Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (French: République Démocratique du Congo (or RDC); often shortened to DRC or D.R. Congo) is the largest and most populous country in Central Africa. It straddles the Equator and is surrounded by Angola to the southwest; Angola's Cabinda exclave and the Republic of the Congo to the northwest; the Central African Republic to the north; South Sudan to the northeast; Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania in the east from north to south; and Zambia to the southeast.

| WARNING: As of 9 October 2018, according to the WHO, 122 deaths due to the often fatal Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever have been reported in seven health zones in North Kivu Province (Beni, Butembo, Kalunguta, Mabalako, Masereka, Musienene and Oicha), and three health zones in Ituri Province (Mandima, Komanda and Tchomia). Travellers should seek medical advice before travel.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo remains one of the most underdeveloped countries in Africa and a significant portion of the DRC is not safe for any travel or sightseeing. In addition to active conflicts, the country has very limited health care and tourism facilities, even by African standards. More details can be found in the Stay safe section. The regions of North & South Kivu have been in a state of continuous conflict since the early 1990s. The North/South Kivu regions should be considered off limits by all visitors, except for aid/humanitarian workers who (and whose sponsor) are keenly aware of the risks. The north-eastern part of the country, just about everywhere north and east of the cities of Kisangani & Buma is unsafe due to active rebel groups responsible for low-level violence. Also the Kasaï region is very unsafe. In addition to the rebel groups and criminals, in 2018 there is still a severe risk of any public gathering turning violent because of the political situation. And if the situation were to deteriorate, leaving the country would probably be difficult. Keeping a stock of essential supplies is recommended. Those visiting for business, research, or international aid purposes should consult with their organization and seek expert guidance before planning a trip. Travellers visiting on their own should consult the advice of your embassy for any travel to the DRC. | |

Government travel advisories

| |

| (Information last updated Nov 2017) |

This country is also frequently called Congo-Kinshasa to distinguish it from its northwestern neighbor, the Republic of Congo (also known as "Congo-Brazzaville"). In the past, the DRC has been known as the Congo Free State, Belgian Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Congo-Leopoldville, or Zaire. On this and other guides within the DRC, "Congo" refers to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

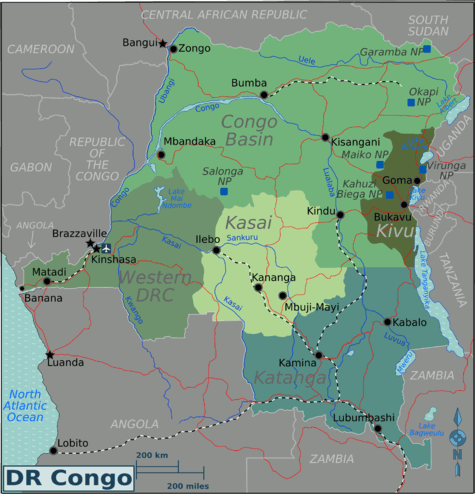

Regions

| Western DRC (Kinshasa) home to the capital Kinshasa and the nation's only port. Mostly tropical forests and grazing lands. |

| Katanga mostly fertile plateaus for agriculture & ranching, home to much of the country's recoverable minerals; de facto independent from 1960-1966 during the "Katanga Crisis" |

| Kasai significant diamond mining, not much else. |

| Kivu (Bukavu, Goma, Kahuzi-Biega National Park,Virunga National Park,) influenced by neighbouring Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda this region is known for its volcanoes, mountain gorillas, and, tragically, its unfathomable conflicts. |

| Congo Basin (Garamba National Park, Maiko National Park, Okapi Wildlife Reserve, Salonga National Park) the DRC's portion and the majority of the world's second largest jungle after the Amazon. |

Cities

Other destinations

Several parks are on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

- 🌍 Virunga National Park

- 🌍 Kahuzi-Biega National Park

- 🌍 Garamba National Park

- 🌍 Salonga National Park

- 🌍 Okapi Wildlife Reserve

- 🌍 Maiko National Park

Understand

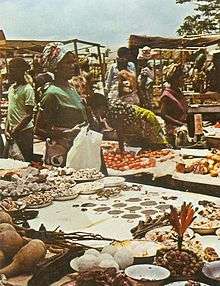

The Democratic Republic of the Congo remains a destination for only the most seasoned, hardcore African traveller. It is not a country for the casual tourist: the average backpacker, holidaymaker, and especially those seeking luxury safaris or organized cultural experiences. The DRC remains one of the least developed countries in Africa; its GDP per capita is the second lowest in the world, trailed only by Somalia. Largely covered by lush, tropical rainforest, the heart of the DRC is comparable to the Amazon (the only larger rainforest on Earth). The mighty Congo River forms the backbone of the country, carrying barges overflowing with Congolese (and the occasional adventurous Westerner) and merchants bringing their large pirogues laden with goods, fruit, and local bushmeat out to sell to those on the barges.

The country has faced a tragic, tumultuous history since colonization. It was plundered by Belgium's King Leopold II for rubber and palm oil, collected forcibly from the Congolese through unbelievably brutal means including hacking off hands for "crimes" such as production below the quota. The country and its central government fell apart just weeks after independence in 1960 and its leaders ever since have been far more preoccupied with quelling rebels and keeping the country together than with building infrastructure, improving education and healthcare, or doing anything else to improve the lives of the Congolese. Between 1994 and 2003, the bloodiest conflict since the end of World War II played out in the country's eastern jungles, with sporadic violence ongoing ever since. Millions of people have been displaced in the past 20 years, fleeing murder and mass rape carried out by rebels and hundreds of thousands remain in refugee camps to this day, sheltered by the largest UN peacekeeping mission (MONUC) in the world.

Those who do brave the elements to travel here are in for quite the adventure. In the east, volcanic peaks rise thousands of meters above the surrounding rainforest, often shrouded in mist. Hikers can climb up Mount Nyiragongo, looming above Goma, and spend the night on the rim above an active lava lake (one of just four worldwide!). In the jungles nearby, a small number of tourists each day are permitted to trek to families of gorillas—one of our species' closest living relatives. Along the mighty Congo River, a handful of travellers each year spend weeks floating hundreds of kilometres on barges loaded with cargo and Congolese. And don't forget to pick up masks and other handicrafts in lively markets across the country.

Geography

The DRC is truly vast. At 2,345,408 square kilometres (905,567 sq mi), it is larger than the combined areas of Spain, France, Germany, Sweden, and Norway—or nearly three and a half times the size of Texas.

The defining feature of the country is the second largest rainforest in the world. Rivers large and small snake throughout the country and with a poor road network remain the main means of transport to this day. The Congo River is the third largest river in the world measured by discharge—it even continues into the Atlantic, forming a submarine canyon roughly 50 mi (80 km) to the edge of the continental shelf! It also has the distinction of being one of the deepest rivers in the world with depths up to 220 m (720 ft). Because of the huge volume of water, depth, and rapids, the Congo River is home to a large number of endemic species. The Congo River "begins" at Boyoma Falls near Kisangani. Above these falls, the river is known as the Lualaba River, whose longest tributary extends into Zambia. The Obangui River forms the border between the DRC and CAR/Congo-Brazzaville before flowing into the Congo River.

The Albertine Rifft—a branch of the East African Rift—runs along the eastern border of the DRC. It is responsible for Lakes Tanganyika, Kivu, Edward, & Albert. The rift is flanked by a number of extinct volcanoes and two volcanoes that are still active today. The Rwenzori Mountains and Virunga Mountains along the border with Rwanda are quite scenic, rising in the midst of lush tropical forests and sometimes eerily shrouded in mist. Several peaks are over 4000m (13,000 feet). Mount Nyiragongo contains one of only four continuous lava lakes in the world.

The only part of the country not covered by lush forests is the south, around the Kasai Province, which contains mostly savannah and grasslands.

History

For several millennia, the land that now forms the DRC was inhabited by hundreds of small hunter/gatherer tribes. The landscape of dense, tropical forests and the rainy climate kept the population of the region low and prevented the establishment of advanced societies, and as a result few remnants of these societies remain today. The first and only significant political power was the Kongo Kingdom, founded around the 13th-14th centuries. The Kongo Kingdom, which spread across what is now northern Angola, Cabinda, Congo-Brazzaville, and Bas-Congo, became quite wealthy and powerful by trading with other African peoples in ivory, copperware, cloth, pottery, and slaves (long before Europeans arrived). The Portuguese made contact with the Kongos in 1483 and were soon able to convert the king to Christianity, with most of the population following. The Kongo Kingdom was a major source of slaves, who were sold in accordance to Kongo law and were mostly war captives. After reaching its height in the late 15th-early 16th century, the Kongo Kingdom saw violent competition for succession to the throne, war with tribes to the east, and a series of wars with the Portuguese. The Kongo Kingdom was defeated by the Portuguese in 1665 and effectively ceased to exist, although the largely ceremonial position of King of Kongo remained until the 1880s and "Kongo" remained the name of a loose collection of tribes around the Congo River delta. Kivu and the areas near Uganda, Rwanda, & Burundi were a source of slaves to Arab merchants from Zanzibar. The Kuba Federation, in southern DRC, was isolated enough to avoid slaving and even repel Belgian attempts to make contact with them beginning in 1884. After its peak of power in the early 19th century, however, the Kuba Federation broke apart by 1900. Elsewhere, only small tribes and short-lived kingdoms existed.

The land that is now the DRC was the last region of Africa to be explored by Europeans. The Portuguese never managed to travel more than a one to two hundred kilometres from the Atlantic coast. Dozens of attempts were made by explorers to travel up the Congo River, but rapids, the impenetrable jungle around them, tropical diseases, and hostile tribes prevented even the most well-equipped parties from travelling beyond the first cataract 160 km inland. Famed British explorer Dr Livingstone began exploring the Lualaba River, which he thought connected to the Nile but is actually the upper Congo, in the mid-1860s. After his famous meeting with Henry Morton Stanley in 1867, Livingstone travelled down the Congo River to Stanley Pool, which Kinshasa & Brazzaville now border. From there, he travelled overland to the Atlantic.

In Belgium, the zealous King Leopold II desperately wanted Belgium to obtain a colony to keep up with other European powers, but was repeatedly thwarted by the Belgian government (he was a Constitutional monarch). Finally, he decided he would obtain a colony himself as an ordinary citizen and organized a "humanitarian" organization to establish a purpose to claim the Congo, and then set up several shell companies to do so. Meanwhile, Stanley sought a financier for his dream project—a railway past the Congo River's lower cataracts, which would allow steamers on the upper 1,000 mile section of the Congo and open up the wealth of the "Heart of Africa". Leopold found a match in Stanley, and tasked him with building a series of forts along the upper Congo River and buying sovereignty from tribal leaders (or killing those unwilling). Several forts were built on the upper Congo, with workers & materials travelling from Zanzibar. In 1883, Stanley managed to travel overland from the Atlantic to Stanley Pool. When he got upriver, he discovered that a powerful Zanzibari slaver got wind of his work and captured the area around the Lualaba River, allowing Stanley to build his final fort just below Stanley Falls (site of modern Kisangani).

Congo Free State

When the European powers divided Africa amongst themselves at the Conference of Berlin in 1885, Under the umbrella of the Association internationale du Congo, Leopold, the sole shareholder, formally gained control of the Congo. The Congo Free State was established, containing all of the modern DRC. No longer needing the AIC, Leopold replaced it with a group of friends and commercial partners and quickly set about to tap the riches of the Congo. Any land not containing a settlement was deemed property of the Congo, and the state was divided into a private zone (exclusive property of the State) and a Free Trade Zone where any European could buy a 10-15 year land lease and keep all income from their land. Afraid of Britain's Cape Colony annexing Katanga (claiming the right to it wasn't exercised by Congo), Leopold sent the Stairs Expedition to Katanga. When negotiations with the local Yeke Kingdom broke down, the Belgians fought a short war which ended with the beheading of their king. Another short war was fought in 1894 with the Zanzibari slavers occupying the Lualaba River.

When the wars ended, the Belgians now sought to maximize profits from the regions. The salaries of administrators were reduced to a bare minimum with a rewards system of large commissions based on their district profits, which was later replaced with a system of commissions at the end of administrators' service dependent on the approval of their superiors. People living in the "Private Domain" owned by the state were forbidden from trading with anyone but the state, and were required to supply set quotas of rubber and ivory at a low, fixed price. Rubber in the Congo came from wild vines and workers would slash these, rub the liquid rubber on their bodies, and have it scraped off in a painful process when it hardened. The wild vines were killed in the process, meaning they became fewer and more difficult to find as rubber quotas rose.

The government's Force Publique enforced these quotas through imprisonment, torture, flogging, and the raping and burning of disobedient/rebellious villages. The most heinous act of the FP, however, was the taking of hands. The punishment for failing to meet rubber quotas was death. Concerned that the soldiers were using their precious bullets on sport hunting, the command required soldiers to submit one hand for every bullet used as proof they had used the bullet to kill someone. Entire villages would be surrounded and inhabitants murdered with baskets of severed hands being returned to commanders. Soldiers could get bonuses and return home early for returning more hands than others, while some villages faced with unrealistic rubber quotas would raid neighbouring villages to collect hands to present to the FP in order to avoid the same fate. Rubber prices boomed in the 1890s, bringing great wealth to Leopold and the whites of Congo, but eventually low-cost rubber from the Americas and Asia decreased prices and the operation in the CFS became unprofitable.

By the turn of the century, reports of these atrocities reached Europe. After a few years of successfully convincing the public that these reports were isolated incidents and slander, other European nations began investigating the activities of Leopold in the Congo Free State. Publications by noteworthy journalists and authors (like Conrad's Heart of Darkness and Doyle's The Crime of the Congo) brought the issue to the European public. Embarrassed, the government of Belgium finally annexed the Congo Free State, took over Leopold's holdings, and renamed the state Belgian Congo (to differentiate from French Congo, now Republic of the Congo). No census was ever taken, but historians estimate around half of the Congo's population, up to 10 million people, was killed between 1885 and 1908.

Belgian Congo

Aside from eliminating forced labour and the associated punishments, the Belgian government didn't make significant changes at first. To exploit the Congo's vast mineral wealth, the Belgians began construction of roads and railroads across the country (most of which remain, with little upkeep over the century, today). The Belgians also worked to give the Congolese access to education and health care. During WWII, the Congo remained loyal to the Belgian government in exile in London and sent troops to engage Italians in Ethiopia and Germans in East Africa. The Congo also became one of the world's main suppliers of rubber and ores. Uranium mined in Belgian Congo was sent to the U.S. and used in the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended the Pacific War.

After WWII, the Belgian Congo prospered and the 1950s were some of the most peaceful years in the Congo's history. The Belgian government invested in health care facilities, infrastructure, and housing. Congolese gained the right to buy/sell property and segregation nearly vanished. A small middle class even developed in the larger cities. The one thing the Belgians did not do was prepare an educated class of black leaders and public servants. The first elections open to black voters and candidates were held in 1957 in the larger cities. By 1959, the successful independence movements of other African countries inspired the Congolese and calls for independence grew louder and louder. Belgium did not want a colonial war to retain control of the Congo and invited a handful of Congolese political leaders for talks in Brussels in January 1960. The Belgians had in mind a 5-6 year transition plan to hold parliamentary elections in 1960 and gradually give administrative responsibility over to the Congolese with independence in mid-1960. The carefully crafted plan was rejected by the Congolese representative and the Belgians eventually conceded to hold elections in May and grant a hasty independence on 30 June. Regional and national political parties emerged with once-jailed leader Patrice Lumumba elected Prime Minister and head of the government.

Independence was granted to the "Republic of the Congo" (the same name neighbouring French colony Middle Congo adopted) on 30 June 1960. The day was marked by a sneer and verbal assault directed at the Belgian king after praising the genius of King Leopold II. Within weeks of independence, the army rebelled against white officers and increasing violence directed at the remaining whites forced nearly all 80,000 Belgians to flee the country.

Congo Crisis

After independence on 30 June 1960, the country quickly fell apart. The region of South Kasai declared independence on 14 June and the region of Katanga declared independence on 11 July under strongman Moise Tshombe. While not a puppet of Belgium, Tshombe was greatly helped by Belgian financial and military aid. Katanga was essentially a neo-colonial state backed by Belgium and the interests of Belgian mining companies. On 14 July, the UN Security Council passed a resolution authorizing a UN peacekeeping force, and for Belgium to withdraw remaining troops from the Congo. The Belgian troops left, but many officers stayed as paid mercenaries and were key in warding off the Congolese army's attacks (which were poorly-organized and were guilty of mass killings and rape). President Lumumba turned to the USSR for help, receiving military aid and 1,000 Soviet advisers. A UN force arrived to keep the peace, but did little initially. South Kasai was recaptured after a bloody campaign in December 1961. European mercenaries arrived from all around Africa and even from Europe to help the Katangan army. The UN force attempted to round up and repatriate mercenaries, but didn't make an impact. The UN mission was eventually changed to reintegrate Katanga into Congo with force. For over a year UN & Katanga forces fought in various clashes. UN forces surrounded and captured the Katanga capital Elisabethville (Lubumbashi) in December 1962. By January 1963, Tshombe was defeated, the last of the foreign mercenaries fled to Angola, and Katanga was reintegrated into the Congo.

Meanwhile, in Leopoldville (Kinshasa), relations between Prime Minister Lumumba and President Kasa-Vubu, of opposing parties, grew increasingly tense. In September 1960, Kasa-Vubu dismissed Lumumba from his Prime Minister position. Lumumba challenged the legality of this and dismissed Kasa-Vubu as President. Lumumba, who wanted a socialist state, turned to the USSR to ask for help. On September 14—just two and a half months after independence—Congolese Army Chief of Staff General Mobutu was pressured to intervene, launching a coup and placing Lumumba under house arrest. Mobutu had received money from the Belgian and US embassies to pay his soldiers and win their loyalty. Lumumba escaped and fled to Stanleyville (Kisangani) before being captured and taken to Elizabethville (Lubumbashi) where he was publicly beaten, disappeared, and was announced dead 3 weeks later. It was later revealed that he was executed in January 1961 in the presence of Belgian & US officials (who had both tried to kill him covertly ever since he asked the USSR for aid) and that the CIA and Belgium were complicit in his execution.

President Kasa-Vubu remained in power and Katanga's Tshombe eventually became Prime Minister. Lumumbist and Maoist Pierre Mulele led a rebellion in 1964, successfully occupying two thirds of the country, and turned to Maoist China for help. The US and Belgium once again got involved, this time with a small military force. Mulele fled to Congo-Brazzaville, but would later be lured back to Kinshasa by a promise of amnesty by Mobutu. Mobutu reneged on his promise, and Mulele was publicly tortured, his eyes gouged out, genitals cut off, and limbs amputated one by one while still alive; his body was then dumped in the Congo River.

The whole country saw widespread conflict and rebellion between 1960 and 1965, leading to the naming of this period the "Congo Crisis"

Mobutu

General Mobutu, a sworn anti-communist, befriended the US and Belgium in the height of the Cold War and continued to receive money to buy his soldiers' loyalty. In November 1965, Mobutu launched a coup, with U.S. & Belgian support behind the scenes, during yet another power struggle between the President and Prime Minister. Claiming that "politicians" had taken five years to ruin the country, he proclaimed "For five years, there will be no more political party activity in the country." The country was placed in a state of emergency, Parliament was weakened and soon eliminated, and independent trade unions abolished. In 1967, Mobutu established the only permitted political party (until 1990), the Popular Movement of the Revolution (MPR), which soon merged with the government so that the government effectively became a function of the party. By 1970, all threats to Mobutu's power were eliminated and in the presidential election he was the only candidate and voters were given the choice of green for hope or red for chaos (Mobutu... green... won with 10,131,699 to 157). A new constitution drafted by Mobutu and his cronies was approved by 97%.

In the early 1970s, Mobutu began a campaign known as Authenticité, which continued the nationalist ideology begun in his Manifesto of N’Sele in 1967. Under Authenticité, Congolese were ordered to adopt African names, men gave up Western suits for the traditional abacost, and geographical names were changed from colonial to African ones. The country became Zaire in 1972, Leopoldville became Kinshasa, Elisabethville became Lubumbashi, and Stanleyville became Kisangani. Most impressive of all, Joseph Mobuto became Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga ("The all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake."), or simply Mobutu Sese Seko. Among other changes, all Congolese were declared equal and hierarchical forms of address were eliminated, with Congolese required to address others as "citizen" and foreign dignitaries were met with African singing and dancing rather than a Western-style 21-gun salute.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, the government remained under the tight grip of Mobutu, who constantly shuffled political and military leaders to avoid competition, while the enforcement of Authenticité precepts waned. Mobutu gradually shifted in methods from torturing and killing rivals to buying them off. Little attention was paid to improving the life of Congolese. The single-party state essentially functioned to serve Mobutu and his friends, who grew disgustingly wealthy. Among Mobutu's excesses included a runway in his hometown long enough to handle Concorde planes which he occasionally rented for official trips abroad and shopping trips in Europe; he was estimated to have over US$5 billion in foreign accounts when he left office. He also attempted to build a cult of personality, with his image everywhere, a ban on media from saying any other government official by name (only title), and introduced titles like "Father of the Nation," "Saviour of the People," and "Supreme Combatant." Despite his Soviet-style single party state and authoritarian governance, Mobutu was vocally anti-Soviet, and with the fear of Soviet puppet governments rising in Africa (such as neighbouring Angola) the US and other Western powers continued providing economic aid and political support to the Mobutu regime.

When the Cold War waned, international support for Mobutu gave way to criticism of his rule. Covertly, domestic opposition groups began to grow and the Congolese people began to protest the government and the failing economy. In 1990, the first multi-party elections were held, but did little to effect change. Unpaid soldiers began rioting and looting Kinshasa in 1991 and most foreigners were evacuated. Eventually, a rival government arose from talks with the opposition, leading to a stalemate and dysfunctional government.

First and Second Congo Wars

By the mid-1990s, it was clear Mobutu's rule was nearing an end. No longer influenced by Cold War politics, the international community turned against him. Meanwhile, the economy of Zaire was in shambles (and remains little improved to this day). The central government had a weak control of the country and numerous opposition groups formed and found refuge in Eastern Zaire—far from Kinshasa.

The Kivu region was long home to ethnic strife between the various 'native' tribes and the Tutsis who were brought by the Belgians from Rwanda in the late 19th century. Several small conflicts had occurred since independence, resulting in thousands of deaths. But when the 1994 Rwandan genocide took place in neighbouring Rwanda, over 1.5 million ethnic Tutsi and Hutu refugees flowed into Eastern Zaire. Militant Hutus—the main aggressors in the genocide—began attacking both Tutsi refugees and the Congolese Tutsi population (the Banyamulenge) and also formed militias to launch attacks into Rwanda in hopes of returning to power there. Not only did Mobutu fail to stop the violence, but supported the Hutus for an invasion of Rwanda. In 1995, the Zairian Parliament ordered the return of all people of Rwandan or Burundian descent to return to be repatriated. The Tutsi-led Rwandan government, meanwhile, began to train and support Tutsi militias in Zaire.

In August 1996, fighting broke out and the Tutsis residing in the Kivu provinces began a rebellion with the goal of gaining control of North & South Kivu and fighting Hutu militias still attacking them. The rebellion soon gained support of the locals and collected many Zairian opposition groups, which eventually united as the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL) with the goal of ousting Mobutu. By the end of the year, with help from Rwanda & Uganda, the rebels had managed to control a large section of Eastern Zaire that protected Rwanda & Uganda from Hutu attacks. The Zairian army was weak and when Angola sent troops in early 1997, the rebels gained the confidence to capture the rest of the country and oust Mobutu. By May, the rebels were close to Kinshasa and captured Lubumbashi. When peace talks between sides broke down, Mobutu fled and AFDL leader Laurent-Desire Kabila marched into Kinshasa. Kabila changed the country's name to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, attempted to restore order, and expelled foreign troops in 1998.

A mutiny broke out in Goma in August 1998 among Tutsi soldiers and a new rebel group formed, taking control of much of the Eastern DRC. Kabila turned to Hutu militias to help suppress the new rebels. Rwanda saw this as an attack on the Tutsi population and sent troops across the border for their protection. By the end of the month, the rebels held much of the Eastern DRC along with a small area near the capital, including the Inga Dam which allowed them to shut off electricity to Kinshasa. When it looked certain Kabila's government and the capital Kinshasa would fall to the rebels, Angola, Namibia, & Zimbabwe agreed to defend Kabila and troops from Zimbabwe arrived just in time to protect the capital from a rebel attack; Chad, Libya, & Sudan also sent troops to help Kabila. As a stalemate approached, the foreign governments involved in fighting in the DRC agreed to a ceasefire in January 1999, but since the rebels weren't a signatory, fighting continued.

In 1999, the rebels broke up into numerous factions aligned along ethic or pro-Uganda/pro-Rwanda lines. A peace treaty among the six warring states (DRC, Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Rwanda and Uganda) and one rebel group was signed in July and all agreed to end fighting and track down and disarm all rebel groups, especially ones associated with the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Fighting continued as pro-Rwanda & pro-Uganda factions turned on each other and the UN authorized a peacekeeping mission (MONUC) in early 2000.

In January 2001, President Laurent Kabila was shot by a bodyguard and later died. He was replaced by his son Joseph Kabila. The rebels continued to break up into smaller factions and fought each other in addition to the DRC & foreign armies. Many rebels managed to gain funds through the smuggling of diamonds and other "conflict minerals" (like copper, zinc, & coltan) from the regions they occupied, many times through forced and child labor in dangerous conditions. The DRC signed peace treaties with Rwanda & Uganda in 2002. In December 2002, the main factions signed the Global and All-Inclusive Agreement to end the fighting. The agreement established a Transitional DRC government that would reunify the country, integrate & disarm rebel factions, and hold elections in 2005 for a new constitution & politicians with Joseph Kabila remaining president. The UN peacekeeping force grew much larger and was tasked with disarming rebels, many of which retained their own militias long after 2003. Conflict remains in North & South Kivu, Ituri, & northern Katanga provinces.

During the course of fighting, the First Congo War resulted in 250,000-800,000 dead. The Second Congo War resulted in over 350,000 violent deaths (1998-2001) and 2.7-5.4 million "excess deaths" as a result of starvation and disease among refugees due to the war (1998-2008), making it the deadliest conflict in the world since the end of World War Two.

Modern DRC

Joseph Kabila remained president of a transitional government until nationwide elections were held in 2006 for a new Constitution, Parliament, & President with major financial and technical support from the international community. Kabila won (and was re-elected in 2011). While corruption has been greatly reduced and politics have become more inclusive of minority political views, the country remains little improved from its condition at the end of Mobutu's rule. The DRC has the dubious distinction of having the lowest or second-lowest GDP per capita in the world (only Somalia ranks lower) and the economy remains poor. China has sought a number of mining claims, many of which are paid for by building infrastructure (railroads, roads) and facilities like schools & hospitals. The UN and many NGOs have a very large presence in the Kivu provinces, but despite a large amount of aid money, many still live in refugee camps and survive on foreign/UN aid. Fighting in Kivu & Ituri waned by the end of the decade, although many former militia members remain militant. Few have been tried and convicted for war crimes, although many former rebels leaders are accused of crimes against humanity & the use of child soldiers.

Soldiers formerly members of a militia that fought in Kivu from 2006 until a peace agreement in 2009 mutinied in April 2012 and a new wave of violence followed as they took control of a large area along the Uganda/Rwanda borders. Rwanda has been accused of backing this M23 movement and the UN is investigating their possible involvement.

Climate

The country straddles the Equator, with one-third to the north and two-thirds to the south. As a result of this equatorial location, the Congo experiences large amounts of precipitation and has the highest frequency of thunderstorms in the world. The annual rainfall can total upwards of 80 inches (2,032 mm) in some places, and the area sustains the second largest rain forest in the world (after that of the Amazon). This massive expanse of lush jungle covers most of the vast, low-lying central basin of the river, which slopes toward the Atlantic Ocean in the west. This area is surrounded by plateaus merging into savannahs in the south and southwest, by mountainous terraces in the west, and dense grasslands extending beyond the Congo River in the north. High, glaciated mountains are found in the extreme eastern region.

Read

- Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad. A short novel published in 1903 based on the experiences of Conrad while working in the Congo Free State.

- Through the Dark Continent by Henry Morton Stanley. An 1878 book documenting his trip down the Congo River.

- King Leopold's Ghost by Adam Hochschild. A non-fiction popular history book which examines the activities of Leopold and the men who ran the Congo Free State. A best-seller with 400,000 copies printed since publication in 1998. It is the basis of a 2006 documentary of the same name.

- Blood River: A Journey to Africa's Broken Heart by Tim Butcher. The author carefully retraces the route of Stanley's expedition in Through the Dark Continent and describes the challenges he faces.

- Dancing in the Glory of Monsters by Jason Stearns. Written by a member of the UN panel investigating Congolese rebels, this is a meticulously researched yet accessible account of the Congo wars.

People

More than 200 ethnic groups live in the Democratic Republic of Congo, including the Kongo, Mongo, Mangbetu Azande, and Luba who constitute 45% of the population of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Holidays

- January 1 - New Year's Day

- January 4 - Martyrs Day

- Easter - moveable

- May 17 - Liberation Day

- June 30 - Independence Day

- August 1 - Parents Day

- November 17 - Army Day

- December 25 - Christmas

- December 30 - St. Paul's Day

Get in

Entry requirements

Citizens of Burundi, Rwanda and Zimbabwe can enter the DRC visa free for up to 90 days. Citizens of Kenya, Mauritius and Tanzania can obtain a visa on arrival, valid for only 7 days. Everyone else travelling to the Congo for any purpose will need a visa. You can find the visa requirements on the Interior Ministry website (in French). However, getting a visa—like most government services—isn't straightforward and can be a messy process, with different officials telling you different stories in different places around the country and at different embassies/consulates worldwide. And then there's immigration officials trying to get more money out of you for their own gain. What follows are the requirements that seem to be in place as of June 2012, although you may hear stories telling you otherwise.

If arriving by air (Kinshasa or Lubumbashi), you will need to have a visa before arrival and proof of yellow fever vaccination. Visas on arrival are not issued, or at least not commonly enough that you risk being placed on the next plane back. You should also have one passport-sized photograph, and evidence that you have sufficient funds to cover your stay, which includes evidence of a hotel reservation. The requirements and costs for visas vary from embassy to embassy, with some requiring a letter of invitation, others an onward air ticket, proof of funds for travel, and others nothing beyond an application. If planning to get a visa in a third country (e.g.: an American arriving by air from Ethiopia), wait for a visa before booking the airfare, since DRC embassies in some African countries only issue visas to citizens or residents of that country.

As for arriving overland, you're best off if your home country doesn't have a DRC embassy (such as Australia & New Zealand) in which case you can apply for a visa in neighbouring countries without too much trouble. If your passport is from a country with a DRC embassy then embassies in neighbouring countries (Uganda, Rwanda, etc.) may tell you that you can only apply for a visa in your country of citizenship or residence.

If you're entering the DRC from Uganda or Rwanda (especially at Goma), the visa process seems different for everyone. You can apply for a visa at the embassies in Kigali, Kampala, or Nairobi with a 1-7 day turnaround for US$50–80. As recently as 2011, you could apply for a transit visa at the border relatively hassle-free for US$35 (and maybe a small "tip" for the official which goes away with persistence) with a yellow fever certificate and a passport-sized photo, although this no longer appears to be possible. Travellers trying to get a visa at the border have been asked for as much as US$500! (2012) It seems the actual cost depends on who's working at the post that day, your nationality, and how persistent you are, with US$100 seeming to be the real price, but many being told US$200–300 either as just the "fee" or a fee plus "tip" for the officials (which is what happens in the former situation anyways). These visas are either "transit" visas good for 7 days or visas only valid to visit the Goma and border areas. Given the bad security situation in North/South Kivu, you probably shouldn't venture outside Goma or the national parks anyways. If you visit Virunga National Park (official site), you can get a visa for USD50 and apply on-line or through your tour operator. If you can't get a visa at Goma for a reasonable price, you can travel south and try to cross at Bukavu and take a boat across the lake to Goma (do not go by road: too dangerous). Also, be sure if you cross the border to the DRC immigration post, you have officially left Uganda or Rwanda, so be sure you have a multiple-entry visa before leaving!

When exiting the country by air, there is a US$50 departure tax that you'll need to pay in cash at the airport. If you travel by boat from Kinshasa to Brazzaville, you officially need a special exit permit and a visa for Congo-Brazzaville. To save time/money/stress, you should probably contact your embassy in Kinshasa before taking the ferry.

By plane

The main gateway to the DRC is Kinshasa-N'djili airport (FIH IATA). Built in 1953, it hasn't had much in the way of upgrades and certainly doesn't rank among the continent's better airports.

From Africa: South African Airways, Kenyan Airways, Ethiopian Airlines, & Royal Air Maroc serve Kinshasa-N'djili multiple times a week from Johannesburg, Nairobi, Addis Ababa, & Casablanca (via Douala), respectively.

Other African airlines serving Kinshasa-N'Djili are: Afriqiyah Airways (Tripoli); Air Mali (Douala, Bamako); Benin Gulf Air (Cotonou, Pointe-Noire); Camair-co (Douala); CAA (Entebe); Ethiopian/ASKY (Brazzaville, Cotonou, Douala, Lagos, Lome); RwandAir (Kigali); TAAG Angola Airways (Luanda); Zambezi Airlines (Lusaka).

From Europe: Air France & Brussels Airlines have regular direct flights. Turkish Airlines will begin service from Istanbul in August 2012. You can also try booking travel through one of the major African airlines like Eithiopian, South African, Kenyan, or Royal Air Maroc.

The DRC's second city Lubumbashi (FBM IATA) has an international airport served by Ethiopian Airlines (Lilongwe, Addis Ababa), Kenya Airways (Harare, Nairobi), Korongo (Johannesburg), Precision Air (Dar es Salaam, Lusaka), & South African Express (Johannesburg).

Other airports with international service are Goma (GOM IATA) with service by CAA to Entebbe (Kampala) & Kisangani (FKI IATA) which is served by Kenya Airways from Nairobi.

By train

There is one line entering the DRC from Zambia. However, trains are very infrequent and unless you absolutely have to take the train for some reason, you should enter by road/air. The line reaches Lubumbashi and continuing to Kananga. The trains in the DRC are very old and the tracks are in various states of disrepair, with derailments frequent. Even when the trains do run, which may be weeks apart, they are overcrowded and lack just about every convenience you'd want (a/c, dining car, sleeper berths, etc.). Many of the lines in the southeast are no longer used. However Chinese companies who operate mines in the region are working to fix existing lines and build new ones, mainly for freight but some passenger service is likely in a few years.

By car

The roads as a whole are too rocky or muddy for cars without 4 wheel drive. Decent paved roads connect the Katanga region with Zambia and Kinshasa down to Matadi and Angola. Roads enter the DRC from Uganda, Rwanda, & Burundi, although travelling far past the border is very difficult and parts of the Eastern DRC remain unsafe. There are ferries to take vehicles across the Congo River from Congo-Brazzaville and it may be possible to find a ferry from the CAR to the remote, unpaved roads of the northern DRC. Do not entirely trust your map. Many display an unfortunate wishful thinking. Roads are frequently washed out by rains, or were simply never built in the first place. Ask a local or a guide whether or not a route is passable.

By bus

From Uganda to Congo via Bunagana Kisoro Border. There are many buses which operate daily between Bunagana /Uganda and Goma every day 07:00-13:00. Prices for the bus is USD5. A valid visa for both countries is required in either direction. Entry and exit procedures at Bunagana border are "easy" and straight forward, and people are very helpful in assisting visitors to get through without troubles.

By boat

Passenger and VIP ferries also locally known as 'Carnot Rapide' operate daily between Brazzaville and Kinshasa roughly every two hours 08:00-15:00. Prices for the ferries are: USD15 for the passenger and USD25 for the VIP ferry (Carnot Rapide). The latter is recommended as these are brand new boats and not cramped. A valid visa for both countries is required in either direction as well as (at least "officially") a special permit. The bureaucracy at either end require some time. Entry and exit procedures in Brazzaville are "easy" and straight forward and people are very helpful in assisting to get through without troubles. In contrast, these procedures are a bit difficult in Kinshasa and depend much on whether you are an individual traveller or assisted by an organisation or an official government representative.

There are also speed boats to hire, either in a group or alone (price!), however, it is not advisable to book them as they really speed across the river along the rapids.

Get around

By plane

Due to the immense size of the country, the terrible state of the roads and the poor security situation, the only way to get around the country quickly is by plane. This is not to say that it's safe — Congolese planes crash with depressing regularity, with eight recorded crashes in 2007 alone — but it's still a better alternative to travelling overland or by boat.

The largest and longest-operating carrier is Compagnie Africain d'Aviation, with service to Goma, Kananga, Kindu, Kinshasa-N'djili, Kisangani, Lubumbashi, Mbandaka, Mbuji-Maya, & Entebbe(Kampala), Uganda.

Formed in 2011, Stellar Airlines operates one Airbus A320 plane between Kinshasa-N'djili and Goma and Lubumbashi.

FlyCongo was formed in 2012 from the remnants of former national airline Hewa Bora, operating from Kinshasa-N'djili to Gemena, Goma, Kisangani, Lubumbashi, & Mbandaka.

Air Kasaï operates from Kinshasa-N'Dolo to Beni, Bunia, Goma, & Lubumbashi.

Congo Express was formed in 2010 and flies only between Lubumbashi and Kinshasa.

Wimbi Dira Airways was once the second-largest carrier, but does not appear to be operating as of June 2012. Others that may or may not be operating are: Air Tropiques, Filair, Free Airlines, and Malift Air all operating out of Kinshasa-N'Dolo airport.

By truck

As smaller vehicles are unable to negotiate what remains of the roads, a lot of travel in the Congo is done by truck. If you go to a truck park, normally near the market, you should be able to find a truck driver to take you where ever you want, conflict zones aside. You travel on top of the load with a large number of others. If you pick a truck carrying bags of something soft like peanuts it can be quite comfortable. Beer trucks are not. If the trip takes days then comfort can be vital, especially if the truck goes all night. It helps to sit along the back, as the driver will not stop just because you want the toilet. The cost has to be negotiated so ask hotel staff first and try not to pay more than twice the local rate. Sometimes the inside seat is available. Food can be bought from the driver, though they normally stop at roadside stalls every 5/6 hours. Departure time are normally at the start or end of the day, though time is very flexible. It helps to make arrangements the day before. It is best to travel with a few others. Women should never ever travel alone. Some roads have major bandit problems so check carefully before going.

At army checkpoints locals are often hassled for bribes. Foreigners are normally left alone, but prepare some kind of bribe just in case. By the middle of the afternoon the soldiers can be drunk so be very careful and very polite. Never lose your temper.

By ferry

A ferry on the Congo River operates, if security permits, from Kinshasa to Kisangani, every week or two. You can pick it up at a few stops en route, though you have to rush as it doesn't wait. A suitable bribe to the ferry boss secures a four bunk cabin and cafeteria food. The ferry consists of 4 or so barges are tied around a central ferry, with the barges used as a floating market. As the ferry proceeds wood canoes paddled by locals appear from the surrounding jungle with local produce - vegetables, pigs, monkeys, etc. - which are traded for industrial goods like medicine or clothes. You sit on the roof watching as wonderful African music booms out. Of course it is not clean, comfortable or safe. It is however one of the world's great adventures.

By train

The few trains which still operate in the DRC are in very poor condition and run on tracks laid by the Belgian colonial government over a half century ago. The rolling stock is very old and dilapidated. You are lucky to get a hard seat and even luckier if your train has a dining car (which probably has limited options that run out halfway through the trip). Expect the car to be overcrowded with many sitting on the roof. Trains in the DRC operate on an erratic schedule due to lack of funds or fuel and repairs/breakdowns that are frequent. On many lines, there can be 2–3 weeks between trains. If there's any upside, there haven't been too many deaths due to derailments (probably less than have died in airplane crashes in the DRC). There's really no way to book a train ride in advance; simply show up at the station and ask the stationmaster when the next train will run and buy a ticket on the day it leaves. The Chinese government in return for mining rights has agreed to construct US$9 billion in railroads and highways, but there is little to show for this as of 2012.

As of 2012, the following lines are in operation...but as mentioned above, that doesn't imply frequent service:

- Kinshasa-Matadi—Built in the 1890s by forced labor (of whom 7000 died), this line is the busiest in the country. There is possibly once or twice weekly service.

- Lubumbashi-Ilebo—Possible weekly service, with the journey taking 6–8 days. In 2007, the Chinese agreed to extend the line to Kinshasa, but current progress in unknown. Ilebo lies at the end of the navigable portion of the Kasai River, allowing travellers to transfer to ferry to reach Western DRC.

- Kamina-Kindu—Unusable after the war, this line has been rehabilitated. The line connects with the Lubumbashi-Ilebo line, so there may be trains running from Lubumbashi-Kindu.

- Kisangani-Ubundu—A portage line to bypass the Stanley Falls on the Congo, service only runs when there is freight to carry when a boat arrives at either end which may be once every 1–2 months. There are no passenger ferries from Ubundu to Kindu, but you may be able to catch a ride on a cargo boat.

- Bumba-Isiro—An isolated, narrow-gauge line in the northern jungles, service has restarted on a small western section from Bumba-Aketi (and possibly Buta). There were reports of trains running in the eastern section in 2008, but this part is most likely abandoned.

Lines that are most likely inoperable or very degraded/abandoned are:

- A branch of the Lubumbashi-Ilebo line that runs to the Angolan border. It once connected with Angola's Benguela railway and ran to the Atlantic until the 1970s when the Angolan side was destroyed by a civil war. The western half of the Benguela railway has been rehabilitated and may be operational to the DRC border in the future.

- The Kabalo-Kalemie line runs from the Kamina-Kindu line at Kabalo to Kalemie on Lake Tanganyika. The easternmost section has been abandoned. Although unlikely, there may be service on the western half of the line.

Talk

French is the lingua franca of the country and nearly everyone has a basic to moderate understanding of French. In Kinshasa and much of the Western DRC, nearly everyone is fluent in French with Kinshasa being the second or third largest French-speaking city in the world (depending on your source), although locals may be heard speaking Lingala amongst themselves. Much of the eastern half speaks Swahili as a regional language. The other major regional languages in the country are Kikongo and Tshiluba, and the Congo also has a wide range of smaller local languages. Like the regional languages, the local languages are mostly in the Bantu family. If you are travelling to the southwestern border near Angola you can find some Portuguese speakers.

See

The "Academie des Beaux-Arts" is often considered a touristic site and is in itself and with its gallery a good place to meet the famous artists of this country. Big names like Alfred Liyolo, Lema Kusa oder Roger Botembe are teaching here as well as the only purely abstract working artist Henri Kalama Akulez, whose private studio is worth a visit.

Do

Congo is the centre of popular African music. Try visiting a local bar or disco, in Bandal or Matonge (both in Kinshasa), if possible with live soukouss music, and just hit the dance floor!

Buy

There are some supermarkets in Gombe commune of Kinshasa that sell food and drinks, soap, kitchen devices and bazar: City Market, Peloustore, Kin Mart, Hasson's.

SIM cards and prepaid recharge for mobile phones are available in the street and at Ndjili airport, at a reasonable price.

Money

|

Exchange rates for Congolese franc As of January 2019:

Exchange rates fluctuate. Current rates for these and other currencies are available from XE.com |

The local currency is the Congolese franc, sometimes abbreviated FC and sometimes just with a capital F placed after the amount (ISO international currency code: CDF). The currency is freely convertible (but impossible to get rid of outside the country).

Banknotes are issued in denominations of FC50, 100, 200, 500, 1,000, 5,000, 10,000 and 20,000. The only Congolese bank notes in circulation in most places are the 50, 100, 200 and 500 franc notes. They are almost worthless, as the highest valued banknote (the 500 franc note) is worth only about US$0.55.

US dollars in denominations above US$2 are much preferred to francs. In contrast, US coins and one and two US dollar bills are considered worthless. If you pay in dollars, you will get change in francs. Though francs may sometimes come in bills so old they feel like fabric, US dollar bills must be crisp (less than 3 folds) and be printed in or after 2003, or they will not be accepted.

In some shops, the symbol FF is used to mean 1,000 francs.

MasterCard/Maestro ATMs are available now in Kinshasa at the "Rawbank" on boulevard du 30 Juin (Gombe District), and in Grand Hotel. It spits out US dollars. Visa card is also usable with "Procredit" bank ATMs in Kinshasa, avenue des Aviateurs, or outside in front of Grand Hotel (only US$20 and US$100 bills).

Eat

Congo has one national dish: moambe. It's made of eight ingredients (moambe is the Lingala word for eight): palm nuts, chicken, fish, peanuts, rice, cassave leaves, bananas and hot pepper sauce.

Drink

The usual soft drinks (called sucré in Congo) such as Coke, Pepsi and Mirinda are available in most places and are safe to drink. Local drinks like Vitalo are amazing. Traditional drinks like ginger are also common.

The local beer is based on rice, and tastes quite good. It comes in 75 cl bottles. Primus, Skol, Castel are the most common brands. Tembo, Doppel are the local dark beers.

In rural areas, you may try the local palm wine, an alcoholic beverage from the sap of the palm tree. It is tapped right from the tree, and begins fermenting immediately after collection. After two hours, fermentation yields an aromatic wine of up to 4% alcohol content, mildly intoxicating and sweet. The wine may be allowed to ferment longer, up to a day, to yield a stronger, more sour and acidic taste, which some people prefer.

Beware of the local gin. Sometimes unscrupulous vendors mix in methanol which is toxic and can cause blindness. Some people believe that the methanol is a by product of regular fermentation. This is not the case as regular fermentation can not yield methanol in toxic amounts.

Sleep

There are more and more hotels in Kinshasa, with smaller hotels available in Gombe and Ngaliema area. In many small towns the local church or monastery may have beds available. You may also encounter the occasional decaying colonial hotel. Not all are safe.

Stay safe

See also War zone safety and Tips for travel in developing countries.

.jpg)

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has seen more than its fair share of violence. A number of ongoing wars, conflicts, and episodes of fighting have occurred since independence, with sporadic, regional violence continuing today. As a result, significant sections of the country should be considered off-limits to travellers.

In the northeastern part of the country, the LRA (of child-soldier & 'Kony' fame) continues to roam the jungles near the border with the CAR/South Sudan/Uganda. Although a few areas very close to the Ugandan border are relatively safe to visit, travel anywhere north and east of Kisangani & Bumba is dangerous.

The regions of North & South Kivu have been in a state of continuous conflict since the early 1990s. The days of the notoriously bloody violence that occurred during the First and Second Congo Wars (during which 5 million died in fighting or through resulting disease/famine) officially ended with a peace treaty in 2003. However, low-level violence spurred by several warlords/factions has occurred ever since and this region is home to the largest UN peacekeeping mission in the world (as of 2012). Hundreds of thousands live in refugee camps near Goma. In April 2012, a new faction—"M23"—arose, led by Gen.Ntaganda (wanted by the ICC for war crimes) and has captured/attacked many towns in the region, where they are accused of killing civilians and raping women. This has been the most serious crisis since the end of war in 2003. In mid-July, they threatened to invade Goma to protect the Tutsi population there from "harassment"; the UN peacekeeping mission quickly responded that they would reposition 19,000 peacekeepers to protect Goma & nearby refugee camps. How serious the threat of fighting in Goma remains to be seen BBC report) The only safe areas in North/South Kivu are the cities of Goma & Bukavu and Virunga National Park, all on the Rwandan border.

The dangers to visitors are far beyond conflicts, though. After Somalia, the DRC is most likely the least developed country in Africa. The road network is pathetic. The country's roads are in very poor condition and travel over long distances by road can take weeks, especially during the wetter months. Even some of the country's "main" roads are little more than mud tracks that can only be travelled by 4x4 or 6x6 trucks. The DRC has just 2250 km of sealed roads, of which the UN considers only 1226 km to be in "good" condition. To put this in perspective, the road distance east-west across the country in any direction is over 2500 km (e.g. Matadi to Lubumbashi is 2700 by road)! Another comparison is that there are just 35 km of paved highway per 1 000 000 people—Zambia (one of the poorest African countries) and Botswana (one of the richest) have 580 km and 3427 km per 1 000 000 people, respectively. Public transportation is almost non-existent and the primary means of travel is catching a ride on an old, overloaded truck where several paying passengers are allowed to sit atop the cargo. This is very dangerous.

Congolese planes crash with depressing regularity, with eight recorded crashes in 2007 alone. Despite this, the risks of air travel remain on par with travel by road, barge, or rail. The notorious Hewa Bora airlines has gone out of business and the creation of a handful of new airlines between 2010 and 2012 should lead to improvement in the safety of air travel in the DRC. Avoid at all costs, old Soviet aircraft that are often chartered to carry cargo and perhaps a passenger or two and stick with the commercial airlines operating newer aircraft (listed above under "Get around/By plane"). If you are still fearful of getting on a Congolese plane and aren't as concerned about cost, you can try flying with a foreign carrier such as Kenyan Airways (which flies to Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, & Kisangani) or Ethiopian (Kinshasha, Lubumbashi). Just be sure to check the visa requirements to transit.

Travel by river boat or barge remains somewhat risky, although safer than by road. Overcrowded barges have sunk and aging boats have capsized travelling along the Congo River, resulting in hundreds of deaths. Before catching a ride, take a look at the vessel you will be boarding and if you don't feel safe, it is better to wait for the next boat, even if you must wait several days. Most of the country's rail network is in disrepair, with little maintenance carried out since the Belgians left. A few derailings have occurred, resulting in large numbers of casualties. Trains in the DRC are also overloaded, don't even think about joining the locals riding on the roof!

Crime is a serious problem across much of the country. During the waning years of Mobutu's rule, Kinshasa had one of the highest murder rates in the world and travel to Kinshasa was comparable to Baghdad during the Iraq War! While violence has subsided considerably, Kinshasa remains a high crime city (comparable to Lagos or Abidjan). Keep anything that can be perceived as valuable by a Congolese out of sight when in vehicles, as smash-and-grab crime at intersections occurs. Markets in larger cities are rife with pickpockets. Keep in mind that the DRC remains among the 3-4 poorest countries in Africa and compared to the locals, every white person is perceived as rich. Be vigilant of thieves in public places. If travelling in remote areas, smaller villages are usually safer than larger ones. Hotel rooms outside the biggest cities often don't have adequate safety (like flimsy locks on doors or ground-level windows that don't lock or have curtains).

Taking photos in public can be cause for suspicion. By some accounts, an official permit is needed to take photos in the DRC. Actually they will likely be difficult or impossible to find or obtain. Do not photograph anything that can be perceived as a national security threat, such as bridges, roadblocks, border crossings, and government buildings.

Additionally, the DRC has very poor health care infrastructure/facilities. Outside the capital Kinshasa, there are very few hospitals or clinics for sick or injured travellers to visit. If you are travelling on one of the country's isolated, muddy roads or along the Congo River, you could be over a week away from the nearest clinic or hospital! A number of tropical diseases are present—see "Stay healthy" below.

Stay healthy

See also: Tropical diseases, Malaria, Dengue fever, Yellow fever, & Mosquitoes.

Ebola Virus – a virus which killed 49 people in DRC during a three-month outbreak in 2014 – remains present in the equatorial forest region of Bas-Uele province (bordering Central African Republic/CAR). On 1 August 2018, the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of the Congo declared a new outbreak of Ebola virus disease in North Kivu and Ituri Provinces. Travellers should avoid eating bushmeat, avoid contact with persons that appear ill, practice good personal hygiene and seek medical advice before travel.

You will need a yellow fever vaccination in order to enter the country by air (this requirement is often ignored at land entry points, particularly the smaller ones). There are health officials at some major entry points, such as the airport in Kinshasa, who check this before you are allowed to enter.

Congo is malarial, although slightly less in the Kivu region due to the altitude, so use insect repellent and take the necessary precautions such as sleeping under mosquito nets. The riverside areas (such as Kinshasa) are quite prone to malaria.

If you need emergency medical assistance, it is advised that you go to your nation's embassy. The embassy doctors are normally willing and skilled enough to help. There are safe hospitals in Kinshasa, like "CMK" (Centre Medical de Kinshasa), which is private and was established by European doctors (a visit costs around US$20). Another private and non-profit hospital is Centre Hospitalier MONKOLE, in Mont-Ngafula district, with European and Congolese doctors. Dr Léon Tshilolo, a paediatrician trained in Europe and one of the African experts in sickle-cell anaemia, is the Monkole Medical Director.

Drink lots of water when outside. The heat and close proximity to the equator can easily give those not acclimated heatstroke after just a few hours outside without water. There are many pharmacies that are very well supplied but prices are a few times higher than in Europe.

Do not drink the tap water. Bottled water seems to be cheap enough, but sometimes hard to find for a good price.

Respect

Photography is officially illegal without an official permit which, last known was US$60. Even with this permit, photography is very difficult with the Congolese becoming extremely upset when photographed without permission or when one is taking a picture of a child. These confrontations can be easily diffused by apologizing profusely and not engaging in the argument. Sometimes a small bribe might be needed to "grease the wheels" as well.

Never under any circumstances photograph government buildings or structures. This includes but is not limited to police stations, presidential palaces, border crossings, and anywhere in the airport. You will be detained by police if caught and unable to bribe them for your transgression.

When motorcades pass, all vehicular traffic is expected to provide a clear path. Do not photograph these processions.

At dawn and dusk (c. 06:00 and 18:00 daily), the national flag is raised and lowered. All traffic and pedestrians are required to stop for this ceremony, with reports indicating that those who do not are detained by security personnel.

Connect