European Union

The European Union (EU) is an economic and political union of 28 member states that are located primarily in Europe. Additional countries participate in specific areas, such as immigration controls and currency.

Travel between member states is generally much easier than crossing other international borders, both for residents and for people from outside the union.

Understand

History

The European Union was in part motivated by the catastrophe of World War II, with the idea that European integration would prevent such a disastrous war from happening again. The idea was first proposed by the French foreign minister Robert Schuman in a speech in 1950. Schuman was from Alsace – a region at the heart of three violent changes of hand between Germany and France between 1870 and 1944. The speech resulted in the first agreements in 1951: the European Coal and Steel Community, which formed the basis for the European Union. Another important milestone was the Treaty of Rome which came into force on 1 January 1958, establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) which evolved into today's European Union.

While the attempt to create a "European Army" failed in the 1950s due to the instability of the Fourth French Republic which was preoccupied with Indochina and Algeria at the time, the six founding members (Italy, France, Germany and the Benelux countries) pressed on with deeper integration and the reduction of barriers to trade and free movement. While the United Kingdom at first saw itself as a benevolent spectator more focused on its special relationship with the U.S. and with its empire and Commonwealth, by the 1960s the French veto was the only thing keeping them from joining. The UK joined the EEC in 1973 together with Ireland and Denmark. During the 1970s military dictatorships fell in Greece, Spain and Portugal, and democracy was reinstated. A few years later, these countries joined the EEC.

The EFTA (European Free Trade Area) was set up as an alternative of sorts to the EEC/EU, with EFTA members mostly participating in the trade aspects of the EU but foregoing other forms of deeper integration. Most former EFTA countries have now joined the EU. The EEA (European Economic Area), covering more areas of coordination, has now mostly taken the role of EFTA. Switzerland was part of both but has now replaced EEA membership with more or less equivalent bilateral agreements.

The mid-1980s to the mid-1990s were important years in the history of the EU, with the Single European Act (establishing a single market), the Schengen Agreement (establishing free movement), and the Maastricht Treaty (establishing the single currency and cooperation in several areas from agricultural policies to peacekeeping) being signed and coming into force. From that point on, the union became known as the EC (European Community) and eventually as the EU. Also during this time the Iron Curtain fell and Germany was reunited, which marked the beginning of the eastwards expansion of the union. The former EFTA members Austria, Finland and Sweden joined in 1995 (the Norwegians voted against membership), and the number of members almost doubled in the first decade of the 21st century, when a large number of the former Eastern Bloc countries joined.

The European Union has been active in brokering peace both at home (e.g. Northern Ireland) and abroad with mixed results. Successes include the relatively peaceful resolution after the Balkan and Kosovo wars, which resulted in two former Yugoslav Republics (Croatia and Slovenia) becoming EU members.

EU institutions have long been criticised for a perceived lack of democracy. Although democracy is a key European ideal, many think that the bureaucracy and the long chain between institutions and voters make the EU significantly less democratic than its member states. That the union was built around economics still shows: social and environmental issues (among others) are often handled as an afterthought. One answer to this criticism is that the European Parliament has been directly elected every five years since 1979, and has increased its power in the last decades. However, it still lacks some of the powers other parliaments have or has to share them with other bodies. Transparency has become much better, though still a problem. There is also an ongoing argument about how to bring the EU "closer" to its citizens. This has resulted in the EU being a highly-visible sponsor for many minor projects, including projects that traditionally were adequately handled locally at least in some countries. This sponsorship has been important in cases where the area has been neglected at the national level, and local resources have been scarce.

The fact that the European Union over the years has extended its area of policy hasn't been welcomed by everyone. This has lead to the emergence of far-right eurosceptic parties, maybe most notably the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), the French Front National (FN), the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV), and Germany's Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) which advocate their respective nations leaving the European Union.

Indeed, the European Union may soon experience its first departure, as the United Kingdom voted in a referendum in June 2016 to withdraw from the union, in a process known as Brexit. Hardliners in the ruling Conservative party and pressure from growing nationalist parties led to the referendum and the surprising victory for "leave". What the relation between UK and EU will be afterwards or, indeed, whether UK will leave, is still unclear, as there are ongoing difficulties in negotiations between the UK and EU, resulting in numerous extensions.

European institutions and organisation

There are at least four EU related groups of countries in Europe relevant to the traveller. They overlap but are not identical:

- The European Union (EU), a partial political and customs union.

- The European Economic Area (EEA) and EFTA, where most of the EU legislation applies. EEA comprises the EU plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. Switzerland used to be a member of the EEA and has equivalent bilateral agreements.

- The Eurozone comprises countries using and controlling the common currency, the euro (€), all of which are EU members. The euro is also the currency of Monaco, San Marino, the Vatican City and Andorra by agreement with the European Union. Kosovo and Montenegro also use the currency, though they are not part of the Eurozone and there is no agreement with the EU. Eventual adoption of the euro is a requirement for new members, however some existing EU countries neither use nor plan to introduce the euro.

- The Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) includes the EU, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and Vatican City. Transfers denominated in euros can be done with the same rules as with domestic systems. If you have an euro-denominated account, you can pay with chipped debit and credit cards (Mastercard or Visa) issued anywhere in the SEPA. A limitation is that not all countries in the SEPA have adopted the euro, so you still have to exchange from the euro to the national currency.

- The Schengen Area comprises countries using common visas and immigration controls. While primarily composed of EU member states, the Schengen area also includes Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Some EU members, such as the UK and the Republic of Ireland (which form their own Common Travel Area with the other British island nations), are not part of the Schengen agreement. Some small states in Europe — Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City — that in practice are inaccessible other than through the Schengen area are de facto part of the area given that there are no border controls. On the other hand, travel to and from Andorra and Gibraltar is controlled.

In addition to these there are European institutions independent of the EU. One such is the Council of Europe, an international organisation aiming to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe, and to promote European culture. All EU members are also members of the CoE, and the EU has adopted the Council's flag and anthem. Another is the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, created during the cold war to further understanding between governments across the Iron Curtain. It is still an important institution for the furthering of peace.

| Country | Eurozone? | Free Movement? | European Time zone1 |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| EET | |||

| CET | |||

| Euro | CET | ||

| Schengen | CET | ||

| Schengen | CET | ||

| Euro | Schengen | EET | |

| Euro | Schengen | EET | |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Euro | Schengen | EET | |

| Schengen | CET | ||

| Euro | WET | ||

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Euro | Schengen | EET | |

| Euro | Schengen | EET | |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Schengen | CET | ||

| Euro | Schengen | WET | |

| EET | |||

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Euro | Schengen | CET | |

| Schengen | CET | ||

| WET |

1 Winter time. In summer (last Sunday in March to Saturday before last Sunday in October): WET → WEST (UTC+0 → +1), CET → CEST (+1 → +2), EET → EEST (+2 → +3). Summer time may be abolished, probably with related changes in timezones.

2 The United Kingdom voted by referendum in June 2016 to leave the EU. The departure is expected to happen in 2019, though the details on departure procedures are being negotiated and have yet to be determined.

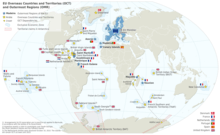

There are also territories around the world outside of continental Europe that belong to the European Union owing to the sovereignty of an EU member and subsequent agreement:

|

Territories outside of continental Europe and not included in the list above are not considered part of the European Union, even if they belong to EU nations. Territories such as New Caledonia (France) and Greenland (Denmark), and all overseas territories of the United Kingdom with the exception of Gibraltar have separate entry and travel requirements. However, even in territories that aren't part of the European Union, certain EU regulations relevant to travel may apply. On the other hand, even in certain places that are part of the EU certain exceptions to EU or national laws relevant to travel apply.

Get in

.jpg)

- See also: Travelling around the Schengen Area

The EU does not have an all encompassing immigration policy, and therefore immigration controls are in principle specific to each country. Many of its members have however adopted the Schengen Agreement, which makes travel very easy between these. Also some non-EU countries (Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Iceland) belong to the Schengen area, while three European micro-states – Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City – do not have any immigration controls with the Schengen countries.

There is an earlier, related but separate, concept of free movement inside EU, which makes moving and working across borders easy for EU/EEA nationals regardless of Schengen.

There are usually no border controls between countries that have signed the Schengen Agreement. Members of Schengen are still permitted to introduce border checks temporarily for security reasons, such as in connection with major events, and there may be random checks of travel documents, not only at the border. A visa granted for any Schengen Agreement signatory country is valid in all other countries that signed the treaty. People who need a visa should get a visa from their "primary destination" country. See Travelling around the Schengen Area for details

Travel between a Schengen Agreement country and any non-Schengen country will mostly result in the normal border checks. The United Kingdom and Ireland opted out and run a separate border control scheme and require passport controls of travellers arriving from other EU countries, while Romania, Bulgaria and Cyprus have not adopted Schengen yet, despite joining the EU.

EU/EEA citizens

EU and EEA citizens, and the Swiss, have no restriction in travelling anywhere in the EU, although exceptions are occasionally applied for serious criminal convictions. They should use the immigration queue often signed "EEA". Passports may still be required when venturing out of the Schengen free travel area, and otherwise most EU states still require people to carry a form of official identification.

The citizens do not need visas to study or work in other EU countries (except possible restrictions on working for nationals of new EU members), but moving to another EU country for an extended time (more than three, six or twelve months) can cause a change of residency and mean they lose social welfare and healthcare benefits in their former country. Such longer stays may also require some special status, such as employed, student or pensioner with own funds. Many countries require registration of new long term residents, and a change of driving licence after one year.

Customs

Animals

.jpg)

Free movement inside the EU does not always apply to your pets. Relevant national rules should be consulted before travel.

EU citizens can travel within the EU with their cat, dog or ferret provided they have a European pet passport with required treatments documented. The most important compulsory treatments are those against rabies, and against the tapeworm Echinococcus in at least UK, Ireland, Malta and Finland.

Alcohol and tobacco from outside of the EU

You're legally allowed tax-free import from outside the EU of 1 litre of spirits (above 22% alcohol) or 2 litres of alcohol (e.g. sparkling wine below 22% alcohol) and 4 litres of non-sparkling wine and 16 litres of beer. If you're younger than 17, it is half these amounts or nothing at all. Amounts exceeding this must be reported at customs for paying (quite heavy) duties and taxes.

Amounts of tobacco allowed depend on your country of arrival.

Age restrictions on handling tobacco and alcohol vary by country.

Moving between countries inside the EU

There are no restrictions on moving goods between EU states. For certain types of goods, such as alcohol and tobacco, taxes of the country you are entering may have to be paid, unless the goods are for "personal use" (including as gifts and the like). Claiming that is not enough; if the authorities suspect the goods are for resale and you cannot convince them, you are in trouble. At a minimum they will ask you to pay the appropriate duty or face confiscation of the goods.

Some areas within the EU are not part of the customs union, e.g. alcohol bought on ferries going via the Åland islands has to be imported into the EU customs union.

Long stay with vehicles

If you plan on coming by car or yacht and staying for an extended period, check the rules not to have to register it locally – or how to register it without too many bad surprises. Generally the vehicle has to leave the EU within 18 months (get and keep papers proving entry date). Lending such a vehicle to an EU resident or to a non-relative is usually not allowed.

Currency

When travelling between EU countries with €10,000 or more in physical assets (euros, other currencies, precious metal etc.), you should check with authorities in each country whether special measures are needed. Maintaining your cash in an EU bank account effectively frees you from any such controls, since the free movement of capital is maintained across the EU.

You must declare at customs when leaving the EU with €10,000 or more in euros or the equivalent in other currencies.

Get around

Although the European Union is moving towards the standardization of travel around the EU, national laws do still vary and it is important to refer to the article for each country for planning your trip. Similarly, while open access and harmonization of railway legislation are intended to lead to an integrated railway market for all of Europe, national railways still dominate their countries and overlap tends to be limited.

By car

- See also: Driving in Europe

Most of the EU drives on the right. A few exceptions (Cyprus, Ireland, Malta and UK) drive on the left. There are no restrictions on these cars being driven to a country that drives on the other side. Extra care must be taken however; simple modifications to mirrors and headlights make driving somewhat easier.

All cars with the standard EU license plate may be driven without additional requirements in another EU country. Cars with other types of license plates must have an oval decal affixed to the car with the international licence plate country code.

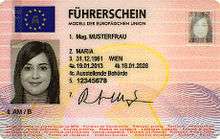

Driving licence

EU drivers are issued with a standard European Union driving licence. If you hold an EU driving licence then it may be used for driving throughout the EU. One important caveat is that age restrictions are not uniform across the EU, and your licence is not valid in any EU country unless you also meet the minimum age requirement.

If you hold a non-EU driving licence then this does not apply. You must still check with each country in order to determine whether it is valid.

By train

- See also: Rail travel in Europe

Border controls on international trains are usually done on the moving train and usually via spot checks. No international train stops at the border for significant amounts of time. Tickets can usually be bought from both national railways involved unless it is a "private" operator like Thalys. Prices may differ depending on the country where you buy the tickets. When you buy online, prices may vary depending on the website you use and sometimes even depending on the language version of the website. For trains to and from the UK, both exit and entry immigration checks are carried out at the departure station prior to boarding. The European Union also continues to push for more and better high speed rail connections across borders, designating prioritized corridors and spending EU resources as well as encouraging member states to spend their own or local funds on rail projects. Those corridors are summarized under the heading TEN-T - Trans European Network for Transportation.

Customer protection for travel issues

The EU is creating a common framework for travel between all the member states. Implications for issues you may face when travelling are covered under the Cope section.

Buy

The euro

|

Countries that have the euro as their official currency:

|

|

Exchange rates for Euros As of 25 January 2019:

Exchange rates fluctuate. Current rates for these and other currencies are available from XE.com |

The euro (€; EUR) is the common currency of 19 of the 28 countries that are members of the European Union. These are commonly called the Eurozone. The other 9 countries of the EU retain their national currencies.

One euro equals 100 cents, sometimes referred to as "eurocents".

When an EU country decides to adopt the euro, there is a transition period during which the local currency being phased out and euros are both legal tender. Be aware when this period ends, so as not to be left with the phased-out currency when it is no longer possible to use it for payment. The period may be as short as two weeks. If you end up with any of the obsolete currencies, you may be able to change it in a bank, but don't count on it. As of late 2018, no country in the EU is undergoing currency transition.

Even in EU countries that have not adopted the euro, it is usually the easiest foreign currency to exchange and is accepted in some places at the discretion of the business, but the exchange rate is unlikely to be favourable. For details, see the destination articles.

.png)

Euro banknotes are the same in all countries, except for small identifying national features, such as the first letter in the serial number and a printing code. Coins, on the other hand, will be identical on one side across countries, while the other side is country-specific. Although they look different, they can be used in any country within the Eurozone, for example a €1 coin with a Greek symbol can be used freely in Spain. There are also commemorative coins, with the national side looking different than on other coins from the same country, also legal tender everywhere.

- Normal coins: All eurozone countries have coins issued with a distinctive national design on one side, and a standard common design on the other side. Coins can be used in any eurozone country, regardless of the design used (e.g. a one-euro coin from Finland can be used in Portugal).

- Commemorative two euro coins: These differ from normal two euro coins only in their "national" side and circulate freely as legal tender. Each country may produce a certain amount of them as part of their normal coin production and sometimes "Europe-wide" two euro coins are produced to commemorate special events (e.g. the anniversary of important treaties).

- Other commemorative coins: Commemorative coins of other amounts (e.g. €10 or more) are much rarer, and have entirely special designs and often contain non-negligible amounts of gold, silver or platinum. While they are legal tender at face value, merchants may not accept them. As their material or collector value is usually much higher than their face value, you will most likely not find them in circulation.

Low-value coins are being phased out to varying degrees in several countries. For example, retailers in the Netherlands by law do not have to accept 1 and 2-cent coins, and all payments in cash will be rounded to the nearest 5 cents. In Finland payments in cash will likewise be rounded, but you can use the small coins for paying the rounded prices. In other countries, e.g. in Germany, those coins are treated as any other money and prices are not rounded – potentially leaving you with a handful of worthless coinage if you visit the Netherlands afterwards!

Value added tax

All purchases made within the European Union are subject to value added tax (VAT), included in the advertised prices. Non-residents can claim this amount back for goods they are taking back to their home country, under certain circumstances.

In many countries, the purchases must be above a minimum value at a single merchant. Therefore, you may benefit from making several purchases in one transaction, instead of visiting multiple stores. Not all merchants participate in the refund program, so check before finalizing the purchase. Present your passport at the register, and the seller will complete the necessary paperwork. Keep these documents, as you will need to present them to customs before leaving the EU. Paying with a non-EU credit card will make this easier.

EU regulations around VAT and duty do not apply to certain places inside the EU including the Canary Islands, the Channel Islands and Gibraltar.

Debit cards

Most EU countries use debit cards as the primary method of payment. However, some merchants in some countries only accept local-only debit card (i.e. those without a Visa or MasterCard logo).

If you have a euro currency debit card then you will not pay any additional charges from your bank when using the card in another EU country to:

- Withdraw cash from an ATM (although cash machine operators may charge their own fees)

- Pay for goods or services

Many large banks outside of the EU offer Traveler Cards in the euro currency that have the same benefits. Other debit and credit cards will also work but their use can be subject to fees.

European EC and Maestro are becoming less accepted in shops and machines while V-Pay, although not universal, is becoming more widespread.

Transferring money within the EU

There are nominally no restrictions in transferring funds between banks in different EU member states (although recently capital controls have been imposed on Greece and Cyprus). Within the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) transfers in euro are considered domestic and no additional charges can be applied in the normal case. This also applies to euro funds transferred to EU countries not belonging to the Eurozone (i.e. a transfer of €1,000 from Germany to Sweden will still be treated as a domestic transfer, even though the euro is not Sweden's currency).

For travellers this means that you can easily pay for goods and services throughout the Eurozone provided that you have a euro currency bank account anywhere in the EU.

See the article on Money for more information on the topic.

Work

An EU citizen can generally apply for jobs in any EU country under the same conditions as a local citizen. Work permits are not required, but certificates required for some types of work are not always recognised. Only Croatian citizens still face restrictions in some EU member countries.

Accessing social security benefits may depend on the length of time that you have worked in that country. EU/EEA citizens usually get the local social security – and lose the domestic – at the moment they start working, but there are exceptions.

The future status of EU workers in the United Kingdom is unclear as of January 2019. EU workers will enjoy full working and residency rights within the UK until the country leaves the European Union, which will be some time 2019 at the earliest. What happens after that is still very much uncertain, although a deal that allows EU citizens to remain in UK and UK citizens to remain in the EU is regarded as strongly desirable by both sides.

Stay healthy

Health coverage for EU residents

All EU countries operate public healthcare services that provide medical treatment for free or low cost to all residents. Non-EU residents can also use these systems, although they may have to pay a fee.

Travellers who live outside the EU and hold citizenship of an EU country may find that it is not possible to access the public health service in the same way as residents. British nationals (for example) must be resident in the United Kingdom for 6 months before they are entitled to take advanced treatment under the British national health service.

EU, EEA and Swiss residents can obtain a European Health Insurance Card that gives access to public medical care on the same terms as for local residents in any other country. This includes necessary treatment of chronic conditions, but not advanced medical treatment. The specific rules and practices vary quite a lot from country to country, but generally you will get cheap or free medical care. Not all doctors and hospitals operate within the reimbursement system, so check beforehand.

It is important to carry your Health Insurance Card at all times, since it will simplify greatly getting access to medical treatment abroad in any EU country. You still have the same rights to treatment without it, however you may be asked to pay all costs upfront, and then go through a complex process of reimbursement when you return home.

There are some restrictions:

- The Health Insurance Card cannot be used in Denmark by holders who are not citizens of an EU country (residency is not sufficient).

- Croatian citizens cannot use the Health Insurance Card in Switzerland

- The Health Insurance Card does not cover rescue and repatriation services

- Health Insurance Card does not cover private healthcare or planned treatment in another EU country

Health coverage for non-EU residents

All EU countries have public health services that are available for everyone to use. Non-EU residents may be charged for using these services, and the cost will vary between countries where the health service was used. Being an EU citizen who is resident outside the EU may mean that you fall into this category.

Emergency services are generally available to everyone without having to pay upfront. Nevertheless, private travel insurance should be considered before travel to the EU.

Medical prescriptions

Anyone visiting a doctor in the EU can request a cross-border prescription. This means that the prescription is valid and will be honoured in any other EU country.

Pharmacies may refuse to supply you with medicine without this prescription.

Cope

Air passenger rights

You are covered by the same set of passenger rights when flying:

- within the EU on any airline

- departing the EU on any airline

- arriving into the EU on an EU airline

These rights include:

- Ticket price: Your nationality and the location of purchase must not affect the price

- Online booking: All websites are legally obliged to clearly display all costs before booking, including taxes, airport charges, surcharges and other fees

- Financial compensation: You will be compensated a set amount when a flight is cancelled, delayed more than three hours (at arrival) or you are denied boarding.

- Within the EU: €250 for 1,500 km or less, €400 for over 1,500 km

- Between an EU and a non-EU airport: €250 for 1,500 km or less, €400 for 1,500-3,500 km, €600 for over 3,500 km

Travellers by air can submit an air passenger rights EU complaint form on return if they wish to apply for a refund or compensation.

Rail passenger rights

You are covered by the same set of passenger rights when travelling by rail between any two EU countries. These rules do not apply when travelling by rail inside an EU country, or travelling to or from a non-EU country, however some railways have adopted similar rules for domestic travel and in some countries of the EU they are national law.

If before your journey you are told that you will experience at least a one hour delay, then you are entitled to:

- Cancel your journey with an immediate refund

- Accommodation (if an overnight delay is expected)

- Meals and refreshments

- Refund if you continue your journey:

- 25% of the fare, if delayed between 1 and 2 hours

- 50% of the fare, if delayed more than 2 hours late.

- Compensation for lost or damaged registered luggage:

- Up to €1,300 per piece of luggage, if value can be proven

- €300 per piece of luggage, if value can not be proven

While it is possible to get a reimbursement for some of the above after you already paid them out of pocket, it is easier to directly contact the company while still on the train. The easiest way to do this is to talk to conductors or the like on the train when a delay is probable or when you are likely to miss your connection. They will usually give you forms for your refund and give you contact details for meals or hotels as most major railways have contracts with certain hotels in major cities to be able to hand out vouchers for stranded passengers.

Bus passenger rights

You are covered by the same set of passenger rights when travelling by bus between any two EU countries for a distance greater than 250 km. These rules do not apply when travelling by bus inside an EU country, or travelling to or from a non-EU country.

If you experience a two-hour delay in your journey, then you are entitled to either:

- Cancel your journey with a refund as well as be provided with a free journey back to your initial departure point

- Request alternative travel arrangements to your destination

Additionally you may be entitled to:

- Refreshments

- Accommodation overnight to a maximum €80 if required (except when delay is caused by severe weather)

Ship passenger rights

You are covered by the same set of passenger rights when travelling by ship from or to the EU. These rights generally do not extend to freight ships or small vessels (less than 13 passenger capacity).

- Cancel your journey with a refund as well as be provided with a free journey back to your initial departure point

- Request alternative travel arrangements to your destination

If you experience a delay arriving to your destination for more than 1 hour and it is not caused by bad weather, then you may be entitled to compensation worth between 25% and 50% of your paid ticket price.

Brexit

The United Kingdom is in negotiations to leave the European Union. There will be a lot of implications to travel, which are frustratingly unclear amid the prolonged political gridlock. Until the departure, the United Kingdom remains a full member of the EU, and the rights of other EU citizens will not be impacted. The date of departure has been repeatedly postponed and is now scheduled for 31 October 2019, though it could happen sooner.

As of April 2019, there is no clarity about what will happen after the UK leaves. A withdrawal treaty was agreed in November 2018, but it has been broadly rejected by most remainers and leavers in the UK as being not in the national interest – and in consequence rejected thrice by the parliament. The complex domestic political situation means that possibilities could still include crashing out without a deal, holding another referendum or even revoking Brexit completely and staying in the EU (the European Court of Justice has ruled that the United Kingdom can unilaterally abandon Brexit altogether).

The fundamental problem hindering an agreement, besides domestic politics, is that there are important reasons to keep the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland open, as well as the border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK (the Troubles and the Good Friday Agreement). The EU does not want to have open borders with a country with independent trade policies, while a Brexit which gives the UK no say on foreign trade is not what the proponents aim for.

On December 19, 2018, the EU published guidelines for a worst case scenario, known as Hard Brexit, stating that flights would be permitted to continue between the UK and the EU until at least March 2020. Free movement for EU and UK citizens would end however, and visa requirements will vary between the UK and each individual country in the EU. The EU has requested that each country provide 'generous' visa conditions to UK citizens, but that will be for each country to decide. UK issued pet passports will also not be valid any more.

If you are travelling to the UK and have insurance, mobile phone plans, etc., that are valid in the EU/EEA, keep an eye out for updates on when the UK will finally leave the EU, and check whether you need to amend them. Likewise the other way round.

Stay safe

Dialling 112 from any phone will connect you to all emergency services wherever you are in the EU. In some countries your call will be forwarded to a more specific number depending on the emergency, in others all or most emergencies are centrally handled. The 112 always has also English speaking staff.

Connect

If your mobile phone operator is based in the European Union, then from 15 June 2017 the default is for roaming to be no more expensive than domestic use. If a provider offers roaming services at all, they are bound to offer it to this price, although they may also offer other pricing schemes. There are other exceptions as well, so check the fine print. Especially plans with unlimited data for a fixed monthly fee may have surcharges for "unreasonable" roaming data use.

The Eurotariff, which dictates the maximum surcharge for roaming and the maximum cost with it included, applies wherever you travel in the EU, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein (from May 2016 and July 2014, should apply also to the exceptions to the 2017 rules; VAT not included):

| Type | Maximum surcharge | Maximum cost |

|---|---|---|

| Outgoing voice calls (every minute) | €0.05 | €0.19 |

| Incoming voice calls (every minute) | €0.0108 | €0.05 |

| Outgoing texts (every SMS message) | €0.02 | €0.06 |

| Online (data download, every megabyte) | €0.05 | €0.20 |

Be careful which network you connect to. By the EU border or in international waters (an intra-ship GSM network can have connections via satellite) your phone can choose a non-EU network, for which the maxima do not apply – the prices can then be outrageous. Where this is likely, be sure to choose network manually or to check the used network before each call.

While roaming in the EU, you will get an SMS stating the current tariffs whenever you change networks.

Visit

The EU isn't a travel destination in itself, although being regarded as an important project it does open many of its institutions in order to help people learn about it and its objectives. These are generally spread across the whole EU, although key institutions are to be found in a small area in Northern Europe in the cities of Brussels, Luxembourg, Strasbourg and Frankfurt.

The public transport between all the institutions below is excellent, and you can visit them all with a combination of train and tram. The memorials may be more remote, but can still be accessed by regular buses.

- 🌍 Parlamentarium, Willy Brandt building, Rue Wiertz / Wiertzstraat 60, B-1047, Brussels, Belgium. A dedicated visitor centre for the European Parliament in Brussels.

- 🌍 House of European History, Rue Wiertz 60, 1047 Brussels, Belgium. A display of European history from the perspective of the EU.

- 🌍 The Luxembourg campus, European Parliament, Robert Schuman Building Place de l'Europe, L-1499, Luxembourg, e-mail: epluxembourg@europarl.europa.eu. A lesser known part of the EU Parliament, Luxembourg actually quietly runs a lot of the EU administration. Group tours in advance are available, but should be made at least 2 months in advance. Visitors must be aged 14 and above. Apply via the email address. free.

- 🌍 Court of Justice of the European Union, Rue du Fort Niedergrünewald, L-2925, Luxembourg. Although each country still has its own legal framework, they are all bound by treaty to adopt EU law over time. The courts are central to the orderly running of the EU and visits are possible.

- 🌍 Alsace-Moselle Memorial, Lieu dit du Chauffour, F - 67 130, Schirmeck, France. Strasbourg and its Alsace region are highly symbolic of European identity, given that it changed hands between Germany and France no less than four times between 1870 and 1945. This EU monument tells the story of the people who lived through these times, and how this relates to modern Europe.

- 🌍 The European Parliament Hemicycle, Entrance Louise Weiss No 2 1, Allée du Printemps, F-67070, Strasbourg, France. Although Brussels is widely known as the 'capital' city of the EU, this building in the French city of Strasbourg is the official home of the Parliament. Politicians have to regularly move between Strasbourg and Brussels, largely because of historical French demands that a minimum number of sessions be held there. Nevertheless it is great place to visit, with the local Alsace region regarded as a mix of French and German culture. Visits to this building can be booked both inside and outside of official 'plenary' sessions, but check the website for the best times.

- 🌍 European Central Bank, Sonnemannstraße 20 (Main Building), 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. The financial arm of the EU, with direct monetary control of all current members of the Eurozone. Provides visits for education and architecture. It is building a dedicated visitor centre.

- 🌍 Europa Experience (Erlebnis Europa), Unter den Linden 78, 10117 Berlin, Germany. 10:00-18:00. A permanent European exhibition in the German capital of Berlin. Free.

- 🌍 Europol, Eisenhowerlaan 73, 2517 KK The Hague, The Netherlands. National police handle nearly all law enforcement, but there is also an EU agency for these matters, the Europol. Visits are possible for groups of at least 20 when applied for well in advance.

- 🌍 Schengen. The town where the Schengen Agreement was signed. Contains a memorial and piece of the Berlin wall to commemorate the opening of borders, and the European Museum.

- European Parliament Information Offices. These offices are found throughout Europe, EU overseas territories and in Washington, DC. They can provide you with information about the EU, and host events for visitors to understand the EU better.

|

European Capital of Culture Upcoming cities designated as European Culture Capitals include: |

- European Capital of Culture. This EU program selects a couple of cities in member states to showcase European culture, with a good number of exhibitions and events.

- European Cultural Month (USA). Every May, the EU holds cultural events in the USA. You can hear Spanish folk music, see Shakespeare performed live, view some of the Dutch masters' paintings, take in avant-garde film from Romania, and taste Greek food.