Ida B. Wells

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) was an American investigative journalist, educator, and an early leader in the civil rights movement. She was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[1] Over the course of a lifetime dedicated to combating prejudice and violence, and the fight for African American equality, especially that of women, Wells arguably became the most famous black woman in America.[2]

Ida B. Wells | |

|---|---|

Wells, c. 1893 | |

| Born | Ida Bell Wells July 16, 1862 |

| Died | March 25, 1931 (aged 68) |

| Burial place | Oak Woods Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Ida Bell Wells-Barnett Iola (pen name) |

| Education | Rust College Fisk University |

| Occupation | Civil rights and women's rights activist, journalist and newspaper editor, teacher |

| Spouse(s) | Ferdinand L. Barnett |

| Children | 6 |

| Parent(s) | James Wells and Elizabeth "Izzy Bell" Warrenton |

Born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Wells was freed by the Emancipation Proclamation during the American Civil War. At the age of 16, she lost both her parents and her infant brother in the 1878 yellow fever epidemic. She went to work and kept the rest of the family together with the help of her grandmother. Later, moving with some of her siblings to Memphis, Tennessee, she found better pay as a teacher. Soon, Wells co-owned and wrote for the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper. Her reporting covered incidents of racial segregation and inequality.

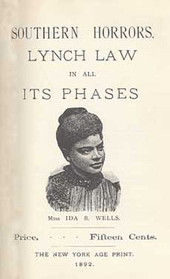

In the 1890s, Wells documented lynching in the United States through her indictment called "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases," investigating frequent claims of whites that lynchings were reserved for black criminals only. Wells exposed lynching as a barbaric practice of whites in the South used to intimidate and oppress African Americans who created economic and political competition—and a subsequent threat of loss of power—for whites. A white mob destroyed her newspaper office and presses as her investigative reporting was carried nationally in black-owned newspapers.

Subjected to continued threats, Wells left Memphis for Chicago. She married and had a family while continuing her work writing, speaking, and organizing for civil rights and the women's movement for the rest of her life. Wells was outspoken regarding her beliefs as a Black female activist and faced regular public disapproval, sometimes including from other leaders within the civil rights movement and the women's suffrage movement. She was active in women's rights and the women's suffrage movement, establishing several notable women's organizations. A skilled and persuasive speaker, Wells traveled nationally and internationally on lecture tours.[3]

In 2020, Wells was posthumously honored with a Pulitzer Prize special citation "[f]or her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching."[4]

Early life

Ida Bell Wells was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862, the first child of James Wells and Elizabeth "Lizzie" (Warrenton). James Wells' father was a white man who impregnated an enslaved black woman named Peggy. Before dying, James' father brought him, aged 18, to Holly Springs to become a carpenter's apprentice, where he developed a skill and worked as a "hired out slave living in town."[5] Lizzie's experience as an enslaved person was quite different. One of 10 children born on a plantation in Virginia, Lizzie was sold away from her family and siblings and tried without success to locate her family following the Civil War.[5] Before the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, Wells’ parents were enslaved to Spires Boling, an architect, and the family lived in the structure now called Bolling–Gatewood House, which has become the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum.[6]

After emancipation, Wells’ father, James Wells, became a trustee of Shaw College (now Rust College). He refused to vote for Democratic candidates during the period of Reconstruction, became a member of the Loyal League, and was known as a "race man" for his involvement in politics and his commitment to the Republican Party.[5] He founded a successful carpentry business in Holly Springs in 1867, and his wife Lizzie became known as a "famous cook".[7]

Ida B. Wells was one of the eight children, and she enrolled in the historically black liberal arts college Rust College in Holly Springs (formerly Shaw College). In September 1878, tragedy struck the Wells family when both of Ida’s parents died during a yellow fever epidemic that also claimed a sibling.[8] Wells had been visiting her grandmother's farm near Holly Springs at the time, and was spared.

Following the funerals of her parents and brother, friends and relatives decided that the five remaining Wells children should be separated and sent to various foster homes. Wells resisted this solution. To keep her younger siblings together as a family, she found work as a teacher in a black elementary school in Holly Springs. Her paternal grandmother, Peggy Wells, along with other friends and relatives, stayed with her siblings and cared for them during the week while Wells was teaching.

But when Peggy Wells died from a stroke and her sister Eugenia died, Wells accepted the invitation of her aunt Fanny and moved with her two youngest sisters to Memphis in 1883.

Early career and anti-segregation activism

—Ida B Wells (1892)[2]

Soon after moving to Memphis, Wells was hired in Woodstock by the Shelby County school system. During her summer vacations she attended summer sessions at Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville. She also attended Lemoyne-Owen College, a historically black college in Memphis. She held strong political opinions and provoked many people with her views on women's rights. At the age of 24, she wrote, "I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge."[9]

On May 4, 1884, a train conductor with the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad[10][11] ordered Wells to give up her seat in the first-class ladies car and move to the smoking car, which was already crowded with other passengers. The previous year, the Supreme Court had ruled against the federal Civil Rights Act of 1875 (which had banned racial discrimination in public accommodations). This verdict supported railroad companies that chose to racially segregate their passengers. When Wells refused to give up her seat, the conductor and two men dragged her out of the car. Wells gained publicity in Memphis when she wrote a newspaper article for The Living Way, a black church weekly, about her treatment on the train. In Memphis, she hired an African-American attorney to sue the railroad. When her lawyer was paid off by the railroad,[12] she hired a white attorney. She won her case on December 24, 1884, when the local circuit court granted her a $500 award. The railroad company appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which reversed the lower court's ruling in 1887. It concluded, "We think it is evident that the purpose of the defendant in error was to harass with a view to this suit, and that her persistence was not in good faith to obtain a comfortable seat for the short ride."[13][14] Wells was ordered to pay court costs. Her reaction to the higher court's decision revealed her strong convictions on civil rights and religious faith, as she responded: "I felt so disappointed because I had hoped such great things from my suit for my people. ... O God, is there no ... justice in this land for us?"[15]

While continuing to teach elementary school, Wells became increasingly active as a journalist and writer. She was offered an editorial position for the Evening Star in Washington, D.C., and she began writing weekly articles for The Living Way weekly newspaper under the pen name "Iola." Under her pen name, she wrote articles attacking racist Jim Crow policies.[16] In 1889, she became editor and co-owner with J. L. Fleming of The Free Speech and Headlight, a black-owned newspaper established by the Reverend Taylor Nightingale and based at the Beale Street Baptist Church in Memphis.

In 1891, Wells was dismissed from her teaching post by the Memphis Board of Education due to her articles that criticized conditions in the black schools of the region. She was devastated but undaunted, and concentrated her energy on writing articles for The Living Way and the Free Speech and Headlight.[17]

Wells was considered to be a well accomplished, successful woman who was well respected among the community. She belonged to the middle class which at the time was considered to be rare for women especially women of color.

Anti-lynching campaign and investigative journalism

The lynching at The Curve in Memphis

In 1889, a black proprietor named Thomas Moss opened the People's Grocery in a South Memphis neighborhood nicknamed "The Curve." Wells was close to Moss and his family, having stood as godmother to his first child. Moss's store did well and competed with a white-owned grocery store across the street, owned by William Barrett.

On March 2, 1892, a young black boy named Armour Harris was playing a game of marbles with a young white boy named Cornelius Hurst in front of the People's Grocery. The two boys got into an argument and a fight during the game. As the black boy Harris began to win the fight, the father of Cornelius Hurst intervened and began to "thrash" Harris. The People's Grocery employees William Stewart and Calvin McDowell saw the fight and rushed outside to defend the young Harris from the adult Hurst as people in the neighborhood gathered in to what quickly became a "racially charged mob."[18]

The white grocer Barrett returned the following day, March 3, 1892, to the People's Grocery with a Shelby County Sheriff's Deputy, looking for William Stewart. But Calvin McDowell, who greeted Barrett, indicated that Stewart was not present. Barrett was dissatisfied with the response and was frustrated that the People's Grocery was competing with his store. Angry about the previous day's mêlée, Barrett responded that "blacks were thieves" and hit McDowell with a pistol. McDowell wrestled the gun away and fired at Barrett—missing narrowly. McDowell was later arrested but subsequently released.[19]

On March 5, 1892, a group of six white men including a sheriff's deputy took electric streetcars to the People's Grocery. The group of white men were met by a barrage of bullets from the People's Grocery, and Shelby County Sheriff Deputy Charley Cole was wounded, as well as civilian Bob Harold. Hundreds of whites were deputized almost immediately to put down what was perceived by the local Memphis newspapers Commercial and Appeal-Avalanche as an armed rebellion by black men in Memphis.[20]

Thomas Moss, a postman in addition to being the owner of the People's Grocery, was named as a conspirator along with McDowell and Stewart. The three men were arrested and jailed pending trial.

Around 2:30 a.m. on the morning of March 9, 1892, 75 men wearing black masks took Moss, McDowell, and Stewart from their jail cells at the Shelby County Jail to a Chesapeake and Ohio rail yard one mile north of the city and shot them dead. The Memphis Appeal-Avalanche reports:

Let me give you thanks for your faithful paper on the lynch abomination now generally practiced against colored people in the South. There has been no word equal to it in convincing power. I have spoken, but my word is feeble in comparison. ... Brave woman!

—Frederick Douglass (1895)[21]

Just before he was killed, Moss said to the mob: "Tell my people to go west, there is no justice here."[22]

After the lynching of her friends, Wells wrote in Free Speech and Headlight urging blacks to leave Memphis altogether:

"There is, therefore, only one thing left to do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons."[23]

The event led Wells to begin investigating lynchings using investigative journalist techniques. She began to interview people associated with lynchings, including a lynching in Tunica, Mississippi, in 1892 where she concluded that the father of a young white woman had implored a lynch mob to kill a black man with whom his daughter was having a sexual relationship, as to "to save the reputation of his daughter."[24]

In May 1892, Wells published an editorial refuting what she called the "that old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern men are not careful, a conclusion might be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women."[25] Wells’ newspaper office was burned to the ground, and she would never again return to Memphis.

Southern Horrors and The Red Record

On October 26, 1892, Wells began to publish her research on lynching in a pamphlet titled Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.[26][27] Having examined many accounts of lynchings due to the alleged "rape of white women", she concluded that Southerners cried rape as an excuse to hide their real reasons for lynchings: black economic progress, which threatened white Southerners with competition, and white ideas of enforcing black second-class status in the society. Black economic progress was a contemporary issue in the South, and in many states whites worked to suppress black progress. In this period at the turn of the century, Southern states, starting with Mississippi in 1890, passed laws and/or new constitutions to disenfranchise most black people and many poor white people through use of poll taxes, literacy tests and other devices. Wells-Barnett recommended that black people use arms to defend against lynching.[28]

She followed-up with greater research and detail in The Red Record (1895), a 100-page pamphlet describing lynching in the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. It also covered black peoples' struggles in the South since the Civil War. The Red Record explored the alarmingly high rates of lynching in the United States (which was at a peak from 1880 to 1930). Wells-Barnett said that during Reconstruction, most Americans outside the South did not realize the growing rate of violence against black people in the South. She believed that during slavery, white people had not committed as many attacks because of the economic labour value of slaves. Wells noted that, since slavery time, "ten thousand Negroes have been killed in cold blood, [through lynching] without the formality of judicial trial and legal execution."

Frederick Douglass had written an article noting three eras of "Southern barbarism" and the excuses that whites claimed in each period.

Wells-Barnett explored these in detail in her The Red Record.

- During slavery time, she noted that whites worked to "repress and stamp out alleged 'race riots'" or suspected slave rebellions, usually killing black people in far higher proportions than any white casualties. Once the Civil War ended, white people feared black people, who were in the majority in many areas. White people acted to control them and suppress them by violence.

- During the Reconstruction Era white people lynched black people as part of mob efforts to suppress black political activity and re-establish white supremacy after the war. They feared "Negro Domination" through voting and taking office. Wells-Barnett urged black people in high-risk areas to move away to protect their families.

- She noted that whites frequently claimed that black men had "to be killed to avenge their assaults upon women". She noted that white people assumed that any relationship between a white woman and a black man was a result of rape. But, given power relationships, it was much more common for white men to take sexual advantage of poor black women. She stated: "Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that black men rape white women." Wells connected lynching to sexual violence, showing how the myth of the black man's lust for white women led to murder of African-American men.

Wells-Barnett gave 14 pages of statistics related to lynching cases committed from 1892 to 1895; she also included pages of graphic accounts detailing specific lynchings. She notes that her data was taken from articles by white correspondents, white press bureaus, and white newspapers. The Red Record was a huge pamphlet, and had far-reaching influence in the debate about lynching. Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases and The Red Record's accounts of these lynchings grabbed the attention of Northerners who knew little about lynching or accepted the common explanation that black men deserved this fate. Generally southern states and white juries refused to indict any perpetrators for lynching, although they were frequently known and sometimes shown in the photographs being made more frequently of such events.

Despite Wells-Barnett's attempt to garner support among white Americans against lynching, she believed that her campaign could not overturn the economic interests whites had in using lynching as an instrument to maintain Southern order and discourage Black economic ventures. Ultimately, Wells-Barnett concluded that appealing to reason and compassion would not succeed in gaining criminalization of lynching by Southern whites.[29]

Wells-Barnett concluded that perhaps armed resistance was the only defense against lynching. Meanwhile, she extended her efforts to gain support of such powerful white nations as Britain to shame and sanction the racist practices of America.[29]

Speaking tours in Britain

Wells travelled twice to Britain in her campaign against lynching, the first time in 1893 and the second in 1894. She and her supporters in America saw these tours as an opportunity for her to reach larger, white audiences with her anti-lynching campaign, something she had been unable to accomplish in America. She found sympathetic audiences in Britain, already shocked by reports of lynching in America.[30]

Wells had been invited for her first British speaking tour by Catherine Impey and Isabella Fyvie Mayo. Impey, a Quaker abolitionist who published the journal Anti-Caste,[31] had attended several of Wells' lectures while traveling in America. Mayo was a well-known writer and poet who wrote under the name of Edward Garrett. Both women had read of the particularly gruesome lynching of Henry Smith in Texas and wanted to organize a speaking tour to call attention to American lynchings. They asked Frederick Douglass to make the trip, but citing his age and health, he declined. He then suggested Wells, who enthusiastically accepted the invitation.[32][33]

In 1894, before leaving the US for her second visit to Great Britain, Wells called on William Penn Nixon, the editor of the Daily Inter-Ocean, a Republican newspaper in Chicago. It was the only major white paper that persistently denounced lynching.[34] After she told Nixon about her planned tour, he asked her to write for the newspaper while in England.[35] She was the first African-American woman to be a paid correspondent for a mainstream white newspaper.[36]

Wells toured England, Scotland and Wales for two months, addressing audiences of thousands,[37] and rallying a moral crusade among the British.[38] She relied heavily on her pamphlet Southern Horrors in her first tour, and showed shocking photographs of actual lynchings in America. On May 17, 1894, she spoke in Birmingham at the Young Men's Christian Assembly and at Central Hall, and staying in Edgbaston at 66 Gough Road.[39]

As a result of her two lecture tours in Britain, she received significant coverage in the British and American press. Many of the articles published at the time of her return to the United States were hostile personal critiques, rather than reports of her anti-lynching positions and beliefs. The New York Times, for example, called her "a slanderous and nasty-nasty-minded Mulatress."[40] Despite these attacks in the white press, Wells had nevertheless gained extensive recognition and credibility, and an international audience of white supporters of her cause.

Marriage and family

In 1895, Wells married attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett,[41] a widower with two sons, Ferdinand and Albert. A prominent attorney, Barnett was a civil rights activist and journalist in Chicago. Like Wells, he spoke widely against lynchings and for the civil rights of African Americans. Wells and Barnett had met in 1893, working together on a pamphlet protesting the lack of Black representation at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Barnett founded The Chicago Conservator, the first Black newspaper in Chicago, in 1878. Wells began writing for the paper in 1893, later acquired a partial ownership interest, and after marrying Barnett, assumed the role of editor.

Wells' marriage to Barnett was a legal union as well as a partnership of ideas and actions. Both were journalists, and both were established activists with a shared commitment to civil rights. In an interview, Wells' daughter Alfreda said that the two had "like interests" and that their journalist careers were "intertwined." This sort of close working relationship between a wife and husband was unusual at the time, as women often played more traditional domestic roles in a marriage.[42]

In addition to Barnett's two children from his previous marriage, the couple had four more: Charles, Herman, Ida, and Alfreda. In the chapter of her Crusade For Justice autobiography called "A Divided Duty," Wells described the difficulty she had splitting her time between her family and her work. She continued to work after the birth of her first child, traveling and bringing the infant Charles with her. Although she tried to balance her roles as a mother and as a national activist, she was not always successful. Susan B. Anthony said she seemed "distracted."[43]

African-American leadership

The 19th century's acknowledged leader for African-American civil rights, Frederick Douglass praised Wells' work, giving her introductions and sometimes financial support for her investigations. When he died in 1895, Wells was perhaps at the height of her notoriety, but many men and women were ambivalent or against a woman taking the lead in black civil rights at a time when women were not seen as, and often not allowed to be, leaders by the wider society.[44] For the new leading voices, Booker T. Washington, his rival, W. E. B. Du Bois, and more traditionally minded women activists, Wells often came to be seen as too radical.[45] Wells encountered and sometimes collaborated with the others, but they also had many disagreements, while also competing for attention for their ideas and programs. For example, there are differing in accounts for why Wells' name was excluded from the original list of founders of the NAACP. In his autobiography Dusk of Dawn, Du Bois implied that Wells chose not to be included.[46] However, in her autobiography, Wells stated that Du Bois deliberately excluded her from the list.[47]

Organizing in Chicago

Having settled in Chicago, Wells continued her anti-lynching work while becoming more focused on the civil rights of African Americans. She worked with national civil rights leaders to protest a major exhibition, she was active in the national women's club movement, and she ultimately ran for the Illinois State Senate. She also was passionate about women's rights and suffrage. She was a spokeswomen and an advocate for women being successful in the workplace, having equal opportunities, and creating a name for themselves

World's Columbian Exposition

In 1893, the World's Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago. Together with Frederick Douglass and other black leaders, Wells organized a black boycott of the fair, for its exclusion of African Americans from the exhibits. Wells, Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn, and Wells' future husband, Ferdinand L. Barnett, wrote sections of the pamphlet The Reason Why: The Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition, which detailed the progress of blacks since their arrival in America and also exposed the basis of Southern lynchings. Wells later reported to Albion W. Tourgée that copies of the pamphlet had been distributed to more than 20,000 people at the fair.[44] That year she started work with The Chicago Conservator, the oldest African-American newspaper in the city.

Women's Clubs

Living in Chicago in the late 19th century, Wells was very active in the national Woman's club movement. In 1893, she organized The Women's Era Club, a first-of-its-kind civic club for African-American women in Chicago. It would later be renamed the Ida B. Wells Club in her honor.[46] In 1896, Ida B. Wells took part in the meeting in Washington, D.C. that founded the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs.[48] After Ms. Wells' death, the Ida B. Wells Club went on to do many things. The club advocated to have a housing project in Chicago named after the founder, Ida B. Wells, and succeeded, making history in 1939 as the first housing project named after a colored woman.[49] Ida B. Wells also helped organize the National Afro-American Council.

Wells received much support from other social activists and her fellow club women. Frederick Douglass praised her work: "You have done your people and mine a service ... What a revelation of existing conditions your writing has been for me."[49]

Despite Douglass' praise, Wells was becoming a controversial figure among local and national women's clubs. This was evident when in 1899 the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs intended to meet in Chicago. Writing to the president of the association, Mary Terrell, Chicago organizers of the event stated that they would not cooperate in the meeting if it included Wells. When Wells learned that Terrell had agreed to exclude Wells, she called it "a staggering blow."[50]

School segregation

In 1900, Wells was outraged when the Chicago Tribune published a series of articles suggesting adoption of a system of racial segregation in public schools. Given her experience as a school teacher in segregated systems in the South, she wrote to the publisher on the failures of segregated school systems and the successes of integrated public schools. She then went to his office and lobbied him. Unsatisfied, she enlisted the social reformer Jane Addams in her cause. Wells and the pressure group she put together with Addams are credited with stopping the adoption of an officially segregated school system.[51][52]

Suffrage

Willard controversy

Wells' role in the U.S. suffrage movement was inextricably linked to her lifelong crusade against racism, violence and discrimination towards African Americans. Her view of women's enfranchisement was pragmatic and political.[53] Like all suffragists she believed in women's right to vote, but she also saw enfranchisement as a way for black women to become politically involved in their communities and to use their votes to elect African Americans, regardless of gender, to influential political offices.

As a prominent black suffragist, Wells held strong positions against racism, violence and lynching that brought her into conflict with leaders of largely white suffrage organizations. Perhaps the most notable example of this conflict was her very public disagreement with Frances Willard, the first President of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).[54]

The WCTU was a predominantly white women's organization, with branches in every state and a growing membership. With roots in the call for temperance and sobriety, the organization later became a powerful advocate of suffrage in the U.S.

In 1893 Wells and Willard travelled separately to Britain on lecture tours. Willard was promoting temperance as well as suffrage for women, and Wells was calling attention to lynching in the U.S. The basis of their dispute was Wells' public statements that Willard was silent on the issue of lynching.[55] She referred to an interview Willard had conducted during her tour of the American South, in which she had blamed African Americans' behavior for the defeat of temperance legislation. "The colored race multiplies like the locusts of Egypt," she had said, and "the grog shop is its center of power. ... The safety of women, of childhood, of the home is menaced in a thousand localities."[63]

Although Willard and her prominent supporter Lady Somerset attempted to limit press coverage of Wells' comments, newspapers in Britain in fact provided details of the dispute.

Wells also dedicated a chapter of her 1895 pamphlet A Red Record to juxtapose the different positions that she and Willard held. The chapter titled "Miss Willard's Attitude" condemned Willard for using rhetoric that promoted violence and other crimes against African Americans in America.

Alpha Suffrage Club

In the years following her dispute with Willard, Wells continued her Anti- Lynching campaign and organizing in Chicago. She focused her work on black women's suffrage in the city following the enactment of a new state law enabling partial women's suffrage. The Illinois Presidential and Municipal Suffrage Bill of 1913 gave women in the state the right to vote for presidential electors, mayor, aldermen and most other local offices; but not for governor, state representatives or members of Congress. Illinois was the first state east of the Mississippi to give women these voting rights.[56]During the membership of Ida B. Wells in the Negro Fellowship League, the organization advocated for women's suffrage alongside its support for the Republican Party in Illinois.[57]

This act was the impetus for Wells and her white colleague Belle Squire to organize the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago in 1913.[32] One of the most important black suffrage organizations in Chicago, the Alpha Suffrage Club was founded as a way to further voting rights for all women, to teach black women how to engage in civic matters and to work to elect African Americans to city offices. Two years after its founding, the club played a significant role in electing Oscar DePriest as the first African-American Alderman in Chicago.[58] The Negro Fellowship League aided alongside the Alpha Suffrage Club in the creation of the Federated Organizations.[57]

As Wells and Squire were organizing the Alpha Club, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was organizing a suffrage parade in Washington D.C. Marching the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson in 1913, suffragists from across the country gathered to demand universal suffrage.[59] Wells, together with a delegation of members from Chicago, attended. On the day of the march, the head of the Illinois delegation told the Wells delegates that the NAWSA wanted "to keep the delegation entirely white."[60] and all African-American suffragists, including Wells were to walk at the end of the parade in a "colored delegation." [61] Instead of going to the back with other African Americans, however, Wells waited with spectators as the parade was underway, and stepped into the white Illinois delegation as they passed by. Wells visibly linked arms with her white suffragist colleagues, Squire and Virginia Brooks for the rest of the parade, demonstrating, according to the Chicago Defender, the universality of the women's civil rights movement.[62]

"Race agitator" to political candidate

During World War I, the U.S. government placed Wells under surveillance, labeling her a dangerous "race agitator."[7] She defied this threat by continuing civil rights work during this period with such figures as Marcus Garvey, Monroe Trotter, and Madam C.J. Walker.[7] In 1917, she wrote a series of investigative reports for the Chicago Defender on the East St. Louis Race Riots.[63] After almost thirty years away, Wells made her first trip back to the South in 1921 to investigate and publish a report on the Elaine Race Riot in Arkansas (published 1922).[63]

In the 1920s, she participated in the struggle for African-American workers rights, urging black women's organizations to support the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, as it tried to gain legitimacy.[7] However, she lost the presidency of the National Association of Colored Women in 1924 to the more diplomatic Mary Bethune.[64] In the late 1920s, Wells remained active in the Republican Party. [18] To challenge what she viewed as problems for African Americans in Chicago, Wells started a political organization named Third Ward Women's Political Club in 1927. In 1928, she tried to become a delegate to the Republican National Convention but lost to Oscar De Priest. Her feelings toward the Republican Party became more mixed due to the Hoover Administration's stance on civil rights and attempts to promote a "Lily-white" policy in Southern Republican organizations. In 1930, Wells unsuccessfully sought elective office, running as an Independent for a seat in the Illinois Senate, against the Republican Party candidate, Adelbert Roberts.[63][18]

Influence on black feminist activism

Although not a feminist writer herself, Wells-Barnett tried to explain that the defense of white women's honor allowed Southern white men to get away with murder by projecting their own history of sexual violence onto black men. Her call for all races and genders to be accountable for their actions showed African-American women that they can speak out and fight for their rights. By portraying the horrors of lynching, she worked to show that racial and gender discrimination are linked, furthering the black feminist cause.[65]

Autobiography and death

Wells began writing her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928), but never finished the book; it would be posthumously published, edited by her daughter Alfreda Barnett Duster, in 1970, as Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells.[66][67]

Wells died of uremia (kidney failure) in Chicago on March 25, 1931, at the age of 68. She was buried in the Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

Legacy and honors

Since Wells' death, with the rise of mid-20th-century civil rights activism, and the 1971 posthumous publication of her autobiography, interest in her life and legacy has grown. Awards have been established in her name by the National Association of Black Journalists,[68] the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University,[69] the Coordinating Council for Women in History,[70] the Investigative Fund,[71] the University of Louisville,[72] and the New York County Lawyers' Association,[73] among many others. The Ida B. Wells Memorial Foundation and the Ida B. Wells Museum have also been established to protect, preserve and promote Wells' legacy.[74] In her hometown of Holly Springs, Mississippi, there is an Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum in her honor that acts as a cultural center of African-American history.[75]

In 1941, the Public Works Administration (PWA) built a Chicago Housing Authority public housing project in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the south side in Chicago; it was named the Ida B. Wells Homes in her honor. The buildings were demolished in August 2011 due to changing demographics and ideas about such housing.[76]

.jpg)

In 1988, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[77] In August that year, she was also inducted into the Chicago Women's Hall of Fame.[78] Molefi Kete Asante included Wells on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans in 2002.[79] In 2011, Wells was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame for her writings.[80]

On February 1, 1990, the United States Postal Service issued a 25-cent postage stamp in her honor.[81] In 2006, the Harvard Kennedy School commissioned a portrait of Wells.[82] In 2007 the Ida B. Wells Association, was founded by University of Memphis philosophy graduate students to promote discussion of philosophical issues arising from the African American experience and to provide a context in which to mentor undergraduates. The Philosophy Department at the University of Memphis has sponsored the Ida B. Wells conference every year since 2007.[83]

In August 2014, she was the subject of an episode of the BBC Radio 4 programme, Great Lives, in which her work was championed by Baroness Oona King.[84]

On July 16, 2015, which would have been her 153rd birthday, Wells was honored with a Google Doodle.[85][86][87][88][89]

In 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened; it includes a reflection space dedicated to Wells, a selection of quotes by her, and a stone inscribed with her name.[90][91]

On March 8, 2018, The New York Times published a belated obituary for her,[2] in a series marking International Women's Day and entitled "Overlooked" that set out to remedy the fact that since 1851, their obituary pages have been dominated by white men, while significant women — including Wells, and others — had been ignored.[92][93][94]

In July 2018, Chicago's City Council officially renamed Congress Parkway to Ida B. Wells Drive;[95] it is the first downtown Chicago street named for a woman of color.[96]

On February 12, 2019, a blue plaque, provided by the Nubian Jak Community Trust, was unveiled at the Edgbaston Community Centre, Birmingham, England, commemorating Wells’ stay in a house on the site during her speaking tour of the British Isles, in 1893.[97][98][99]

On July 13, 2019, a marker for her was dedicated in Mississippi, on the northeast corner of Holly Springs’ Courthouse Square.[100]

The Extra Mile National Monument in Washington, D.C. selected Wells as one of its 37 honorees. The Extra Mile pays homage to Americans such as Wells who set aside their own self-interest in order to help others and who successfully brought positive social change to the United States.

In 2019, a new middle school in Washington, DC was named in her honor.[101]

On November 7, 2019, a Mississippi Writers Trail historical marker was installed at Rust College in Holly Springs commemorating the legacy of Ida B. Wells.[102]

On May 4, 2020, she was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize special citation, "[f]or her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching."[4][103] The Pulitzer Prize board announced that it would donate at least $50,000 in support of Wells' mission to recipients who would be announced at a later date.[4]

In June 2020, during the George Floyd protests in Tennessee, protesters occupied the area outside the Tennessee State Capitol, re-dubbing it "Ida B. Wells Plaza."[104]

Representation in other media

In 1995, the play In Pursuit of Justice: A One-Woman Play About Ida B. Wells, written by Wendy Jones and starring Janice Jenkins, was produced. It is drawn from historical incidents and speeches from Wells' autobiography, and features fictional letters to a friend. It won four awards from the AUDELCO (Audience Development Committee Inc.), an organization that honors black theatre.[105]

In 1999, a staged reading of the play Iola's Letter, written by Michon Boston, was performed at Howard University in Washington, DC, under the direction of Vera J. Katz, including then-student Chadwick Boseman (Black Panther) among the cast. The play is inspired by the real-life events that compelled a 29-year-old Ida B. Wells to launch an anti-lynching crusade from Memphis in 1892 using her newspaper, Free Speech. Iola's Letter is published in the anthology Strange Fruit: Plays on Lynching by American Women, edited by Judith L. Stephens and Kathy A. Perkins (Indiana University Press, 1998).

Wells' life is the subject of Constant Star (2002), a musical drama by Tazewell Thompson that has been widely performed.[106] The play explores Wells as "a seminal figure in Post-Reconstruction America."[106]

Wells was played by Adilah Barnes in the 2004 film Iron Jawed Angels. The film dramatizes a moment during the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913 when Wells ignored instructions to march with the segregated parade units and crossed the lines to march with the other members of her Illinois chapter.

Selected publications

See also

References

- Giddings, Paula J. "Wells-Barnett, Ida B. 1862–1931", in Patrick L. Mason (ed.), Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, 2nd edn, vol. 4, Macmillan Reference, 2013, pp. 265–67. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Dickerson, Caitlin (March 8, 2018). "Ida B. Wells, Who Took on Racism in the Deep South With Powerful Reporting on Lynchings". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- "Guide to the Ida B. Wells Papers 1884–1976". University of Chicago Library. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- "Announcement of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize Winners". Pulitzer.org. May 4, 2020.

- McMurry, Linda O. "To Keep the Waters Troubled". movies2.nytimes.com. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- Matthews, Dasha (February 21, 2018). "Ida B. Wells: Suffragist, Feminist, and Leader". info.umkc.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Giddings, Paula J. (March 3, 2009). Ida: A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching (Reprint ed.). Amistad. pp. 5–10. ISBN 9780060797362.

- Black, Patti Carr (February 2001). "Ida B. Wells: A Courageous Voice for Civil Rights". Mississippi History Now. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- Bay, Mia (2009). To Tell the Truth Freely:The Life of Ida B. Wells. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8090-9529-2.

- Lynn Yaeger. Vogue, July 16, 2015.

- Franklin, Vincent P. (1995). Living Our Stories, Telling Our Truths: Autobiography and the Making of African American Intellectual Tradition. Oxford University Press

- Fridan, D., & J. Fridan (2000). Ida B. Wells: Mother of the Civil Rights Movement. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 21. ISBN 0-395-89898-6.

- Southwestern Reporter, Volume 4, May 16 – August 1, 1887.

- Southwestern Reporter. West Publishing Company. 1887. p. 5. Retrieved May 12, 2012 – via Internet Archive.

that her persistence was not in good faith to obtain.

- Duster, Alfreda, ed. (1970). Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. xviii. ISBN 978-0-226-89344-0.

- Cardon, Dustin (February 27, 2018). "Ida B. Wells". Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- Duster (1970). Crusade for Justice. p. xviii.

- Giddings, Paula J. (2009). Ida: A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the campaign against lynching. Amistad. ISBN 9780061972942. OCLC 865473600.

- Giddings (2009). Ida: A Sword Among Lions. p. 179. OCLC 865473600.

- Giddings (2009). Ida: A Sword Among Lions. p. 180. OCLC 865473600.

- Gabbidon, Shaun L.; Greene, Helen Taylor; Young, Vernetta D. (2002). African American Classics in Criminology and Criminal Justice. Sage. p. 25. ISBN 9780761924333.

- Giddings (2009). Ida: A Sword Among Lions. p. 183. OCLC 865473600.

- Wells, p. 63.

- Giddings (2009). Ida: A Sword Among Lions. p. 207. OCLC 865473600.

- "The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow . Jim Crow Stories . Ida B. Wells Flees Memphis | PBS". www.thirteen.org. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Baker, Lee D. (February 2012). "Ida B. Wells-Barnett: Fighting and Writing for Justice" (PDF). eJournal USA. U.S. Department of State. 16 (6): 6–8. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- Wells, Ida (1892). "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases – Preface". Digital History. University of Houston. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.

- Curry, Tommy J. (2012). "The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett's Use of T. Thomas Fortune's Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism". Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society. 48 (4): 456–82. doi:10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456.

- Zackodnik, Teresa (June 8, 2005). "Ida B. Wells and "American Atrocities" in Britain". Women's Studies International Forum. 28 (4): 264. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2005.04.012 – via Elsvier.

- "Quakers Against Racism: Catherine Impey and the Anti-Caste Journal". Quakers in the World. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- Bay (2009). To Tell the Truth Freely:The Life of Ida B. Wells. p. 4.

- Duster, Michelle (2010). Ida From Abroad: The Timeless writings of Ida B. Wells from England in 1894. Chicago, Illinois: Benjamin Williams Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-9802398-9-8.

- "Alexander Street Press Authorization". asp6new.alexanderstreet.com. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Wells, p. 125.

- Elliott, p. 242.

- Busby, Margaret, "Ida B. Wells (Barnett)", in Daughters of Africa, London: Jonathan Cape, 1992, p. 150.

- McBride, Jennifer, "Ida B. Wells: Crusade for Justice", Webster University. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- Enright, Mairead (March 8, 2018), "Gender and Legal History in Birmingham and the West Midlands| Ida B. Wells and the Birmingham Connection", University of Birmingham blog.

- Smith, David (April 27, 2018). "Ida B Wells: The Unsung Heroine of the Civil Rights Movement". The Guardian. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "Miss Ida B. Wells About to Marry". Washington Post. June 13, 1895. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- Schechter, Patricia (2001). Ida B. Wells and American Reform: 1880–1930. Capel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 176.

- Tichi, Cecelia (2011). Civic Passions: Seven Who Launched Progressive America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-8078-7191-1.

- Seymour Jr., James B. (2006). Finkelman, Paul (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass. Well-Barnett, Ida. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 333. ISBN 9780195167771.

- Palmer, Stephanie C. (2009). Finkelman, Paul (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Well-Barnett, Ida B. 5. Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780195167795.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. Dusk of Dawn; an Essay toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept, 1940, p. 224.

- Duster (1970), Crusade for Justice, p. 322.

- "National Association of Colored Women's Clubs | Description, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "Honoring Ida B. Wells with Chicago's first monument to an African American Woman". BPI Chicago. October 22, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Wells, Ida B. (1970). Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. ISBN 9780226189185.

- Pinar, William F. (2009). The Worldliness of a Cosmopolitan Education: Passionate Lives in Public Service. Routledge. pp. 77–79. ISBN 9781135844851.

- Davies, Carole Boyce (2008). Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 977. ISBN 9781851097005.

- Schechter, Patricia (2001). Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880–1930. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Ella Wagner; et al., eds. (March 14, 2019). "Truth-Telling: Frances Willard and Ida B. Wells, Introduction". Frances Willard House Museum. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Duster (1970). Crusade for Justice. Chicago. Chapters 18, 19 and 20.

- Grossman, Ron (June 23, 2013). "Illinois Women Win the Right To Vote". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- Schechter, Patricia (2001). Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Schechter, Patricia (2001). Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Boissoneault, Lorraine (January 21, 2017). "The Original Women's March on Washington and the Suffragists Who Paved the Way". Smithsonian. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- Bay (2009). To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B Wells. p. 290.

- Flexner, Eleanor (1996). Century of Struggle: the Women's Rights Movement in the United States. Cambridge MA and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 318. ISBN 9780674106536.

- Stillion Southard, Belinda A. (2011). Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913-1920. Texas A&M University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-60344-281-7.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Rust, Randal. "Ida B. Wells-Barnett". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- Audrey Thomas McCluskey, A Forgotten Sisterhood: Pioneering Black Women Educations and Activists in the Jim Crow SOuth (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014) p. 8

- Stansell, Christine (2010). The Feminist Promise. New York: Modern Library. p. 126.

- Black, Patti Carr (February 2001), "Ida B. Wells: A Courageous Voice for Civil Rights", Mississippi History Now.

- "Alfreda Wells discusses her mother, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her book 'Crusade for Justice'", Studs Terkel Radio Archive, broadcast September 3, 1971.

- "Ida B. Wells Award". National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ). Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Ida B. Wells Award". Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Ida B. Wells Graduate Student Fellowship". Coordinating Council for Women in History. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Ida B. Wells Fellowship". Investigative Fund. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- "Ida B. Wells Award – An award for Diligence and Achievement". University of Louisville. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Ida B. Wells-Barnett Justice Award". New York County Lawyers Association. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Ida B. Wells Memorial Foundation and Museum". Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum". Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- "Ida B. Wells Homes Chicago, Illinois". Wikimapia.org. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- "Ida B. Wells-Barnett", National Women's Hall of Fame.

- Burleigh, Nina (August 21, 1988). "Hall Of Fame Will Induct 10". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. p. 98. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- "Ida B. Wells". Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- "Women Subjects on United States Postage Stamps" (PDF). United States Postal Service. p. 3. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- "Harvard Kennedy School portrait of Ida B. Wells". Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "University of Memphis Ida B. Wells Philosophy Conference". Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- "BBC Radio 4 - Great Lives, Series 34, Baroness Oona King on Ida B Wells". BBC. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- "Ida B. Wells' 153rd Birthday", DoodlesArchive, Google.

- Jalabi, Raya (July 16, 2015), "Ida B Wells, African American activist, honored by Google", The Guardian.

- Berenson, Tessa (July 16, 2015), "Today's Google Doodle Celebrates Journalist Ida B. Wells' Birthday", TIME.

- Cavna, Michael (July 16, 2015), "Here's why Google Doodle salutes fearless, peerless word-warrior Ida B. Wells", The Washington Post.

- Root, Kirsten (July 16, 2015), "Who was Ida B. Wells, the woman honored in a Google Doodle on Thursday?", Women In The World.

- Brown, DeNeen L. (April 26, 2018). "Ida B. Wells: Lynching museum, memorial honors woman who fought lynching". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- "HISTORY: Movement to Honor Anti-Lynching Crusader and Journalist Ida B. Wells in Chicago is Gaining Momentum, and is 'Long Overdue'". Good Black News. Goodblacknews.org. July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- Padnani, Amisha, and Jessica Bennett (March 8, 2018), "Women We Overlooked in 167 Years of New York Times Obituaries", The New York Times on, via Bunk.

- Danielle, Britni (March 8, 2018), "The New York Times Is Finally Giving Ida B. Wells Her Due", Essence.

- Linton, Caroline (March 8, 2018), "'We want to address these inequities of our time': NYT starts new series featuring overlooked obituaries2, CBS News.

- Mohan, Pavithra (August 8, 2018), "How these women raised $42K in a day for an Ida B. Wells monument", Fast Company.

- Byrne, Gregory Pratt, John (July 25, 2018). "Ida B. Wells gets her street—City Council approves renaming Congress in her honor". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- "Heritage Plaque to Ida B. Wells", AntiSlavery Usable Past Project (ASUP), January 16, 2019.

- "Birmingham blue plaque unveiled to commemorate civil rights activist Ida B. Wells", I Am Birmingham, February 14, 2019.

- Washington, Linn (February 14, 2019), "Ida Wells Barnett honored in Birmingham, England", The Chicago Crusader.

- Klinger, Jerry (July 15, 2019). "Jewish group helps dedicate Ida Wells- Barnett marker". San Diego Jewish World. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- Collins, Sam P. K. (March 26, 2019). "New D.C. Middle School to be Renamed for Ida B. Wells". Washington Informer. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- "Mississippi Writers Trail". Mississippi Arts Commission. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Greene, Morgan (May 4, 2020). "Ida B. Wells receives Pulitzer Prize citation: 'The only thing she really had was the truth'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Hineman, Brinley (June 12, 2020). "Protesters hang an 'Ida B. Wells Plaza' banner where a statue of Edward Carmack stood before it was toppled by protesters". The Tennessean. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Viagas, Robert, "Audelco Award Winners", Playbill, December 1, 1995.

- Gates, Anita (July 23, 2006). "Constant Star – Review". The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

Bibliography

- Bay, Mia (2009). To Tell the Truth Freely: the life of Ida B. Wells. New York: Hill & Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-9529-2.

- Buechler, S. M. (1951). Women's Movements in The United States, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Campbell, Karlyn Kohrs (1986). "Style and content in the rhetoric of early Afro‐American feminists". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 72 (4): 434–45. doi:10.1080/00335638609383786.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curry, Tommy J. (Fall 2012). "The fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett's use of T. Thomas Fortune's philosophy of social agitation as a prolegomenon to militant civil rights activism". Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society. 48 (4): 456–82. doi:10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456. JSTOR 10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, E. L. (1922). The Story of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, Chicago: Illinois Federation of Colored Women's Clubs.

- Effinger-Crichlow, Marta (2014). Staging Migrations Toward an American West: From Ida B. Wells to Rhodessa Jones. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

- Elliott, Mark (2006). Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgée and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War to Plessey v. Ferguson. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gere, Anne R.; Robbins, Sarah R. (Spring 1996). "Gendered literacy in black and white: turn-of-the-century African-American and European-American club women's printed texts". Signs. 21 (3): 643–78. doi:10.1086/495101. JSTOR 3175174.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Giddings, P. J. (2008). Ida, A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching (New York: Amistad/HarperCollins, 2008, ISBN 0060797363).

- Hendricks, W. A. (1998). Gender, Race, and Politics in the Midwest, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- McCammon, Holly J. (2003). ""Out of the parlors and into the streets": the changing tactical repertoire of the U.S. women' suffrage movements". Social Forces. 81 (3): 787–818. doi:10.1353/sof.2003.0037.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McMurry, Linda O. (1998). To Keep the Waters Troubled, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Parker, Maegan (2008). "Desiring citizenship: a rhetorical analysis of the Wells/Willard controversy". Women's Studies in Communication. 31 (1): 56–78. doi:10.1080/07491409.2008.10162522.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Royster, J. J. (1997). Southern Horrors and Other Writings, New York: Bedford.

- Wells, Ida B. (1970). Alfreda M. Duster, ed. Crusade For Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Negro American Biographies and Autobiographies Series. John Hope Franklin, Series Editor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-89342-1. http://lccn.loc.gov/73108837. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- Zackodnik, Teresa (July–August 2005). "Ida B. Wells and 'American Atrocities' in Britain". Women's Studies International Forum. 28 (4): 259–73. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2005.04.012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

| Library resources about Ida B. Wells |

| By Ida B. Wells |

|---|

- Works by Ida B. Wells at Project Gutenberg

- The Memphis Diary of Ida B. Wells, memoirs, travel notes and selected articles (Beacon Press, 1995)

- Ida B. Wells, "Lynch Law" (1893), History Is a Weapon Website

- "Ida B. Wells – Illinois During the Gilded Age, 1866–1896". The Northern Illinois University, Illinois Historical Digitization Projects at Northern Illinois University Libraries. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- Baker, Lee D. "Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931) and Her Passion for Justice". Duke University. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- Shay, Alison. "Remembering Ida B. Wells-Barnett". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- Davidson, James West. 'They say': Ida B. Wells and the Reconstruction of Race. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Dickerson, Caitlyn, "Ida B. Wells, 1862–1931", The New York Times, March 8, 2018.

- Dray, Philip, Yours for Justice, Ida B. Wells: The Daring Life of a Crusading Journalist, Peachtree, 2008.

- Lutes, Jean Marie (2007). Front Page Girls: Women Journalists in American Culture and Fiction, 1880–1930. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801474125. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Royster, Jacqueline Jones, ed., Southern horrors and other writings: The anti-lynching campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892–1900 Boston: Bedford Books, 1997.

- Schechter, Patricia A. Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880–1930. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Silkey, Sarah L. Black Woman Reformer: Ida B. Wells, Lynching, and Transatlantic Activism. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2015.

External links

- Works by Ida B. Wells at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ida B. Wells at Internet Archive

- Works by Ida B. Wells at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Interview with Linda McMurry on To Keep the Waters Troubled: The Life of Ida B. Wells, Booknotes, September 26, 1999

- Ida B. Wells at Find a Grave

- Norwood, Arlisha. "Ida B. Wells-Barnett". National Women's History Museum. 2017.

- Ida B. Wells episode, Great Lives, BBC Radio 4 (mp3)

- Guide to the Ida B. Wells Papers 1884-1976 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center