Duchy of Lancaster

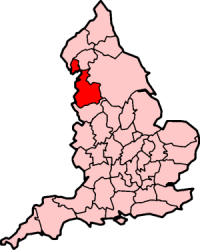

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster.[1][2] The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign.[2][3] The estate consists of a portfolio of lands, properties and assets held in trust for the sovereign and is administered separately from the Crown Estate.[3] The duchy consists of 18,433 ha (45,550 acres) of land holdings (including rural estates and farmland), urban developments, historic buildings and some commercial properties across England and Wales, particularly in Cheshire, Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, Yorkshire, Lancashire and the Savoy Estate in London.[4] The Duchy of Lancaster is one of two royal duchies: the other is the Duchy of Cornwall, which provides income to the Duke of Cornwall, which is traditionally held by the Prince of Wales.

| Duchy of Lancaster | |

|---|---|

| |

| Creation date | 6 March 1351 |

| Monarch | Edward III |

| First holder | Henry of Grosmont |

| Present holder | Elizabeth II |

| Heir apparent | Charles, Prince of Wales |

In the financial year ending 31 March 2018, the estate was valued at about £534 million.[5] The net income of the Duchy is paid to the reigning sovereign as Duke of Lancaster:[2] it amounts to about £20 million per year.[5] As the Duchy is an inalienable asset of the Crown held in trust for future sovereigns, the sovereign is not entitled to the portfolio's capital or capital profits.[2][6] The Duchy of Lancaster is not subject to tax,[7] although the Sovereign has voluntarily paid both income and capital gains tax since 1993.[8] As such, the income received by the Privy Purse, of which income from the Duchy forms a significant part, is taxed once official expenditures have been deducted.[7]

The Duchy is administered on behalf of the sovereign by the chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a government minister appointed by the sovereign on the advice of the prime minister, and by the clerk of the Council.[9] Day-to-day management of the estate's properties and investments is delegated to officers of the Duchy Council,[2][7] while the Chancellor is answerable to Parliament for the effective running of the estate.[10][11][12][13]

The Duchy exercises some powers and ceremonial duties of the Crown in the historic county of Lancashire,[14] which includes the current Lancashire ceremonial county, Greater Manchester and Merseyside as well as the Furness area of Cumbria. Since the Local Government Act 1972, The Queen in Right of the Duchy appoints the High Sheriffs and Lords Lieutenant in Greater Manchester, Merseyside and Lancashire.[15]

History

The Duchy of Lancaster was created for a younger son of King Edward III, John of Gaunt, who acquired its constituent lands through marriage to the Lancaster heiress Blanche. As the Lancaster inheritance it dates to 1265, when Henry III granted his younger son, Edmund Crouchback, lands[16] forfeited by Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester. In 1266, the estates of Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby,[17] another protagonist in the Second Barons' War, were added. In 1267 the estate was granted as the County, Honour and Castle of Lancaster. In 1284 Edmund was given the Manor of Savoy by his mother, Eleanor of Provence, the niece of the original grantee, Peter II, Count of Savoy. Edward III raised Lancashire into a county palatine in 1351, and the holder, Henry of Grosmont, Edmund's grandson, was created Duke of Lancaster.[16] After his death a charter of 1362 conferred the dukedom on his son-in-law John of Gaunt, Earl of Lancaster, and the heirs male of his body lawfully begotten for ever.

The first act of Henry IV was to declare that the Lancastrian inheritance be held separately from the other possessions of the Crown, and should descend to male heirs. This separation of identities was confirmed in 1461 by Edward IV when he incorporated the inheritance and the palatinate responsibilities under the title of the Duchy of Lancaster, and stipulated that it be held separate from other inheritances by him and his heirs, but would however be inherited with the Crown, to which it was forfeited on the attainder of Henry VI.[18] The Duchy thereafter passed to the reigning monarch, and in 1760 its separate identity preserved it from being surrendered with the Crown Estates in exchange for the civil list. It is primarily a landed inheritance belonging to the reigning sovereign (now Elizabeth II).

In 2011, the Duchy established a rebalancing asset plan and sold most of the Winmarleigh estates farms in Lancashire, and donated a plot of land to the Winmarleigh Village Hall committee by June 2012.[19][20]

In 2017, the Paradise Papers revealed that the Duchy held investments in two offshore financial centres, the Cayman Islands and Bermuda. Both are British Overseas Territories of which Queen Elizabeth II is monarch, and nominally appoints governors. Britain handles foreign policy for both islands to a large extent, but Bermuda has been self-governing since 1620. The Duchy's investments included First Quench Retailing off-licences and rent-to-own retailer BrightHouse.[21] Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn posited whether the Queen should apologise, saying anyone with money offshore for tax avoidance should "not just apologise for it, [but] recognise what it does to our society". A spokesman for the Duchy said that all of their investments are audited and legitimate and that the Queen voluntarily pays taxes on income she receives from Duchy investments.[22]

Role

The duchy is the personal property of the monarch and has been since 1399, when the Dukedom of Lancaster, held by Henry of Bolingbroke (Henry IV), merged with the crown on his appropriation of the throne (after the dispossession from Richard II).

The chief officer is the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a position sometimes held by a cabinet minister but always a ministerial post. For at least the last two centuries the estate has been run by a deputy; its chancellor has rarely had any significant duties pertaining to its management but is available as a minister without portfolio.

The monarch derives the privy purse from the revenues of the Duchy. The surplus for the year ended 31 March 2015 was £16 million and the Duchy was valued at just over £472 million.[23] Its land holdings are not to be confused with the Crown Estate, whose revenues have been handed to the Treasury since the 18th century in exchange for the receipt of a yearly payment.

The Duchy Council's primary officers carrying out the estate's day-to-day duties are the Clerk of the Council (the Chief Executive Officer), the Chairman of the Council, and the Chief Finance Officer.[7] The chancellor is responsible for the appointment of the steward and the barmaster of the barmote courts on behalf of the Queen in right of Her Duchy.[24]

Royal prerogative

Both the Duchy of Lancaster and the Duchy of Cornwall have special legal rights not available to other estates held by peers or counties palatine, for example, bona vacantia operates to the advantage of the Duke rather than the Crown throughout the Duchy. Proceeds from bona vacantia in the Duchy are divided between two registered charities.[25][26] Bona vacantia arises, in origin, by virtue of the Royal Prerogative and in some respects remains the position although the right to bona vacantia of the two major categories is now based on statute: Administration of Estates Act 1925[27] and the Companies Act 2006.[28]

There are separate attorneys general for the estates. Generally the exemptions tend to follow the same line: any rights pertaining to the Crown in most areas of the country instead pertain to the Duke in the Duchy. Generally, any Act of Parliament relating to rights of this kind will specifically set out special exemptions for the two Duchies and specify the extent to which they apply. They are subject to strict regulation, especially with respect to auditing and alienation of land.

Holdings

The holdings of the Duchy are divided into six units called surveys, five rural and one urban. The rural surveys make up most of the assets and area but the urban survey generates a greater income. The holdings were accrued over time through marriage, inheritance, gift and confiscation, and in modern times by purchase and sale.[4]

- The holdings include the Lancashire foreshore from Barrow in Furness in the north to the midpoint of the River Mersey in the south.[29]

- Minerals[30]

- Lancaster Castle[31]

- The Lancashire Survey is made up of five rural estates comprising a total of 3,900 hectares[32]

- Patten Arms pub[20]

- Myerscough Estate – held since the 13th century.

- Salwick Estate

- Wyreside Estate

- Whitewell Estate – 2,400 hectares in the Forest of Bowland

- The Cheshire Survey[33]

- Crewe principal estate – now 1,380 hectares

- Crewe Hall Farm offices

- Crewe principal estate – now 1,380 hectares

- The Southern Survey – located mainly in Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire, 3,382 hectares of farm land[34]

- Higham Ferrers estate, Northamptonshire – acquired in 1266 plus 2 additional farms, contains a Vocational Skills Academy, a venture with Moulton College and an 18-hole golf course. In November 2018, an agreement between the Duchy and the AFC Rushden & Diamonds football club resulted in land set aside for the purpose of creating a football field and facilities for the club.[35]

- Ogmore Estate – 1,500 hectares & has an active limestone quarry, a Castle and a golf course

- Castleton estate – 114 hectares of grazing land

- Peveril Castle, Derbyshire

- Peak Cavern tourist attraction

- historic mineral rights

- Bolingbroke Castle, Lincolnshire

- Park Farm

- Donington

- Quadring Fen Farm

- Quadring

- Drayton House Farm, Swineshead

- The Staffordshire Survey – 3,000 hectares in Staffordshire, 60 let houses, including a saw mill, equestrian centres, offices and a private airfield, 600 acres of forest[36]

- Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire

- The Yorkshire Survey – 6,800 hectares[37]

- Goathland estate – 4,100 hectares

- heather moorland, managed as grouse moors, most of which are a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)[38]

- Cloughton estate – 1,000 hectares of Arable land on the Yorkshire coast

- Scalby Lodge

- Pickering estate – mix of arable and livestock farming

- Pickering Castle, North Yorkshire

- Pontefract estate – a single large farm and several commercial properties

- Goathland estate – 4,100 hectares

- Urban Survey[39]

- The Savoy Estate, London

- Harrogate Estate – a care home, hotel and a school

Revenue surplus/income

Revenue surplus or income from the Duchy of Lancaster has increased considerably over time. In 1952, the surplus was £100,000 a year. Almost 50 years later in 2000, the revenue surplus had increased to £5.8M. In 2010, the revenue surplus stood at £13.2M and by 2017, the surplus had grown to £19.2M.[40]

References

- "About the Duchy". Duchy of Lancaster. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- "FAQ". Duchy of Lancaster. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- "Privy Purse and Duchy of Lancaster". Royal Household. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Properties and Estates". Duchy of Lancaster. 3 December 2013. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Financial". Duchy of Lancaster. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Annual Report 2013" (PDF). Duchy of Lancaster. 31 March 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2014.

- "Duchy of Lancaster Management and Finance". Duchy of Lancaster. 2015. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- "Taxation". Royal Household. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "The Government, Prime Minister and Cabinet". UK Government. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- Vernon Bogdanor (November 1995). The Monarchy and the Constitution. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 188. ISBN 0-19-827769-5. The statement in the book is sourced to "Kenneth Clarke, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in Hansard, Standing Committee G, col 11, 17 November 1987"

- "Departmental Land-Duchy of Lancaster". They Work For You. 21 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Hansard Written Answers and Statements". TheyWorkForYou. 14 September 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Duchy Council". TheyWorkForYou. 6 December 2006. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "County Palatine -". www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Palatine High Sheriffs". Duchy of Lancaster. 20 May 2011. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- Styles, Ruth (6 February 2015). "Majority want to stop funding 'minor' royals such as Prince Andrew: Lancaster And Cornwall: The Royal Duchies Explained". Mail Online. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- Maddicott, J. R. (2004). "Ferrers, Robert de, sixth earl of Derby (c. 1239–1279)". In H. G. C. Matthew, Brian Harrison (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1.

- Blackstone, W. (1765) Commentaries on the Laws of England, Introduction, chapter 4 Archived 27 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Sir William Blackstone described the duchy as "separate from the other possessions of the crown in order and government, but united in point of inheritance." (Footnote no. 78.)

- "The Duchy nears completion of Winmarleigh sales". Duchy of Lancaster. 21 June 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Duchy land farm sell-off". Garstang Courier. 31 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Osborne, Hilary (5 November 2017). "Revealed: Queen's private estate invested millions of pounds offshore". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "Paradise Papers: Queen should apologise, suggests Corbyn". BBC. 6 November 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Accounts, Annual Reports and Investments". The Duchy of Lancaster. 18 July 2011. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Barmote Courts". Duchy of Lancaster. 26 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011. ()

- "Benevolent Fund Trustees". Duchy of Lancaster. 25 January 2011. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Terraced house 'belongs to Queen'". BBC News. 3 August 2006. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2010. – provides an example of bona vacantia operating in favour of the Duchy in Gorton in Manchester.

- "In default of any person taking an absolute interest under the foregoing provisions, the residuary estate of the intestate shall belong to the Crown or to the Duchy of Lancaster or to the Duke of Cornwall for the time being, as the case may be, as bona vacantia, and in lieu of any right to escheat." Administration of Estates Act 1925 Section 46

- Section 1016 of the Companies Act 2006 defines the Crown Representative in relation to property vested in the Duchy of Lancaster, as being the Solicitor to that Duchy

- "Holdings: Foreshores". Duchy of Lancaster. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Minerals -". www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Rayner, Gordon (17 July 2012). "Queen's private Duchy of Lancaster estate rises in value above £400m for first time, accounts show". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Unger, Paul (5 June 2009). "Duchy courage". Property Week. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- The Cheshire Survey Archived 3 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- "The Southern Survey -". www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "AFC Rushden & Diamonds Agree Heads Of Terms For New Home". Official Home of AFC Rushden and Diamonds. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- The Staffordshire Survey Archived 1 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- The Yorkshire Survey Archived 12 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- Newton, Grace (21 July 2020). "Three gamekeepers suspended over killing of goshawk on Queen's land". Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- "The Urban Survey -". www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "The Queen has hit the jackpot again. But why does she need so much money?". The Guardian. 19 July 2017. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017.

Further reading

- Somerville, R. (1936). "The Cowcher Books of the Duchy of Lancaster". English Historical Review. 51: 598–615.

- Somerville, R. (1941). "The Duchy of Lancaster Council and Court of Duchy Chamber". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 4th Ser., 23: 159–77.

- Somerville, R. (1946). The Duchy of Lancaster. London.

- Somerville, R. (1947). "Duchy of Lancaster Records". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 4th Ser., 29: 1–17.

- Somerville, R. (1951). "Duchy and County Palatine of Lancaster". Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. 103: 59–67.

- Somerville, R. (1953–70). History of the Duchy of Lancaster. 2 vols, London.

- Somerville, R. (1972). Office-Holders in the Duchy and County Palatine of Lancaster from 1603. Chichester.

- Somerville, R. (1975). "Ordinances for the Duchy of Lancaster". Camden Miscellany XXVI. Camden, 4th Ser., 14: 1–29.