Zuo zhuan

The Zuo zhuan ([tswò ʈʂwân]; Chinese: 左傳; Wade–Giles: Tso chuan), generally translated The Zuo Tradition or The Commentary of Zuo, is an ancient Chinese narrative history that is traditionally regarded as a commentary on the ancient Chinese chronicle Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu 春秋). It comprises 30 chapters covering a period from 722 to 468 BC, and focuses mainly on political, diplomatic, and military affairs from that era. The Zuo zhuan is famous for its "relentlessly realistic" style, and recounts many tense and dramatic episodes, such as battles and fights, royal assassinations and murder of concubines, deception and intrigue, excesses, citizens' oppression and insurgences, and appearances of ghosts and cosmic portents.

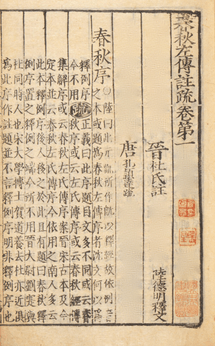

Zuo zhuan title page, Ming dynasty print (16th century) | |

| Author | (trad.) Zuo Qiuming |

|---|---|

| Country | Zhou dynasty (China) |

| Language | Classical Chinese |

| Subject | History of the Spring and Autumn period |

| Published | c. late 4th century BC |

| Zuo zhuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) "Zuo zhuan" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 左傳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 左传 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Zuo Tradition" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For many centuries, the Zuo zhuan was the primary text through which educated Chinese gained an understanding of their ancient history. Unlike the other two surviving Annals commentaries—the Gongyang and Guliang commentaries—the Zuo zhuan does not simply explain the wording of the Annals, but greatly expounds upon its historical background, and contains many rich and lively accounts of Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BC) history and culture. The Zuo zhuan is the source of more Chinese sayings and idioms than any other classical work, and its concise, flowing style came to be held as a paragon of elegant Classical Chinese. Its tendency toward third-person narration and portraying characters through direct speech and action became hallmarks of Chinese narrative in general, and its style was imitated by historians, storytellers, and ancient style prose masters for over 2000 years of subsequent Chinese history.

Although the Zuo zhuan has long been regarded as "a masterpiece of grand historical narrative", its early textual history is largely unknown, and the nature of its original composition and authorship have been widely debated. The "Zuo" of the title was traditionally believed to refer to one "Zuo Qiuming"—an obscure figure of the 5th century BC described as a blind disciple of Confucius—but there is little actual evidence to support this. Most scholars now generally believe that the Zuo zhuan was originally an independent work composed during the 4th century BC that was later rearranged as a commentary to the Annals.

Textual history

Creation

Notwithstanding its prominent position throughout Chinese history as the paragon of Classical Chinese prose, little is known of the Zuo zhuan's creation and early history. Bamboo and silk manuscripts excavated from late Warring States period (c. 300 BC) tombs—combined with analyses of the Zuo zhuan's language, diction, chronological references, and philosophical viewpoints—suggest that the composition of the Zuo zhuan was largely complete by 300 BC.[1] However, no pre-Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) source indicates that the Zuo zhuan had to that point been organized into any coherent form, and no texts from this period directly refer to the Zuo zhuan as a source, though a few mention its parent text Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu 春秋).[2] It seems to have had no distinct title of its own during this period, but was simply called Annals (Chunqiu) along with a larger group of similar texts.[2] In the 3rd century AD, the Chinese scholar Du Yu intercalated it with the Annals so that each Annals entry was followed by the corresponding narrative from the Zuo zhuan, and this became the received format of the Zuo zhuan that exists today.[3] Most scholars now generally believe that the Zuo zhuan was originally an independent work composed during the latter half of the 4th century BC—though probably incorporating some even older material[4]—that was later rearranged as a commentary to the Annals.[5]

Authorship

China's first dynastic history Records of the Grand Historian, completed by the historian Sima Qian in the early 1st century BC, refers to the Zuo zhuan as "Master Zuo's Spring and Autumn Annals" (Zuoshi Chunqiu 左氏春秋) and attributes it to a man named "Zuo Qiuming" (or possibly "Zuoqiu Ming").[6] According to Sima Qian, after Confucius' death his disciples began disagreeing over their interpretations of the Annals, and so Zuo Qiuming gathered together Confucius' scribal records and used them to compile the Zuo Annals in order to "preserve the true teachings."[7]

This "Zuo Qiuming" Sima Qian references was traditionally assumed to be the Zuo Qiuming who briefly appears in the Analects of Confucius (Lunyu 論語) when Confucius praises him for his moral judgment.[8][9] Other than this brief mention, nothing is concretely known of the life or identity of the Zuo Qiuming of the Analects, nor of what connection he might have with the Zuo zhuan.[10] This traditional assumption that the title's "Master Zuo" refers to the Zuo Qiuming of the Analects is not based on any specific evidence, and was challenged by scholars as early as the 8th century.[8] Even if he is the "Zuo" referenced in the Zuo zhuan's title, this attribution is questionable because the Zuo zhuan describes events from the late Spring and Autumn period (c. 771–476 BC) that the Zuo Qiuming of the Analects could not have known.[6]

Alternatively, a number of scholars, beginning in the 18th century, have suggested that the Zuo zhuan was actually the product of one Wu Qi (吳起; d. 381 or 378 BC), a military leader who served in the State of Wei and who, according to the Han Feizi, was from a place called "Zuoshi".[6] In 1792, the scholar Yao Nai wrote: "The text [Zuo zhuan] did not come from one person. There were repeated accretions and additions, with those of Wu Qi and his followers being especially numerous...."[11]

Commentary status

In the early 19th century, the Chinese scholar Liu Fenglu (劉逢祿; 1776–1829) initiated a long, drawn-out controversy when he proposed, by emphasizing certain discrepancies between it and the Annals, that the Zuo zhuan was not originally a commentary on the Annals.[12] Liu's theory was taken much further by the prominent scholar and reformer Kang Youwei, who argued that Liu Xin did not really find the "ancient script" version of the Zuo zhuan in the imperial archives, as historical records describe, but actually forged it as a commentary on the Annals.[13] Kang's theory was that Liu Xin—who with his father Liu Xiang, the imperial librarian, was one of the first to have access to the rare documents in the Han dynasty's imperial archives—took the Discourses of the States (Guoyu 國語) and forged it into a chronicle-like work to fit the format of the Annals in an attempt to lend credibility to the policies of his master, the usurper Wang Mang.[13][14]

Kang's theory was supported by several subsequent Chinese scholars in the late 19th century, but was contradicted by many 20th-century studies that examined it from many different perspectives.[14] In the early 1930s, the French Sinologist Henri Maspero performed a detailed textual study of the issue, concluding the Han dynasty forgery theory to be untenable.[14] The Swedish Sinologist Bernhard Karlgren, based on a series of linguistic and philological analyses he carried out in the 1920s, concluded that the Zuo zhuan is a genuine ancient text "probably to be dated between 468 and 300 BC."[13] While Liu's hypothesis that the Zuo zhuan was not originally an Annals commentary has been generally accepted, Kang's theory of Liu Xin forging the Zuo zhuan is now considered discredited.[15]

Manuscripts

The oldest surviving Zuo zhuan manuscripts are six fragments that were discovered among the Dunhuang manuscripts in the early 20th century by the French Sinologist Paul Pelliot and are now held at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.[3] Four of the fragments date to the Six Dynasties period (3rd to 6th centuries), while the other two date to the early Tang dynasty (7th century).[3] The oldest known complete Zuo zhuan manuscript is the "ancient manuscript scroll" preserved at the Kanazawa Bunko Museum in Yokohama, Japan.[16]

Content and style

Content

The Zuo zhuan recounts the major political, military, and social events of the Spring and Autumn period from the perspective of the State of Lu, and is famous "for its dramatic power and realistic details".[17] It contains a variety of tense and dramatic episodes: battles and fights, royal assassinations and murder of concubines, deception and intrigue, excesses, citizens' oppression and insurgences, and appearances of ghosts and cosmic portents.[15]

The Zuo zhuan originally contained only its core content, without any content from or references to the Spring and Autumn Annals. In the 3rd century AD, the Chinese scholar Du Yu intercalated the Annals into the Zuo zhuan, producing the received format that exists today. The entries follow the strict chronological format of the Annals, so interrelated episodes and the actions of individual characters are sometimes separated by events that occurred in the intervening years.[18] Each Zuo zhuan chapter begins with the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu) entry for the year, which is usually terse and brief, followed by the Zuo zhuan content for that year, which often contains long and detailed narratives.

The following entry, though unusually short, exemplifies the general format of all Zuo zhuan entries.

Annals

三十有一年,春,築臺于郎。夏,四月,薛伯卒。築臺于薛。六月,齊侯來獻戎捷。秋,築臺于秦。冬,不雨。

In the 31st year, in spring, a terrace was built in Lang. In summer, in the 4th month, the Liege of Xue died. A terrace was built at Xue. In the 6th month, the Prince of Qi came to present spoils from the Rong. In autumn, a terrace was built in Qin. In winter, it did not rain.

(Zuo)

三十一年,夏,六月,齊侯來獻戎捷,非禮也。凡諸侯有四夷之功,則獻于王,王以警于夷,中國則否。諸侯不相遺俘。

In the 31st year, in summer, in the 6th month, the Prince of Qi came here to present spoils from the Rong: this was not in accordance with ritual propriety. In all cases when the princes achieve some merit against the Yi of the four directions, they present these spoils to the king, and the king thereby issues a warning to the Yi. This was not done in the central domains. The princes do not present captives to one another.

| Text

(Chinese) |

Ruler of the State of Lu | Reign Duration (Years) |

Period of Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 隱公 | Duke Yin of Lu (魯隱公) | 11 | 722 – 712 BC |

| 桓公 | Duke Huan of Lu (魯桓公) | 18 | 711 – 694 BC |

| 莊公 | Duke Zhuang of Lu (魯莊公) | 32 | 693 – 662 BC |

| 閔公 | Duke Min of Lu (魯閔公) | 2 | 661 – 660 BC |

| 僖公 | Duke Xi of Lu (魯僖公) | 33 | 659 – 627 BC |

| 文公 | Duke Wen of Lu (魯文公) | 18 | 626 – 609 BC |

| 宣公 | Duke Xuan of Lu (魯宣公) | 18 | 608 – 591 BC |

| 成公 | Duke Cheng of Lu (魯成公) | 18 | 590 – 573 BC |

| 襄公 | Duke Xiang of Lu (魯襄公) | 31 | 572 – 542 BC |

| 昭公 | Duke Zhao of Lu (魯昭公) | 32 | 541 – 510 BC |

| 定公 | Duke Ding of Lu (魯定公) | 15 | 509 – 495 BC |

| 哀公 | Duke Ai of Lu (魯哀公) | 27 | 494 – 468 BC |

Style

Zuo zhuan narratives are famously terse and succinct—a quality that was admired and imitated throughout Chinese history—and usually focus either on speeches that illustrate ethical values, or on anecdotes in which the details of the story illuminate specific ethical points.[20] Its narratives are characterized by parataxis, where clauses are juxtaposed without much verbal indication of their causal relationships with each other.[18] On the other hand, the speeches and recorded discourses of the Zuo zhuan are frequently lively, ornate, and verbally complex.[18]

Themes

Although the Zuo zhuan was probably not originally a commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu 春秋)—a work which was traditionally viewed as a direct creation of Confucius—its basic philosophical outlook is also strongly Confucian in nature.[21] Its overarching theme is that haughty, evil, and stupid individuals generally bring disaster upon themselves, while those who are good, wise, and humble are usually justly rewarded.[21] The Confucian principle of "ritual propriety" or "ceremony" (lǐ 禮) is seen as governing all actions, including war, and to bring bad consequences if transgressed.[21] However, the observance of li is never shown as guaranteeing victory, and the Zuo zhuan includes many examples of the good and innocent suffering senseless violence.[21] Much of the Zuo zhuan's status as a literary masterpiece stems from its "relentlessly realistic portrayal of a turbulent era marked by violence, political strife, intrigues, and moral laxity".[21]

The narratives of the Zuo zhuan are highly didactic in nature, and are presented in such a way that they teach and illustrate moral principles.[22] The German Sinologist Martin Kern observed: "Instead of offering authorial judgments or catechistic hermeneutics, the Zuo zhuan lets its moral lessons unfold within the narrative itself, teaching at once history and historical judgment."[15] Unlike the Histories of Herodotus or the History of the Peloponnesian War of Thucydides—with which it is roughly contemporary—the Zuo zhuan's narration always remains in the third person perspective, and presents as a dispassionate recorder of facts.[18]

Battles

Several of the Zuo zhuan's most famous sections are those dealing with critical historical battles, such as the Battle of Chengpu and the Battle of Bi.[23]

The Battle of Chengpu, the first of the Zuo zhuan's great battles, took place in the summer of 632 BC at Chengpu (now Juancheng County, Shandong Province) in the State of Wey.[24] On one side were the troops of the powerful State of Chu, from what was then far southern China, led by the Chu prime minister Cheng Dechen.[24] They were opposed by the armies of the State of Jin, led by Chong'er, Duke of Jin, one of the most prominent and well known figures in the Zuo zhuan.[24] Chu suffered a disastrous defeat in the battle itself, and it resulted in Chong'er being named Hegemon (bà 霸) of the various states.[24]

己巳,晉師陳于莘北,胥臣以下軍之佐,當陳蔡;

On the day ji-si the Jin army encamped at [Chengpu]. The Jin commander Xu Chen, who was acting as assistant to the leader of the lower army, prepared to oppose the troops of Chen and Cai.

子玉以若敖之六卒,將中軍,曰,今日必無晉矣,子西將左,子上將右;

On the Chu side, Dechen, with the 600 men of the Ruo'ao family, was acting as commander of the central army. "Today, mark my word, Jin will be wiped out!" he said. Dou Yishen was acting as commander of the left wing of the Chu army, and Dou Bo as commander of the right wing.

胥臣蒙馬以虎皮,先犯陳蔡,陳蔡奔,楚右師潰;

Xu Chen, having cloaked his horses in tiger skins, led the attack by striking directly at the troops of Chen and Cai. The men of Chen and Cai fled, and the right wing of the Chu army was thus routed.

狐毛設二旆而退之,欒枝使輿曳柴而偽遁,楚師馳之,原軫,郤溱,以中軍公族橫擊之,狐毛,狐偃,以上軍夾攻子西,楚左師潰,楚師敗績,子玉收其卒而止,故不敗。

Hu Mao [the commander of the Jin upper army] hoisted two pennons and began to retreat, while Luan Zhi [the commander of the Jin lower army] had his men drag brushwood over the ground to simulate the dust of a general rout. The Chu forces raced after in pursuit, whereupon Yuan Chen and Xi Chen, leading the duke's own select troops of the central army, fell upon them from either side. Hu Mao and Hu Yan, leading the upper army, turned about and likewise attacked Dou Yishen from either side, thereby routing the left wing of the Chu army. Thus the Chu army suffered a resounding defeat. Only Dechen, who had kept his troops back and had not attempted to pursue the enemy, as a result managed to escape defeat.

The narrative of the Battle of Chengpu is typical of Zuo zhuan battle narratives: the description of the battle itself is relatively brief, with most of the narrative being focused on battle preparations, omens and prognostications regarding its outcome, the division of the spoils, and the shifts and defections of the various allied states involved in the conflict.[24] This "official [and] restrained" style, which became typical of Chinese historical writing, is largely due to the ancient Chinese belief that ritual propriety and strategic preparation were more important than individual valor or bravery in determining the outcome of battles.[23]

Succession crises

Several of the most notable passages in the Zuo zhuan describe succession crises, which seem to have been fairly common in China during the Spring and Autumn period.[23] These crises often involved the "tangled affections" of the various rulers, and are described in a dramatic and vivid manner that gives insight into the life of the aristocratic elite in the China of the mid-1st millennium BC.[23] The best known of these stories is that of Duke Zhuang of Zheng, who ruled the State of Zheng from 743 to 701 BC.[23] Duke Zhuang was born "in a manner that startled" his mother (probably breech birth), which caused her to later seek to persuade her husband to name Duke Zhuang's younger brother as the heir apparent instead of him.[23] The story ends with eventual reconciliation between mother and son, thus exemplifying the traditional Chinese virtues of both "ritual propriety" (lǐ) and "filial piety" (xiào 孝), which has made it consistently popular with readers over the centuries.[23]

Moral verdicts

A number of Zuo zhuan anecdotes end with brief moral comments or verdicts that are attributed to either Confucius or an unnamed junzi (君子; "gentleman", "lordling", or "superior man").[26]

君子謂是盟也信,謂晉於是役也,能以德攻。

The gentleman remarks: This alliance accorded with good faith. In this campaign, the ruler of Jin [Chong'er] was able to attack through the power of virtue.

These "moral of the story" postfaces, which were added later by Confucian scholars, are directed toward those currently in power, reminding them of "the historical precedents and inevitable consequences of their own actions."[26] They speak with the voices of previous ministers, advisers, "old men", and other anonymous figures to remind rulers of historical and moral lessons, and suggest that rulers who heed their advice will succeed, while those who do not will fail.[28]

Fate

Several sections of the Zuo zhuan demonstrate the traditional Chinese concept of "fate" or "destiny" (mìng 命), referring either to an individual's mission in life or their allotted lifespan, and illustrates how benevolent rulers ought to accept "fate" selflessly, as in the story of Duke Wen moving the capital of the state of Zhu in 614 BC.[29]

邾文公卜遷于繹,史曰,利於民而不利於君。邾子曰,苟利於民,孤之利也,天生民而樹之君,以利之也,民既利矣,孤必與焉;

Duke Wen of Zhu divined by turtle shell to determine if he should move his capital to the city of Yi. The historian who conducted the divination replied, "The move will benefit the people but not their ruler." The ruler of Zhu said, "If it benefits the people, it benefits me. Heaven gave birth to the people and set up a ruler in order to benefit them. If the people enjoy the benefit, I am bound to share in it."

左右曰,命可長也,君何弗為。邾子曰,命在養民,死之短長,時也,民苟利矣,遷也,吉莫如之;

Those around the ruler said, "If by taking warning from the divination you can prolong your destiny, why not do so?" The ruler replied, "My destiny lies in nourishing the people. Whether death comes to me early or late is merely a matter of time. If the people will benefit thereby, then nothing could be more auspicious than to move the capital."

遂遷于繹。五月,邾文公卒。

In the end he moved the capital to Yi. In the fifth month Duke Wen of Zhu died.

君子曰,知命。

The noble person remarks: He understood the meaning of destiny.

Influence

The Zuo zhuan has been recognized as a masterpiece of early Chinese prose and "grand historical narrative" for many centuries.[15] It has had an immense influence on Chinese literature and historiography for nearly 2000 years,[30] and was the primary text by which historical Chinese readers gained an understanding of China's ancient history.[4] It enjoyed high status and esteem throughout the centuries of Chinese history because of its great literary quality, and was often read and memorized because of its role as the preeminent expansion and commentary on the Annals (Chunqiu), which almost all Chinese traditionally ascribed to Confucius.[31] It was commonly believed throughout much of Chinese history that the terse, succinct entries of the Annals contained cryptic references to Confucius' "profound moral judgments on the events of the past as well as those of his own day and on the relation of human events to those in the natural order", and that the Zuo zhuan was written to clarify or even "decode" these hidden judgments.[32]

From the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) down to the present day, the Zuo zhuan has been viewed as a model of correct, elegant, and sophisticated Classical Chinese prose.[33] The Zuo zhuan's great influence on the Chinese language—particularly on Classical Chinese—is evident from the fact that it is the source of more Chinese literary idioms (chéngyǔ 成語) than any other work, including the Analects of Confucius.[34] The well-known Qing dynasty student anthology Guwen Guanzhi included 34 passages from the Zuo zhuan as paragons of Classical Chinese prose – more than any other source. These passages are still part of the Classical Chinese curriculum in mainland China and Taiwan today.

The 400-year period the Zuo zhuan covers is now known as the Spring and Autumn period, after the Spring and Autumn Annals, but the Zuo zhuan is the most important source for the period.[35] This era was highly significant in Chinese history, and saw a number of developments in governmental complexity and specialization that preceded China's imperial unification in 221 BC by the First Emperor of Qin.[30] The latter years of this period also saw the appearance of Confucius, who later became the preeminent figure in Chinese cultural history.[30] The Zuo zhuan is one of the only surviving written sources for the history of the Spring and Autumn period, and is extremely valuable as a rich source of information on the society that Confucius and his disciples lived in and from which the Confucian school of thought developed.[30] It was canonized as one of the Chinese classics in the 1st century AD, and until modern times was one of the cornerstones of traditional education for men in China and the other lands of the Sinosphere such as Japan and Korea.[30]

Translations

- James Legge (1872), The Ch'un Ts'ew, with the Tso Chuen, The Chinese Classics V, London: Trübner, Part 1 (books 1–8), Part 2 (books 9–12). Revised edition (1893), London: Oxford University Press.

- (in French) Séraphin Couvreur (1914), Tch'ouen Ts'iou et Tso Tchouan, La Chronique de la Principauté de Lou [Chunqiu and Zuo zhuan, Chronicle of the State of Lu], Ho Kien Fou: Mission Catholique.

- (in Japanese) Teruo Takeuchi 竹内照夫 (1974–75). Shunjū Sashiden 春秋左氏伝 [Chunqiu Zuoshi zhuan]. Zenshaku kanbun taikei 全釈漢文体系 [Fully Interpreted Chinese Literature Series] 4–6. Tokyo: Shūeisha.

- Burton Watson (1989). The Tso chuan: Selections from China's Oldest Narrative History. New York: Columbia University Press.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) Reprinted (1992).

- Hu Zhihui 胡志挥; Chen Kejiong 陈克炯 (1996). Zuo zhuan 左传. Changsha: Hunan renmin chubanshe. (Contains both English and Mandarin translations)

- Stephen Durrant; Li Wai-yee; David Schaberg, trans. (2016), Zuo Tradition (Zuozhuan), Seattle: University of Washington Press.

References

Citations

- Durrant, Li & Schaberg (2016), p. xxxviii.

- Durrant, Li & Schaberg (2016), p. xxxix.

- Cheng (1993), p. 72.

- Goldin (2001), p. 93.

- Idema & Haft (1997), p. 78.

- Shih (2014), p. 2394.

- Durrant, Li & Schaberg (2016), p. xx.

- Cheng (1993), p. 69.

- Kern (2010), p. 48.

- Watson (1989), p. xiii.

- Li (2007), p. 54.

- Cheng (1993), pp. 69-70.

- Shih (2014), p. 2395.

- Cheng (1993), p. 70.

- Kern (2010), p. 49.

- Cheng (1993), pp. 72-73.

- Wang (1986), p. 804.

- Durrant (2001), p. 497.

- Durrant, Li & Schaberg (2016), pp. 218–21.

- Owen (1996), p. 77.

- Wang (1986), p. 805.

- Watson (1989), p. xviii-xix.

- Durrant (2001), p. 499.

- Watson (1989), p. 50.

- Watson (1989), pp. 60-61.

- Kern (2010), p. 50.

- Watson (1989), p. 63.

- Kern (2010), pp. 50–51.

- Watson (1999), p. 189.

- Watson (1989), p. xi.

- Durrant (2001), p. 500.

- Watson (1999), p. 184.

- Boltz (1999), p. 90.

- Wilkinson (2015), p. 612.

- Hsu (1999), p. 547.

Works cited

- Boltz, William G. (1999). "Language and Writing". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–123. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

- Cheng, Anne (1993). "Chun ch'iu 春秋, Kung yang 公羊, Ku liang 穀梁, and Tso chuan 左傳". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California Berkeley. pp. 67–76. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Durrant, Stephen (2001). "The Literary Features of Historical Writing". In Mair, Victor H. (ed.). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 493–510. ISBN 0-231-10984-9.

- Durrant, Stephen; Li, Wai-yee; Schaberg, David (2016). Zuo Tradition (Zuozhuan): Commentary on the "Spring and Autumn Annals". Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295999159.

- Goldin, Paul R. (2001). "The Thirteen Classics". In Mair, Victor H. (ed.). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 86–96. ISBN 0-231-10984-9.

- Hsu, Cho-yun (1999). "The Spring and Autumn Period". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 545–86. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

- Idema, Wilt; Haft, Lloyd (1997). A Guide to Chinese Literature. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 0-89264-099-5.

- Kern, Martin (2010). "Early Chinese literature, Beginnings through Western Han". In Owen, Stephen (ed.). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 1: To 1375. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–115. ISBN 978-0-521-11677-0.

- Li, Wai-yee (2007). The Readability of the Past in Early Chinese Historiography. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-01777-1.

- Owen, Stephen (1996). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03823-8.

- Shih, Hsiang-lin (2014). "Zuo zhuan 左傳". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part Four. Leiden: Brill. pp. 2394–99. ISBN 978-90-04-27217-0.

- Wang, John C. Y. (1986). "Tso-chuan 左傳". In Nienhauser, William H. (ed.). The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 804–6. ISBN 0-253-32983-3.

- Watson, Burton (1989). The Tso chuan: Selections from China's Oldest Narrative History. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-06714-3.

- Watson, Burton (1999). "The Evolution of the Confucian Tradition in Antiquity — The Zuozhuan". In de Bary, Wm. Theodore; Bloom, Irene (eds.). Sources of Chinese Tradition, Vol. 1: From Earliest Times to 1600 (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 183–89. ISBN 978-0-231-10939-0.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual (4th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-08846-7.

Further reading

- Yang Bojun (1990). Chunqiu Zuozhuan zhu 春秋左传注 [Annotated Chunqiu Zuozhuan]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. ISBN 7-101-00262-5.

External links

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Chunqiu Zuozhuan Bilingual text of Zuo zhuan with side-by-side Chinese original and Legge's English translation

- Zuo zhuan Fully searchable text (Chinese)

- Zuo zhuan with annotations by Yang Bojun

- The Commentary of Zuo on the Spring and Autumn Annals 《春秋左氏傳》 Chinese text with matching English vocabulary at chinesenotes.com