Face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, face masks have been employed as a public and personal health control measure against the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Their use is intended as personal protection to prevent infection and as source control to limit transmission of the virus in a community or healthcare setting. The use of masks has received varying recommendations from different public health agencies and governments. The World Health Organization and other public health organisations agree that masks can limit the spread of respiratory viral diseases such as COVID-19.[1][2][3] However, the topic has been a subject of debate,[4] with some public health agencies and governments initially disagreeing on a protocol for wearing face masks.

As of early May 2020, 88% of the world's population lives in countries that recommend or mandate the use of masks in public; more than 75 countries have mandated the use of masks.[5] Debates have emerged regarding whether masks should be worn even when social distancing at 2 meters (6 feet),[6][7][8] and whether they should be worn during exercise.[9] Additionally, public health agencies of some countries and territories have changed their recommendations regarding face masks over time.[10] Face masks have been a subject of shortages, and not all have been certified. Moreover, substandard masks were reported on the market with significantly reduced performance.[11]

There are different types of face masks including:

- cloth face masks

- medical or surgical masks

- filtering facepiece respirators such as N95 masks, N99 masks, and FFP masks

Face shields, medical goggles, and other types of personal protective equipment are sometimes used together with face masks.

Types of masks

Cloth masks

A cloth face mask is a mask made of a common textile, usually cotton, worn over the mouth and nose. Although they are less effective than medical-grade masks, many health authorities recommend that the general public use them because medical-grade masks are in short supply.[14][15]

There were calls for research into the effectiveness of improvised masks even before the emergence of COVID-19, motivated also by past epidemics and modelling of likely mask shortages. However, little research has been done. There are no studies of the use of cloth masks by the general public, one study on the use of cloth masks in hospitals (by healthcare workers, not patients), and many controlled-setting/lab studies of cloth masks' effects on aerosols as of May 2020.[16]

Cloth masks are low-cost and reusable. They vary widely in effectiveness depending on material, fit/seal, and number of layers, among other factors. Unlike disposable masks, there are no legal standards for cloth masks. Fit is important (as with disposable masks). Measures to improve fit, such as an outer layer made from sheer nylon stockings or sheer tights around the head, reduce leakage.[16]

Improvised cloth masks seem to be worse than standard commercial disposable masks, but better than nothing. There is, however, little good evidence on them. A single study gives evidence that an improvised mask was better than nothing, but not as good as soft electret-filter surgical mask, for protecting health care workers simulating treating a simulated infected patient, regardless of whether "patient" or carers wore the mask.[16] Another study had volunteers wear masks they made themselves, to a pattern like that of a standard surgical mask, but with ties rather than earloops,[17] from cotton T-shirts, and found that the number of microscopic particles that leaked inside the homemade masks was twice the number that leaked into the commercial masks, and that the homemade mask let three times as many microorganisms expelled by the wearer escape (median averages). There is limited evidence that cloth masks can significantly reduce droplet dispersal.[16]

Cloth masks are commonly made with one layer, two layers, or two layers with a pocket for a removable-filter interlayer[16] (disposable surgical masks also have three layers, with the filter layer midmost). The CDC recommends more than one layer.[19] There is no research on the usefulness of a filter interlayer, as of May 2020. There were until recently no non-disposable materials designed for making masks (see end of paragraph). Common household fabrics which could be used (turned to a new use) as mask materials have been tested.[20][21][22][23] Cloth materials vary widely in filtration efficiency. Some cotton and polyester household fabrics have been found to compare with disposable surgical masks for dry particle filtering. Cotton T-shirt material, pillowcase material, and 70% cotton/30% polyester sweatshirt material are among the common materials that performed well in lab tests, with T-shirts preferred to pillowcases because it was thought that it would probably fit better. Teatowels and vacuum-cleaner bags were effective at filtering, but had a very high air resistance, so were not recommended. Scarves filtered poorly. Surgical sterilisation wrap, a polypropylene non-woven fabric made for wrapping sterilized things to keep them sterile, is designed to filter germs from the air. Using surgical sterilisation wrap to make masks, or as a filter interlayer in cloth masks, has been suggested. There are, however, no tests on using surgical sterilisation wrap for masks, as of May 2020.[16]

Other suggested materials for filter interlayers include air filter materials used in ventilation, heating, and air conditioning, some of which are similar to rigid electret masks in the size ranges of particles they filter. Electrostatic cotton and non-woven, meltblown fabric are the conventional materials used in disposible masks, but are not readily available during the COVID-19 epidemic. A new type of filter, a washable electrostatic cotton filter, has been reported since the start of the pandemic; it is said to withstand repeated washing and folding.[16] It is made of electrospun nanofibers; flanking insulating blocks lay these into quasi-aligned nonwoven sheets, which are layered criss-cross to make a meshlike multilayer mask.[24][25] There is a need for research comparing how well these materials work.[16][26]

Decontamination and re-use

There is no research on decontaminating and reusing cloth masks, as of May 2020.[16] The CDC recommends doffing the mask by handling only the ear loops or ties, placing it directly in a washing machine, and immediately washing one's hands in soap and water for at least 20 seconds. They also recommend washing one's hands before donning the mask and again immediately after one touches it.[27]

There is no information on reusing a interlayer filter, and disposing of it after a single use may be desirable.[16]

Surgical masks

A surgical mask is a loose-fitting, disposable device that creates a physical barrier between the mouth and nose of the wearer and potential contaminants in the immediate environment. If worn properly, a surgical mask is meant to help block large-particle droplets, splashes, sprays, or splatter that may contain viruses and bacteria, keeping it from reaching the wearer's mouth and nose. Surgical masks may also help reduce exposure of the wearer's saliva and respiratory secretions to others.[28]

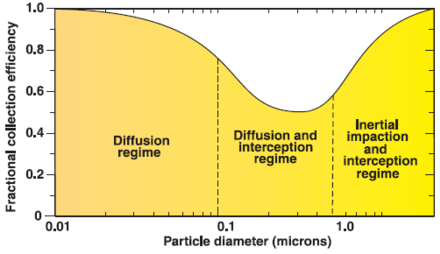

Certified medical masks are made of non-woven material. They are mostly multi-layer. Filter material may be made of microfibers with an electrostatic charge; that is, the fibers are electrets. An electret filter increases the chances that smaller particles will veer and hit a fiber, rather than going straight through (electrostatic capture).[12][29][30] While there is some development work on making electret filtering materials that can stand being washed and reused,[31] current commercially-produced electret filters are ruined by many forms of disinfection, including washing with soap and water or alcohol, which destroys the electric charge.[32] During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health authorities issued guidelines on how to save, disinfect and reuse electret-filter masks without damaging the filtration efficiency.[33][32] Standard disposible surgical masks are not designed to be washed.

A surgical mask, by design, does not filter or block very small particles in the air that may be transmitted by coughs, sneezes, or certain medical procedures. Surgical masks also do not provide complete protection from germs and other contaminants because of the loose fit between the surface of the face mask and the face.[28] However, in practice, with respect to some infections like influenza, surgical masks appear as effective as respirators (such as N95 or FFP masks).[34] Surgical masks may be labeled as surgical, isolation, dental, or medical procedure masks.[28] Surgical masks are made of a nonwoven fabric created using a melt blowing process.[35][36]

Surgical masks made to different standards in different parts of the world have different ranges of particles which they filter. For example, the People's Republic of China regulates two types of such masks: single-use medical masks (Chinese standard YY/T 0969) and surgical masks (YY 0469). The latter ones are required to filter bacteria-sized particles (BFE ≥ 95%) and some virus-sized particles (PFE ≥ 30%), while the former ones are required to only filter bacteria-sized particles.[37][38][39]

Disposable filtering facepiece respirators

An N95 mask is a particulate-filtering facepiece respirator that meets the N95 air filtration rating of the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, meaning that it filters at least 95 percent of airborne particles, while not resistant to oil like the P95. It is the most common particulate-filtering facepiece respirator.[40] It is an example of a mechanical filter respirator, which provides protection against particulates, but not gases or vapors.[41] Like the middle layer of surgical masks, the N95 mask is made of four layers[16] of melt-blown nonwoven polypropylene fabric.[42][43] The corresponding face mask used in the European Union is the FFP2 respirator.[44][45]

Hard electret-filter masks like N95 and FFP masks must fit the face to provide full protection. Untrained users often get a reasonable fit, but fewer than one in four gets a perfect fit. Fit testing is thus standard. A line of vaseline on the edge of the mask[46] has been shown to reduce edge leakage[16] in lab tests using manikins that simulate breathing.[46]

In the COVID-19 pandemic, there were shortages of filtering facepiece respirators, so that they had to be used for extended periods, and/or disinfected and reused. During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health authorities issued guidelines on how to save, disinfect and reuse masks, as some disinfection methods damaged the filtration efficiency.[33][32] Some hospitals stockpiled used masks as a precaution,[47] and some had to reuse masks.

Elastomeric respirators

.jpg)

Elastomeric respirators are reusable devices with exchangeable cartridge filters that offer comparable protection to N95 masks.[48] They were used as a substitute for N95 masks among shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic.[49]

The filters must be replaced when soiled, contaminated, or clogged. These components may be hard to find amidst shortages; the filters may thus be sterilized, in a way that does not harm the filter, and re-used. In medical use, they must be cleaned and disinfected, as some germs can survive on them for weeks.[49]

Full-face versions of elastomeric respirators seal better and protect the eyes. If they have exhalation valves, then they are counterrecommended in settings where the unfiltered exhaled air might infect others (for instance, surgery). Fitting and inspection is essential to effectiveness.[49]

Powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs)

PAPRs are expensive masks with a battery-powered blower that blows air through a filter to the wearer. Because they create positive pressure, they need not be tightly-fitted.[50] PAPRs typically do not filter exhaust from the wearer.[51] They are not generally designed for healthcare use, as of 2017.[52]

Novel face masks (research and development)

On 15 April 2020 scientists claimed to have developed a biodegradable material for face masks which is effective at removing particles smaller than 100 nanometres including viruses and has a high breathability.[53][54] Two Israeli companies reportedly have developed antiviral face masks – one of which is infused with antiviral copper oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles, the other is made out of cotton embedded with accelerated copper oxide particles and a nanofiber textile.[55][56][57] Other Israeli researchers have developed a 3D-printed nanoscale fiber sticker coated with antiseptics which can be attached to a traditional mask for extra protection.[57] Other reseachers report that laser-induced graphene may be used to add self-cleaning and photothermal properties to face masks.[57] In March 2020, Huang Jiaxing became the first scientist to receive a $200,000 grant by the United States' National Science Foundation to develop a chemical which can be safely built into common face masks to make them protect against SARS-CoV-2 and self-sanitize passing droplets.[57][58]

Face shields

Face shields protect against splash and splatter. Cough simulation experiments show that they protect[16] the wearer[59] against large droplets immediately after the cough, but are less effective against smaller aerosols, which can remain airborne for extended periods and can easily flow around a face shield to be inhaled.

Because they lack a peripheral seal, face shields are used with nose-mouth masks, and to protect nose-mouth masks, but use of face shields alone is not recommended for healthcare workers.[16]

Recommendations

Surgical masks are recommended for those who may be infected,[60][61][62] as wearing a mask can limit the volume and travel distance of expiratory droplets dispersed when talking, sneezing, and coughing.[63] Masks have also been recommended for use by those who are taking care of someone who may have the disease.[62] The WHO has recommended the wearing of masks by healthy people only if they are at high risk, such as those who are caring for a person with COVID-19, though they also acknowledge that wearing masks may help people avoid touching their face.[62] Several countries have started to encourage the use of face masks by members of the public.[64]

As of May 2020, 88% of the world's population lived in countries where their government and leading disease experts recommended or mandated the use of masks in public places to limit the spread of COVID-19.[5]

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO), in its updated advice dated 5 June 2020, recommends that the general public should wear non-medical fabric masks where there is known or suspected widespread transmission and where physical distancing is not possible, and that vulnerable people (aged over 60 or with underlying health risks) and people with any symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 as well as caregivers and healthcare workers should wear medical masks.[65] The stated purpose of mask usage is to prevent the wearer transmitting the virus to others (source control) or to offer protection to healthy wearers against infection (prevention).[65]

The WHO advises that non-medical fabric masks should comprise a minimum of three layers,[66] suggesting an inner layer made of absorbent material (such as cotton), a middle layer made of non-woven material (such as polypropylene) which may enhance filtration or retain droplets, and an outer layer made of non-absorbent material (such as polyester or its blends) which may limit external contamination from penetration.[67]

Previously, early in the outbreak, the WHO had only recommended medical masks for people with suspected infection and respiratory symptoms, their caregivers and those sharing living space, and healthcare workers.[68][69] In a 6 April advice, the WHO recognized that wearing a medical mask can limit the spread of certain respiratory viral diseases including COVID-19, but believed that the use of a mask alone is not sufficient to provide an adequate level of protection and that other measures (such as hand hygiene) should be adopted.[70] In the scope of the community setting, the WHO stated that medical masks should be reserved for healthcare workers, except for people with symptoms, claiming that medical masks would create a false sense of security and neglect of other measures.[70] The WHO advice for people to wear masks only if they had symptoms was criticized, as experts and researchers have pointed out the asymptomatic transmission of the virus.[71][72] The WHO revised its mask guidance in June, with its officials acknowledging that studies have indicated asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic spread but that not much is known.[73]

The WHO had early suggested that mask usage possibly leads to neglect of other essential health measures such as hand hygiene practices, but, according to Marteau et al. (27 July 2020), available evidence does not support that masking adversely affects hand hygiene.[74] Dame Theresa Marteau, one of the researchers, remarked that "The concept of risk compensation, rather than risk compensation itself, seems the greater threat to public health through delaying potentially effective interventions that can help prevent the spread of disease."[75]

Regarding the use of non-medical fabric masks in the general population, the WHO has stated that high-quality evidence for its widespread use is limited, but advises governments to encourage its use as physical distancing may not be possible in some settings, there is some evidence for asymptomatic transmission, and masks could be helpful to provide a barrier to limit the spread of potentially infectious droplets.[76]

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), since 3 April 2020, recommends persons wear a cloth face covering in public.[78] In its latest considerations (updated 16 July 2020), the "CDC recommends that people wear cloth face coverings in public settings and when around people who don't live in your household, especially when other social distancing measures are difficult to maintain. Cloth face coverings may help prevent people who have COVID-19 from spreading the virus to others. Cloth face coverings are most likely to reduce the spread of COVID-19 when they are widely used by people in public settings."[79]

The CDC states that healthcare personnel should wear a NIOSH-approved N95 (or equivalent or higher-level) respirator or a face mask (if a respirator is not available) with a face shield or goggles as part of their personal protective equipment, while patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection should wear a face mask or cloth face covering during transport.[80] As crisis strategy for known shortages of N95 respirators in healthcare settings, among other sequential measures, the CDC suggests use of respirators beyond the manufacturer-designated shelf life, use of respirators approved under standards used in other countries that are similar to NIOSH-approved respirators, limited re-use of respirators, use of additional respirators beyond the manufacturer-designated shelf life that have not been evaluated by NIOSH, and prioritizing the use of respirators and face masks by activity type.[81]

Early in the pandemic, the CDC said that it "[did] not currently recommend the use of face masks for the general public."[82][83] However, on 3 April 2020, the CDC changed its advice to recommend that people wear cloth face coverings "in public settings when around people outside their household, especially when social distancing measures are difficult to maintain."[84] In response to an inquiry by NPR, the CDC said that this change in guidelines was due to the increasing and widespread transmission of the virus, citing studies published in February and March showing presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission.[85] In an interview with KRMG on 28 July 2020, the CDC director Robert R. Redfield explained that they assumed that the disease was a symptomatic illness when they originally looked at masks, not understanding at the time how much of the viral infection was asymptomatic or presymptomatic, but came to understand the critical role of face coverings for source control once they understood that.[86]

Larry Gostin, a professor of public health law, said that initial CDC and WHO guidance had given the public the wrong impression that mask do not work, even though scientific evidence to the contrary was already available.[85] The confusing changing advice from discouraging to recommending public masking has led to decreasing public trust in the CDC.[72][87] In June 2020 Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, admitted that the delay in recommending general mask use was motivated by a desire to conserve dwindling supplies for medical professionals.[88]

In an interview with JAMA on 14 July 2020, Redfield said that "The data is clearly there that masking works. [...] Masking is not a political issue. It is a public health issue. It really is a personal responsibility for all of us."[89] He and two other CDC officials explained in a JAMA editorial, published on the same day, that "Covering mouths and noses with filtering materials serves 2 purposes: personal protection against inhalation of harmful pathogens and particulates, and source control to prevent exposing others to infectious microbes that may be expelled during respiration. When asked to wear face coverings, many people think in terms of personal protection. But face coverings are also widely and routinely used as source control."[90] In regards to the changes in CDC recommendations towards universal masking, they clarified that "Early in the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that anyone symptomatic for suspected coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) should wear a face covering during transport to medical care and prior to isolation to reduce the spread of respiratory droplets. After emerging data documented transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from persons without symptoms, the recommendation was expanded to the general community [...] Now, there is ample evidence that persons without symptoms spread infection and may be the critical driver needed to maintain epidemic momentum."[90]

China and Asia

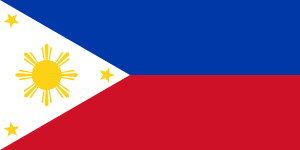

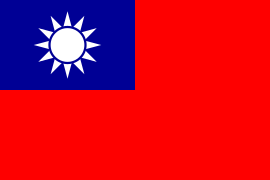

China has specifically recommended the use of disposable medical masks by the public, including its healthy members,[91][92] particularly when coming into close contact (1 metre (3 ft) or less) with other people.[93] Hong Kong recommends wearing a surgical mask when taking public transport or in crowded places.[94][95] Thailand's health officials are encouraging people to make cloth face masks at home and wash them daily.[96] The Republic of China (Taiwan), South Korean, and Japanese governments have also recommended the use of face masks in public.

In March 2020, when asked about the mistakes that other countries were making in the pandemic, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention director-general George Fu Gao said:

"The big mistake in the U.S. and Europe, in my opinion, is that people aren't wearing masks. This virus is transmitted by droplets and close contact. Droplets play a very important role − you've got to wear a mask, because when you speak, there are always droplets coming out of your mouth. Many people have asymptomatic or presymptomatic infections. If they are wearing face masks, it can prevent droplets that carry the virus from escaping and infecting others."[97]

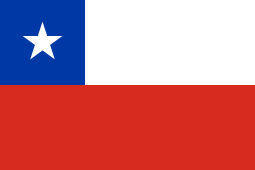

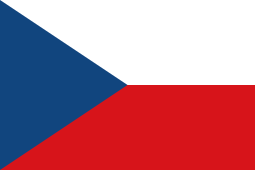

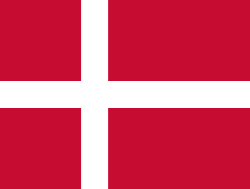

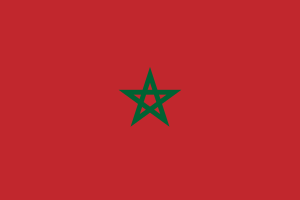

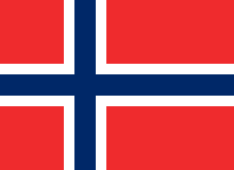

Europe

Most countries in Europe have introduced mandatory face mask rules for public places,[98][99] but Nordic countries have been an exception to this.[99] Denmark (on 31 July 2020),[100][101] Finland (on 13 August 2020),[102] and Norway (on 14 August 2020)[99] eventually started recommending public masking, while Sweden maintains its position to not recommend masks at all.[99]

In the Nordic countries, the main reasoning against masks recommendations given by officials is that public masking is deemed an unnecessary precaution when infection levels remain low.[103] Earlier, in June 2020, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health said that the wearing of face masks by asymptomatic individuals was not to be recommended due to the low prevalence of COVID-19 in the country, but noted that it should be reconsidered if cases rise.[104] Similarly, on 30 July 2020, the Danish Health Authority director Soren Brostrom said that face covers did not make sense in the current situation with low infection levels, but that they needed to evaluate whether it could make sense in the long term.[100][105]

Rationale for wearing masks

.jpg)

The National Health Commission of China cited the following reasons for the wearing of masks by the public, including healthy individuals:

- Asymptomatic transmission. Many people can be infected without symptoms or only with mild symptoms.[107]

- Difficulty or impossibility of appropriate social distancing in many public places at all times.[107]

- Cost-benefit mismatch. If only the infected individuals wear a mask, they would possibly have a negative incentive to do so. An infected individual might get nothing positive, but only bear the costs such as inconvenience, purchasing expenses, and even prejudice.[107]

- There is no shortage of masks in China. The country has the production capacity to meet the demand on masks.[107]

Yuen Kwok-yung, a microbiologist from the University of Hong Kong, cites a high viral load in infected people and transmission by asymptomatic carriers as the reasons why even seemingly healthy individuals should wear a mask.[108][109]

Wang Linfa, an infectious disease expert who heads a joint Duke University and National University of Singapore research team, stated that masking is about "preventing the spread of disease rather than preventing getting the disease", remarking that the point is to cover the faces of people who are infected but do not know it, so it is imperative for everyone to wear one in public.[110] Cheng, Lam, and Leung (16 April 2020) in The Lancet said that a public health rationale for mass masking is source control to protect others from respiratory droplets and underscored the importance of this approach due to asymptomatic transmission.[111]

In a perspective, Gandhi, Beyrer, and Goosby (31 July 2020) posit that masking reduces the inoculum of the virus for the wearer and thus helps lower the severity of infection.[112]

According to Stephen Griffin, a virologist at the University of Leeds, "Wearing a mask can reduce the propensity for people to touch their faces, which is a major source of infection without proper hand hygiene."[113]

Greenhalgh et al. (27 April 2020) argue for the precautionary principle as a reason for policies to encourage the wearing of face masks in public.[114]

Efficacy studies for COVID-19

A WHO-funded systematic review by Chu et al. (27 June 2020) published in The Lancet found that the usage of face mask could result in a large risk reduction of infection with epidemic-causative betacoronaviruses, in which N95 or similar respirators accounted for a larger risk reduction than disposable surgical or other similar masks.[115] Masks were found to be protective for both healthcare workers and people in communities exposed to infection; evidence supports masking in both healthcare and non-healthcare settings, with no striking differences detected in the effectiveness of masks between the settings.[115] Eye protection (e.g., goggles and face shields) was also associated with a lower risk of infection.[115]

A study by Chan et al. (30 May 2020), using SARS-CoV-2-challenged Syrian hamster models and non-infected hamsters placed in closed units with unidirectional airflow to test the effect of surgical mask partitions, concluded that SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted by respiratory droplets or airborne droplet nuclei and that such transmission could be reduced by usage of surgical masks, especially when worn by infected individuals.[116] Yuen Kwok-yung, one of the researchers, said that "The findings implied to the world and the public is that the effectiveness of mask-wearing against the coronavirus pandemic is huge,"[117][118][119] but cautioned that a risk of infection still remains.[117]

A study surveying families in Beijing, China concluded that the wearing of face masks by infected individuals at home before symptom onset was effective in reducing the risk of spreading the disease to family members, but that it did little to provide additional protection after symptoms start appearing.[120]

Primary research from countries such as Germany and Thailand have shown significant decreases in case rates with widespread mask compliance, without, however, controlling for other measures such as social distancing.[121][122]

A report from the United States Department of Health and Human Services found that 139 clients exposed to two symptomatic hair stylists with confirmed COVID-19—with both the clients and stylists wearing face coverings—resulted in no symptomatic cases reported among all clients and no positive tests among those who volunteered to be tested.[123] This case was highlighted when the CDC reiterated that Americans should wear masks.[124]

Shortages of face masks

Early epidemic in mainland China

.jpg)

As the epidemic accelerated, the mainland market in China saw a shortage of face masks due to increased public demand.[125] In Shanghai, customers had to queue for nearly an hour to buy a pack of face masks; stocks were sold out in another in half an hour.[126] Hoarding and price gouging drove up prices, so the market regulator said it would crack down on such acts.[127][128] In January 2020, price controls were imposed on all face masks on Taobao and Tmall.[129] Other Chinese e-commerce platforms – JD.com,[130] Suning.com,[131] Pinduoduo[132] – did likewise; third-party vendors would be subject to price caps, with violators subject to sanctions.

By March, China had quadrupled its production capacity to 100 million masks per day.[107]

National stocks and shortages

At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States, the U.S.'s Strategic National Stockpile contained just 12 million N95 respirators, far fewer than estimates of the amount required.[133] Millions of N95s and other supplies were purchased from 2005 to 2007 using congressional supplemental funding, but 85 million N95s were distributed to combat the 2009 swine flu pandemic, and Congress did not make the necessary appropriations to replenish stocks.[133] The Stockpile's primary focus has also primarily been on biodefense (defense against a terrorist or weapon of mass destruction attack) and response to natural disaster, with infectious disease a secondary focus.[133] By 1 April 2020, the Stockpile was nearly emptied of protective gear.[134] In January and February 2020, U.S. manufacturers, with the encouragement of the Trump administration, shipped millions of face masks and other personal protective equipment to the PRC, a decision that subsequently prompted criticism given the mask shortage that the U.S. faced during the pandemic.[135]

In France, 2009 H1N1-related spending rose to €382 million, mainly on supplies and vaccines, which was later criticized.[136][137] It was decided in 2011 to not replenish its stocks and rely more on supply from China and just-in-time logistics.[136] In 2010, its stock included 1 billion surgical masks and 600 million FFP2 masks; in early 2020, it was 150 million and zero respectively.[136] While stocks were progressively reduced, a 2013 rationale stated the aim to reduce costs of acquisition and storage, now distributing this effort to all private enterprises as an optional best practice to ensure their workers' protection.[136] This was especially relevant to FFP2 masks, more costly to acquire and store.[136][138] As the COVID-19 pandemic in France took an increasing toll on medical supplies, masks and PPE supplies ran low, causing national outrage. France needs 40 millions masks per week, according to French president Emmanuel Macron.[139] France instructed its few remaining mask-producing factories to work 24/7 shifts, and to ramp up national production to 40 million masks per month.[139] French lawmakers opened an inquiry on the past management of these strategic stocks.[140] The mask shortage has been called a "scandal d'État" (State scandal).[141]

In late-March/early-April 2020, as Western countries were in turn dependent on China for supplies of masks and other equipment, China was seen as making soft-power play to influence world opinion.[142][143] However, a batch of masks purchased by the Netherlands was reportedly rejected as being sub-standard. The Dutch health ministry issued a recall of 600,000 face masks from a Chinese supplier on 21 March which did not fit properly and whose filters did not work as intended despite them having a quality certificate.[142][143] The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded that the customer should "double-check the instructions to make sure that you ordered, paid for and distributed the right ones. Do not use non-surgical masks for surgical purposes".[143] Eight million of 11 million masks delivered to Canada in May also failed to meet standards.[144][145]

N95 and FFP masks

N95 and FFP masks were in short supply and high demand during the COVID-19 pandemic.[146][136] Production of N95 masks was limited due to constraints on the supply of nonwoven polypropylene fabric (which is used as the primary filter), as well as the cessation of exports from China.[42][147] China controls 50 percent of global production of masks, and facing its own coronavirus epidemic, dedicated all its production for domestic use, only allowing exports through government-allocated humanitarian assistance.[42]

In March 2020, US President Donald Trump applied the Defense Production Act against the American company 3M, which allows the Federal Emergency Management Agency to obtain N95 respirators from 3M.[148][149] White House trade adviser Peter Navarro stated that there were concerns that 3M products were not making their way to the US.[148] 3M replied that it has not changed the prices it charges, and was unable to control the prices its dealers or retailers charge.[148]

In early April 2020, Berlin politician Andreas Geisel alleged that a shipment of 200,000 N95 masks that it had ordered from American producer 3M's China facility were intercepted in Bangkok and diverted to the United States. Berlin Police president Barbara Slowik stated that she believed "this is related to the US government's export ban."[150] 3M said they had no knowledge of the shipment, stating "We know nothing of an order from the Berlin police for 3M masks that come from China," and the US government denied that any confiscation had taken place and said that they use appropriate channels for all their purchases.[150][151]

Berlin police later confirmed that the shipment was not seized by US authorities, but was said to have simply been bought at a better price, widely believed to be from a German dealer or China. This revelation outraged the Berlin opposition, whose CDU parliamentary group leader Burkard Dregger accused Geisel of "deliberately misleading Berliners" in order "to cover up its own inability to obtain protective equipment". FDP interior expert Marcel Luthe said "Big names in international politics like Berlin's senator Geisel are blaming others and telling US piracy to serve anti-American clichés."[152] Politico Europe reported that "the Berliners are taking a page straight out of the Trump playbook and not letting facts get in the way of a good story."[153] The Guardian also reported that "There is no solid proof Trump [nor any other American official] approved the [German] heist".[154]

Jared Moskowitz, head of the Florida Division of Emergency Management, accused 3M of selling N95 masks directly to foreign countries for cash, instead of the US. Moskowitz stated that 3M agreed to authorized distributors and brokers to represent they were selling the masks to Florida, but instead his team for the last several weeks "get to warehouses that are completely empty." He then said the 3M-authorized US distributors later told him the masks Florida contracted for never showed up because the company instead prioritized orders that came in later, for higher prices, from foreign countries (including Germany, Russia, and France). As a result, Moskowitz highlighted the issue on Twitter, saying he decided to "troll" 3M.[155][156][157] Forbes reported that "roughly 280 million masks from warehouses around the US had been purchased by foreign buyers [on March 30, 2020] and were earmarked to leave the country, according to the broker — and that was in one day", causing massive critical shortages of masks in the US.[158][159]

As more and more countries restricted the export of N95 masks, Novo Textiles in British Columbia announced plans to start producing N95 masks in Canada.[160] AMD Medicom in Quebec had long been the main Canadian company producing N95s, but China, France, the Republic of China (Taiwan) and the United States all banned exports of medical equipment, barring Medicom's factories there from exporting the masks to Canada. The Government of Canada subsequently awarded Medicom a 10-year contract to build a factory to produce masks in Montreal.[161]

The mask industry

Manufacturing

.jpg)

As of 2019, mainland China manufactured half the world output of masks.[162] As COVID-19 spread, enterprises in several countries quickly started or increased the production of face masks.[163] Cottage industries and volunteer groups also emerged, manufacturing cloth masks for localized use. They used various patterns, including some with a bend-to-fit nosepiece inserts. Individual hospitals developed and requested a library of specific patterns.[164][165][166][167]

In the first five months of 2020, 70802 new companies registered in China to make or trade face masks, a 1256% increase compared to 2019, and 7296 new companies registered to make or trade meltblown fabric, a key component of face masks, a 2277% rise from 2019.[168]

In April, however, the Chinese government stepped in with tighter regulations. 867 producers of the meltblown fabric were shut down in Yangzhong city alone. Many speculative manufacturers have been forced to quit due to changing export rules and tighter licensing requirements in China and weaker demand for lower quality products globally.[168]

Distribution

Some clinical stockpiles have proved inadequate in scale, and markets have expanded as non-medical consumers started obeying mandated mask-wearing or determined that masks might help or encourage them. Worldwide demand for face masks has resulted in masks shipping around the globe as a result of commercial transactions or of donations.[169]

Society and culture

Attitudes

In East Asian societies, a primary reason for mask-wearing is to protect others from oneself.[171][172] The broad assumption behind the act is that anyone, including seemingly healthy people, can be a carrier of the coronavirus.[172] The usage of masks is seen as a collective responsibility to reduce the transmission of the virus.[173] A face mask is thus seen as a symbol of solidarity in Eastern countries.[173] Elsewhere, the need for mask-wearing is still often seen in an individual's perspective where masks only serve to protect oneself.[171] However, a cultural shift towards the message of solidarity has gradually taken place as the pandemic continued.[174] Masking is shifting to become a new social norm.[175][176]

Existing cultural norms and social pressure may impede mask-wearing in public, which explains why masking has been avoided in the West.[177] According to Joseph Tsang, a Hong Kong doctor and infectious disease expert, the promotion of universal masking may resolve perceptions against mask-wearing, because mask-wearing is intimidating if few people wear masks due to cultural barriers, but if all people wear masks it shows a message that people are in this together.[110] In Barceló and Sheen (6 May 2020), empirical evidence shows that an individual's likelihood of voluntarily wearing a mask is positively correlated with the proportion of uptake in the surrounding area.[178]

In the Western world, the public usage of masks still often carries a large stigma,[171][173][179] as it is seen as a sign of sickness.[179] This stigmatization is a large obstacle to overcome, because people may feel too ashamed to wear a mask in public and therefore opt to not wear one.[180] However, there is also a divide within the Western world, as seen in the Czech Republic and Slovakia where mass mobilization has occurred to reinforce the solidarity in mask-wearing since March 2020.[171]

Masking has been subjected to racial politics in Western countries.[181] For instance, it has been heavily racialized as an Asian phenomenon.[173] This has been reinforced in a lot of media discourses, where imagery of Asian people in masks often accompany unrelated stories about the pandemic.[181][182] The focus on race has brought hostility towards Asians who are confronted with the choice to mask as precaution while they face discrimination for it.[181][183] Huang Yinxiang, a sociologist from the University of Manchester, described maskaphobia—negative prejudice, fear or hatred against people wearing face masks—as making Asians in Western countries into targets for racists who want to normalize and justify xenophobia during the COVID-19 outbreak.[184] Likewise, people from certain groups such as Black Americans may not feel comfortable wearing masks, especially those that are not clearly medical but homemade masks, due to concerns of racial profiling.[185][186][187]

Gender plays a role in the willingness to wear masks during the pandemic; men are overall less inclined to mask in public than women.[188][189] There are indications that men are more likely to feel negative emotions (such as shame) and stigma for wearing masks.[188][189] It is suggested that this male behavior is driven by a sense of masculinity, where the act of masking is possibly perceived to run counter to it, which leads to an increase in men not wearing masks during the pandemic.[190][191]

Mask-wearing has been called a prosocial behavior in which one protects others within their community.[192][193] On social media, there has been an effort with the #masks4all campaign to encourage people to use masks.[194] Nevertheless, there have many occurrences of violence and hostility by people who became aggressive after they were requested to wear a mask or saw people in masks in places related to the service industry.[195][196][197][198] This has led to concerns about worker safety, with employees discouraged to actively enforce masking policies due to the potential of hostile situations, while enforcement by official authorities is severely lacking.[199]

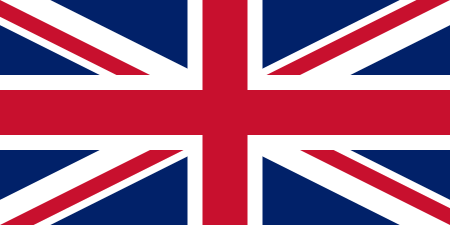

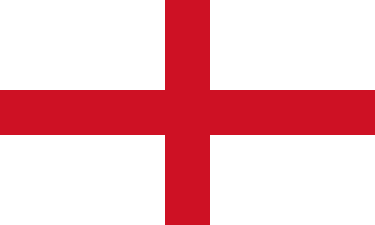

There have also been concerns that the wearing of masks may also further isolate disadvantaged communities. Concerns had been expressed that those who are deaf or hard-of-hearing would be unable to communicate while wearing a face mask. This led to wider distributions of transparent masks, which allow for lip reading.[200][201] Similar concerns over difficulty in communicating have been expressed by those who may depend on dogs for theraputic or social reasons.[202] Convervsely, people who are exempt from wearing masks on medical grounds or due to a disability, fear they will be subjected to abuse for not wearing a mask, even if they are legally exempt from doing so. In the United Kingdom, charity Disability Rights UK has reported a significant increase in reports of people being confronted on trains and buses.[203]

Trends

Among the European countries surveyed by YouGov, the likelihood for people to mask has been split: In Northern Europe (e.g., Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark), people are very unlikely to wear a mask.[204] In Western Europe (e.g., Italy, Spain, France, and Germany), people were initially unlikely to use a mask, but mask wearing greatly changed from low levels in March to higher levels in May.[204] An exception was the United Kingdom where mask usage only grew gradually during this time,[204] but it rose very quickly after official policy changes in July mandated masking in stores.[205]

Politics

.jpg)

.png)

Although authorities in especially Asia have been recommending people to wear face masks in public, in many other parts of the world, conflicting advice have caused a lot of confusion among the general population.[207] Several governments and institutions, such as in the United States, have initially dismissed the use of face masks by the general population, often with misleading or incomplete information about the usefulness of masks.[208][209][210] Commentators have attributed the anti-mask messaging to efforts to manage the mask shortages, as governments did not act quickly enough, remarking that the claims go beyond the science or were simply lies.[210][211][212][213] On 12 June 2020, Anthony Fauci, a key member of the White House coronavirus task force, confirmed that the American public were not told to wear masks from the beginning due to the shortages of masks and explained that masks do actually work.[214][215][216][217][218]

In the United States, public masking has become a political issue, as opponents argue that it inhibits personal freedom and proponents emphasize the importance of masks for public health.[219] Some people may see it as a political statement.[220] Party affiliation partly determined how likely people were to embrace the wearing of masks in public.[220][221] Democrats were more likely to wear masks than Republicans.[220][221] Masks have become an aspect of the culture war that has emerged over the course of the pandemic.[219][220][221] Commentators argue that the resistance against masks partly stems from the confusing and mixed messaging about masking.[219][222][223]

Tom Jefferson and Carl Heneghan from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine suggest that issues in the value placed on evidence and the lack of clear answers to guide decision-makers have resulted in polarizing and politicized views influencing global interventions.[224]

Despite widespread implementation of masking policies globally, in some countries, large rallies have taken place in protest against masking mandates.[225][226][227] In Canada, the anti-mask crowd has hailed their protests as the so-called "March to Unmask."[227][228] In the United Kingdom, new protests came in the wake of the official announcement that masking will be compulsory in shops.[225]

In April 2020, health officials from Taiwan's Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC) pushed back on school bullying of young boys in pink face masks. At a press conference breaking gender norm barriers, the health officials wore pink masks, as various government agencies demonstrated solidarity by changing the colors on their Facebook pages to pink. One of the officials participating in the press conference later tweeted, "Pink is for everyone and no color is exclusive for girls or boys. Gender equality lies at the heart of Taiwan values." The press conference was held amid reports that male students were too embarrassed to wear their pink face masks, jeopardizing their safety and the safety of others in the face of COVID-19.[229]

Religion

Christian clergy from the Lutheran, Catholic, Presbyterian, Anglican, Baptist and Mormon traditions, as well as those from the Jewish, Buddhist and Unitarian religions have implored people to wear masks.[230]

James Martin, a Jesuit Catholic priest, who affirmed a belief in a consistent life ethic, specifically stating that a "reverence for life includes a desire to care for the unborn child in the womb, the elderly person in danger of euthanasia, the refugee starving on the border, the L.G.B.T. youth tempted to suicide and the inmate being readied for execution on death row".[231] Martin stated that to that list, sacred lives also include "the woman standing in line at the grocery store checkout counter, the elderly man seated in a church pew or the office worker who has just stepped aboard public transportation."[231] Because masks prevent of contagion, the act of wearing a mask, in Martin's view, is being pro-life.[231]

Fashion

Face masks have had an impact on fashion, with the masks themselves becoming fashion statements, haute couture brands having pivoted to address both public health and aesthetic needs.[232][233][234][235] As public usage of fabric masks have become more commonplace, people have started to consider the aesthetical design of it.[236]

The Walt Disney Company introduced uniformed face masks for their employees at Disney World and Disneyland domestically.[237][238]

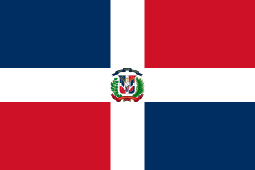

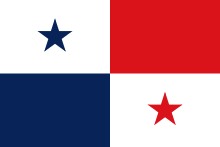

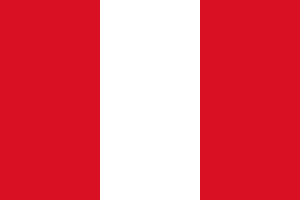

Mask use and policies by country and territory

| Country/territory | % |

|---|---|

| 92 | |

| 90 | |

| 88 | |

| 86 | |

| 86 | |

| 85 | |

| 85 | |

| 84 | |

| 83 | |

| 82 | |

| 81 | |

| 80 | |

| 80 | |

| 79 | |

| 79 | |

| 75 | |

| 74 | |

| 71 | |

| 69 | |

| 67 | |

| 65 | |

| 41 | |

| 7 | |

| 6 | |

| 5 | |

| 4 |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Northern Ireland: The wearing of face masks on public transport was compulsory from 10 July.[353] While the wearing of face masks in retail stores is currently voluntary, Deputy First Minister Michelle O'Neill has advised this may become mandatory, if sufficient number of people were not wearing them by 20 August.[354]

.svg.png)

References

- "Q&A: Masks and COVID-19". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Recommendation Regarding the Use of Cloth Face Coverings, Especially in Areas of Significant Community-Based Transmission". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Using face masks in the community – Reducing COVID-19 transmission from potentially asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic people through the use of face masks". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 8 April 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Tufekci, Z; Howard, J.; Greenhalgh, T. (22 April 2020). "The Real Reason to Wear a Mask. Much of the confusion around masks stems from the conflation of two very different uses". The Atlantic. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Masks4All. "What Countries Require Masks in Public or Recommend Masks?". Masks4All. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Setti, L.; Passarini, F.; De Gennaro, G. (23 April 2020). "Airborne Transmission Route of COVID-19: Why 2 Meters/6 Feet of Inter-Personal Distance Could Not Be Enough". Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17(8) 2932 (8): 2932. doi:10.3390/ijerph17082932. PMC 7215485. PMID 32340347.

- Parshina-Kottas, Y.; Saget, B.; Patanjali, B. (14 April 2020). "This 3-D Simulation Shows Why Social Distancing Is So Important". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Sheikh, K.; Gorman, J.; Chang, K. (14 April 2020). "Stay 6 Feet Apart, We're Told. But How Far Can Air Carry Coronavirus? Most of the big droplets travel a mere six feet. The role of tiny aerosols is the "trillion-dollar question."". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Reynolds, G. (15 April 2020). "For Runners, Is 15 Feet the New 6 Feet for Social Distancing? When we walk briskly or run, air moves differently around us, increasing the space required to maintain a proper social distance". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Ting, Victor (4 April 2020). "To mask or not to mask: WHO makes U-turn while US, Singapore abandon pandemic advice and tell citizens to start wearing masks". South China Morning Post.

- Lam, Simon Ching; Suen, Lorna Kwai Ping; Cheung, Teris Cheuk Chi (May 2020). "Global risk to the community and clinical setting: Flocking of fake masks and protective gears during the COVID-19 pandemic". American Journal of Infection Control. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.05.008. PMC 7219383. PMID 32405127.

- Wei, Neo Kang (6 May 2019). "What is PM0.3 and Why Is It Important?". Smart Air Filters.

- "Respiratory Protection Against Airborne Infectious Agents for Health Care Workers: Do surgical masks protect workers?" (OSH Answers Fact Sheets). Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety. 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Theresa Tam offers new advice: Wear a non-medical face mask when shopping or using public transit,The Globe and Mail, 6 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Godoy, Laura R. Garcia; Jones, Amy E.; Anderson, Taylor N.; Fisher, Cameron L.; Seeley, Kylie M. L.; Beeson, Erynn A.; Zane, Hannah K.; Peterson, Jaime W.; Sullivan, Peter D. (1 May 2020). "Facial protection for healthcare workers during pandemics: a scoping review". BMJ Global Health. 5 (5): e002553. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002553. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 7228486. PMID 32371574. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Davies, Anna; Thompson, Katy-Anne; Giri, Karthika; Kafatos, George; Walker, Jimmy; Bennett, Allan (22 May 2013). "Testing the Efficacy of Homemade Masks: Would They Protect in an Influenza Pandemic?". Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 7 (4): 413–418. doi:10.1017/dmp.2013.43. ISSN 1935-7893. PMC 7108646. PMID 24229526.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020.

- van der Sande, Marianne; Teunis, Peter; Sabel, Rob (9 July 2008). Pai, Madhukar (ed.). "Professional and Home-Made Face Masks Reduce Exposure to Respiratory Infections among the General Population". PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science (PLoS). 3 (7): e2618. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2618V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002618. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2440799. PMID 18612429.

- Davies, Anna; Thompson, Katy-Anne; Giri, Karthika; Kafatos, George; Walker, Jimmy; Bennett, Allan (2 May 2013). "Testing the Efficacy of Homemade Masks: Would They Protect in an Influenza Pandemic?". Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 7 (4): 413–418. doi:10.1017/dmp.2013.43. ISSN 1935-7893. PMC 7108646. PMID 24229526.

- Rengasamy, S.; Eimer, B.; Shaffer, R. E. (2 June 2010). "Simple Respiratory Protection—Evaluation of the Filtration Performance of Cloth Masks and Common Fabric Materials Against 20–1000 nm Size Particles". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford University Press (OUP). 54 (7): 789–98. doi:10.1093/annhyg/meq044. ISSN 1475-3162. PMID 20584862.

- Konda, Abhiteja; Prakash, Abhinav; Moss, Gregory A.; Schmoldt, Michael; Grant, Gregory D.; Guha, Supratik (2 April 2020). "Aerosol Filtration Efficiency of Common Fabrics Used in Respiratory Cloth Masks". ACS Nano. American Chemical Society (ACS). 14 (5): 6339–6347. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c03252. ISSN 1936-0851. PMID 32329337.

- "Washable Face Masks Thanks to Electrospun Nanofibers". Medgadget. 23 March 2020.

- Hwang, Wontae; Pang, Changhyun; Chae, Heeyeop (28 October 2016). "Fabrication of aligned nanofibers by electric-field-controlled electrospinning: insulating-block method". Nanotechnology. 27 (43): 435301. Bibcode:2016Nanot..27Q5301H. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/27/43/435301. PMID 27651316.

- Robertson, Paddy (21 April 2020). "The Ultimate Guide to Homemade Face Masks for Coronavirus". Smart Air Filters.

- "How to Safely Wear and Take Off a Cloth Face Covering" (PDF). CDC.

- "N95 Respirators and Surgical Masks (Face Masks)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- , "US 5496507 A – Method Of Charging Electret Filter Media The Lens – Free & Open Patent and Scholarly Search"

- "PROPERTIES OF DIFFERENT TYPES OF MASKS" (PDF). Government of New South Wales Clinical Excellence Commission. February 2020.

- Jung, James (17 March 2020). "KAIST Researchers Develop Highly Reusable Mask Filter". KoreaTechToday.

- "Recommended Guidance for Extended Use and Limited Reuse of N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators in Healthcare Settings". cdc.gov. NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic. CDC. 27 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020.

- Long, Y; Hu, T; Liu, L; Chen, R; Guo, Q; Yang, L; Cheng, Y; Huang, J; Du, L (13 March 2020). "Effectiveness of N95 respirators versus surgical masks against influenza: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Evidence-based Medicine. 13 (2): 93–101. doi:10.1111/jebm.12381. PMC 7228345. PMID 32167245.

- "Not Enough Face Masks Are Made In America To Deal With Coronavirus". NPR. 5 March 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Chinese mask makers use loopholes to speed up regulatory approval". Financial Times. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Robertson, Paddy (15 March 2020). "Comparison of Mask Standards, Ratings, and Filtration Effectiveness". Smart Air Filters.

- 中华人民共和国医药行业标准:YY 0469–2011 医用外科口罩(Surgical mask) (in Chinese)

- 中华人民共和国医药行业标准:YY/T 0969–2013 一次性使用医用口罩(Single-use medical face mask) (in Chinese)

- "NIOSH-Approved N95 Particulate Filtering Facepiece Respirators – A Suppliers List". U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Respirator Trusted-Source: Selection FAQs". U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 12 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Zie, John (19 March 2020). "World Depends on China for Face Masks But Can Country Deliver?". Voice of America.

- Feng, Emily (16 March 2020). "COVID-19 Has Caused A Shortage Of Face Masks. But They're Surprisingly Hard To Make". NPR.

- "Comparison of FFP2, KN95, and N95 and Other Filtering Facepiece Respirator Classes" (PDF). 3M Technical Data Bulletin. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Strategies for Optimizing the Supply of N95 Respirators: Crisis/Alternate Strategies". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Patel, Rajeev B.; Skaria, Shaji D.; Mansour, Mohamed M.; Smaldone, Gerald C. (28 April 2016). "Respiratory source control using a surgical mask: An invitro study". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 13 (7): 569–576. doi:10.1080/15459624.2015.1043050. ISSN 1545-9624. PMC 4873718. PMID 26225807.

- Mills, Stu (10 April 2020). "Researchers looking at innovative ways to sterilize single-use masks". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Bach, Michael. "Understanding respiratory protection options in Healthcare: The Overlooked Elastomeric". NIOSH Science Blog. CDC.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020.

- Boškoski, Ivo; Gallo, Camilla; Wallace, Michael B.; Costamagna, Guido (27 April 2020). "COVID-19 pandemic and personal protective equipment shortage: protective efficacy comparing masks and scientific methods for respirator reuse". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.04.048. ISSN 0016-5107. PMC 7184993.

- The Use and Effectiveness of Powered Air Purifying Respirators in Health Care: Workshop Summary. 2. Defining PAPRs and Current Standards. NCBI. National Academies Press (US). 7 May 2015.

- Radonovich, Lew (5 September 2017). "Elastomeric and Powered-Air Purifying Respirators in U.S. Healthcare" (PDF).

- Layt, Stuart (14 April 2020). "Queensland researchers hit sweet spot with new mask material". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Technology (QUT), Queensland University of. "New mask material can remove virus-size nanoparticles". QUT. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Leichman, Abigail Klein (28 January 2020). "New antiviral masks from Israel may help stop deadly coronavirus". Israel21c. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Israel to receive 120,000 coronavirus-repelling face masks". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Karlin, Susan (12 May 2020). "Scientists are racing to design a face mask that can rip coronavirus apart". Fast Company. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Vavra, Chris (18 April 2020). "Self-sanitizing face mask project for COVID-19 research receives NSF grant". Control Engineering. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Lindsley, WG; Noti, JD; Blachere, FM; Szalajda, JV; Beezhold, DH (2014). "Efficacy of face shields against cough aerosol droplets from a cough simulator". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 11 (8): 509–18. doi:10.1080/15459624.2013.877591. PMC 4734356. PMID 24467190.

- "Severe Respiratory Disease associated with a Novel Infectious Agent". Government of Hong Kong. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Updates on Wuhan Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Local Situation". MoH.gov.sg. Ministry of Health of Singapore. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care and in health care settings in the context of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak". World Health Organization. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- "2019-nCoV: What the Public Should Do". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 4 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Puede que Asia haya tenido razón sobre el coronavirus y las mascarillas, y el resto del mundo se está convenciendo de ello". 1 April 2020.

- "Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19". World Health Organization. 5 June 2020.

- "Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19". World Health Organization. 5 June 2020.

- "Q&A: Masks and COVID-19". World Health Organization. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. For more details on fabrics, see also "Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19". World Health Organization. 5 June 2020.

- "Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care and in health care settings in the context of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak: interim guidance, 29 January 2020". World Health Organization. 29 January 2020.

- "Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care, and in health care settings in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 19 March 2020". World Health Organization. 19 March 2020.

- "Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 6 April 2020". World Health Organization. 6 April 2020.

- Winn, Patrick (1 April 2020). "Will the US ever mimic Asia's culture of 'universal masking'?". Public Radio International.

- Tufekci, Zeynep (17 March 2020). "Why Telling People They Don't Need Masks Backfired". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Feuer, William; Higgins-Dunn, Noah (8 June 2020). "Asymptomatic spread of coronavirus is 'very rare,' WHO says". CNBC.

- Mantzari, Eleni; Rubin, G James; Marteau, Theresa M (26 July 2020). "Is risk compensation threatening public health in the covid-19 pandemic?". BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2913.

- Hunt, Katie (27 July 2020). "Face mask wearers don't get lax about washing hands, study suggests". CNN.

- "Q&A: Masks and COVID-19". World Health Organization. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020.

- "Use of cloth face coverings to help slow the spread of COVID-19". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 3 April 2020.

- Fisher, Kiva A.; Barile, John P.; Guerin, Rebecca J.; Vanden Esschert, Kayla L.; Jeffers, Alexiss; Tian, Lin H.; Garcia-Williams, Amanda; Gurbaxani, Brian; Thompson, William W.; Prue, Christine E. (17 July 2020). "Factors Associated with Cloth Face Covering Use Among Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, April and May 2020". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. pp. 933–937. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6928e3.

- "Considerations for wearing cloth face coverings : help slow the spread of COVID-19". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 16 July 2020.

- "Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020.

- "Strategies for Optimizing the Supply of N95 Respirators". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 June 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020.

- López, Canela. "Celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow and Kate Hudson were criticized for wearing face masks early in the pandemic. Here's what changed". Business Insider.

- "Transcript for CDC Telebriefing: CDC Update on Novel Coronavirus". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 February 2020.

- "Fact check: Medical discharge document includes outdated CDC guidance on face masks". Reuters. 3 July 2020.

- Jingnan, Huo (10 April 2020). "Why There Are So Many Different Guidelines For Face Masks For The Public". NPR.

- Mills, Russell (29 July 2020). "CDC director: Face masks "our most powerful tool" to fight COVID-19". 102.3 KRMG.

- Wetsman, Nicole (3 April 2020). "Masks may be good, but the messaging around them has been very bad". The Verge.

- Jankowicz, Mia (1 June 2020). "Fauci said US government held off promoting face masks because it knew shortages were so bad that even doctors couldn't get enough". Business Insider.

- Henry, Tanya Albert (17 July 2020). "CDC's Dr. Redfield: This is why everyone should be wearing masks". American Medical Association.

- Brooks, John T.; Butler, Jay C.; Redfield, Robert R. (14 July 2020). "Universal Masking to Prevent SARS-CoV-2 Transmission—The Time Is Now". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.13107.

- "For different groups of people: how to choose masks". NHC.gov.cn. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

Disposable medical masks: Recommended for: · People in crowded places · Indoor working environment with a relatively dense population · People going to medical institutions · Children in kindergarten and students at school gathering to study and do other activities

- 疫情通报 [Outbreak notification]. NHC.gov.cn (in Chinese). National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "关于印发公众科学戴口罩指引的通知引". NHC.gov.cn (in Chinese). Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020.

- "Prevention of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (PDF). Centre for Health Protection. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Leung, Hillary (12 March 2020). "Why Wearing a Face Mask Is Encouraged in Asia, but Shunned in the U.S." Time. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

Nearly everyone on Hong Kong's streets, trains and buses has been wearing a mask for weeks ...

- Kuhakan, Jiraporn (12 March 2020). "'Better than nothing': Thailand encourages cloth masks amid surgical mask shortage". Reuters.

- Cohen, Jon (27 March 2020). "Not wearing masks to protect against coronavirus is a 'big mistake,' top Chinese scientist says". Science.

- "Mandatory mask-wearing now the norm in Europe as COVID-19 cases rise". euronews. 24 July 2020.

- "Norway Makes First Face Mask Recommendation Since Pandemic Began". VOA News. 14 August 2020.

- "Denmark Recommends Face Masks On Public Transport". Barron's. 31 July 2020.

- "Denmark changes face mask guidelines: now advised on busy public transport". The Local dk. 31 July 2020.

- Kauranen, Anne (13 August 2020). "Finland recommends face masks as coronavirus cases creep up". Reuters.

- "Why are the Nordic countries still not recommending face masks?". The Local dk. 30 July 2020.

- Stoltenberg, Camilla (June 2020), "Should individuals in the community without respiratory symptoms wear facemasks to reduce the spread of COVID-19? – a rapid review" (PDF), Norwegian Institute of Public Health

- "No country for face masks: Nordics brush off mouth covers". medicalxpress. 30 July 2020.

- Tang, Julian W.; Nicolle, Andre D. G.; Pantelic, Jovan; Jiang, Mingxiu; Sekhr, Chandra; Cheong, David K. W.; Tham, Kwok Wai (22 June 2011). "Qualitative Real-Time Schlieren and Shadowgraph Imaging of Human Exhaled Airflows: An Aid to Aerosol Infection Control". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e21392. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621392T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021392. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3120871. PMID 21731730.

- "Why healthy Chinese wearing face masks outdoors?". NHC.gov.cn. National Health Commission. 23 March 2020. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Li, Isabelle; Zuoyan, Zhao (10 March 2020). "Q&A with HK microbiologist Yuen Kwok-yung who helped confirm coronavirus' human spread". The Straits Times.

- To, Kelvin Kai-Wang; Tsang, Owen Tak-Yin; Yip, Cyril Chik-Yan; Chan, Kwok-Hung; et al. (12 February 2020). "Consistent Detection of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Saliva". Clinical Infectious Diseases. Oxford University Press: ciaa149. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa149. PMC 7108139. PMID 32047895.

- Winn, Patrick (1 April 2020). "Will the US ever mimic Asia's culture of 'universal masking'?". Public Radio International.

- Cheng, Kar Keung; Lam, Tai Hing; Leung, Chi Chiu (16 April 2020). "Wearing face masks in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic: altruism and solidarity". The Lancet: S0140673620309181. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30918-1.

- Gandhi, Monica; Beyrer, Chris; Goosby, Eric (31 July 2020). "Masks Do More Than Protect Others During COVID-19: Reducing the Inoculum of SARS-CoV-2 to Protect the Wearer". Journal of General Internal Medicine. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06067-8.

- "How to avoid touching your face so much". BBC News. 18 March 2020.

- Greenhalgh, Trisha; Schmid, Manuel B; Czypionka, Thomas; Bassler, Dirk; Gruer, Laurence (9 April 2020). "Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis". BMJ. 369: m1435. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1435. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32273267. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Chu, Derek K; Akl, Elie A; Duda, Stephanie; Solo, Karla; Yaacoub, Sally; Schünemann, Holger J; et al. (27 June 2020). "Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9.

- Chan JF, Yuan S, Zhang AJ, Poon VK, Chan CC, Lee AC, Fan Z, Li C, Liang R, Cao J, Tang K, Luo C, Cheng VC, Cai JP, Chu H, Chan KW, To KK, Sridhar S, Yuen KY (30 May 2020). "Surgical mask partition reduces the risk of non-contact transmission in a golden Syrian hamster model for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (PDF). Clinical Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa644. ISSN 1058-4838.

- Cheng, Lilian (17 May 2020). "Masks work in lowering Covid-19 transmission rates: Hong Kong researchers". South China Morning Post.

- Ward, Alex (18 May 2020). "How masks helped Hong Kong control the coronavirus". Vox.

- Culbertson, Alix (19 May 2020). "Coronavirus: Wearing surgical masks can reduce COVID-19 spread by 75%, study claims". Sky News.

- "Reduction of secondary transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in households by face mask use, disinfection and social distancing: a cohort study in Beijing, China" (PDF). Archived from the original (pdf) on 7 June 2020.

- Mitze, Timo; Kosfeld, Reinhold; Rode, Johannes; Wälde, Klaus (29 June 2020). "Face Masks Considerably Reduce Covid-19 Cases in Germany". dx.doi.org. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Doung-ngern, Pawinee; Suphanchaimat, Rapeepong; Panjagampatthana, Apinya; Janekrongtham, Chaiwisar; Ruampoom, Duangrat; Daochaeng, Nawaporn; Eungkanit, Napatchakorn; Pisitpayat, Nichakul; Srisong, Nuengruethai (12 June 2020). "Associations between wearing masks, washing hands, and social distancing practices, and risk of COVID-19 infection in public: a cohort-based case-control study in Thailand". dx.doi.org. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Hendrix, M. Joshua (2020). "Absence of Apparent Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from Two Stylists After Exposure at a Hair Salon with a Universal Face Covering Policy — Springfield, Missouri, May 2020". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6928e2. ISSN 0149-2195.

- "CDC calls on Americans to wear masks to prevent COVID-19 spread". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 14 July 2020.

- 谢斌 张纯 (21 January 2020). "一罩难求:南都民调实测走访发现,线上线下口罩基本卖脱销". 南方都市报. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- 徐榆涵 (23 January 2020). "全球各地瘋搶口罩 專家:不必買N95". 聯合報. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- 刘灏 (21 January 2020). "广东市场监管部门:将坚决打击囤积居奇、哄抬价格等行为". 南方网. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "市场价格行为提醒书". n.d. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020.

- 陈泽云 (22 January 2020). "口罩买不到怎么办?这些药店平台春节期间持续供应". 金羊网. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- 新京报 (22 January 2020). "京东:禁止第三方商家口罩涨价". 新京报网. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- 新京报 (22 January 2020). "苏宁易购:口罩等健康类商品禁涨价,并开展百亿补贴". 新京报网. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- 新京报 (22 January 2020). "拼多多:对口罩等产品进行监测,恶意涨价者将下架". 新京报网. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Olga Khazan, Why We're Running Out of Masks, The Atlantic (10 April 2020).

- Nick Miroff. "Protective gear in national stockpile is nearly depleted, DHS officials say". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Juliet Eilperin, Jeff Stein, Desmond Butler & Tom Hamburger, U.S. sent millions of face masks to China early this year, ignoring pandemic warning signs, The Washington Post (18 April 2020).

- "Pénurie de masques : une responsabilité partagée par les gouvernements". Public Senat (in French). 23 March 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- BFMTV. "Pénurie de masques: pourquoi la France avait décidé de ne pas renouveler ses stocks il y a neuf ans" (in French). BFMTV. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Roy, Soline; Barotte, Nicolas (19 March 2020). "Quand l'État stratège a renoncé à renouveler ses stocks de masques". Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "France to produce 40 million face masks by end of April for domestic battle against Covid-19". Radio France Internationale. 31 March 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Covid-19: French lawmakers to investigate where one and a half billion masks sent". Radio France Internationale. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Pénurie de masques : les raisons d'un "scandale d'État"". Franceinter.fr. n.d. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Countries reject Chinese-made equipment". BBC News. BBC. 30 March 2020.

- Choi, David (2 April 2020). "Chinese government rejects allegations that its face masks were defective, tells countries to 'double check' instructions". Business Insider France.

- "Trudeau says Canada will not pay full price for 8 million sub-standard masks". CTVNews. 9 May 2020.

- Bronskill, Jim (8 May 2020). "Federal government rejects 8 million N95 masks from single distributor". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Johnson, Marty (26 March 2020). "Feds have 1.5 million expired N95 masks in storage despite CDC clearing them for use on COVID-19: report". The Hill. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Evan, Melanie; Hufford, Austen (7 March 2020). "Critical Component of Protective Masks in Short Supply – The epidemic has driven up demand for material in N95 filters; 'everyone thinks there is this magic factory somewhere'". The Wall Street Journal.

- Fabian, Jordan; Clough, Rick (2 April 2020). "Trump Attacks 3M Over Mask Production, Drawing Company Pushback". Bloomberg.

- Whalen, Jeanne; Helderman, Rosalind S.; Hamburger, Tom (3 April 2020). "Inside Americas Mask Crunch". The Washington Post.

- Betschka, Julius; Fröhlich, Alexander (3 April 2020). "Berlins Innensenator spricht von 'moderner Piraterie'". Der Tagesspiegel (in German).

- "Schutzmasken konfisziert? Schwere Vorwürfe aus Berlin: Jetzt reagiert das Weiße Haus". t-online.de. 4 April 2020.

- Fröhlich, Alexander (4 April 2020). "200,000 respirators not confiscated: Delivery for Berlin police was bought in Thailand at a better price". Der Tagesspiegel.

- "Berlin lets mask slip on feelings for Trump's America". Politico Europe. 10 April 2020.

- Tisdall, Simon (12 April 2020). "US's global reputation hits rock-bottom over Trump's coronavirus response". The Guardian.

- Halon, Yael (3 April 2020). "Florida emergency management official says 3M selling masks to foreign countries: 'We're chasing ghosts'". Fox News Channel. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Interview With Jared Moskowitz, Director of Florida's Division of Emergency Management". WFOR-TV. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Man, Anthony (5 April 2020). "Florida emergency management chief says state will have enough ICU beds and ventilators". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- DiSalvo, David (30 March 2020). "I Spent A Day In The Coronavirus-Driven Feeding Frenzy Of N95 Mask Sellers And Buyers And This Is What I Learned". Forbes. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Natasha Bertrand; Gabby Orr; Daneil Lippman; Nahal Toosi (31 March 2020). "Pence task force freezes coronavirus aid amid backlash". Politico. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "COVID-19: Coquitlam company retools, will be first in Canada to produce N95 respirators". 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Toronto Star. Saturday 23 May, front page. As imports hit roadblock, when can Canada make its own N95 masks?

-

Bradsher, Keith; Alderman, Liz (2 April 2020). "The World Needs Masks. China Makes Them, but Has Been Hoarding Them". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

China made half the world’s masks before the coronavirus emerged there, and it has expanded production nearly 12-fold since then.

-

For example:

"Face mask production shows no sign of stopping". PAhomepage. Nexstar Broadcasting, Inc. 22 April 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

[...] Martz Technologies in Berwick [in Pennsylvania] [...] turned their warehouse into a face mask factory.

- Enrich, David; Abrams, Rachel; Kurutz, Steven (25 March 2020). "A Sewing Army, Making Masks for America". The New York Times.

-

Levy, Jason (4 May 2020). "Need for masks spawns cottage industry". Republican-American. Waterbury CT: Republican American. Retrieved 7 May 2020.