer months Williamson Park hosts a number of outdoor performances including the annual Dukes "Play in the Park", which over the past 26 years has attracted 460,000 people, making it the UK's biggest outdoor walkabout theatre event.[60]

Lancaster is known as the Northern City of Ale, with almost 30 pubs serving cask ale, which has grown in popularity.[61][62] Such pubs include the White Cross, the Three Mariners, the Borough and the Water Witch.[61] There are two cask ale breweries in Lancaster: Lancaster Brewery and a microbrewery run by the Borough. There is also a local CAMRA (Campaign for Real Ale) branch at Lunesdale.[63]

The Lancaster Grand Theatre and the Dukes are two of the city's most notable venues for live performances, as well as the Yorkshire House, Robert Gillow, The John O' Gaunt and The Bobin. Throughout the year, various festivals are held in and around the city, such as the Lancaster Music Festival, Lancaster Jazz Festival, and Chinese New Year Celebrations in the city centre as part of the Lancaster Chinese New Year Festival.[64]

Every November the city hosts a daylight and art festival entitled "Light Up Lancaster",[65] which includes one of the biggest fireworks displays in the north-west.[66]

Lancaster has two cinemas in the city centre; the 1930s art deco Regal Cinema closed in 2006.[67] The Gregson Centre is also known for small film screenings and cultural events.

Sport

Lancaster's main football team, Lancaster City, play in the Northern Premier League Premier Division having won promotion as champions of Division One North in 2016–2017. They play their home matches at the Giant Axe, which can take 3,500 (513 seated) and was formed in 1911 originally under the name Lancaster Town F.C. Lancaster City are six-times Lancashire FA Challenge cup winners and in 2010-11 won the Northern Premier League President's cup for a second time. Lancaster John O' Gaunt Rowing Club is the fifth-oldest surviving rowing club in the UK, outside of the universities.[68] It competes nationally at regattas and heads races organised by British Rowing. The clubhouse is located next to the weir at Skerton.

The city entertains contestants in the Lancaster International Youth Games, a multi-sport 'Olympic' style event, featuring competitors from Lancaster's twin towns: Rendsburg (Germany), Perpignan (France), Viana do Castelo (Portugal), Aalborg (Denmark), Almere (Netherlands), Lublin (Poland) and Växjö (Sweden).

Lancaster Cricket Club is sited near the River Lune in Lancaster. It has two senior teams that participate in the Palace Shield. Rugby union is a popular sport in the area, with the local clubs being Vale of Lune RUFC and Lancaster CATS.

Lancaster is home to many golf clubs, including the Golf Centre, Lansil Golf Club, Forest Hills and Lancaster Golf Club. Lancaster also has a Lancaster Amateur Swimming and Waterpolo Club, which competes in the north-west. It trains at Salt Ayre and at Lancaster University Sports Centre. Lancaster is home to a senior team in Great Britain. Water polo is also popular in the area.

The local athletics track situated near the Salt Ayre Sports Centre in which the track is home to both Lancaster and Morecambe AC. The club regularly fields athletes across athletics disciplines, including Track and Field, Cross Country, Road and Fell Running. The club competes in a number of local and national leagues including the Young Athletics League, the Northern Athletics League and the local Mid Lancs League (Cross-Country in Winter, and Track and Field in Summer).

Music

Lancaster has produced a number of successful bands and musicians since the 1990s, notably the drummer Keith Baxter of 3 Colours Red and folk-metal band Skyclad, who also featured Lancaster guitarist Dave Pugh, the thrash metal band D.A.M. were all from Lancaster, recording two albums for the Noise International label, with Dave Pugh appearing on the second.

The all-girl punk-rock band Angelica used the Lancaster Musicians' Co-operative, the main rehearsal and recording studio in the area.

The city has also produced many other musicians, including singer and songwriter John Waite, who first became known as lead singer of The Babys and had a solo #1 hit in the US, "Missing You". As part of the band Bad English, John Waite also had a #1 hit in the Billboard top hundred in the 1970s called "When I See You Smile". Additionally, Paul James, better known as The Rev, former guitarist of English punk band Towers Of London who is now in the band Day 21 and plays guitar live on tour for The Prodigy; Chris Acland, drummer of the early 1990s shoegaze band Lush; Tom English, drummer of North East indie band Maxïmo Park and Steve Kemp, drummer of the indie band Hard-Fi.

Lancaster continues to produce many bands and musicians, such as singer songwriter Jay Diggins and acts like The Lovely Eggs all of which received considerable national radio play and press coverage in recent years. More recently, Lancaster locals Massive Wagons signed to Nottingham-based independent label Earache Records have emerged.

Lancaster is also the founding home of the dance-music sound systems The Rhythm Method and The ACME Bass Company. Pioneers in the field of the free party, these two systems, along with others, forged one of the strongest representations of the genre in the North West of England during the 1990s.

Since 2006, Lancaster Library has hosted a regular series of music events under the Get it Loud in Libraries initiative. Musicians such as The Wombats, The Thrills, Kate Nash, Adele and Bat for Lashes have taken part.[69] Get It Loud in Libraries has gained national exposure, featuring on The One Show on BBC1, as well as seeing its gigs reviewed in The Observer Music Monthly, NME and Art Rocker.[70]

Notable music venues include The Dukes, The Grand Theatre, The Gregson Centre, The Bobbin and The Yorkshire House,[71] which since 2006 has hosted such acts as John Renbourn, Polly Paulusma, Marissa Nadler, Baby Dee, Diane Cluck, Alasdair Roberts, Jesca Hoop, Lach, Jack Lewis, Tiny Ruins and 2008 Mercury Prize nominees Rachel Unthank and the Winterset. Other venues such as The Dalton Rooms, The V Bar, The Park Hotel and The Hall, China Street also play host to Lancaster's diverse music culture, such as the Lancaster Speakeasy[72] or Stylus.[73]

The Lancaster Jazz and Lancaster Music Festivals are both respectively held annually every September and October, based at various venues throughout the city. In 2013 the headline Jazz act was The Neil Cowley Trio who performed at The Dukes, whilst one of the Lancaster Music Festival headline acts was Jay Diggins who performed at The Dalton Rooms.[74]

Media

Heart North Lancashire & Cumbria (formerly "The Bay") was a commercial radio station for north Lancashire and south Cumbria. Its studios are based at St George's Quay in the city and it broadcasts on three frequencies: 96.9 FM (Lancaster), 102.3 FM (Windermere) and 103.2 FM (Kendal). It is now part of the Manchester-based Heart North West.

Beyond Radio is a voluntary, non-profit community radio station for Lancaster and Morecambe and broadcasts on 103.5FM and online.[75] Operated by Proper Community Media (Lancaster) Ltd, the station and broadcasts 24 hours a day from The Old Bowling Pavilion in Palatine Avenue Park, Bowerham. It took over from Diversity FM, the previous community radio station run by Lancaster and District YMCA, which had closed in April 2012. Beyond Radio was granted a five-year community radio licence and launched on 30 July 2016.

Lancaster University has its own student radio station, Bailrigg FM, broadcasting on 87.7 FM, and an online student-run television station called LA1:TV (formerly LUTube.tv)[76] and a student-run newspaper named SCAN.[77]

The city is home to the film production company A1 Pictures, which founded the independent film brand Capture.

Commercially available newspapers include The Lancaster Guardian (a popular tabloid, having changed from broadsheet in May 2011) and The Visitor (a tabloid newspaper mainly targeted at residents of Morecambe). Both newspapers are based on the White Lund Industrial Estate in Morecambe. Virtual Lancaster, a non-commercial volunteer-led resource website also features local news, events and visitor information. It was founded in 1999.

Places of interest

- Greaves Park

- Lancaster Castle

- Lancaster Priory

- Lancaster City Museum

- Lune Millennium Bridge

- Williamson Park

- Ashton Memorial

- Lancaster Cathedral

- Storey Gallery

- The Judges Lodgings

- Ruskin Library at Lancaster University

- Quayside Maritime Museum

- Lancaster Royal Grammar School

- Duke's Playhouse

- The Gregson Centre

- Lancaster Grand Theatre

- Queen Victoria Memorial

- Lancaster Town Hall

- Westfield War Memorial Village

Notable people

Alphabetical by category. All information is taken from each person's Wikipedia page. Notability implies a lengthy period of fame.

Arts and entertainment

- Joe Abercrombie (born 1974) – fantasy writer and film editor, was born in Lancaster and attended LRGS.

- Cherith Baldry (born 1947) – children's and fantasy writer, was born in Lancaster.

- Laurence Binyon (1869–1943) – poet and dramatist, was born in Lancaster.

- Hubert Henry Norsworthy (1885–1961) – organist and composer, died in Lancaster.

- Mabel Pakenham-Walsh (1937–2013) – artist, was born in Lancaster.

- Jon Richardson (born 1982) – comedian, grew up in Lancaster and attended LRGS.

- Thomas Thompson (1880–1951) – writer and broadcaster

- John Waite (born 1952) – rock musician, was born in Lancaster.

- Dustin Demri-Burns (born 1978) – actor, writer and comedian

- Andy Wear (living) – television and stage actor, was born in Lancaster.

- Keith Wilkinson (living) – television news reporter, was born in Lancaster.

Business

- Henry Cort (1741? – 1800) – English ironmaster and inventor, was probably born in Lancaster.

- James Crosby (born 1956) – chief executive of HBOS until 2006, attended LRGS.

- Thomas Edmondson (1792–1851) – businessman and inventor of the Edmondson railway ticket, was born in Lancaster.

- James Williamson (1842–1930) – businessman and politician who created Williamson Park and Ashton memorial, was born in Lancaster and educated at LRGS.

Crime

- Lauren Jeska (born 1974) – a transgender athlete, was convicted of the attempted murder of an official, Ralph Knibbs.[78]

- Edward Stringer, (1819–1863) – convict and prospector, discovered the Walhalla, Victoria goldfield in Australia.[79]

- Buck Ruxton (1899–1936) – marital murderer, resided and practised medicine at 2 Dalton Square.

Politics and journalism

- Henry D. Gilpin (1801–1860) – Attorney General of the United States, was born in Lancaster.

- Erik de Mauny (1920–1997) – foreign correspondent, died in Lancaster.

- Sir Lancelot Sanderson (1863–1944) – Conservative MP and judge, died in Lancaster.

Science and humanities

- J. L. Austin (1911–1960) – philosopher and developer of the theory of speech acts, was born in Lancaster.

- John Ambrose Fleming (1849–1945) – electrical engineer and physicist, was born in Lancaster.

- Edward Frankland (1825–1899) – chemist who originated the concept of valence, was born near Lancaster and educated at LRGS.

- Jaroslav Krejčí (1916–2014) – Czech-British sociologist, was a professor at the University of Lancaster and died in Lancaster.

- Geoffrey Leech (1936–2014) – linguistics researcher, was a professor at the University of Lancaster and died in Lancaster.

- Richard Owen (1804–1892) – biologist who coined the term "dinosaur", lived in Brock Street.

- William Turner (1832–1916) – anatomist and academic, was born in Lancaster.

- Paul Wellings (born 1953) – ecologist, served as a professor and Vice-Chancellor of Lancaster University.

- Gavin Wood (born 1980) – co-founded and headed Ethereum.

Sport

- Michael Allen (1933–1995) – international cricketer, died in Lancaster.

- Arthur Bate (1908–1993) – professional footballer, died in Lancaster.

- James Beattie (born 1978) – professional footballer, was born in Lancaster.

- Harold Douthwaite (1900–1972) – first-class cricketer, was born and died in Lancaster.

- Scott Durant (born 1988) - Olympic gold medal winning rower, was a pupil at Lancaster Royal Grammar School

- Trevor Glover (born 1951) – first-class cricketer and rugby union player, was born in Lancaster.

- William Gregson (1877–1963) – first-class cricketer, died in Lancaster.

- Sarah Illingworth (born 1963) – international cricketer (New Zealand), was born in Lancaster.

- Edward Jackson (1849–1926) – first-class cricketer, was born in Lancaster.

- John Jackson (1841–1906) – first-class cricketer, was born in Lancaster.

- Scott McTominay (born 1996) – professional footballer currently with Manchester United, was born in Lancaster.

- John Pinch (1870–1946) – international rugby union player, was born and died in Lancaster.

- Jason Queally (born 1970) – Olympic gold medal winning cyclist, was a pupil at Lancaster Royal Grammar School.

- Fred Shinton (1883–1923) – professional footballer, died in Lancaster.

- Alan Warriner-Little (born 1962) – champion darts player, was born in Lancaster.

See also

References

- Lancaster City is made up of 9 wards (Bulk, Duke, Castle, Skerton East and West, Scotforth East and West, University and John O'Gaunt. Archived 14 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Lancaster – Dictionary Definition".

- "LANCASTER • DICTIONARY ONE.COM • Definition of Lancaster".

- "Lancaster definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com.

- "the definition of Lancaster".

- Roach, Peter; Hartman, James; Setter, Jane; Jones, Daniel, eds. (2006). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (17th ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-68086-8.

- Evans, Jacqueline. "Lancashire's Population, 2011". Lancashire County Council. Lancashire County Council. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Eilert Ekwall, 'The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Placenames' (1960), 4th edition, p. 285.

- Shotter, p. 5.

- I. A. Richmond: Excavations on the Site of the Roman Fort at Lancaster (1950)

- Shotter, p. 9.

- Shotter, p. 10.

- Rivet, A. L. F.; Smith, Colin (1979). The Place-Names of Roman Britain. London: B. T. Batsford. p. 382. ISBN 0713420774.

- [https://vici.org/vici/12173/ Map, etc. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Birley, CW- XXXIX, p. 222.

- Shotter, p. 14.

- Shotter, p. 27.

- White 2001, p. 33

- White, p. 34.

- White, p. 57.

- White, p. 35.

- "Lancaster Castle".

- Students celebrate..."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 August 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Lancaster Timeline".

- "Former Mayors of the City of Lancaster". Archived from the original on 19 October 2014.

- "Online 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica".

- Andrew White (2003). Lancaster: A History. Phillimore & Co. p. 63.

- "Army: King's Own Royal Regiment, Lancaster – Regimental Depot". BBC. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- "Records of the 1st/5th Battalion, King's Own Royal Lancaster Regiment". King's Own Royal Regiment Museum, Lancaster. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "Cities win Fairtrade recognition". BBC News. 5 March 2004. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- "Reebok in plan to quit town".

- http://www.lancastercastle.com/2015/05/29/her-majesty-the-queen-duke-of-lancaster-visits-lancaster-castle/

- "Environmental studies". Lancaster City Council.

- "Heysham link road opens". ITV News.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Bailrigg Garden Village and South Lancaster Growth" (PDF).

- "My Word Press Website – Just another WordPress site". Archived from the original on 28 October 2007.

- Anon. "University of Lancaster Annual Report". University of Lancaster. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "RAE 2008: Business & Management Studies". Archived from the original on 30 April 2009.

- University, Lancaster. "Physics – Lancaster University".

- "RAE 2008: physics results". 18 December 2008.

- "InfoLab21 – Lancaster University's Centre of excellence for ICT".

- "These are the best universities in 2018". The Independent. 26 April 2017.

- "University league tables 2018". the Guardian.

- "Lancaster University". Times Higher Education (THE). 9 September 2019.

- "Lancaster named International University of the Year". www.lancaster.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Jamea Al Kauthar official website

- "200 invalid-request". www.lrgs.org.uk.

- Council, Lancashire County. "The Cottage Museum".

- "Friends Meeting House, Lancaster – Church/Chapel in Lancaster, Lancaster – Visit Lancashire". Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "History » Lancaster Grand".

- "Arts boss praises city's culture".

- "Economic Impact Study: Executive Summary".

- "About Us". 18 March 2016.

- info@fatmedia.co.uk, copyright 2016: fat media: http://www.fatmedia.co.uk. "Ludus Dance – Dance Classes In Lancaster – Dance School Lancaster".

- info@fatmedia.co.uk, copyright 2016: fat media: http://www.fatmedia.co.uk. "More Music – Education & Music Charity – More Music Morecambe".

- "Home – the Dukes".

- "About Us ‹ Welcome to Lancaster Arts".

- "Storey G2: About StoreyG2 – The new version of Storey Gallery".

- Pidd, Helen (4 July 2013). "Lancaster's Dukes theatre: the great outdoors".

- Price, Chris. "Lancaster Northern City of Ale". www.northerncityofale.co.uk. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "City centre cask ale trail is £16m Holy Grail". www.lancasterguardian.co.uk. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Lunesdale CAMRA: Home Page". www.lunesdalecamra.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Lancaster Chinese New Year Festival – Lancaster Business Improvement District Joins Us for Chinese New Year 2016".

- Light Up Lancaster, May 2016.

- ianjackson (12 March 2012). "Lancaster Fireworks Spectacular 2012". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012.

- "Lancaster Guardian".

- British Rowing Almanack and ARA Year Book 2003. Hammersmith, London: The Amateur Rowing Association. 2003. pp. 351, 352, 355, 356. ISBN 978-0-7146-5251-1.

- "Lancashire County Library and Information Service – Get it Loud in Lancaster Music Library". Lancashire County Council. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The Yorkshire House". Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- "Lancaster Speakeasy".

- "Facebook".

- Tina (9 October 2013). "Lancaster Music Festival – Something for Everyone".

- Online broadcasting Beyond Radio.

- "LA1:TV".

- "SCAN – SCAN: Student Comment and News at Lancaster University".

- Fell-runner admits attempted knife murder of British athletics official |Lancashire Evening Post.

- The Story of Ned Stringer on the website of Toongabbie, Victoria, Australia retrieved January 2017.

- Lancaster City Council, Twin Towns retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "Aalborg Twin Towns". Europeprize.net. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "Miasta Partnerskie Lublina" [Lublin – Partnership Cities]. www.lublin.eu (in Polish). Urząd Miasta Lublin (City of Lublin). Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

Bibliography

- Shotter, David (2001), "Roman Lancaster: Site and Settlement", A History of Lancaster, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 3–31, ISBN 0-7486-1466-4

- White, Andrew (2001), "Continuity, Charter, Castle and County Town, 400–1500", A History of Lancaster, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 33–72, ISBN 0-7486-1466-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lancaster, Lancashire. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lancaster, Lancashire. |

- Lancaster City Council – Homepage of Lancaster City Council

- Ordnance survey map of Lancaster circa 1890

- Regional Europe - Lancaster

- Visit Lancaster Website – Tourism Website for Lancaster